Pharyngeal Procedures

Eva Vogeley

Richard A. Saladino

Introduction

Three pharyngeal problems in children that may be treated in the emergency department (ED)—pharyngitis, tonsillar foreign body, and peritonsillar abscess—require careful and complete historical investigation and physical examination before any diagnostic or ameliorative procedure is initiated.

Pharyngitis is one of the more common reasons for which children and adolescents seek emergency care. Pharyngitis may manifest in several different clinical ways, including nasopharyngitis, tonsillopharyngitis, and tonsillitis. It is essential that diagnostic procedures are used that may enable the clinician to distinguish between viral and bacterial causes of pharyngitis. Treatment of viral pharyngitis with antibiotics is unnecessary and may result in an allergic response to the antibiotic and development of antibiotic resistance in the community. Failure to identify and treat group A streptococcal pharyngitis may lead to complications such as peritonsillar and retropharyngeal abscess and rheumatic fever (1,2).

Foreign body ingestion is not an uncommon problem in both the pediatric and adult age groups. However, tonsillar foreign body is an infrequent finding, although in older children and adolescents it is no less common than in the adult population. Jones et al. described 388 patients aged 0 to 90 years in whom 60 of 121 foreign bodies retained in the throat were located in the tonsil and 67 of 71 fishbones were found in the tonsil or posterior third of the tongue (3). Management of a tonsillar foreign body depends on the particular foreign body and its location, but it is often a straightforward procedure performed by the emergency physician.

Peritonsillar abscess (quinsy), one of the most common abscesses of the head and neck, is thought to be rare in children younger than 8 years but has been reported in children only 4 months (4) and 15 months (5) of age. In fact, in one study of children with peritonsillar abscess, 31% of patients were younger than 10 years of age (6), whereas in another, the mean age was 10 years (range, 3 to 16 years) (7). Management of peritonsillar abscess has undergone considerable and controversial change over the last century. Management options include medical (antibiotic) treatment, transmucosal needle aspiration, incision and drainage, acute tonsillectomy, and delayed tonsillectomy (8,9,10,11). The emergency physician is involved in medical treatment and, in selected cases, may perform needle aspiration or incision and drainage prior to or instead of admission to the hospital. When available, consultation with an otolaryngologist should be sought in such cases.

Anatomy and Physiology

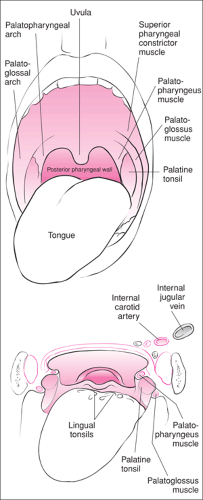

The palatine tonsils—the lateral component of the Waldeyer ring of lymphatic tissue (composed of the palatine, lingual, and pharyngeal tonsils)—lie in the tonsillar fossa (Fig. 60.1) (12). The deep or lateral surface of the palatine tonsil is a fibrous connective tissue capsule that opposes the superior constrictor muscle; the palatopharyngeal muscle lies posteriorly and the palatoglossal muscle lies rostral (13,14). Importantly, the tonsillar and ascending palatine branches of the facial artery are just lateral to the constrictor muscle, whereas the internal carotid artery is no more than 2 cm dorsal and lateral.

Pharyngitis

Primary bacterial pathogens account for approximately 30% of cases of pharyngitis in children, the most common being Streptococcus pyogenes and group A β-hemolytic streptococci. Less common causes include group G streptococci and Neisseria gonorrhoea (cultured from sexually active adolescents and

as a coincident infection in some young victims of sexual abuse). Fortunately, widespread childhood immunization has made Corynebacterium diphtheriae very uncommon. Most bacterial pharyngitis requires antibiotic treatment. Common viral causes include adenovirus, influenza virus, rhinovirus, and parainfluenza virus. Coxsackievirus and herpes simplex virus may cause pharyngitis marked by the presence of vesicles. Ebstein-Barr virus (infectious mononucleosis) causes pharyngitis primarily in older children and adolescents. The atypical organisms Chlamydia trachomatis and Mycoplasma pneumoniae are less common causes of childhood pharyngitis.

as a coincident infection in some young victims of sexual abuse). Fortunately, widespread childhood immunization has made Corynebacterium diphtheriae very uncommon. Most bacterial pharyngitis requires antibiotic treatment. Common viral causes include adenovirus, influenza virus, rhinovirus, and parainfluenza virus. Coxsackievirus and herpes simplex virus may cause pharyngitis marked by the presence of vesicles. Ebstein-Barr virus (infectious mononucleosis) causes pharyngitis primarily in older children and adolescents. The atypical organisms Chlamydia trachomatis and Mycoplasma pneumoniae are less common causes of childhood pharyngitis.

Tonsillar Foreign Body

Up to 12% of foreign bodies found in the aerodigestive tract of children are fish or chicken bones (13). Although the majority of objects that children swallow are not retained in the throat, foreign bodies with a spicular shape may be become lodged in the tonsil. These include fish bones, meat bones, and hard seed husks as well as man-made objects such as glass, plastic toothbrush bristles, straight and safety pins, ballpoint pen caps, and countless other spicate household items that arouse the curiosity of children (14,15,16,17).

Peritonsillar Abscess

Peritonsillar abscess is the most common complication of tonsillitis (6,21) and is a result of suppurative infection of the tonsil. This infection penetrates the tonsillar capsule and extends into the connective tissue space between the fibrous wall of the capsule and the posterior wall of the tonsillar fossa overlying the superior constrictor muscle. Localized purulent material (pus) extends superiorly into the soft palate. Although 85% to 90% of abscesses occur in the superior pole of the tonsillar space, pus can accumulate in the midaspect or lower pole (9,21,22). Peritonsillar abscesses are almost always unilateral (22,23). Further dissection of the infected space may result in the extension of organisms through the constrictor muscle and in deep neck infection if a peritonsillar abscess remains untreated.

The microbiology of peritonsillar abscess cultures is polymicrobial in 30% to 75% of aspirates, with S. pyogenes being one of the primary pathogens (7,24). In several recent series of pediatric patients, S. pyogenes was isolated in 25% to 30% of aspirate cultures, other Streptococcus species in 20% to 40%, and anaerobic pathogens in 12% to 33% (6,7,9). In two of these studies, 30% of aspirate cultures yielded both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria such as Streptococcus and Bacteroides species (6,9). Interestingly, 20% to 35% of abscess cultures will not grow bacterial pathogens (6,7,9,25).

Indications

Pharyngitis

Except for patients with a classical scarlatiniform rash, streptococcal pharyngitis cannot be reliably diagnosed based on clinical grounds. The presence of sore throat, enlarged tonsils, palatal petechiae, and anterior cervical adenopathy in the absence of symptoms of a viral upper respiratory infection warrant obtaining a diagnostic test for group A β-hemolytic streptococci. In children under 2 years of age, these typical symptoms may be absent, and therefore testing for group A β-hemolytic streptococci may be indicated in this population despite a paucity of findings when there is an exposure history.

Tonsillar Foreign Body

Older patients with tonsillar foreign bodies will report swallowing a foreign body or choking on food with spicular bones or fragments. Most will have sudden onset of discomfort, and as many as 68% of patients who localize their pain to the tonsil have been found to have foreign bodies (3). Otalgia is not uncommon, and odynophagia can progressively worsen. However, it should be noted that foreign body sensation is not reliably reported (13). Younger (especially preverbal) children may have subtle presentations, such as an unwitnessed or unexplained choking episode during a meal or while playing with small objects. Children with developmental delay are at higher risk for foreign body ingestion, with late presentation not uncommon (3,13).

Careful inspection of the tonsillar fossae and palate will detect most tonsillar foreign bodies. Using an indirect mirror or fiberoptic nasopharyngoscopy will lead to a more effective examination when the foreign body cannot be adequately or fully visualized (see Chapter 61). Radiographs will corroborate clinical findings of radiopaque foreign bodies such as meat and poultry bones, pins, and most glass. Of note, not all fish species bones are radiographically visible. Ell and Sprigg assessed the radiopacity of the bones of 14 species of fish in a swine head and neck preparation. On plain radiograph, bones of the cod, gurnard, haddock, cole fish, lemon sole, monk fish, and red snapper were moderately or clearly visible in the tonsil, larynx, vallecula, and esophagus (Fig. 60.2). In contrast, bones of the salmon, trout, pike, mackerel, herring, and plaice were not radiopaque (26).

The uncooperative patient or young child with a tonsillar foreign body should be examined carefully by both the emergency physician and a consulting otolaryngologist. Removing a foreign body in such a patient may require general anesthesia in the operating room. For the older and cooperative patient, removal is usually straightforward if the site and depth of the foreign body is established. A lateral radiograph of the soft tissues of the neck can be helpful before removal.

Contraindications for removal of a tonsillar foreign body in the ED include an uncooperative or young child, difficulty visualizing the appropriate anatomy or the foreign body, and anticipation of a difficult removal or difficult management of the airway.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree