Approximately 0.5% of all births occur before the third trimester of pregnancy, and these very early deliveries result in the majority of neonatal deaths and more than 40% of infant deaths. A recent executive summary of proceedings from a joint workshop defined periviable birth as delivery occurring from 20 0/7 weeks to 25 6/7 weeks of gestation. When delivery is anticipated near the limit of viability, families and health care teams are faced with complex and ethically challenging decisions. Multiple factors have been found to be associated with short-term and long-term outcomes of periviable births in addition to gestational age at birth. These include, but are not limited to, nonmodifiable factors (eg, fetal sex, weight, plurality), potentially modifiable antepartum and intrapartum factors (eg, location of delivery, intent to intervene by cesarean delivery or induction for delivery, administration of antenatal corticosteroids and magnesium sulfate), and postnatal management (eg, starting or withholding and continuing or withdrawing intensive care after birth). Antepartum and intrapartum management options vary depending upon the specific circumstances but may include short-term tocolytic therapy for preterm labor to allow time for administration of antenatal steroids, antibiotics to prolong latency after preterm premature rupture of membranes or for intrapartum group B streptococci prophylaxis, and delivery, including cesarean delivery, for concern regarding fetal well-being or fetal malpresentation. Whenever possible, periviable births for which maternal or neonatal intervention is planned should occur in centers that offer expertise in maternal and neonatal care and the needed infrastructure, including intensive care units, to support such services. This document describes newborn outcomes after periviable birth, provides current evidence and recommendations regarding interventions in this setting, and provides an outline for family counseling with the goal of incorporating informed patient preferences. Its intent is to provide support and guidance regarding decisions, including declining and accepting interventions and therapies, based on individual circumstances and patient values.

(Replaces Obstetric Care Consensus Number 3, November 2015)

INTERIM UPDATE: This Obstetric Care Consensus is updated to reflect a limited, focused change in the description and presentation of data regarding the percentage of survival with moderate or severe impairment among surviving newborns.

The information reflects emerging clinical and scientific advances as of the date issued, is subject to change, and should not be construed as dictating an exclusive course of treatment or procedure. Variations in practice may be warranted based on the needs of the individual patient, resources, and limitations unique to the institution or type of practice.

Approximately 0.5% of all births occur before the third trimester of pregnancy, and these very early deliveries result in the majority of neonatal deaths and more than 40% of infant deaths. When delivery is anticipated near the limit of viability, families and health care teams are faced with complex and ethically challenging decisions. Decision making often needs to adapt to changing clinical circumstances before and after delivery. This document describes newborn outcomes after periviable birth, provides current evidence and recommendations regarding interventions in this setting, and provides an outline for family counseling with the goal of incorporating informed patient preferences. Its intent is to provide support and guidance regarding decisions, including both declining and accepting interventions and therapies, based on individual circumstances and patient values.

Background

What is considered the periviable period?

Numerous terms have been used to refer to newborns delivered near the limit of viability whose outcomes range from certain or near-certain death to likely survival with a high likelihood of serious morbidities. A recent executive summary of proceedings from a joint workshop sponsored by the Society for Maternal–Fetal Medicine, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), the Section on Perinatal Pediatrics of the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, in which a diverse group of experts were invited to participate, defined periviable birth as delivery occurring from 20 0/7 weeks to 25 6/7 weeks of gestation. (For consistency and clarity in this document, gestational age summarized in weeks of gestation refers to the completed week of gestation and the next 6 days; for example, “24 weeks of gestation” refers to 24 0/7 weeks through 24 6/7 weeks of gestation and “before 24 weeks of gestation” refers to before 24 0/7 weeks of gestation.)

What is the spectrum of outcomes for infants born in the periviable period?

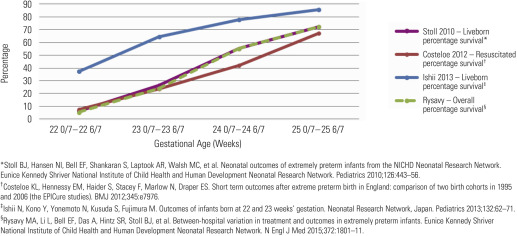

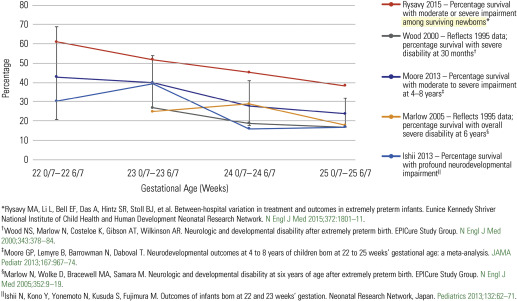

From the 1950s through 1980, newborn death was virtually assured with delivery of an infant, even one that was appropriately grown, at or before 24 weeks of gestation. It remains true in the present day that delivery before 23 weeks of gestation typically results in neonatal death (5–6% survival ), and among rare survivors, significant morbidity is universal (98–100% ). However, a recent study demonstrated that wide variation in practices exists regarding the initiation of resuscitation and active treatment at these very early gestational ages and that this variation explains some of the between-hospital differences in survival and survival without impairment, particularly at 22 weeks and 23 weeks. At more advanced gestational ages, however, practices and outcomes are more consistent across tertiary care institutions. A review of studies published over the past three decades reveals a progressive increase in the rate of survival for infants born at 22, 23, 24, and 25 weeks of gestation ( Figure 1 ). Data published for newborns delivered in the United States, England, and Australia within the past decade have indicated rates of survival to discharge of 23–27% for births at 23 weeks, 42–59% for births at 24 weeks, and 67–76% for births at 25 weeks of gestation. Long-term outcomes are summarized in Figure 2 . A follow-up study of a cohort of infants born at 22–26 weeks of gestation in England in 2006 found a progressive decrease in the proportion of children at age 30 months with severe or moderate impairment (defined as cerebral palsy, blindness, profound hearing loss, or developmental quotient 2 standard deviations or more below the mean) with increasing gestational age at birth: 45% at 22–23 weeks, 30% at 24 weeks, and 17% at 25 weeks of gestation. Similarly, a recent systematic review found that the incidence of moderate-to-severe neurodevelopmental impairment among survivors at 4–8 years decreased progressively with each week gained in gestational age at birth: 43% at 22 weeks, 40% at 23 weeks, 28% at 24 weeks, and 24% at 25 weeks of gestation ; notably, although the combined rate decreased, the rate of severe neurodevelopmental impairment alone did not decrease significantly with increasing gestational age in this study. It also should be emphasized that although summary data often are grouped into segments of weeks, outcomes for deliveries at the extreme may be closer to those of the adjacent week than to those at the other extreme of the same week (eg, outcomes at 23 6/7 weeks may be more similar to those at 24 0/7 weeks than to those at 23 0/7 weeks of gestation).

Clinical considerations and management

What tools are available to obstetrician–gynecologists, other obstetric providers, and families to predict outcomes of periviable birth?

Because of the wide range of outcomes associated with periviable birth, counseling should attempt to include accurate information that is as individualized as possible regarding anticipated short-term and long-term outcomes. Nevertheless, it is important to realize that outcomes that have been reported in the medical literature may have some biases because of a variety of factors, including study inclusion criteria (eg, whether studies include all births or are limited to liveborn infants, nonanomalous newborns, liveborn resuscitated newborns, or neonatal intensive care unit [NICU] admissions only), variation in management between centers, and changes in NICU practices over time (eg, administration of antepartum steroids, resuscitative efforts, NICU admission criteria; Table 1 ). In addition, a precise understanding of outcomes in survivors is further confounded by differing definitions of “major” and “minor” disabilities used in studies.

| Variable | Effect |

|---|---|

| Factors affecting reliability of estimates of probability of clinical outcomes | |

| Data source | International, national, regional, and single-institution data reflect variations in regional and local practices. |

| Cohort selection | Exclusion of newborns not surviving to NICU admission results in inclusion of those with higher potential for survival and higher reported rates of survival. Inclusion of nonresuscitated infants or stillbirths reduces overall reported rates of survival. Inclusion of anomalous infants may decrease reported survival estimates. |

| Gestational age assignment | In vitro fertilization and ovulation induction provide accurate gestational age assignment. Dating by last menstrual period assumes accurate recollection of this date as well as conception on day 14. Ultrasonography initially performed at less than 24 weeks of gestation estimates gestational age within 5 to 14 days. a |

| Factors potentially affecting clinical outcomes | |

| Nonmodifiable risk factors | Race and ethnicity, plurality (singleton versus multiple gestation), infant sex, birthweight, gestational age |

| Modifiable obstetric practices | Antenatal interventions (eg, corticosteroids, tocolysis, antibiotics for preterm PROM, or magnesium for neuroprotection), site and mode of delivery |

| Modifiable neonatal practices | Initial resuscitation and subsequent care (eg, approaches to ventilation and oxygenation, nutritional support, and treatment of newborn infections) |

| Approaches to comfort care | Influenced by institutional and physician philosophies, parental wishes, and religious convictions |

| Regional/hospital legal and practice guidelines | Policies concerning neonatal resuscitation |

a Method for estimating due date, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Multiple factors have been found to be associated with short-term and long-term outcomes of periviable births in addition to gestational age at birth ( Table 1 ). These include, but are not limited to, nonmodifiable factors (eg, fetal sex, weight, plurality), potentially modifiable antepartum and intrapartum factors (eg, location of delivery, intent to intervene by cesarean delivery or induction of labor, administration of antenatal corticosteroids and magnesium sulfate), and life-sustaining interventions and postnatal management (eg, starting or withholding and continuing or withdrawing intensive care after birth).

Birthweight and gestational age, alone or in combination, often have been used as predictors of outcome and as criteria for offering resuscitation. However, in recognition of the effect of other clinical factors and in an attempt to create a better prediction tool, the NICHD Neonatal Research Network developed a tool to estimate outcomes among liveborn infants that was based on prospectively collected information for live births at 22–25 weeks of gestation in 19 academic NICU centers (available at https://neonatal.rti.org ). The estimated outcomes are probabilities derived from data obtained from 4446 infants born at 400–1000 g without major congenital anomalies who were admitted to a level III or IV Neonatal Research Network hospital between 1998 and 2003 and monitored until 18–22 months’ corrected age. Using these data, the combination of 5 variables—(1) gestational age, (2) birthweight, (3) exposure to antenatal corticosteroids, (4) sex, and (5) plurality—was found to be more predictive of outcomes than gestational age and birth weight alone. The NICHD estimator estimates frequencies of outcomes for all live births and for resuscitated newborns receiving mechanical ventilation. In addition to NICHD data and estimates, other organizations may have access to data from their own networks that can be useful for counseling, and they should be encouraged to use available contemporary data to develop and evaluate alternative prediction tools. After delivery, a number of initial illness severity scoring systems have been used in newborn care to predict death or adverse neurologic outcomes.

What are the limitations of these tools and how should this information be incorporated into family counseling?

Prediction models for estimating neonatal outcomes after periviable birth were developed based on populations of neonates born during a given period, but as medical care advances, these models (if not updated based on more recent information) may not provide estimates with an accuracy equivalent to that initially reported. Prediction of outcome frequencies based on gestational age, birthweight, or both in combination with other predictors provides only a point estimate reflecting a population average and cannot predict with certainty the outcome for an individual newborn. Further, gestational age is a key component of any predictive model and may not be known accurately in all cases. Also, defining outcomes based on completed weeks arbitrarily eliminates the differences between a fetus at 23 0/7 weeks and one at 23 6/7 weeks of gestation as well as the similarities between a fetus at 23 6/7 weeks and one at 24 0/7 weeks of gestation. Furthermore, before delivery, newborn birthweight can only be estimated. The inherent inaccuracy of ultrasound-estimated fetal weight introduces a degree of uncertainty to the prediction of newborn outcomes. In addition, how parents weigh and value these potential outcomes (ie, death, degree of neurodevelopmental impairment) can vary widely, and individual values need to be incorporated into decision making. Finally, the response of an individual neonate to resuscitation can never be known with certainty before delivery. Thus, when a specific estimated probability for an outcome is offered, it should be stated clearly that this is an estimate for a population and not a prediction of a certain outcome for a particular patient in a given institution. It is not known if and how the use of these tools improves care, patient-centered outcomes, or families’ satisfaction with decision making. These limitations highlight the need for further research and development of improved prediction models and counseling tools. However, at present, the NICHD estimator (available at www.nichd.nih.gov/about/org/der/branches/ppb/programs/epbo/Pages/epbo_case.aspx?start=13:15:46 ) remains the most widely available resource to estimate the likelihood of perinatal morbidity and mortality.

What are the considerations of periviable delivery for maternal health?

The effect of periviable delivery on maternal health is an important consideration that should be incorporated into counseling. In the setting of possible periviable birth, interventions intended to delay delivery or to improve newborn outcomes often are undertaken but may affect maternal outcomes. Although some interventions (eg, antenatal corticosteroid administration or magnesium sulfate for neuroprotection) pose relatively low risk to the pregnant woman and offer the prospect of a fetal benefit, others (eg, emergent cerclage placement or classical cesarean delivery) may result in significant short-term and long-term maternal morbidity. Risks to a pregnant woman’s short-term and long-term health need to be evaluated in the context of a newborn’s predicted outcome and the degree to which the intervention in question is predicted to improve this outcome. Although maternal risks associated with individual interventions may not vary widely with a neonate’s gestational age, expectations for anticipated benefit to neonatal outcome may more strongly support undertaking such risks at later gestational ages.

Because preterm birth frequently is associated with fetal malpresentation, whether to undertake a cesarean delivery for malpresentation is a relatively common question related to periviable gestation. Earlier cesarean delivery is associated with a higher likelihood that the needed hysterotomy will be a vertical uterine incision (classical hysterotomy) extending into the upper muscular portion of the uterus. Hysterotomy that involves the muscular portion of the uterus has been associated with more frequent perioperative morbidities than low transverse cesarean delivery and also leads to the recommendation for repeat cesarean delivery in future pregnancies because of the increased risk of uterine rupture with labor. In addition, recent data indicate that regardless of incision type, periviable cesarean delivery results in an increased risk of uterine rupture in a subsequent pregnancy. Finally, cesarean delivery is associated with future reproductive risks, which increase further with each additional repeat cesarean delivery.

Maternal morbidity and mortality may arise not just with interventions surrounding periviable pregnancy management but also with decisions not to intervene. For example, decisions to delay delivery (so-called “expectant management”) in the setting of preterm premature rupture of membranes (PROM) may result in maternal infection or, in the setting of severe preeclampsia, may result in hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count (HELLP) syndrome or other complications of worsening preeclampsia. These examples emphasize that patients, obstetrician–gynecologists, and other obstetric providers should together consider such risks in the context of the parents’ goals of care (resuscitative compared with palliative); the potential for newborn survival with immediate delivery; the likelihood of extended latency to improve newborn outcomes; and the likelihood of severe adverse maternal outcomes with attempted pregnancy prolongation, individual interventions proposed for fetal or neonatal benefit, or both.

What obstetric and pediatric resources should be available in institutions that provide care for periviable birth? When should transport occur, if needed?

Periviable infants do not survive without life-sustaining interventions immediately after delivery. The circumstances prompting periviable birth are, in many cases (eg, preeclampsia with severe features), also likely to require advanced care and resources to improve a woman’s outcome. Delivery of a pregnancy in the periviable period at a center with a level III–IV NICU, level III–IV maternal care designation, or both, allows for immediate resuscitation with additional needed ancillary supports (eg, respiratory technology, newborn imaging 24 hours daily) and advanced maternal care to optimize outcomes for the neonate and woman.

Accordingly, whenever possible, periviable births for which maternal or neonatal intervention is planned should occur in centers that offer expertise in maternal and neonatal care and the needed infrastructure, including intensive care units, to support such services. Efforts should be made to transfer women before delivery, if feasible, because antenatal transfer has been associated with improved neonatal outcome when compared with transport of a neonate after delivery. It similarly stands to reason that transfer of a parturient for advanced care before her condition worsens may improve her outcome as well.

To facilitate needed transfers, hospitals without the optimal resources for maternal, fetal, and neonatal care needed for periviable birth should have policies and procedures in place to facilitate timely transport to a receiving hospital. Protocols with guidelines for the initial management and safe transport of the periviable gestation should include recommendations for such treatments as antenatal corticosteroids, magnesium sulfate for neuroprotection, tocolytic therapy, antibiotics for latency after preterm PROM, and group B streptococci prophylaxis.

In some cases, circumstances may preclude antenatal maternal transport because of a rapidly evolving clinical situation or because of maternal instability due to severe illness. In such cases, neonatal transport after delivery may be needed, and protocols also should be in place to facilitate postpartum consultation and transfer. Final decisions regarding interventions to be initiated before transfer, as well as the optimal timing and method of transport, should be individualized and made in consultation with the accepting physician.

What are the benefits and risks of obstetric interventions for anticipated or inevitable periviable birth?

As in any pregnancy, obstetric interventions should be undertaken only after a discussion with the family regarding individual risks and benefits of management options in addition to alternate approaches. In order to facilitate informed decision making, this discussion should include an unbiased presentation of data related to the chance of both survival and long-term neurodevelopmental impairment. This discussion also should present the option of nonintervention. In light of the high likelihood of death and the significant degree of neurodevelopmental impairment that may result from periviable birth, the American Academy of Pediatrics has stated that parents should be given the choice for palliative care alongside the option to attempt resuscitation. Clinicians should recognize that parental goals of care may be oriented toward optimizing survival or minimizing pain and suffering and should formulate an antenatal plan of care in accordance with these parental goals. Rather than treat patients based upon algorithms organized solely by gestational age, a plan of care should be informed primarily by whether the goal is to optimize the chance of survival or minimize the likelihood of suffering.

Given the potential for maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality, the option of pregnancy termination should be reviewed with the patient. Individual obstetrician–gynecologists and other obstetric providers or institutions may have objections to discussing or providing this option, but in the case of such objections, there should be a system in place to allow families to receive counseling about their options and access to such care. The management plan for ongoing pregnancies should be reassessed and follow-up counseling should be provided as the clinical situation develops and gestational age increases. Initiation of interventions to help improve outcome (eg, administration of antenatal antibiotics or corticosteroids) does not mandate that all other interventions (eg, cesarean delivery or newborn resuscitation) subsequently be undertaken. Further interventions should be considered in the context of clinical circumstances at that time. Accurate pregnancy dating is of particular importance in the periviable period, and the best estimate of gestational age should be used for counseling and decision making.

Obstetric interventions often considered in pregnancies at risk of periviable delivery include treatments to delay delivery as well as efforts to improve newborn outcomes should delivery occur despite such efforts. Treatment options vary depending upon the specific circumstances but may include short-term tocolytic therapy for preterm labor to allow additional time for administration of antenatal steroids, emergent cerclage, antibiotics to prolong latency after preterm PROM or for intrapartum group B streptococci prophylaxis, and delivery (including cesarean delivery) for concern regarding fetal well-being or fetal malpresentation.

Data regarding the use of obstetric interventions during the periviable period, especially for gestational ages less than 24 weeks, however, are limited, as these gestational ages were not included in many studies, especially those performed in the 1970s and 1980s. Even the studies that included subjects in the periviable gestational age range typically had small numbers in these groups, with corresponding limited power to evaluate the effect of interventions. As a result, most recommendations for management in the periviable gestational age range are extrapolated from data available for women who gave birth between 26 weeks and 34 weeks of gestation.

Guidance offered in this document for the management of the pregnancy at risk of periviable birth is based, therefore, on a mix of direct evidence, data extrapolated from more advanced gestational ages, and expert opinion. This guidance, summarized in Tables 2 and 3 and Appendix , is considered in more detail below. There are a few perspectives that serve to frame these recommendations:

- •

Recommendations presented in this document vary in some aspects from those published and summarized previously in part because of further stratification of advice offered for anticipated deliveries between 23 0/7 weeks and 25 6/7 weeks of gestation. Outcomes vary widely across this gestational age range, as do the quantity and quality of available data supporting various proposed interventions. The recommendations are intended to provide guidance that will facilitate implementation of the 2014 NICHD workshop recommendations.

- •

In formulating a plan of care for periviable neonates, clinicians should discuss with parents whether their goal is optimizing survival or minimizing suffering. The approach to antenatal and postdelivery care may differ dramatically depending on parental preferences regarding resuscitation.

- •

A recommendation regarding assessment for resuscitation is not meant to indicate that resuscitation should always either be undertaken or deferred, or that every possible intervention need be offered. A stepwise approach concordant with neonatal circumstances and condition and with parental wishes is appropriate. Care should be reevaluated regularly and potentially redirected based on the evolution of the clinical situation. Assessment at birth, for example, may include confirmation that comfort measures are most appropriate.

- •

A decision to proceed with resuscitation always should be informed by individual circumstances, including specific clinical issues (especially, for example, estimated fetal weight and the most precise estimate of gestational age), family values and wishes, and ongoing evaluation of fetal or neonatal condition. In some cases, decisions will be informed by local institutional policy and relevant laws, of which obstetrician–gynecologists and other obstetric providers should be aware. Accordingly, the guidelines offer recommendations with regard to the gestational ages at which assessment for resuscitation rather than resuscitation itself should be undertaken. Such assessment is meant in most cases to refer to that provided by neonatologists or other pediatric providers, separate from that offered by obstetrician–gynecologists and other obstetric providers.

- •

A decision not to undertake resuscitation of a liveborn infant should not be seen as a decision to provide no care, but rather a decision to redirect care to comfort measures.

- •

Continuous electronic fetal heart rate monitoring is not separately considered as an intervention because in most cases its use will be linked to plans regarding cesarean delivery for fetal indications. Even if cesarean delivery for fetal indication is not planned, if arrangements have been made for resuscitation of a potentially viable liveborn neonate, electronic fetal heart rate monitoring may be considered if it is believed that intrauterine resuscitation will affect the newborn’s outcome.

- •

The less directive recommendation of “consider” is assigned to some guidance because of the very limited evidence regarding use of a given intervention in a particular gestational age range (because available evidence suggests limited benefit with significant potential risk) or if antenatal interventions will be altered by the intention to perform newborn resuscitation or to provide comfort care.

| Recommendations | Grade of Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Based on anticipated neonatal or maternal complications, antepartum transport to a center with advanced levels of neonatal or maternal care is recommended when feasible and appropriate. | Best practice |

| Prenatal and postnatal counseling regarding anticipated short-term and long-term neonatal outcome should take into consideration anticipated gestational age at delivery, as well as other variables that may alter the likelihood of survival and adverse newborn outcomes (eg, fetal sex, multiple gestation, the presence of suspected major fetal malformations, antenatal corticosteroid administration, birth weight, and response to initial newborn resuscitation). | Best practice |

| Family counseling should be provided by a multidisciplinary team that includes obstetrician–gynecologists and other obstetric providers, maternal–fetal medicine specialists, if available, and neonatologists who can address their individual and shared considerations and perspectives. Maternal and neonatal outcomes should be considered. Follow-up counseling should be provided when there is relevant new information about the maternal and fetal status or the newborn’s evolving condition. | Best practice |

| A predelivery plan, made with the parents, family, or both, should be recognized as a general plan of approach, which may be modified as the neonate’s condition and response is evaluated by the neonatal providers. A recommendation regarding assessment for resuscitation is not meant to indicate that resuscitation should always either be undertaken or deferred, or that every possible intervention need be offered. A stepwise approach concordant with neonatal circumstances and condition and with parental wishes is appropriate. Care should be reevaluated regularly and potentially redirected based on the evolution of the clinical situation. | Best practice |

| 20 0/7 weeks to 21 6/7 weeks | 22 0/7 weeks to 22 6/7 weeks | 23 0/7 weeks to 23 6/7 weeks | 24 0/7 weeks to 24 6/7 weeks | 25 0/7 weeks to 25 6/7 weeks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neonatal assessment for resuscitation a | Not recommended 1A | Consider 2B | Consider 2B | Recommended 1B | Recommended 1B |

| Antenatal corticosteroids | Not recommended 1A | Not recommended 1A | Consider 2B | Recommended 1B | Recommended 1B |

| Tocolysis for preterm labor to allow for antenatal corticosteroid administration | Not recommended 1A | Not recommended 1A | Consider 2B | Recommended 1B | Recommended 1B |

| Magnesium sulfate for neuroprotection | Not recommended 1A | Not recommended 1A | Consider 2B | Recommended 1B | Recommended 1B |

| Antibiotics to prolong latency during expectant management of preterm PROM if delivery is not considered imminent | Consider 2C | Consider 2C | Consider 2B | Recommended 1B | Recommended 1B |

| Intrapartum antibiotics for group B streptococci prophylaxis b | Not recommended 1A | Not recommended 1A | Consider 2B | Recommended 1B | Recommended 1B |

| Cesarean delivery for fetal indication c | Not recommended 1A | Not recommended 1A | Consider 2B | Consider 1B | Recommended 1B |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree