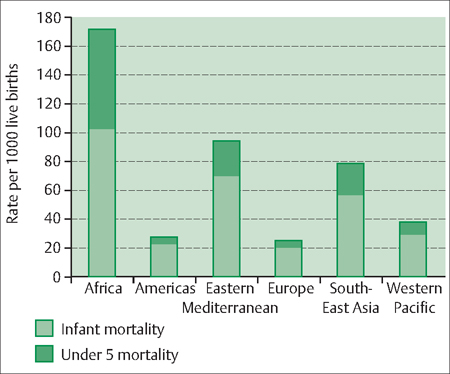

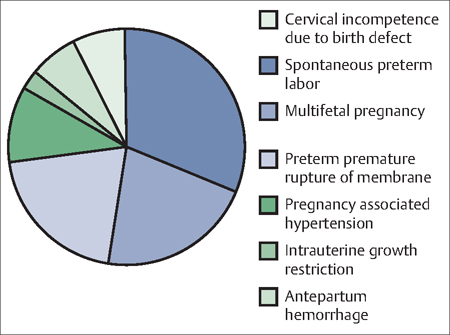

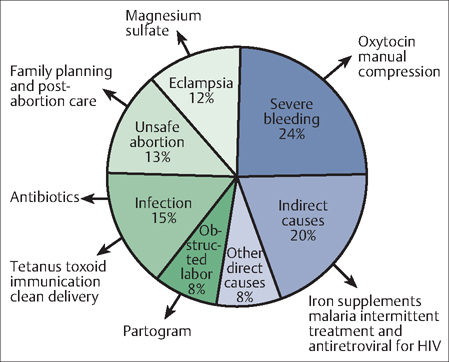

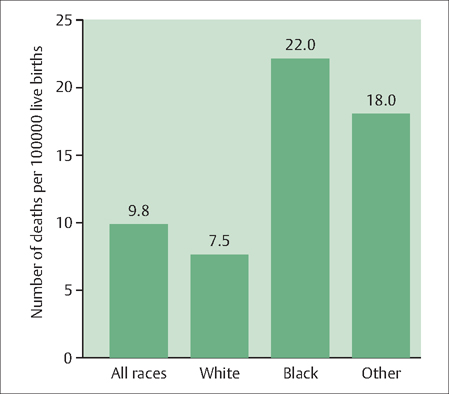

24 Perinatal and Maternal Mortality Eyal Sheiner and Arnon Wiznitzer Among the more than 130 million babies born worldwide every year, more than 10 million die before their ffth birthday; almost 8 million die before their first. In addition, an estimated half a million women die each year worldwide owing to pregnancy-related complications, most of them in the developing world. Millions of other women sustain serious health problems due to pregnancy and childbirth. Many of these deaths and illnesses are preventable. Clearly, the management and prevention of factors that increase women’s risk for perinatal mortality as well as their own mortality is an important public health concern globally. Other chapters in this book deal with approaches and protocols for preventing and managing specific conditions that increase the risks for perinatal and maternal mortality. The purpose of this chapter, therefore, is to define these phenomena and broadly outline their scope and strategies for dealing with them. Perinatal mortality: Perinatal mortality refers to deaths that occur in the period following birth of infants weighing at least 500 g or born after 20 completed weeks of gestation until they reach 28 completed days after birth. The perinatal mortality rate refers to the number of stillbirths and neonatal deaths per 1000 total births. If an infant dies during the first 7 days following birth, this is considered an early neonatal death. Death of a live-born infant after 7 days but before 29 days following birth is considered a late neonatal death. The term Infant death refers to deaths of live-born infants from birth until 1 year of age. Maternal mortality: Maternal mortality is maternal deaths that result from the reproductive process. The maternal mortality rate is the number of deaths per 100 000 live births (also known as the maternal mortality ratio). Maternal deaths: Deaths that result from an obstetric complication, treatment, or intervention during pregnancy, delivery, or the puerperium are considered direct maternal deaths. Maternal deaths that are not the direct result of the reproductive process, but rather are due to a previously existing conditions or a disease that developed during pregnancy and was aggravated by physiological adaptation to pregnancy, are considered indirect maternal deaths. Perinatal mortality is an important indicator of the level of health care provision in a society. Different definitions hamper direct comparisons between countries with regard to perinatal mortality rates. There has, however, been a dramatic decline in perinatal mortality rates in the Western world over the past several decades. In the United Kingdom, for example, there was a decline from 62 deaths per 1000 births to only 13 deaths per 1000 births during the 1990s. Mortality rates have declined in much of the developing world. However, perinatal mortality rates and those of children under 5 years of age are significantly higher in Africa and the Middle East compared with the Americas and Western Europe (Fig. 24.1). Premature birth (see Chapter 15) accounts for up to 70% of perinatal mortality cases in Western countries. There are many causes of premature birth, including infections, bleeding, and the stretching or overdistension of the uterus as a result of multiple births (Fig. 24.2). Whatever the cause, about 25% of all preterm births to mothers with one baby are ended early for maternal or fetal wellbeing. This is achieved either through the induction of labor or by planned cesarean section, depending on the reason for the early arrival and the conditions of the mother and baby. Fig. 24.1 Under-5 (years old) and infant mortality rates by region, 2003 Source: World Health Organization. Fig. 24.2 Various conditions leading to overall premature birth rates. According to American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) guidelines, labor should not be induced should prior to 39 weeks without a valid medical reason because of the increased risks. That leaves 75% of preterm labors as spontaneous. About a quarter of spontaneous preterm labors are due to premature rupture of membranes (see Chapter 20). Besides premature birth, other causes of perinatal mortality include congenital malformations, growth problems such as intrauterine growth restriction, multiple pregnancies, maternal low socioeconomic status (including social deprivation), lack of prenatal care, teenage pregnancies, and pregnancies of older women (above 40 years of age). Maternal mortality is difficult and complex to monitor, particularly in settings where the levels of maternal deaths are highest. Information is required about deaths among women of reproductive age, their pregnancy status at or near the time of death, and the medical cause of death—all of which can be difficult to measure accurately, particularly where vital registration systems are incomplete. The best estimate, according to the United Nations Chidren’s Fund (UNICEF), is that more than 500 000 women worldwide die each year from maternal causes. And for every woman who dies, approximately 20 more sufer injuries, infections, and disabilities in pregnancy or childbirth. The vast majority (99%) of the 536 000 estimated maternal deaths in 2005 occurred in developing countries. Slightly more than half of the maternal deaths (270 000) occurred in the sub-Saharan Africa region alone, followed by South Asia (188 000). Thus, sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia accounted for 86% of global maternal deaths. The four most important causes of maternal death past mid-pregnancy are hemorrhage (severe bleeding), infection, eclampsia-induced hypertension, and unsafe abortions (Fig. 24.3). Ectopic pregnancies also are a significant cause of maternal death, predominantly from hemorrhage and infection (see Chapter 13). There are also genetic and personal factors, such as race and age, that make pregnancy more risky for certain women. The maternal mortality rate for Black women (22.0 per 100 000 live births), for example, is almost three times the rate for White women (7.5 per 100 000 live births). Hispanics and other non-White women face significantly higher risks as well (Fig. 24.4). Being pregnant too young or too old also increases a woman’s mortality risks. Adolescents girls under age 15 years are five times more likely to die during pregnancy or childbirth than women over the age of 20. If they get pregnant between 15 and 19 years old, they are twice as likely to die than pregnant women 20–30 years old. Fig. 24.3 Most common causes of maternal death past mid-pregnancy and potential interventions to prevent them from occurring. Fig. 24.4 Maternal Mortality Rates in the United States by Race of Mother: 2000 National Center for Health Statistics. After women reach age 30 years, their mortality risk begins to increase regardless of race. Women aged 35– 39 years have approximately twice the risk of maternal death comapred with women aged 20–24 years. Since more than two-thirds of perinatal deaths occur in preterm infants, the appropriate management and/or prevention of preterm labor is likely to have a significant impact on perinatal mortality. Unfortunately, progress in the management of preterm labor has been hampered by our lack of understanding of the process of parturition in humans. Progress also has been hampered by the unavailability of drugs capable of inhibiting uterine contractility efficiently, without causing potentially serious side effects for the mother or the baby. Numerous studies have shown that beta-mimetics are effective at delaying delivery in women in preterm labor for 48 hours. However, there is no evidence that this relatively short delay provides any benefit in terms of perinatal mortality or morbidity. Studies also have found increased risk for various side effects in mothers, including chest pain, breathing difficulties, heart irregularities, headaches, and shaking. The potential for these multiple side effects must be shared with the patient before initiating any therapy. Short-term tocolysis with intravenous ritodrine may improve the outcome for the baby if it prevents delivery until the patient can be transferred to a hospital with better neonatal facilities or if it allows time for the mother to complete a course of antenatal glucocorticoids. Both human and animal studies have confirmed that glucocorticoids promote pulmonary maturation and reduce mortality in fetuses. Several studies indicate that prenatal glucocorticoids also stimulate renal maturation.

Definitions

Epidemiology and Etiology

Perinatal Mortality

Maternal Mortality

Management and Prevention

Perinatal Mortality

Pharmacological Management

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree