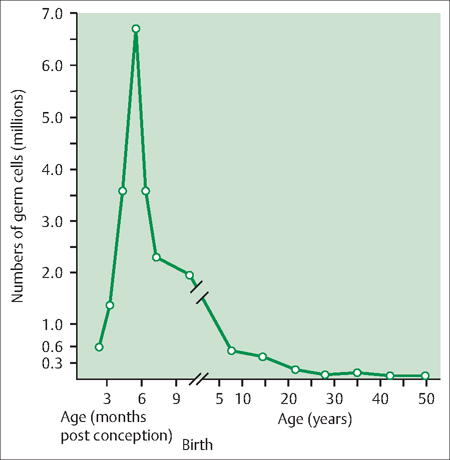

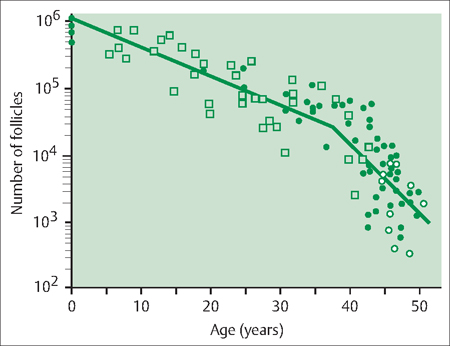

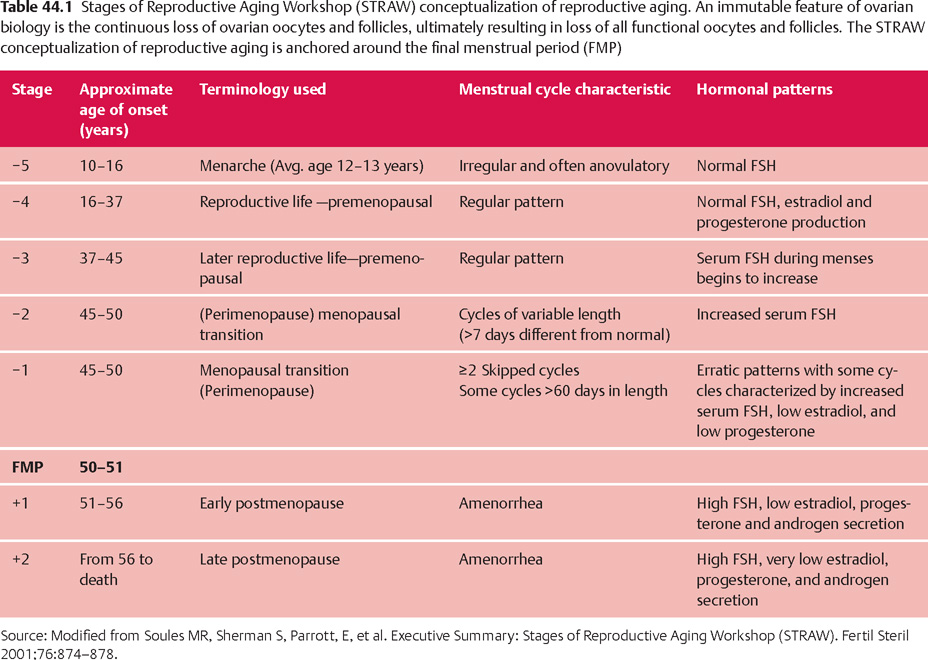

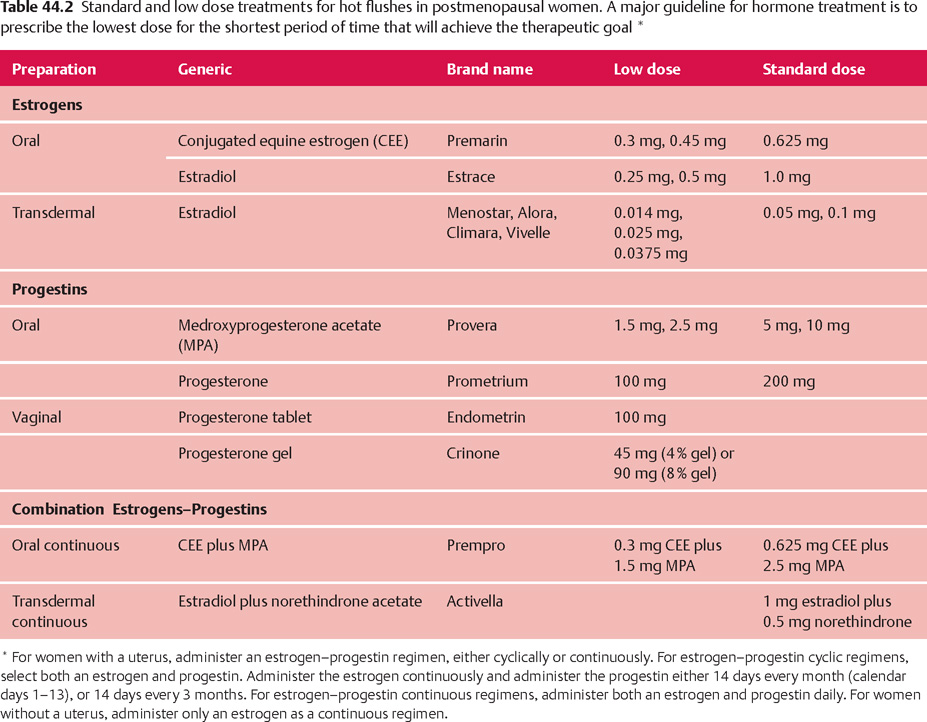

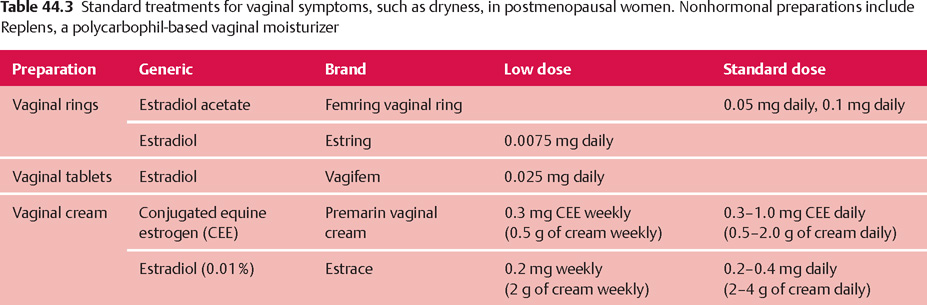

44 Perimenopause, Menopause, and Postmenopause: Consequences of Ovarian Reproductive Aging Robert L. Barbieri In 1900, the life expectancy of US women was 48 years. In 2005, life expectancy for women had increased to 80 years. The median age of menopause has been about 51 years for many centuries. Consequently, the proportion of time women spend in the postmenopausal state has increased dramatically. Determining the impact of ovarian aging and menopause on health is difficult because both aging and menopause affect organ physiology. Detailed scientific information identifying the relative impact on health of aging per se versus menopause is only beginning to become available. It is likely, as our understanding of both aging and menopause improves, that treatment approaches will change significantly. An immutable feature of ovarian biology is the continuous loss of a fixed, nonrenewable pool of oocytes and follicles. The loss of ovarian oocytes begins in utero. At 20 weeks of fetal development, the ovaries contain approximately 7 000 000 oogonia. At birth only 700 000 oocytes remain (Fig. 44.1). The loss of oocytes occurs in an exponential manner, meaning that a fixed percentage of oocytes are lost during each given period of time. The rate of loss of oocytes may accelerate after about 37 years of age (Fig. 44.2). Ultimately, the process ends with the loss of all functional oocytes and follicles. This results in: 1) a marked reduction in ovarian estradiol and progesterone production due to the absence of functional follicles, resulting in hot flushes and vaginal symptoms in many women; 2) permanent amenorrhea due to the absence of cyclic ovarian estradiol and progesterone production; and 3) sterility due an absence of functional oocytes. The continuous loss of ovarian follicles is the key feature of the process of female reproductive aging. The Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop outlined seven key stages in the process of reproductive aging (Table 44.1). The staging system is anchored around the final menstrual period (FMP), defined as Stage 0. Fig. 44.1 Changes in the total number of oocytes and follicles in human ovaries before and after birth The number of germ cells in the ovary peaks in utero during the second trimester of gestation From Baker TG Radiosensitivity of mammalian oocytes with particular reference to the human female Reproduced with permission of Elsevier from Am J Obstet Gynecol 1971;110:746–761. Premenopause (reproductive years), is characterized by regular ovulation and cyclic menstrual bleeding, except for intervals of pregnancy and lactation. The menopausal transition occurs beginning about three to five years before the onset of the final menstrual period. It is defined as the onset of variable cycle lengths, usually more than 7 days longer than the normal cycle length, ultimately resulting in multiple skipped cycles and absence of bleeding for more than 60 days. The menopausal transition is caused by increasing inability of the few remaining follicles to grow and ovulate in monthly cycles, leading to erratic patterns of estradiol and progesterone secretion and corresponding erratic menstrual patterns. Fig. 44.2 Bi-exponential model of declining follicle numbers in women up to 51 years of age Accelerated rate of follicle loss appears to occur after age 37 years From Faddy MI, Gosden R, Gougeon A, et al Accelerated disappearance of ovarian follicles in mid-life: implications for forecasting menopause Reproduced with permission of Oxford University Press from Hum Reprod 1992;7:1342–1346. Perimenopause includes both the menopause transition and the 12 months following the final menstrual period. For many authorities the “climacteric” and “peri-menopause” are synonyms. Menopause is the cessation of menstruation, defined as being present after 12 months of amenorrhea following the final menstrual period. The amenorrhea associated with menopause reflects the loss of functional ovarian oocytes and follicles. The median age of onset of menopause is 51 years. In a woman over the age of 45 years, in the absence of other plausible causes, 12 months of amenorrhea is likely to indicate the onset of menopause. Postmenopause is divided into two phases: the early postmenopause—the first five years following the final menstrual period—and the late postmenopause. During the early postmenopause, ovarian estradiol and progesterone reach nadirs that continue throughout the remainder of life. During early postmenopause, bone loss is accelerated owing to the decrease in ovarian estradiol, progesterone, and androgen production. The median age of menopause is approximately 51 years of age. About 5% of women have menopause after 55 years and about 5% have menopause between 40 and 45 years. About 1% of women have menopause before age 40 years. Menopause before age 40 years is considered to be clearly abnormal and is diagnosed as premature ovarian failure (see below). The age of onset of the first menses (menarche) is influenced by body mass, body composition, including body fat, exercise intensity, and general health. Over the centuries there has been a secular trend to an earlier age of menarche, in part, due to an increase in body mass and body fat at earlier ages. However, the age of menopause has not significantly changed for millennia. Some disease states result in an accelerated loss of ovarian follicles. For example, the genetic disorder 45,X, Turner syndrome, results in the very rapid loss of all ovarian follicles during childhood. At the age of puberty, there are no remaining follicles to secrete the estradiol necessary for breast development and onset of menarche. Consequently women with 45,X are menopausal before they reach menarche. Another genetic disease, galactosemia, results in the accumulation of high concentrations of galactose, an oocyte and follicle toxin, in the blood unless a strict galactose-free diet is consumed. In women with galactosemia who do not follow a galactose-free diet, premature menopause is common. Premature menopause has also been reported in women with myasthenia gravis, probably due to an autoimmune mechanism. Environmental exposures influence the age of menopause. For example, components of cigarette smoke are thought to be toxic to ovarian oocytes and follicles, resulting in their accelerated loss. The age of onset of menopause is approximately two years earlier in women who smoke. There is a dose-dependent relationship between smoking and early menopause. Alkylating chemotherapy agents, such as cyclophosphamide and radiation, are cytotoxic to both oocytes and follicle cells, and in adequate doses reliably cause premature ovarian failure. Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) is the primary hormone controlling the growth of an ovarian follicle. An ovarian follicle must reach a critical size and secrete a critical quantity of estradiol before it can trigger a pituitary luteinizing hormone (LH) surge, which in turn causes the follicle to ovulate. In primates, the feedback control between pituitary FSH and the ovary is set to cause one follicle to grow and ovulate each cycle. From a teleological perspective this tight regulation of FSH decreases the chance of ovulating multiple follicles in one cycle, which reduces the chance of twin and triplet pregnancy. Given the energy intensity of pregnancy, birth, and rearing of offspring among primates, singleton pregnancy is important for the health of the mother and offspring. Pituitary secretion of FSH is under negative feedback control of hormones secreted by ovarian follicle(s) including estradiol, inhibin A, inhibin B, and progesterone. During premenopause, the functionally “most competent” follicles respond to FSH, grow, secrete estradiol, which suppresses FSH, and ovulate. As women reach approximately 37–41 years of age, the remaining follicles appear to be less responsive to FSH stimulation. This requires the pituitary to secrete increasing quantities of FSH during menses to stimulate the growth of a follicle. As women enter the perimenopause, some follicles are markedly resistant to FSH stimulation. In a perimenopausal woman, when an available follicle is intensely resistant to FSH, the pituitary secretes massive amounts of FSH in an attempt to cause the follicle to grow and secrete estradiol. If the follicle does not respond, the cycle is characterized by high levels of FSH, low levels of estradiol and light menstrual bleeding. These cycles are often anovulatory. In a subsequent cycle, if the next available follicle(s) is somewhat more responsive to FSH, the massive quantities of FSH released throughout the previous cycle may carry over into the following cycle, causing the follicle to grow quickly and secrete excessive amounts of estradiol. The excessive estradiol secretion, in turn, exerts negative feedback on FSH, causing FSH levels to fall to levels observed in young premenopausal women. Therefore, this cycle is characterized by low levels of FSH during most of the cycle, abnormally high levels of estradiol, and heavy menses. The oscillation between cycles with poor follicle responsiveness (high FSH, low estradiol, light menses) and an overstimulated follicle (low FSH, high estradiol, heavy menses) is a major feature of the perimenopause interval. The oscillation between light and heavy menses is often troubling to perimenopausal women. To prevent the FSH-follicle oscillation, pituitary secretion of FSH must be definitively suppressed. Suppression of pituitary FSH cannot be accomplished with doses of estrogen—progestin typically used to treat hot flushes and vaginal symptoms (Tables 44.2, 44.3). Suppression of pituitary FSH secretion during the perimenopausal stage requires the doses of estrogen—progestin used in standard hormonal contraceptives, which are in general about five to eight times higher than doses used in hormone therapy for postmenopausal women. When all functional ovarian follicles are depleted, there is no hormonal negative feedback control of FSH secretion. Circulating FSH is markedly increased in postmenopausal women. Circulating estradiol, progesterone, inhibin A, and inhibin B are markedly decreased in postmenopausal women. Many symptoms have been reported to be associated with perimenopause and postmenopause, but symptoms caused by aging may confound these associations. After carefully controlling for aging, the perimenopause and postmenopause are thought to be reliably associated with four symptoms: As defined in the STRAW staging system, the onset of perimenopause is first characterized by irregular menstrual cycle length, with a pattern more than 7 days different from the patient’s typical menstrual cycle length. In some women, the onset of menstrual cycle irregularity results in more frequent menses with cycle lengths less than 24 days. Almost all menstrual cycles less than 24 days in length are anovulatory cycles. In other women, the onset of menstrual cycle irregularity results in less frequent menses with cycle lengths greater than 35 days. As the patient approaches the final menstrual period, they may experience cycles more than 60 days in length. From a simple viewpoint, this represents a “skipped period.” The perimenopause and postmenopause are often characterized by the onset of hot flushes, which occur in most women. Both rapidly changing serum concentrations of estradiol (perimenopause) and very low concentrations of estradiol (postmenopause) are thought to destabilize hypothalamic regulatory centers, resulting in the phenomenon of hot flushes. Hot flushes occur most frequently in the perimenopausal transition. Hot flushes are less commonly reported by Chinese and Japanese women. Hot flushes typically begin as the sudden onset of the sensation of warmth or heat on the face, neck, and chest, which may spread throughout the body. The sensation can be intense and associated with sweating followed by chills and shivering. Hot flushes are especially common at night and may wake the patient from sleep. Severe hot flushes can prevent women from entering stages of deep sleep associated with dreaming, and may contribute to insomnia and irritability. Hot-flush—like symptoms may also be caused by hyperthyroidism, carcinoid, and pheochromocytoma. Medications that may cause hot flushes include anti-estrogens such as tamoxifen, aromatase inhibitors such as letrozole or anastrozole, and GnRH analogues such as leuprolide, niacin, and nitrates. For most women, hot flushes will improve in about 30% of women in a few months and in 90% of women within 5 years. About 10% of women will experience hot flushes, often without improvement, for many years. The prevalence of vaginal symptoms, including dryness, discomfort, itching and dyspareunia, increases from about 10% in the perimenopause to over 50% in the late postmenopause. Vaginal symptoms are probably due to low levels of estradiol and androgens, and aging. Postmenopausal women have decreased vaginal blood flow and decreased vaginal secretion; and increased fragmentation of vaginal elastin. As noted above, after carefully controlling for aging, the perimenopause and postmenopause are thought to be reliably associated with four symptoms:

Definition and Diagnosis

Etiology and Epidemiology

Physiology of Ovarian Aging

Clinical Presentation

History

Menstrual Cycle Irregularity

Hot Flushes

Vaginal Symptoms

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree