Pediatric Neck Trauma

Henry E. Rice

Division of Pediatric Surgery, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina 27710.

Children have a high incidence of traumatic injuries to the head and neck. Almost two-thirds of children admitted to trauma centers in the United States have injuries to the head, face, or neck (1). Furthermore, multiple injuries in children with head and neck trauma are common because 50% to 70% of children with neck and facial trauma have other bodily injuries. Although the management of pediatric neck trauma is similar to the care of these injuries in adults, the practitioner involved in the management of injured children needs to pay attention to specific anatomic, growth, and developmental concerns of the child. This chapter reviews the evaluation and surgical management of injuries to the necks of children. Separate chapters address the management of pediatric head and cervical spine injuries.

INITIAL TRIAGE AND MANAGEMENT

The care of children with neck trauma follows the basic principles of trauma care. The approach to care of the child with a neck injury should follow the American College of Surgeons’ Advanced Trauma Life Support protocols for primary survey, resuscitation, secondary survey, and definitive care (2). Because multiple-system injury is the rule rather than the exception, every organ system in the injured child requires evaluation for any potential injury. Children with head and neck injuries often require the coordinated effort of multiple specialty teams.

Airway control is the highest priority of care, and rapid inspection for airway patency, air movement, crepitus, hoarseness, and subcutaneous emphysema are the first steps in the evaluation of neck trauma. Supplemental oxygen should be administered, and adequate lighting and suction are essential. Although the anatomy of the upper airway varies with the age of the child, the best method for restoring immediate airway patency for any child is the jaw-thrust maneuver followed by removal of debris from the mouth. Careful inline cervical traction is necessary to minimize worsening any potential spine injury.

Because small infants may be obligatory nasal breathers, facial injuries that occlude the nostrils may obstruct their airway. In small infants, orogastric tubes should be used to decompress the stomach. Although complete obstruction of the airway in children is relatively uncommon, airway control is necessary for the management of significant head injury or shock. In the case of failure of these maneuvers to secure an airway, immediate airway intubation is required.

Several steps are necessary for intubating the airway of an injured child. Preoxygenation and pharmacologic preparation with sedatives and paralytics will facilitate airway control. All children requiring intubation should be assumed to have a full stomach and are at risk for aspiration. Cricoid pressure should be applied during intubation, especially in young infants where the occiput may provide passive flexion of the neck and limit the visualization of the epiglottis. The trachea in the newborn measures approximately 5 cm in length and grows to 7 cm by 15 months. Failure to appreciate this short length may result in bronchial intubation. The tube must be positioned at a point where bilateral breath sounds are audible and the chest rises symmetrically.

The choice of the correct size endotracheal tube is critical. An endotracheal tube which is too small will add resistance to ventilation and can become obstructed from secretions or blood. Similarly, too large a tube will produce unnecessary pressure against airway mucosa and increase the risk of airway inflammation, necrosis, and subglottic stenosis. Uncuffed endotracheal tubes, which fit loosely and allow for some air leak, are used for children less than 25 kg.

In the rare case of complete or near complete airway obstruction, placement of a surgical airway may be necessary.

In young children, an airway should be secured by a needle cricothyroidotomy. Tracheotomy in the emergency room setting is a technically procedure in a demeading environment because of a child’s unique limited anatomy, as well as limitations in equipment, and lighting. A needle cricothyroidotomy allows sufficient ventilation and oxygenation to proceed to the operating room, where a formal tracheostomy can be performed. However, in an emergent condition, it is clearly preferable to perform a surgical cricothryoidotomy rather than to risk asphyxia while awaiting definitive airway control.

In young children, an airway should be secured by a needle cricothyroidotomy. Tracheotomy in the emergency room setting is a technically procedure in a demeading environment because of a child’s unique limited anatomy, as well as limitations in equipment, and lighting. A needle cricothyroidotomy allows sufficient ventilation and oxygenation to proceed to the operating room, where a formal tracheostomy can be performed. However, in an emergent condition, it is clearly preferable to perform a surgical cricothryoidotomy rather than to risk asphyxia while awaiting definitive airway control.

Once an airway is established, breathing must be assessed and ventilatory assistance provided. The mediastinum of an infant is mobile and does not protect the opposite lung from compression by a hemothorax or pneumothorax. Similarly, a ruptured diaphragm with herniation of abdominal viscera may significantly impair ventilation. Finally, gastric dilatation will significantly limit a child’s ability to ventilate, and children should routinely have a nasogastric or orogastric tube placed to evacuate gastric contents.

Following assessment of a child’s airway and breathing, attention must be given to evaluating and stabilizing circulation and control of hemorrhage. In general, most bleeding from neck wounds can be controlled with direct pressure, although nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal bleeding often requires packing or surgical control of bleeding vessels. In particular, scalp wounds can be the source of large blood loss, and rapid manual control is required to limit hemorrhage prior to wound closure. Simply wrapping the skull with rolled gauze or compression wraps can rapidly control profuse scalp bleeding.

Applied Surgical Anatomy

Management of the pediatric patient with severe neck trauma requires attention to anatomic concerns. Compared with an adult airway, the larynx and trachea of children are relatively small, and airway obstruction from blood or other debris is more common. In addition, because the ratio of smooth muscle in comparison to cartilage is greater in the pediatric airway, the presence of foreign material in the airway is more likely to cause bronchospasm.

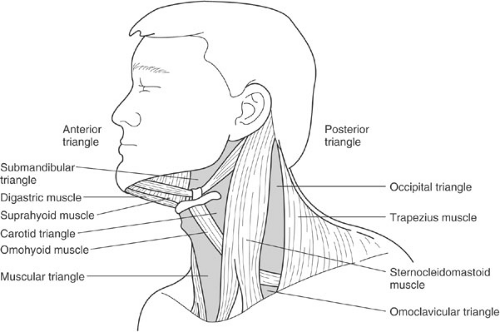

The neck is classically divided into several anatomic triangles (Fig. 24-1). Wounds to the posterior triangle infrequently involve the esophagus, airway, or major vascular structures, although these structures can be injured with deeply penetrating anterior directed wounds. The wound is directed sharply anteriorly. Intrathoracic injury can occur if a penetrating wound is directed inferiorly. In contrast, penetrating wounds that enter through the anterior triangle carry a greater likelihood of vascular, airway, or esophageal injury.

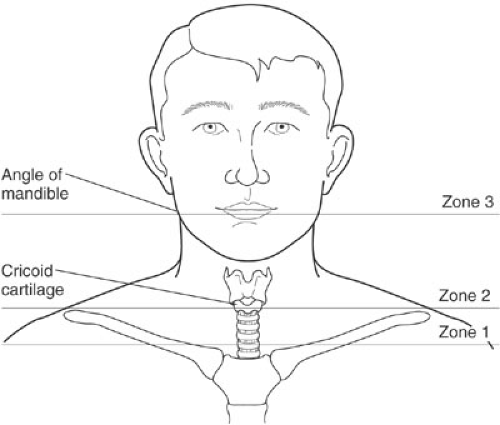

For the specific management of penetrating injuries, the anterior neck is further divided into three zones defined as horizontal planes (Fig. 24-2). Zone I represents the base of the neck and extends from the sternal notch to the top of the clavicle or the cricoid cartilage. Injuries in Zone I carry the highest risk of major vascular and intrathoracic injury. Zone II is the middle and largest portion of the neck, and extends from the top of zone I to the angle of the mandible.

Zone II injuries carry a lower mortality rate than either zone I or III injuries because injuries are generally apparent and exposure of vital structures can be readily accomplished. Zone III encompasses the neck above the angle of mandible, and surgical exposure in this zone can be particularly difficult. The risk of injury to the distal carotid artery, salivary glands, and pharynx is greatest in zone III.

Zone II injuries carry a lower mortality rate than either zone I or III injuries because injuries are generally apparent and exposure of vital structures can be readily accomplished. Zone III encompasses the neck above the angle of mandible, and surgical exposure in this zone can be particularly difficult. The risk of injury to the distal carotid artery, salivary glands, and pharynx is greatest in zone III.

The other major anatomic landmark in the neck is the platysma muscle. This thin broad muscle lies just beneath the skin, covering the entire anterior triangle and anteroinferior aspect of the posterior triangle. Wounds that do not penetrate the platysma are considered superficial and generally do not warrant further extensive evaluation. In contrast, penetrating wounds through the platysma require hospital admission and further evaluation, as detailed later in this chapter, to detect major injuries.

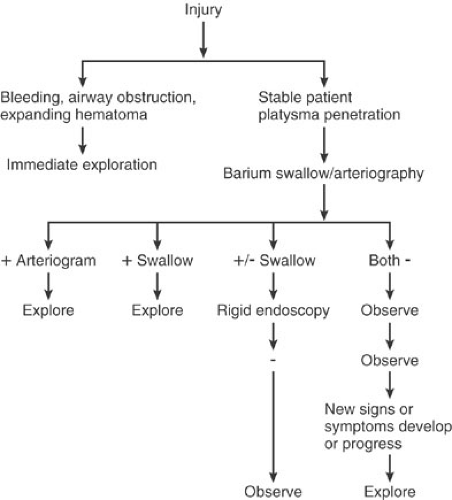

SELECTIVE VERSUS MANDATORY EXPLORATION

One of the more controversial areas in pediatric trauma is the management of the stable child with penetrating anterior neck wounds that traverse the platysma muscle (3,4,5,6). For many years, two distinct schools of clinical practice have existed for treatment of these injuries. The first advocates mandatory surgical exploration for all patients; the other recommends diagnostic testing to selectively identify patients requiring operative exploration (Fig. 24-3). Others have advocated simply observing the stable patient with a neck injury, although the high mortality of patients requiring surgical exploration after a period of observation has limited the acceptance of this approach. Although there is little evidence-based literature in pediatrics comparing these approaches, the management of these injuries in children closely follows the clinical practice for adults.

Advocates of mandatory neck exploration for penetrating injuries cite the low morbidity of surgery as justification for a “negative” exploration rate of 50% to 60% (7). Others suggest that the inaccuracy of standard methods for evaluation of neck injuries, as well as the delay in diagnosis, can increase the morbidity of severe injuries (7). The inaccuracy of nonoperative management has been examined in a prospective manner in adults with penetrating zone II injuries without hemorrhage who underwent arteriography, laryngobronchoscopy, esophagoscopy, and esophagography, followed by mandatory neck exploration. Five of 113 patients had normal preoperative clinical and diagnostic findings; however, at operation six major injuries were found in these patients (8). Although no similar prospective clinical studies have been performed in children, it is possible that similar diagnostic inaccuracies would exist. The outward physical appearance of a simple neck wound is not necessarily helpful in identifying major injuries because at least 5% of wounds that appear benign can harbor significant injuries (9). With a mandatory operative strategy, angiography is generally indicated for penetrating

injuries to zones I or III to identify injuries to the thoracic or intracranial vessels. However, the use of Duplex ultrasound imaging of the carotid artery to identify injuries has been advocated for adults to be an effective screening modality for carotid artery injuries and may play a role in the care of children (10).

injuries to zones I or III to identify injuries to the thoracic or intracranial vessels. However, the use of Duplex ultrasound imaging of the carotid artery to identify injuries has been advocated for adults to be an effective screening modality for carotid artery injuries and may play a role in the care of children (10).

In contrast, advocates of selective exploration for the child without obvious signs of a major neck injury cite the high cost per “positive” exploration, and the fact that some injuries are missed despite surgical exploration (4,5). In centers that support this approach, the availability of angiography, panendoscopy, and esophagography is essential to allow a selective management plan. In general, if a selective approach is used for the management of penetrating neck trauma, angiography, esophagography, and/or esophagoscopy are performed for all children, and generally bronchoscopy. Esophageal endoscopy (rigid or flexible) should be considered complementary to esophagography, and the choice of methods to evaluate for esophageal injury should be based on local hospital resources and experience.

More recent modifications of approach to the patient with penetrating neck injury has included selective identification of patients who require extensive imaging. Recent literature in adults with penetrating zone II injuries has suggested that high-resolution helical computed tomography (CT) scan alone can be used to identify potentially severe neck injuries that warrant surgical exploration (11,12,13). Axial CT images often can demonstrate the trajectory of the penetrating injury. This information can provide objective evidence of proximity and injury to neck vessels, delineation of spine fractures and spinal canal involvement, and potential pharyngoesophageal injury (14). At present, no current literature has addressed the utility of CT scan alone in children for evaluating penetrating neck injuries. However, it is likely that, as CT imaging techniques continue to improve, this imaging option will become more central for the care of these children.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree