Patient and Family-Centered Care

Jeffrey M. Simmons, Stephen E. Muething, and Kathleen L. Dressman

DEFINITION

The philosophy of patient and family-centered care is founded on the belief that health outcomes are improved by partnering among health care providers, patients, and their families. This belief permeates the health care system and does not represent a specific therapy that is applied as part of a treatment plan. In the literature, there is no uniform definition of patient and family-centered care. Therefore, it is best described by its fundamental principles: respect and dignity, information, participation, collaboration, and flexibility.

RESPECT AND DIGNITY

RESPECT AND DIGNITY

Treat each family with respect. Although individual physicians and nurses typically are respectful in their interaction with patients, the health care system was not designed to afford dignity and respect to patients. The system often values providers’ needs and time over that of patients (waiting rooms, double-booked schedules, etc). Patients are often referred to by numbers or diagnoses. Patients in a hospital setting are often asked to wear uncomfortable clothing and are subject to rules beyond their control. Many of the routine policies and procedures that seemingly disregard patients’ comfort and dignity are now changing. Treating patients and families with honor, addressing them as they wish to be addressed, asking permission to examine, and learning about their strengths and human history in addition to their medical history exemplifies this core principle of respect and dignity. Consideration must be given to physical comfort and modesty of patients and families. Families must be included in discussions regarding their care and treatment plan. This was successfully accomplished at one major children’s hospital by instituting a system of “family-centered rounds” that included the family in all discussions and planning decisions regarding diagnosis and care. Family and care team satisfaction improved.1

INFORMATION

INFORMATION

Access to health information is a basic right of patients. Implementing the patient and family-centered care philosophy involves transfer of control of information from the health care system to the patient and family. Respecting the absolute confidentiality of information as it is used by the health care system is imperative.

Traditional paper charts kept separately by each provider and hospital are being replaced by interconnected electronic health records and databases. As the electronic system is implemented, designers are faced with the decision of who “owns” the information. Many hospitals now give patients complete access to their charts during a hospital stay. Some give the patient control of all information, and the patient or family grants access to hospitals or physicians. This is particularly helpful for families of children with chronic conditions who previously needed to wait for busy professionals to contact them with test results. They worried about delays in care and information being overlooked. Access promoted improved self-management and interaction with providers.2 The Internet allows patients to have nearly the same access as physicians to the health literature. Patients and their families are coming to expect access to all pertinent information. Not all patients read available literature, but most want the access. Access also includes information regarding the performance of the health care system, such as comparative outcome data and patient safety issues.

PARTICIPATION

PARTICIPATION

Perhaps this principle can best be summed up by the phrase “Nothing about me, without me.” Families and patients have the fundamental right to make decisions regarding their care. Therefore, families need to be presented with choices. Shared decision making is gaining attention as an important aspect of caring for children with chronic and serious conditions. Increasing emphasis is placed on presenting information in a clear manner and allowing patients to make choices when they desire. Involving families actively in making choices regarding care approaches appears to improve engagement and compliance.3

COLLABORATION

COLLABORATION

Collaborate with families to improve the health care system. Many health care organizations have found families are a great resource of energy and expertise that often goes underutilized. Most pediatric hospitals have developed family advisory councils; some have patient advisory councils for teens. Families are more frequently becoming members of governing boards of hospitals. Several hospitals have families serving on quality improvement teams and facility design teams. For individual patients, there is increasing awareness of the benefits of support by family and friends during acute hospital stays. In addition, there is support from the literature that parent-to-parent support may be crucial for families whose child has a chronic or serious condition. Parents state that fears and anxiety can sometimes be better allayed by parents who have experienced similar situations.4

FLEXIBILITY

FLEXIBILITY

It is important to recognize that illness places a significant burden on families. To truly partner with patients and families, systems must be flexible and address families’ and patients’ unique circumstances and needs. Offering expanded and flexible hours for office visits, tests, and even surgery may be necessary. Of course, the needs of the families of physicians and nurses and staff must also be considered. Some chronic care clinics are allowing patients to determine the content and focus of a clinic visit. Most patients choose the routine aspects of a visit, but some have more individual needs. Alternative methods of interacting with patients are becoming common place. Phone visits, e-mail advice, text messaging, and alternative sites of care (eg, school-based health centers) all allow for flexibility. More patients want to use alternative medicine. Physicians must be flexible in accommodating the choices families make. In hospital settings, flexibility that allows increased control of daily schedules by the patient can both assure that appropriate care is provided in a timely manner and can empower patients to become more engaged in their care. This is of particular value for care of adolescents with chronic disorders requiring frequent hospitalization such as cystic fibrosis.5

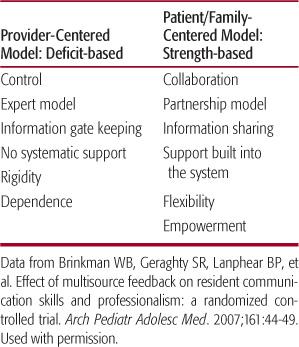

As entire organizations, health care clinics, hospital units (microsystems), and individual providers work toward the principles of patient and family-centered care, a paradigm shift takes place (Table 7-1).

IMPLEMENTATION OF PATIENT AND FAMILY-CENTERED CARE

IMPLEMENTATION OF PATIENT AND FAMILY-CENTERED CARE

Because each practice, clinic, and other health care facility has its unique norms and culture, the approach to implement the philosophy of patient and family-centered care must be customized to the environment: There is no one-size-fits-all approach.

To ensure sustainability of your patient and family-centered care strategies, a 3-pronged approach is recommended. Strategies must be aimed at the strategic or organizational level, the microsystem or point-of-care level (eg, on the unit, in the clinic), and the individual practitioner level. Short-term gains may be achieved if one of these levels of care is targeted in a specific clinical setting but families can become frustrated by variances in care approaches across an organization. Thus, full implementation of a patient and family-centered care approach requires organizational change, as discussed in the additional material provided electronically.

HEALTH PROVIDER EDUCATION

An important challenge in implementing patient and family-centered care in many health care environments is how to train new providers—medical students, residents, nursing students, and other allied health trainees—to deliver care that is patient and family centered. Part of the challenge is in introducing new personnel to the patient and family-centered care philosophy, which likely differs from their previous training, while another part is the frequent turnover of new trainees.  Trainees need to observe the approaches used by skilled practitioners in this care setting, be given the chance to demonstrate their evolving skills, and, perhaps most importantly, be given concrete feedback about their skills and performance.

Trainees need to observe the approaches used by skilled practitioners in this care setting, be given the chance to demonstrate their evolving skills, and, perhaps most importantly, be given concrete feedback about their skills and performance.

Multiple practical methods of teaching principles of patient and family-centered care have been described. Family, faculty, parents, and caregivers of children with chronic medical needs can be utilized in a variety of instructional methods: as lecturers, small group discussion leaders, participants in role plays, and hosts of home visits.7 Their participation in multidisciplinary bedside hospital rounds (often called family-centered rounds) also facilitates learning of patient and family-centered care principles,8 as does bedside nursing change-of-shift handoffs.9 Both techniques blend previously separated functions of teaching and working to create a care environment in which the patient and family are the center of and included in conversations about both care and teaching.

Finally, patients and families should be included in the learner evaluation process. Incorporating patient and family evaluations into formal evaluation and feedback processes provides perspective beyond that gained by direct observation by instructors and can lead to improved overall skill and performance.1,10,11

REFERENCES

See references on DVD.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree