The patella, which begins to ossify between ages 3 and 6 years, is uniquely flexible in younger children.4 Anywhere between one and six ossicles will form and merge into a single unit through intramembranous ossification, which then spreads peripherally. Until ossification is complete, the periphery of the ossifying patella may normally appear irregular on radiographs and should not be mistaken for patellar pathology. Bipartite or multipartite patella, representing incomplete coalition of ossicles, are reported in between 2% and 15% of adolescents and are important as part of any differential diagnosis that includes patella fracture in this age group.5,6 However, the most common location of an accessory ossicle is the superolateral pole compared with patellar sleeve fractures, which more commonly occur in the distal half of the patella.

The vascular supply of the patella comes predominantly from the paired superior and inferior geniculate arteries. They converge, predominantly anteriorly, to form an anastomotic circle surrounding the patella. Additional branches enter from below the distal pole posterior to the patellar tendon.7 Vascularity is important to take into account when considering fixation, as the blood supply of the patella arises from the anterior surface and distal pole.

EPIDEMIOLOGY/MECHANISM OF INJURY/ETIOLOGY/PATHOMECHANICS

As the skeletally immature patella is more cartilaginous than in adults, it is more accommodating to three-point bending.8 A forceful quadriceps contraction with the knee in flexion creates a fulcrum effect. In skeletally immature patients, the collagen of the tendon blends directly with the cartilage, as opposed to adults in whom Sharpey’s fibers form a robust connection between the tendon and its bony attachment site. With the eccentric force of the quadriceps, the weakest part of the construct, the connection between the cartilage and bone, is the most vulnerable site of fracture with excessive forces.9

Sleeve fractures of the patella are the most common type of patella fracture in preadolescents and adolescents. They usually do not occur before the age of 8 years or after skeletal maturity, with an average age of 12.7 years and a 3:1 male predominance.2 Inferior avulsions are most common, but superior avulsions have also been reported and are more likely to be nondisplaced.10

In the patient’s described injury history, there is usually an identifiable traumatic event, with the patient reporting a jump, landing from a jump, or a sudden fall. If there is no specific event, and the patient simply began to have pain after an athletic event or after a period of significant activity, other diagnoses such as a symptomatic bipartite patella or Sinding-Larsen-Johansson syndrome—a traction apophysitis specific to the inferior pole of the patella9—should be considered more strongly. Questions regarding symptomatology in the preceding weeks to months, even if mild, may be helpful in identifying an acute exacerbation of more chronic pathology rather than a fracture. A direct blow to the patella is a possible mechanism of injury for a patellar sleeve fracture, but less likely. Difficulty with weight bearing is common, and patients will often be unable to bring the knee into full extension. Rapid swelling and bruising are also commonly reported.

On physical examination, prepatellar swelling and ecchymosis, as well as a tense effusion, are frequently seen. Aspiration can alleviate some symptoms and confirm hemarthrosis but is seldom performed today, compared with traditional practices. Lack of full extension and inability to complete a straight-leg raise is common. However, if the retinaculum is intact, there may not necessarily be an extension lag. Patients may also internally rotate the leg and use the fascia lata to complete a straight-leg raise.9 Commonly, a defect inferior to a high-riding patella, or patella alta, can be palpated.

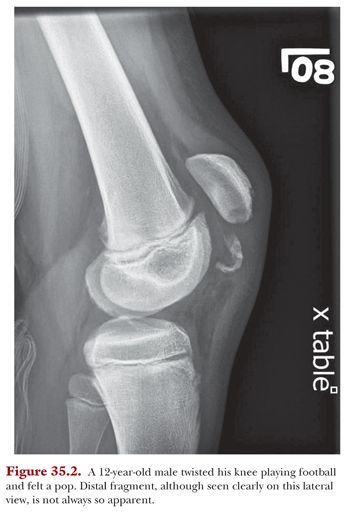

Meticulous evaluation of imaging is paramount in the diagnosis, as patellar sleeve fractures are frequently missed or underappreciated. Two orthogonal view radiographs are usually sufficient, although oblique views may more conclusively delineate the pathoanatomy. A bony fragment distal to the inferior pole of the patella ranging in size from a small fleck of bone (within a larger unossified fragment of patellar cartilage) to a larger sleeve of ossified distal pole (Fig. 35.2) is usually best seen on the lateral view. Amount of displacement is important, as it determines treatment selection. The most important aspect of radiographic interpretation, however, is that a small osseous opacity almost always represents a much larger fractured osteochondral fragment.11,12 Contralateral films may therefore be helpful, as a small, nondisplaced, or minimally displaced well-corticated ossicle may more likely represent Sinding-Larsen-Johansson syndrome or a bipartite patella, as opposed to a true sleeve fracture.13 Because of the importance of understanding the precise pathoanatomy of such injuries, we consider magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to be invaluable in determining the extent of injury in equivocal cases or those unclear from plain radiographs alone, as well as assessing the size of fragment and for preoperative planning, when applicable.11 MRI will demonstrate the cartilage contiguous with the small osseous component (Fig. 35.3) and generally elucidate the injury pattern more precisely.