Richard D W Hain With contributions by, Megumi Baba, Joanne Griffiths, Susie Lapwood, YiFan Liang, Mike Miller A child’s illness profoundly impacts on child and family, particularly when the illness might lead to death. The science of medicine is increasingly able to intervene to cure even serious illness. However, a significant number of children cannot be cured. They have a ‘life-limiting condition’ (LLC), an illness which leads to premature death and/or a prolonged period of chronic illness. If cure is the only solution medicine can offer, doctors will never meet the needs of children living with LLC. Cure is a powerful way to improve the lives of ill children; fortunately, it is not the only way. Unlike most medical specialties, palliative care is not defined by organ system, aetiology or age group, but by a philosophy of care. That complicates definitions. There have been many attempts to define which medical conditions are included in LLC. The most widely used is the ACT/RCPCH system, which defines four categories of LLC based on the trajectory of the condition. Conditions in the different categories are: • Category I – those for which death and cure are both possible outcomes (e.g. cancer). • Category III – relentlessly progressive towards death without any such normal period. The exact proportions are not clear (see below), but some reports suggest that categories I and IV each account for roughly a third of all LLCs, with II and III together making up the remaining third. The multidimensional nature of palliative care means that it is informed by research in a wide range of disciplines, from anthropology – for example, Bluebond-Langner’s seminal work on how children see dying – to bioethics, moral philosophy and theology. Over the last fifteen years, it is perhaps in the fields of opioid pharmacology and epidemiology that the impact of scientific research is most obvious to paediatricians. One of the barriers to good symptom management has traditionally been the belief that morphine should be withheld from children wherever possible, and that codeine was safer because it was weaker. A series of studies of morphine in children has shown that there is no pharmacological basis for a reluctance to prescribe morphine in children. In contrast, recent clinical studies have shown that the metabolism of codeine is dangerously unpredictable. Studies have made it clear that conventional practice in respect of opioids in children perversely recommended an alternative to morphine that was both less effective and more dangerous. Epidemiology is beginning to shape palliative care. The ACT/RCPCH categories are descriptions of types of condition, rather than a list of diagnoses. They are not precise enough for epidemiological purposes. That has meant that, until recently, it was impossible to develop services for children with LLCs based on evidence. That has recently changed as a result of studies. One assigned an ICD10 code to around 400 of the commonest LLCs presenting to hospice and palliative care teams in the UK. Another used an analysis of prospective ‘hospital episode’ data. The result was that for the first time we now know that 32 in every 10,000 children in England are living with a LLC and that its prevalence has increased by almost a third in the last decade. Palliative care in children provides a good illustration of the need for clinical practice to be informed by science, even when cure is no longer possible. Pharmacology and epidemiology are fields of research whose findings have begun to transform the way we can care for children with LLCs. Pain management: • Is an essential component of palliative care. • Requires assessment, communication, planning and a sound knowledge of pharmacology and physiology. • Is often under-recognized in children with disability. • Can dramatically improve quality of life for child and family if done well. According to the International Association for the Study of Pain, pain is ‘an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage.’ It is: • Subjective (whatever the child says it is) • Influenced by past pain experiences and concerns about personal well-being or that of others All children, including the extremely preterm, are able to feel pain. Pain in palliative care is usually neither wholly acute nor entirely chronic. It has elements of both, and may be complicated by the existential context of deterioration towards death. Assessment of pain in children requires: • Detailed history (also from the child, if possible) • Observation of the child (Box 34.2), ideally in a variety of settings • Consideration of all possible contributing factors (including psychological, spiritual and social) • Discussion with parents, especially in the non-verbal child • Use of pain assessment tools appropriate for age and cognitive ability. The two most commonly-used types of pain scale are ‘faces’-type tools and scales based on observation of behaviour patterns associated with pain in non-verbal children, such as the Paediatric Pain Profile. Faces-type tools are based on a Likert scale and illustrate varying pain intensity using drawings of children’s faces. Unlike the Paediatric Pain Profile, most ‘faces’-type scales were validated for assessment of acute pain in cognitively normal children, rather than in children with LLCs. There are three steps on the WHO pain ladder. As pain intensity increases and the effect of prescribing on one step becomes inadequate, the prescriber should move to the next step. Each step is characterized by: • A specific class of analgesic • A specific approach to dosing (regular versus ‘as needed’) • The need to consider adjuvants (Box 34.3) appropriate to the nature of pain For prescription of major opioids (Box 34.4), there are three phases, namely: initiation, titration and maintenance. The opioids can be given as immediate release (e.g. oramorph, buccal diamorphine), continuous release (e.g. MST, transcutaneous patch, syringe driver). There should always be both regular (background) and ‘as needed’ doses. This is a specialist skill and should be undertaken in discussion with the local or regional palliative care team. Nausea and vomiting due to: Additional factors to consider are: • Functional delay – can use prokinetics (dopamine antagonists, erythromycin) • Steroids can be valuable by reducing: – Oedema (e.g. in raised intracranial pressure) – Release of emetogenic mediators In bowel obstruction, consider: • Anticholinergic to relieve spasm (hyoscine butylbromide (buscopan)) • Analgesic to relieve pain (strong opioid parenterally) Gastro-oesophageal reflux (GOR) is common but does not always cause discomfort. The risk is increased by prone position, decreased activity, medication and liquid feeds (all more likely among debilitated patients). A presumptive diagnosis and treatment of GOR may be appropriate in pain and discomfort related to feeding without an obvious cause. In reflux, consider: • Antacid to relieve pain (ranitidine, proton blockers) • Prokinetic to improve gastric emptying (domperidone, metoclopramide) • Dopamine blocker to reduce reflux (domperidone, metoclopramide)

Palliative medicine

Philosophy of palliative medicine

Symptom control

Pain

Assessment of pain

Management of pain

Consider and treat specific reversible causes

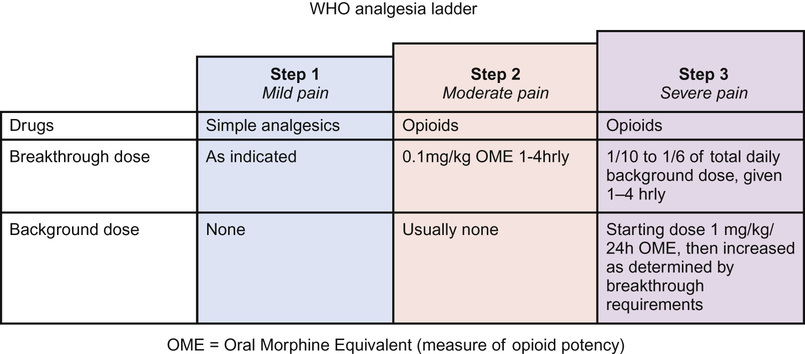

Pharmacological approach: the pain ladder

Nausea and vomiting