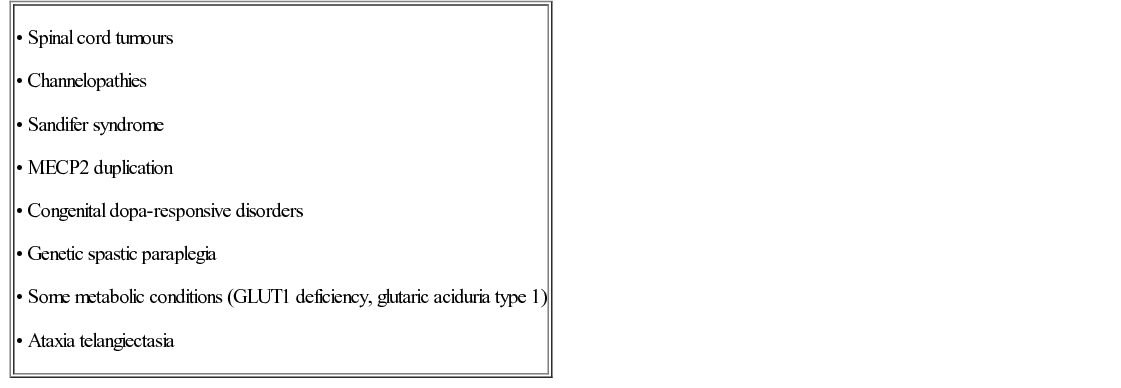

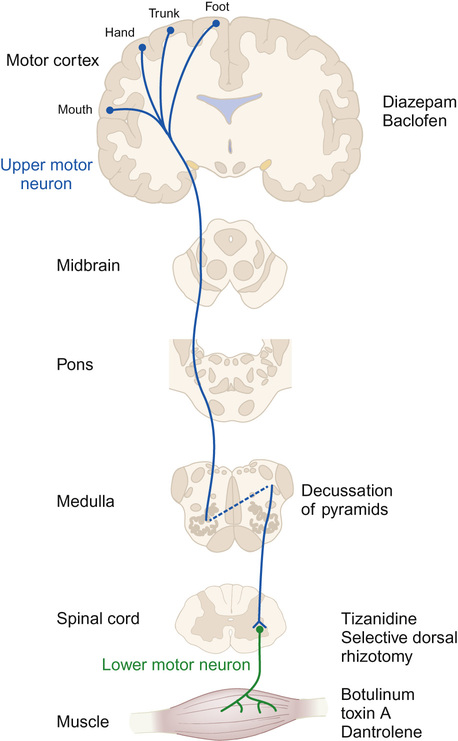

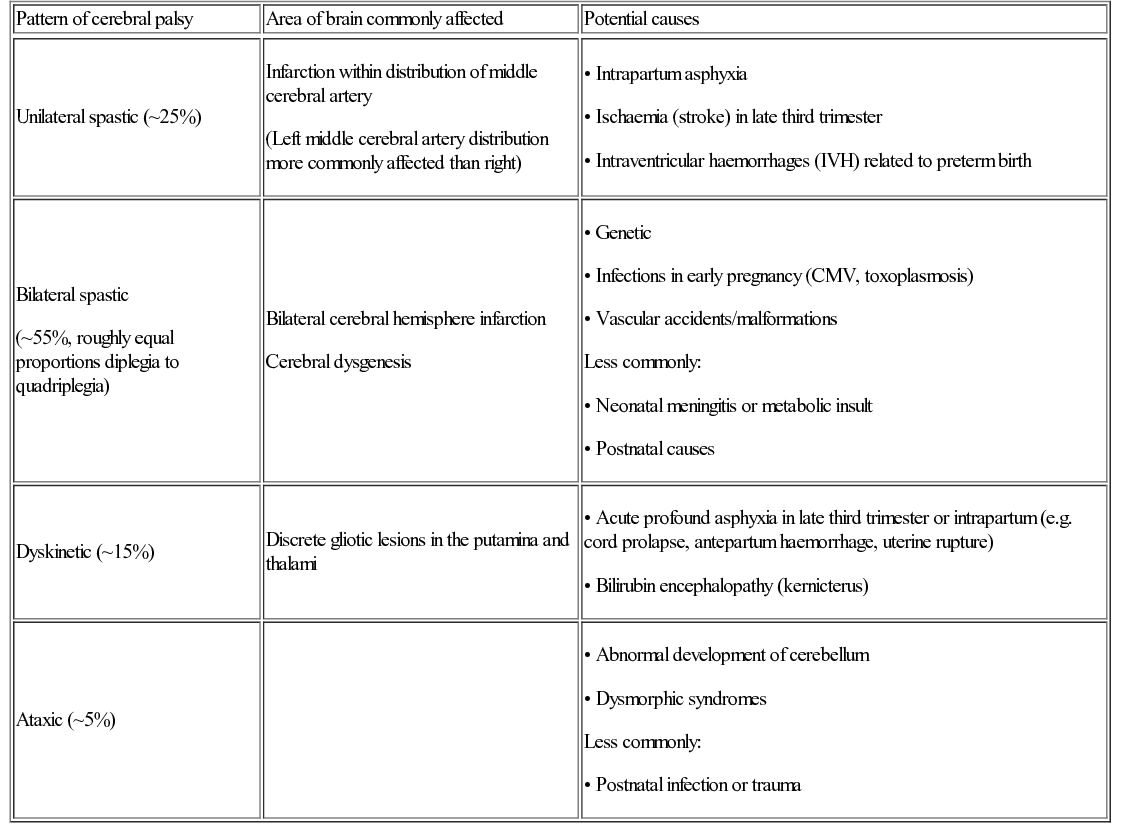

Hayley Griffin, Katherine Martin, Nadya James In the UK, there are 770,000 children under the age of 16 years with a disability. This is about 1 child in 20. In January 2013, 229,390 children in England (2.8% of school-aged children) had a Statement of Special Educational Needs (SSEN), which is a legal document that sets out the special educational help which a child must receive by law. The document is issued by the local education authority (LEA) and is based on the needs, following assessment, of the individual child, drawn up from reports from health services (if applicable) and education. The percentage of children in receipt of an SSEN has remained unchanged for the past five years. Most children (53%) with an SSEN attend a mainstream education setting. Other settings include state-funded special schools (39.6%), independent schools (4.9%), non-maintained special schools (1.8%) and pupil referral units (0.7%). The most common types of need for which children receive an SSEN are moderate or severe learning disability, speech, language and communication needs, behaviour, emotional and social difficulties, and autism spectrum disorders (ASD). The percentage of SSENs issued to children with a physical disability is around 6%, with children with sensory impairments making up another 5%. At the end of 2014, a new system was launched in England for the assessment of a child’s needs. This replaced the SSEN and is called the Education, Health and Care Plan (EHCP). The purpose of this multi-disciplinary assessment is to provide a more holistic view of a child’s needs and includes assessments from health services, education and social care, as well as input from the family and child or young person themselves, before a document detailing a child’s needs in each of these areas is drawn up. The new process is designed to be more rapid, with a target of completion in six months and to have more involvement of the family. Early identification of children with severe or complex needs is required to ensure that early intervention programmes are initiated to offer support to parents and to ensure that a child’s developmental potential is reached. A child with disordered development must be investigated rationally in line with a good clinical history and full physical examination, ensuring that a thorough assessment of the child’s development in all areas is made. There are many potential causes of developmental problems in children, and these may be broadly classified as prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal (Table 5.1). Table 5.1 Potential causes of developmental impairment Genetic Single gene disorders (inherited or new mutation) Chromosomal microduplications or deletions Aneuploidy or tetraploidy Preterm birth 55–60% of children born at 24–25 weeks’ gestation have some degree of impairment, with around 15% having severe impairment (EPICure 2) Infection Meningoencephalitis (viral or bacterial) Toxins Alcohol (fetal alcohol spectrum disorder) Smoking (intrauterine growth restriction) Medication (e.g. valproate and spina bifida) Recreational drugs (e.g. stimulants) Infections Bacterial (e.g. Group B streptococcal or other bacteria) or viral Traumatic brain injury Accidental or non-accidental Drowning Hanging/strangulation Road traffic accidents Conflict related (e.g. war-affected areas) Infections Congenital infection (e.g. toxoplasma, rubella, CMV, etc.) Brain tumour Direct effect or treatment Other Placental insufficiency and growth restriction Intrauterine cerebral arterial or venous infarction Congenital brain malformation (e.g. lissencephaly) Physical Traumatic brain injury Inborn errors of metabolism Impact on development often only after independent of placental support Environmental Inadequate nutrition Psychosocial adversity A great deal of information can be gained from observing the child playing in the clinic room, and it is sometimes of value to observe the child in other settings, such as nursery, school or in the child’s home. Investigation to look for an underlying aetiology informs discussion with parents, identifies treatment opportunities, guides management, and can be helpful for future pregnancies. This section will deal with different presentations of disordered development, subdivided into the broad developmental categories. In reality, however, impairment in one area of development often co-exists with developmental impairment in another area. Children who present predominantly with motor difficulties, and who have an underlying pathology, are usually hypotonic, hypertonic, or have a global learning disability which impairs their intellectual ability to acquire motor skills. Upper motor neuron lesions usually present with hypertonia. The most common disabling condition in children with hypertonia is cerebral palsy, particularly of the spastic and dystonic type, where there is loss of the usual balance of excitatory and inhibitory muscle control. Cerebral palsy is a descriptive term which has been defined as ‘a group of permanent disorders of movement and posture causing activity limitation that are attributed to non-progressive disturbances that occurred in the developing fetal or infant brain. The motor disorders of cerebral palsy are often accompanied by disturbances of sensation, perception, cognition, communication and behaviour, by epilepsy, and by secondary musculoskeletal disorders’. Children with cerebral palsy are not always hypertonic, but there are four main clinical types, some of which have well-described associations with underlying pathologies (Table 5.2). 3. Ataxia: Uncoordinated movements linked to a disturbed sense of balance and depth perception. 4. Choreo-athetoid: Hyperkinesia (excess of involuntary movements). These are often writhing in nature. Table 5.2 Common patterns of cerebral palsy* Infarction within distribution of middle cerebral artery (Left middle cerebral artery distribution more commonly affected than right) Bilateral spastic (~55%, roughly equal proportions diplegia to quadriplegia) Bilateral cerebral hemisphere infarction Cerebral dysgenesis Children with cerebral palsy often have a mixed picture of movements, and this classification does not accurately describe how severely disabled the child is by their movement disorder. The Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) scale is useful as it describes the functional ability of a child’s gross motor skills rather than focusing on the individual type of cerebral palsy. Cerebral palsy can be mimicked by several other conditions and before making a firm diagnosis the differential diagnosis needs to be considered (Table 5.3). Particular care should be taken when there is a ‘family history’ of cerebral palsy to check that there is not an underlying inheritable cause. One must also ensure that a child who presents with ‘ataxic cerebral palsy’ does not have a treatable or definable underlying cause. Meeting the child and family’s complex needs requires a multi-disciplinary team (see below). Here, we will describe some of the drugs and procedures which may be helpful. Specific drug management of spasticity Drugs used in the management of spasticity and their sites of action are shown in Figure 5.1. Diazepam: Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is the principal inhibitory neurotransmitter regulating neuronal excitability in the nervous system. It has a direct effect on muscle tone. Diazepam is a GABA agonist. Due to its central location of action, it relieves spasticity and muscle spasms, but it has additional effects of sedation and acts as an anxiolytic. Long-term use can create dependency, but short-term use can be helpful for painful spasms (for example, after surgery), or to break cycles of distress and increasing spasticity. Baclofen: Baclofen is also a GABA agonist and inhibits neuronal transmission at a spinal level. Its main adverse effect is sedation, which often limits its use. Its passage into the CSF when given orally is poor and high doses are often needed. When used intrathecally, via a surgically implanted continuous-delivery pump, only a tiny fraction of the equivalent oral dose needs to be given. This allows greater efficacy with fewer adverse effects. Tizanidine: Tizanidine is an alpha-2 adrenergic receptor agonist and acts at the spinal level to help relieve spasms. It is particularly useful in children who are severely disabled by cerebral palsy and in those with night-time spasms, as it commonly has a sedative effect. Botulinum toxin A: Botulinum toxin A works by chemically denervating the muscle, allowing the muscle to relax and thus improving function and cosmesis in some cases. It works by cleaving synaptosomal-associated protein (SNAP-25), which is a cytoplasmic protein which aids in the process of attaching the synaptic vesicle to the pre-synaptic membrane. This then stops the release of acetylcholine at the synapse and blocks neurotransmission. The effects gradually wear off (over about 3–6 months) as the myelin sheath retracts and new terminals are made, which form contacts with the myocyte to resume neurotransmission. Dantrolene: Dantrolene works on spasticity and spasms by affecting the calcium uptake into skeletal muscles and decreasing the free intracellular calcium concentration. Sedation is less of a problem with dantrolene than with the other drugs mentioned, but it should be used cautiously as it can cause hepatic dysfunction and blood dyscrasias. Other treatment for spasticity Selective dorsal rhizotomy (SDR): There has been renewed interest in the use of selective dorsal rhizotomy to treat spasticity, particularly in the more mobile groups of children with cerebral palsy (GMFCS levels 2 to 3). This surgical procedure divides some of the lumbar sensory nerve roots, thus interrupting the sensory–motor reflex arc responsible for increased muscle tone. Pre-operative assessment must include bladder assessment due to the risk of affecting continence, and children and families must be counselled about the risks. The child’s general level of gross motor function is unlikely to change significantly, but there may be improvements in quality of gait together with improved comfort and ability to tolerate splints and postural management programme. It is helpful to make a clinical distinction between central hypotonia (affecting predominantly the head and trunk), generalized hypotonia and weakness (affecting all aspects), and peripheral hypotonia (affecting predominantly the limbs). Moderate to severe central hypotonia (other than in a few specific cases) tends to be identified in the neonatal period, where these babies may present with respiratory difficulties, feeding difficulties or as a ‘floppy baby’. Investigations may include: • Microbiological tests (if presenting in neonatal period, to rule out sepsis) • Blood ammonia and lactate levels (inborn errors of metabolism) • Plasma and urine amino acids and urine organic acids (organic acidaemias) • Very long chain fatty acids (peroxisomal disorders) • Microarray-based comparative genomic hybridization (microarray-CGH) Specific disorders to be considered include: aneuploidy (e.g. Down’s syndrome), single gene disorders (e.g. Prader–Willi syndrome), metabolic disorders (e.g. peroxisomal disorders) and structural (e.g. structural brain malformations). We present these below as examples of how these different disorders may present. Down’s syndrome is caused by an additional copy of chromosome 21, either due to non-disjunction (most commonly), by a rearrangement of genetic material, called an unbalanced translocation, where extra genetic material associated with chromosome 21 is inherited, or by mosaicism (see Chapter 9, Genetics). Babies with Down’s syndrome have typical dysmorphic features and are centrally hypotonic. They show delay in all of their developmental milestones and may have initial feeding difficulties. They may have associated congenital anomalies, including heart defects (present in up to 50% of infants). Children with Down’s syndrome will have ongoing additional physical and learning needs throughout childhood and into adulthood. Many newborn children with Down’s syndrome have flaccid muscles and are described as ‘floppy’. In some children, this disappears as the child develops, but many remain in this ‘floppy’ state. There are a few follow-up studies of infants with Down’s syndrome and it seems that this infantile floppiness does improve over time. There is a fairly widespread belief that the children remain with a degree of hypotonia and this state is often invoked as being responsible for much of their delay in motor milestones and impaired motor function. However, this is controversial since there is no proper agreement as to either the exact cause or the definition of hypotonia and there is no consensus as to how to measure it. Some recent studies have shown that the hypotonia seen when children and adults with Down’s syndrome are not moving (i.e. their tendency to have more ‘floppy’ muscles at rest) does not actually impair coordinated movement. The fact that the muscles are floppy at rest suggests there may be some peripheral component to the observed hypotonia. Prader–Willi syndrome is caused by a deletion on the long arm of the paternally inherited chromosome (15q13) in 70% of cases, or due to maternal uniparental disomy (25%). The remaining 5% are due to an imprinting defect, and only this form carries an increased risk for future pregnancy. Prader–Willi syndrome should be considered in babies with feeding difficulties, those requiring nasogastric tube feeding, sticky saliva, extreme hypokinesia and a combination of central hypotonia and limb dystonia. Children with Prader–Willi syndrome also have distinctive facial characteristics and other dysmorphic features. Despite initial poor feeding, children with Prader–Willi syndrome begin to show increased appetite as they grow. This can lead to excessive eating (hyperphagia) and life-threatening obesity. They also have hypogonadism, causing immature development of sexual organs and delay in puberty. Learning disabilities can be severe. They tend to be particularly impaired in their emotional and social development. Peroxisomes are spherical organelles within cells containing important oxidative and other enzymes. Babies with peroxisomal disorders tend to present with extreme hypotonia of the neck in the context of general neonatal hypotonia. Peroxisomal disorders can be divided into two categories: Measurement of very long chain fatty acids may detect some peroxisomal disorders, but there is no ‘metabolic screen’ which will detect all of them. Results must be correlated with clinical findings. Particular clinical features which should be sought where a peroxisomal disorder is suspected in a hypotonic child include: Suspicion of a peroxisomal disorder should be present where a school-age boy shows developmental regression in the context of previously normal development (although there may be a number of other causes for this) and in older girls with spastic paraplegia.

Developmental problems and the child with special needs

Definition and numbers

Causes of developmental problems

Prenatal

Perinatal

Postnatal

Hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy

Note: 75–80% of cases of cerebral palsy are due to antenatal events rather than injury occurring around the time of birth

The clinical manifestations of disordered development

Gross motor development

Upper motor neuron lesions

Cerebral palsy

Pattern of cerebral palsy

Area of brain commonly affected

Potential causes

Unilateral spastic (~25%)

Dyskinetic (~15%)

Discrete gliotic lesions in the putamina and thalami

Ataxic (~5%)

Management of cerebral palsy

Central hypotonia

Down’s syndrome

Prader–Willi syndrome

Peroxisomal disorders

Brain malformations

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Developmental problems and the child with special needs

Chapter 5

Learning objectives

By the end of this chapter the reader should: