FIGURE 39-1 AP radiographs of the right and left shoulder in an 11-year-old right-handed youth baseball pitcher demonstrating physeal widening and juxtaphyseal sclerosis of the symptomatic right side.

Previous biomechanical analyses have demonstrated that external rotation torques approximate 18 Nm during pitching, 400% of the mechanical tolerance of physeal cartilage. Distraction forces may be as high as 200 Nm in the adolescent shoulder, representing 5% of the physeal cartilage strength.13,14 These forces are thought to be highest during the late cocking to late release phases of the pitching motion. It has been hypothesized that these rotational and tensile forces cause “microfractures” across the physeal zone of hypertrophy, which may be vulnerable to greater injury due to the orientation of the collagen fibers and relatively low mechanical strength.15,16

Not surprisingly, this condition is most commonly seen in skeletally immature athletes between the ages of 9 and 15, at a time in which the physis is metabolically active and vulnerable to injury. Additional risk factors include arm pain and fatigue during pitching, pitch counts of higher than 80 per game, and pitching over more than 8 months per calendar year.17

Clinical Presentation and Evaluation

Patients will typically present with insidious onset shoulder pain, exacerbated during and after throwing. The pain is usually localized to the anterior and lateral aspect of the shoulder, and there is often tenderness to percussion and deep palpation of the proximal humerus. Abduction and forward flexion motion and strength are frequently unaffected but may be limited at the time of presentation due to pain.

Careful examination of internal and external rotation will often demonstrate greater external rotation and less internal rotation than the unaffected, nonthrowing shoulder, the so-called glenohumeral internal rotation deficit (GIRD).18–22 Unlike older adults, it should be noted that young overhead athletes may often have GIRD without an associated increase in external rotation.18 Care should be made during assessment of shoulder rotation to prevent scapular elevation and protraction, which is typically recruited to compensate for loss of glenohumeral joint internal rotation. This may lead to scapulothoracic dyskinesis and asymmetric scapulothoracic motion during shoulder range-of-motion testing. If the GIRD and/or scapulothoracic dyskinesis are severe, provocative testing for internal impingement and superior labral/long head of biceps pathology may be positive.

Radiographic Evaluation

Plain radiographs of the shoulder should be examined in patients with significant pain and tenderness, even in the absence of an obvious traumatic event. Standard anteroposterior (AP), scapular Y, and axillary views are sufficient, though an AP in external rotation may allow for better visualization of the undulating proximal humeral physis. Characteristic findings consistent with epiphysiolysis include physeal widening, cystic changes, juxtaphyseal sclerosis, or periosteal reaction.23 As these findings are often subtle and difficult to distinguish from the normal physis, contralateral comparison radiographs are helpful (Figure 39-1).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may assist in diagnosis, particularly in cases where plain radiographs appear normal. Physeal widening and abnormal signal within the juxtaphyseal-metaphyseal region may be seen.24–26

Treatment

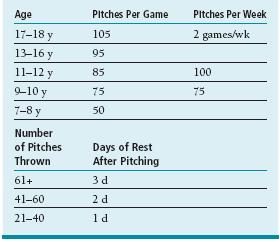

As with all overuse sporting injuries, prevention remains the key to treatment. For youth baseball pitchers, a number of formal guidelines have been developed to regulate the quantity and quality of throwing allowed to young throwers (Tables 39.1 and 39.2). Derived from epidemiological data of shoulder injuries in youth throwers and formulated by a consensus of baseball and medical experts, these guidelines attempt to minimize the risk of overuse injury.27,28

Table 39.1

Youth baseball pitching guidelines

Table 39.2

Age at which pitches should be learned

In addition to rules and guidelines, efforts should be made to educate young throwers on proper pitching mechanics, appropriate warm-up and cool-down activities, and pertinent stretching and strengthening regimens to avoid injury due to mechanical failure.

However, further work needs to be done. Guidelines are helpful and applicable to the general population, yet to date they are mostly based upon chronological age rather than physiological status. (While some 12-year-olds are shaving, others have yet to begin their preadolescent growth spurt.) In addition, there is little oversight and monitoring of athletes involved with multiple teams in multiple leagues during the same season, an increasingly common phenomenon in today’s highly competitive climate. Furthermore, though great attention has been paid to youth baseball pitchers, little scientific information exists on the risks and recommendations for other position players or other overhead sports (e.g., softball, tennis). Finally, in the era of specialization and earlier sports participation, better guidelines need to be created regarding the optimal time spent away from throwing and baseball between seasons.

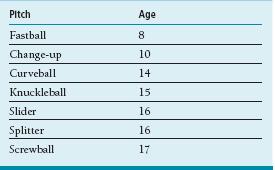

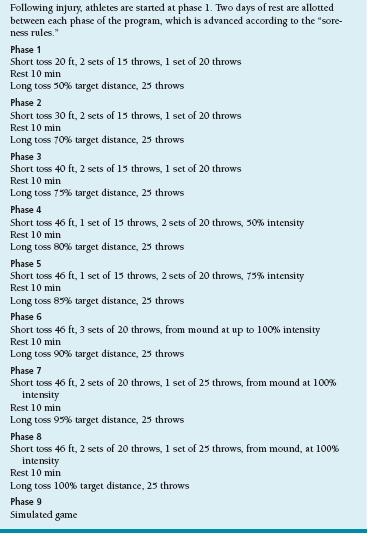

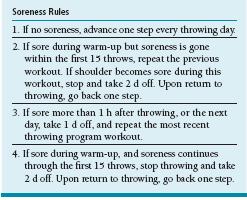

In patients with established proximal humeral physeal stress injury, treatment is predicated on rest until there is resolution of pain and tenderness. While highly variable, this typically involves cessation of all throwing activities for 6 to 12 weeks. After the acute pain—and presumably physeal stress injury—has resolved, physical therapy is initiated for range of motion and strengthening. Particular attention is given to “sleeper stretches” to improve internal rotation and periscapular strengthening to address scapulothoracic dyskinesis, hyperangulation, and internal impingement. Advancement to an interval throwing program with attention to pitching mechanics is then begun, adhering to the “soreness rules”23,29,30 (Tables 39.3 and 39.4). Patients and families should be counseled that this process is dynamic and may indeed take months to complete.

Table 39.3

Interval throwing program for youth baseball (age 10–12 y)

Adapted from Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L, Konin JG, et al. Development of a distance-based interval throwing program for Little League-aged athletes. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24:594–602 and Axe MJ, Wickham R, Snyder-Mackler L. Data-Based Interval Throwing Programs for Little League, High School, College, and Professional Baseball Pitchers. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2001;9:24–34.

Adapted from Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L, Konin JG, et al. Development of a distance-based interval throwing program for Little League-aged athletes. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24:594–602 and Axe MJ, Wickham R, Snyder-Mackler L. Data-Based Interval Throwing Programs for Little League, High School, College, and Professional Baseball Pitchers. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2001;9:24–34.

ELBOW: MEDIAL EPICONDYLE APOPHYSITIS

Elbow pain is an equally common complaint in the young athlete. As described earlier, previous longitudinal studies of youth baseball pitchers have demonstrated that 26% will develop elbow pain in-season.11 Elbow pain is not limited to the pitcher or thrower, however. Repetitive stress and overuse will cause elbow pain and functional limitations in a host of athletes, including gymnasts, tennis and other racquet sports players, wrestlers, and football players, among others.

Medial elbow pain is particularly prevalent, due to the valgus stresses imparted on the elbow during overhead and weight-bearing activities. In addition, there is repetitive eccentric loading of the flexor-pronator mass during many sports. These tensile forces on the medial elbow will often result in a stress injury of the medial epicondylar apophysis, which is the “weak link” in the chain of medial-sided structures (ulna, ulnar collateral ligament, medial epicondyle, medial epicondylar apophysis, and distal humerus). Repetitive submaximal stress may result in mechanical failure and apophyseal widening. Medial epicondylar avulsion fractures may be seen in athletes resulting from high-energy injuries, particularly in the setting of repetitive overuse and an already weakened apophysis.

Clinical Presentation and Evaluation

Patients will typically present with medial elbow pain, localized to the medial epicondyle and flexor-pronator origin. Pain occurs during and/or after sports activities such as throwing. The patient’s history should be carefully obtained, not only to assess the character of the pain but also to get information regarding the inciting activities. In the young thrower, questions are asked regarding the number, frequency, and types of pitches thrown.

Direct palpation of these structures will elicit tenderness, and occasionally swelling is present. In rare situations, there may be objective signs of ulnar nerve irritation about the cubital tunnel. Valgus stress testing may elicit pain but rarely demonstrates frank instability. Careful examination of elbow motion will reveal full motion or subtle elbow flexion contractures.

As this condition is often seen in throwers, careful examination of the rest of the kinetic chain is critical.31 Evaluation of the shoulder will often reveal scapulothoracic dyskinesis or asymmetry and GIRD. Identification of these additional features and education of the athletes and families regarding their significance is critical to ensure adequate comprehension of the scope of the problem and treatment.

Radiographic Evaluation

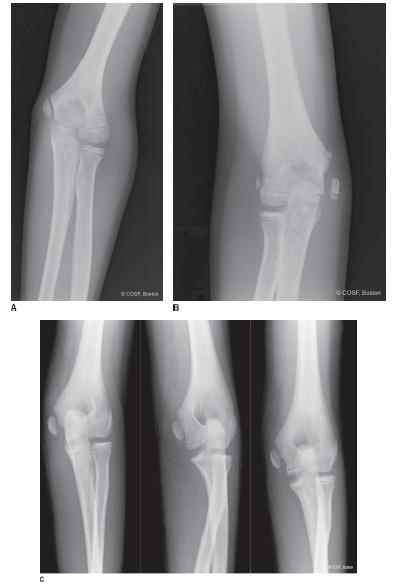

Standard AP and lateral radiographs of the elbow are obtained to assess the morphology of the medial epicondyle. Oblique views put the medial epicondyle in profile. Comparison views of the unaffected contralateral elbow are helpful to distinguish subtle irregularities. Findings include widening of the medial epicondylar apophysis, with both acute and chronic features (Figure 39-2). In cases in which ulnar collateral ligament insufficiency is suspected, a gravity stress radiograph may be performed. This is taken with the patient supine, shoulder abducted 90 degrees, elbow extended, and forearm supinated. An AP x-ray of the elbow is taken by directing the beam parallel to the floor. Gravity provides a mild valgus stress, which results in medial joint space widening of >3 mm.

FIGURE 39-2 Radiographs of medial epicondylar apophysitis. A: Mild widening in a 10-year-old baseball pitcher with medial elbow pain and bony tenderness. B: Widening and displacement in a former pitcher with persistent pain, ulnar nerve symptoms, and mild valgus instability. C: Acute or chronic injury with a displaced medial epicondyle fracture sustained during gymnastics in a 10-year-old female.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree