Ovarian Tumors Complicating Pregnancy

Jack Basil

Kristin Coppage

James Pavelka

DEFINITIONS

Hyperreactio luteinalis—A benign, frequently large (15 to 20 cm), usually bilateral ovarian enlargement caused by an increased sensitivity to human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG). These masses are composed of numerous luteinized follicular cysts and are more common in conditions in which the hCG is increased (e.g., hydatidiform mole, multiple gestation). This condition is benign and resolves spontaneously after pregnancy.

Luteoma of pregnancy—A benign neoplasm of the ovary caused by the hormonal effects of pregnancy. It is usually solid and unilateral. It is most often asymptomatic and found incidentally. It may cause virilization and complications if torsion occurs. It resolves spontaneously after pregnancy.

Pulsatility index (PI)—An arterial waveform index that has been shown to be useful in discriminating benign from malignant adnexal masses. A PI > 1.0 is almost always associated with a benign mass. A PI < 1.0 is suggestive of malignancy but can be seen in a corpus luteum cyst or an inflammatory mass.

The coexistence of an adnexal mass with pregnancy presents problems to both the clinician and the patient, the most serious being that of malignancy. The care of the patient must balance the competing risks and benefits of the mother and fetus. Through a multidisciplinary approach of specialists in gynecologic oncology, maternal fetal medicine, pathology, and neonatology, the best plan of action, observation versus intervention, can be determined. Therapeutic implications including loss of the current pregnancy and loss of future fertility result in an emotionally charged environment, which must be skillfully navigated by all members of the health care team.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Cancer complicates 1:1,000 pregnancies in the United States. The most common malignancies seen in pregnancy include malignant melanoma (2.6:1,000), Hodgkin lymphoma (1:1,000-6,000), breast cancer (1:3,000-10,000), cervical cancer (1.2:10,000), ovarian cancer (1:10,000-100,000), colorectal cancer (1:13,000), and leukemias (1:75,000-100,000).

The lifetime risk of developing ovarian cancer is 1.4% (14 per 1,000), the highest risk occurring after menopause. Women of reproductive age have a low risk approximating 0.2% to 0.4%. Benign ovarian tumors are the most common complicating pregnancy. The exact incidence, however, depends on whether one considers simple cysts noted on ultrasound examination (1 in 50 live births), during pelvic examination (1in 80 live births), or those that ultimately require laparotomy (1 in 1,000 to 1 in 1,500 live births). Hill and colleagues reported findings for ovarian cysts found at the time of secondand third-trimester ultrasound. Ovarian cysts were diagnosed in 4.1% of second- or third-trimester ultrasounds. Most of these cysts were less than 3 cm and resolved spontaneously. Eighteen of the 7,996 patients had an exploratory laparotomy, which was equivalent to one surgery in 444 deliveries. All of these lesions were benign on pathologic examination. Ueda and Ueki reported 106 patients who required ovarian surgery during pregnancy. Of these patients, 31 (29.2%) had physiologic ovarian cysts, 70 (66%) were benign tumors, and 5 (4.7%) were malignant. More recent observations by Schlemer et al. have noted that adnexal masses greater than 5 cm were observed in 63 patients (0.05%), with 4 patients (6.8% of masses and 0.0032% of deliveries) diagnosed as malignant. Finally, these tumors may also be an incidental finding at the time of cesarean. Koonings and colleagues noted the incidence of ovarian tumors complicating cesarean section to be about 1 in 200 cesarean births. Dede et al. also observed a 0.8% incidence of masses greater than 5 cm at the time of cesarean section.

DIAGNOSIS

The definitive diagnosis of an ovarian tumor can only be made by pathologic examination. This places the clinician in a difficult dilemma during pregnancy. Until the widespread use of ultrasound, ovarian masses often remained unrecognized, as their symptoms frequently mimic common symptoms of pregnancy. Over time, clinicians have realized that there are windows of opportunity to evaluate the adnexa. These include the initial pelvic examination in the first trimester (palpable masses), any ultrasound performed, and careful evaluation at the time of operative intervention (cesarean section or postpartum tubal ligation). A thorough pelvic examination at the time of termination of pregnancy is another opportunity to evaluate the ovaries.

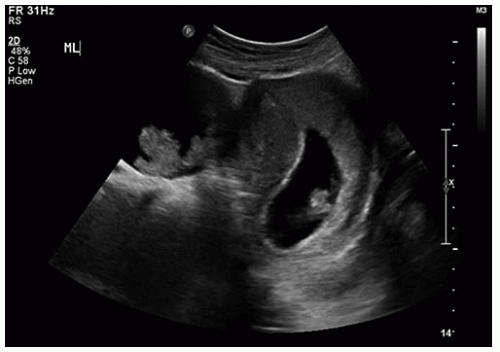

The increasing (nearly routine) use of ultrasound examination in pregnancy affords an excellent opportunity for the diagnosis of coexistent ovarian pathology; it is for this reason that such an examination should always include the adnexa (Fig. 35B.1). The results of ultrasound, although potentially very useful in the relatively rare patient with an ovarian malignancy, may create a difficult dilemma for the clinician who must decide how to proceed when an ovarian cyst is diagnosed in pregnancy. Perkins and coworkers evaluated 1,001 patients with first-trimester ultrasound and determined that a simple ovarian cyst was seen in 29% of these patients. The incidence of ovarian cysts decreased after 8 weeks, and absence of a cyst was more often associated with blighted ovum.

Bromley and Benacerraf evaluated the accuracy of sonographic diagnosis of adnexal masses during pregnancy. They evaluated all patients with an adnexal mass measuring 4 cm or greater noted beyond 12 weeks gestation. One hundred and thirty-one lesions were noted; of these, 89.3% were accurately diagnosed as benign. Fourteen of the 131 lesions (10.7%) had sonographic characteristics of malignancy. One of 14 (7%) of these patients had ovarian cancer, for a 0.8% malignancy rate in this study. Lavery and colleagues, in a review of 3,918 ultrasound examinations at 20 weeks gestation, noted cyst formation greater than 2 cm in 2.4% of examinations. Only nine patients (0.23%) required surgical intervention. Hogston and Lifford, in a review of 26,000 patients who received routine ultrasound, noted an incidence of cyst formation of 0.52%. All complex cysts and those greater than 6 cm were operated on primarily (10%). Eighty-five percent of the remaining patients who were followed conservatively showed spontaneous resolution, with the exception of 5 patients who ultimately required laparotomy.

Doppler sonography has been evaluated for use in complex adnexal masses in pregnancy. Wheeler and Fleischer evaluated 34 pregnant patients with complex adnexal masses. Diagnosis made by color Doppler sonography was compared with actual histopathologic diagnosis. Three malignant and five low malignant potential tumors were correctly identified with a sensitivity of 0.89 and a mean pulsatility index (PI) of 0.71. The mean PI for benign lesions was greater than 1, and the negative predictive value for PI > 1 was 0.93. The positive predictive value for PI < 1 was 0.42, indicating that some benign lesions were incorrectly classified as malignant when a PI < 1 is used as a cutoff for possibly malignant tumors. However, color Doppler appears to be highly predictive of a benign lesion when the PI is greater than 1.

FIGURE 35B.1 This is a midline picture from a first-trimester ultrasound. Both the intrauterine pregnancy on the right and maternal adnexal mass on the left are visualized. |

Epithelial tumor markers such as CA-125, CEA, CA-19-9, and CA-15-3 demonstrate some fluctuation during pregnancy and should be interpreted with caution. However, median levels are still typically within established norms for premenopausal women. Alpha-fetoprotein levels rise during pregnancy. High MSAFP (maternal serum alpha fetoprotein) levels can be seen with germ cell tumors. These levels are significantly higher (MoM of 24) than are those seen in neural tube defects or abdominal wall defects as shown in a study by Elit and colleagues. Alpha-fetoprotein is heterogeneous, and the yolk sac variant can be separated by affinity chromatography to determine if the elevation is due to the yolk sac or liver variant. Another chemical marker is LDH (lactate dehydrogenase). Ovarian dysgerminomas may have significantly elevated levels of LDH in pregnancy as shown by Buller and colleagues. Pregnancy LDH is usually in normal range unless preeclampsia/HELLP syndrome has been diagnosed. Inhibin is a chemical made by the placenta and can be used to assess risk for chromosomal anomalies. Therefore, inhibin cannot be used during pregnancy to help to diagnose cell tumors, as it does in a nonpregnant patient. Finally, human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) is used to follow some germ cell tumors such as choriocarcinoma; however, it again is not useful in pregnancy. Composite tests, such as the newer OVA-1 test, have no established data in pregnant women; include components such as transferrin, which are altered in pregnancy; and are therefore not recommended.

From a treatment standpoint, the first trimester is clearly the best time to diagnose an adnexal mass complicating pregnancy. Because tumors are rarely symptomatic during this period, most such tumors are discovered by ultrasound examination. With the increasing incidence of ultrasound evaluation and use of cesarean section, recent articles suggest that only about 50% of ovarian tumors complicating pregnancy are symptomatic. When symptomatic, the patient typically presents with abdominal pain, abdominal distention, and vague gastrointestinal symptoms. All these symptoms can be directly attributable to pregnancy itself; therefore, it is not surprising that most pregnant women with these symptoms are not evaluated for an ovarian tumor.

A successful outcome for both mother and fetus depends on a high index of suspicion with early diagnosis. One should consider an ovarian mass in any woman who experiences abdominal pain in pregnancy. Furthermore, torsion, rupture, infection, or hemorrhage of an ovarian tumor should be included in the differential diagnosis of any catastrophic abdominal obstetric event. This is particularly true during times of rapid change in uterine size or position (e.g., 8 to 16 weeks), during termination of pregnancy, during labor and delivery, or in the immediate postpartum period.

The incidence of torsion complicating an ovarian tumor in the nonpregnant state is about 2%. Torsion complicating an ovarian tumor during pregnancy is much higher. One report by Ueda and Ueki showed a 21.8% rate of torsion in ovarian tumors in pregnancy. Further, it is clear that the previously unrecognized symptomatic ovarian tumor complicating pregnancy can become catastrophic. Wang and colleagues retrospectively evaluated 174 patients who underwent surgery for ovarian masses during pregnancy. These patients were divided into two groups: those with emergency surgery (32 patients) and those with elective surgery (142 patients). They found in the emergency surgery group that half of the surgeries occurred in the first trimester, they contributed to 75% of total fetal wastage and 87% of spontaneous fetal loss, and tumor sizes were significantly larger. In their experience, tumors less than 5 cm in size never caused symptoms requiring surgery. Therefore, size of tumor, ultrasound characteristics, color Doppler flow, serum analytes, and symptoms are important in determining the management of pregnant patients with adnexal masses.

PATHOLOGY

Benign neoplasms complicating pregnancy include two tumorlike conditions with which every gynecologist should be familiar. Hyperreactio luteinalis (first described by Burger in 1938 as a grossly multicystic, usually bilateral ovarian enlargement, often 15 to 20 cm in size) is a term used to describe numerous luteinized follicular cysts of the ovary complicating pregnancy. Microscopically, one notes extensive luteinization of the theca and granulosa cell layers. Bradshaw and associates suggest that the hyperandrogenicity seen in this condition is related to increased ovarian sensitivity to hCG. Therefore, it is seen in conditions in which the hCG is elevated, such as hydatidiform mole, multiple gestations, choriocarcinoma, and erythroblastosis fetalis. Hyperreactio luteinalis also has been associated with normal pregnancy, and, in these patients, it has not been associated with fetal virilization. These tumors spontaneously regress after delivery but may take up to 6 months to resolve. Hyperreactio luteinalis also may occur in subsequent pregnancies.

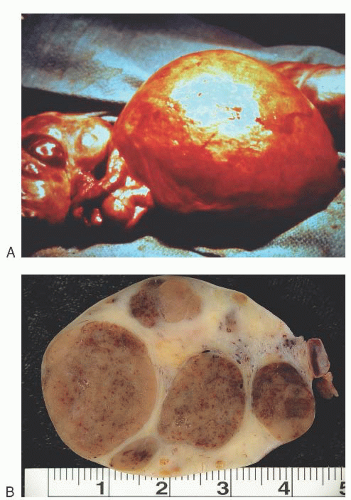

Luteoma of pregnancy is a specific benign, usually unilateral, solid lutein cell tumor of the ovary found in late pregnancy, often noted at cesarean section (Fig. 35B.2A, B). First described by Sternberg in 1966, this tumor is grossly bosselated, soft, fleshy, yellow, or hemorrhagic. Microscopically, it exhibits an acidophilic granular cytoplasm with sparse lipid formation and a distinctive reticular pattern. It is likely the most common cause of maternal virilization during pregnancy. The etiology is unknown, but theories have included luteinized stromal cells present before pregnancy that respond to hCG or “hyperluteinized” theca cells, granulosa cells, or a combination of the two. Fifty percent of female infants born to virilized mothers with pregnancy luteoma exhibit signs of virilization.

The important clinical implication with both of these lesions is that if they are recognized or suspected, simple biopsy without further surgery is adequate therapy, because both invariably resolve spontaneously.

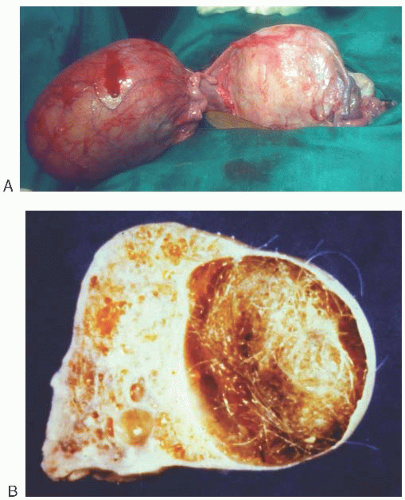

The most common benign neoplasm of the ovary in pregnancy is the benign cystic teratoma, which accounts for about one third of all benign ovarian tumors seen in pregnancy (Fig. 35B.3A, B). The second most common group of ovarian tumors complicating pregnancy is that of cystadenomas (Fig. 35B.4). These represent about 15% of tumors. Endometriomas, simple cysts, corpus luteal cysts, tubal cysts, myomas, and other miscellaneous lesions constitute the remaining types of tumors seen in pregnancy (Table 35B.1).

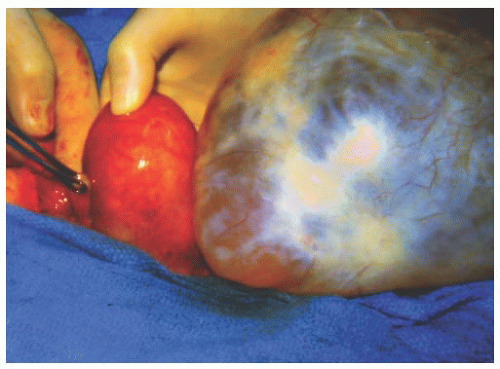

Malignant ovarian tumors constitute only about 1% to 2% of all adnexal masses that complicate pregnancy and require

surgical exploration. The single most common malignant ovarian tumor complicating pregnancy probably is dysgerminoma. Malignant tumors of epithelial origin as a group, however, are more common (Fig. 35B.5); tumors of low malignant potential occur most frequently (Fig. 35B.6). Sex-cord stromal tumors are the third most common primary malignant ovarian neoplasms, representing about 17% to 20% of such tumors. Krukenberg and other metastatic tumors represent about 12% to 13% of malignant ovarian neoplasms complicating pregnancy (Fig. 35B.7).

surgical exploration. The single most common malignant ovarian tumor complicating pregnancy probably is dysgerminoma. Malignant tumors of epithelial origin as a group, however, are more common (Fig. 35B.5); tumors of low malignant potential occur most frequently (Fig. 35B.6). Sex-cord stromal tumors are the third most common primary malignant ovarian neoplasms, representing about 17% to 20% of such tumors. Krukenberg and other metastatic tumors represent about 12% to 13% of malignant ovarian neoplasms complicating pregnancy (Fig. 35B.7).

Whether malignant or benign, most ovarian tumors complicating pregnancy are unilateral. Karlen and associates reported 90% of dysgerminomas in pregnancy to be unilateral, and Young and colleagues reported 35 of 36 sex-cord stromal tumors to be unilateral when complicating pregnancy. Even malignant tumors of epithelial origin noted during pregnancy are unilateral in 90% of cases. The rarer germ cell tumors, such as endodermal sinus tumors, virtually always are unilateral as well. It is also interesting that most bilateral tumors occurring in pregnancy are not malignant; these include benign cystic teratoma, endometriosis, and hyperreactio luteinalis. The most common bilateral malignant ovarian tumors are the metastatic Krukenberg types. Somewhat less common are primary malignant tumors of epithelial origin.

TABLE 35B.1 Pathology of Pelvic Masses Complicating Pregnancy | |

|---|---|