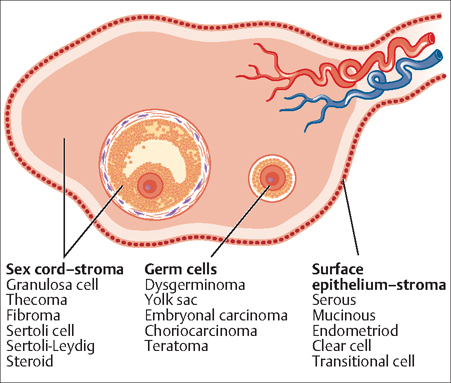

51 Ovarian and Fallopian Tube Cysts and Tumors Robert L. Barbieri One of the common problems in gynecology is determining the optimal approach to the management of an adnexal or ovarian cyst or tumor. The term “adnexal” refers to both the fallopian tube and ovary and the connective structures immediately adjacent, including the upper portion of the broad ligament and mesosalpinx. It is often difficult to definitively determine if an adnexal lesion arises in the fallopian tube or ovary until surgical exploration. Consequently, “adnexal” is ordinarily used to indicate ambiguity about the structure causing the cyst or tumor. The point prevalence of an ovarian cyst or tumor is about 8% in premenopausal women and 2% in postmenopausal women. Surgical exploration and cyst or tumor removal are required if there is a suspicion of malignancy. Central to the problem is using available data to make an estimate of the likelihood that a tumor is benign or malignant. In general, three factors guide the management of an adnexal or ovarian mass: the menopausal status of the patient; the appearance of the ovarian cyst or tumor on ultrasound imaging; and a serum CA-125 measurement. Many different ovarian structures can give rise to cysts and tumors (Fig. 51.1). The approach to an ovarian cyst or tumor varies for premenopausal and postmenopausal women. In premenopausal women the differential diagnosis is very broad (Table 51.1) and ultrasonography plays the key role in determining whether the tumor is benign or malignant, and whether the tumor requires surgery. Ultrasonographic findings which suggest that a malignant tumor is present include: a solid tumor with irregular borders; ascites; four or more papillary structures in the cyst or tumor; diameter greater than 10 cm; and Doppler demonstration of significant blood flow into the cyst or tumor. Ultrasonographic findings which suggest that an ovarian cyst is benign include: a unilocular cyst; no solid component greater than 0.7 cm in diameter; smooth cyst or tumor surfaces; and Doppler demonstration of no significant blood flow into the cyst or tumor. In premenopausal women the most commonly detected adnexal cyst is a functional ovarian cyst, which arises from the normal process of ovarian follicular growth, ovulation, and corpus luteum formation. The epithelium lining of an ovarian follicular cyst has basal tight junctions that permit the epithelium to secrete fluid into the closed space, permitting the cyst to grow. Most follicular cysts resolve over one or two months and can be followed to resolution using pelvic ultrasound examination. In postmenopausal women, ultrasonography plus measurement of serum CA-125 play the key role in assessing whether the tumor is malignant. In postmenopausal women with an ovarian cyst or tumor, a CA-125 level equal to or greater than 35 IU/L suggests the presence of an ovarian or fallopian tube malignancy. In premenopausal women the CA-125 level is often elevated due to benign pelvic diseases such as endometriosis or fibroid tumors. Consequently, in premenopausal women the CA-125 measurement is not specific for the diagnosis of ovarian malignancy. CA-125 is much more sensitive and specific for the diagnosis of ovarian malignancy in postmenopausal women, in whom a CA-125 level greater than 100 IU/L strongly suggests the presence of an ovarian malignancy. Many authorities recommend that a postmenopausal woman with an ovarian cyst or tumor and a CA-125 level greater than 100 IU/L should be immediately referred to a gynecologic oncologist, so that cytoreductive surgery can be accomplished, if necessary, at the initial surgery. Fig. 51.1 The myriad of ovarian tumor histological subtypes are derived from the surface epithelium-stroma, germ cells, or sex cord-stromal elements Adapted from Up To Date — Origins of ovarian tumors.

Ovarian Tumors

Evaluation of the Adnexal or Ovarian Mass

| Processes arising from the ovary |

| Simple follicular cysts |

| Corpus luteum cysts |

| Hemorrhagic cysts |

| Polycystic ovary syndrome |

| Theca lutein cysts |

| Endometrioma |

| Sex cord stromal tumors |

Germ cell tumors

|

Ovarian epithelial tumors

|

| Processes arising from outside the ovary |

| Hydrosalpinx |

| Paraovarian cyst |

| Peritoneal inclusion cyst |

| Ectopic pregnancy |

| Pedunculated fibroid |

| Diverticular abscess |

| Colon cancer |

| Fallopian tube cancer |

| Inflammatory bowel disease |

| Pancreatic pseudocyst |

| Pelvic kidney |

Ovarian Torsion

Ovarian torsion involves the twisting of the ovary around its pedicle causing a reduction or cessation in blood flow to the ovary, which incites severe lower abdominal pain, nausea, and pelvic tenderness. Ovarian torsion is a common gynecologic emergency. The presentation is non-pecific with both severe abdominal/pelvic pain and an adnexal mass being present in over 85% of women with torsion. Laparoscopy is required to definitively diagnose or exclude ovarian torsion. When the diagnosis of ovarian torsion is raised in a woman with lower abdominal/pelvic pain and an ovarian or fallopian tube cyst, laparoscopy is required to confirm that the diagnosis is correct. If blood flow to the ovary has ceased, all ovarian tissue on the affected side may die within 12 hours unless the ovary and vascular pedicle are untwisted at surgery.

Epithelial Ovarian Tumors

Ovarian Tumors of Low Malignant Potential

Ovarian tumors of low malignant potential (also known as borderline tumors) have two common histological patterns: serous (histology similar to the fallopian tube), or mucinous (histology similar to the cervix glands). Ovarian tumors of low malignant potential are often unilateral and stage I or II at the time of diagnosis and surgical treatment. Conservative surgical approaches with preservation of fertility can be achieved by performing a unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and staging, thereby conserving the contralateral ovary and uterus. Chemotherapy does not play a significant role in the treatment of these tumors.

Ovarian Epithelial Cancer

Ovarian cancer is the most common gynecologic malignancy that causes death. Following breast, lung, and colon cancer, it is the fourth most common cause of cancer death in women living in developed countries. Of all cancer deaths in women, about 6% are due to ovarian cancer. Ninety percent of ovarian tumors are epithelial, consisting of five histological subtypes: serous, mucinous, endometrioid, clear cell, or transitional cell. These histological types recapitulate the development of the müllerian tract:

- The serous histology best resembles the epithelium of the fallopian tube.

- The mucinous histology best resembles the epithelium of the cervix.

- The endometrioid histology resembles the endometrium.

- The clear cell histology resembles the pelvic peritoneum.

Most cases of ovarian epithelial cancer (OEC) are diagnosed in women between 40 and 65 years of age.

Epidemiology: The lifetime risk of developing OEC is 1.5%. Most women with OEC will die of the disease. Repetitive ovulation and stimulation by gonadotropins are two proposed mechanisms which link various reproductive exposures and the risk of ovarian cancer. Exposures that reduce the risk of developing OEC include:

- prolonged use of estrogen-progestin contraceptives

- multiparity

- tubal ligation

- prolonged intervals of breast-feeding

Exposures and diseases that increase the risk of OEC include:

- infertility and nulliparity

- early menarche or late menopause

- endometriosis

- exposure to talc

Germ-line mutations in BRCA1, BRCA2 and the DNA repair genes (MSH2, MLH1, PMS1) are associated with an increased risk of ovarian cancer. Interestingly recent pathological studies suggest that in women with BRCA1 mutations, ovarian cancer lesions actually begin in the distal fallopian tube and then spread to the ovary and other peritoneal surfaces (see Chapter 45).

History and physical examination: OEC is a “silent” killer. It is often very difficult to diagnose OEC prior to its reaching an advanced stage (stage III or IV). Most medical organizations recommend against screening in the general population. But recent recommendations are to be vigilant about early symptoms of ovarian cancer to pursue early detection. The six symptoms that are most highly and reliably associated with a diagnosis of ovarian cancer are pelvic pain, abdominal pain, increased abdominal circumference, abdominal bloating, early satiety, and difficulty eating. Up to 70% of women with ovarian cancer report these symptoms for up to a year before their cancer diagnosis. If these symptoms occur at least 12 days a month, investigations including physical examination, CA-125 testing, and pelvic sonography may be warranted.

Physical examination using bimanual pelvic examination to detect an ovarian tumor has low sensitivity and specificity. In overweight and obese women it is unusual to palpate an adnexal mass on bimanual examination, even if a large cystic structure is demonstrated on ultrasound imaging (low sensitivity). In thin, premenopausal women, it is usual to palpate an ovary, but unless the ovary is significantly enlarged (>5 cm) it is unlikely to represent an ovarian tumor. In postmenopausal women, all palpated adnexal masses should be evaluated with a pelvic ultrasound exam and CA-125 measurement. For premenopausal women with an adnexal mass palpated on bimanual pelvic examination, pelvic ultrasonography is usually warranted.

Pelvic ultrasonography and CA-125 measurement:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree