Outcomes of Preterm and Term Infants

Marilee C. Allen

All infants are at risk for adverse outcomes, but the risk is far higher for infants that require neonatal intensive care. Most of the conditions that place a neonate at risk of dying also increase the risk of subsequent health and neurodevelopmental problems. Over the last half century, major advances in high-risk obstetrics and neonatal intensive care have yielded dramatic reductions in neonatal mortality at all gestational ages.1,2 There has been no concomitant dramatic reduction in frequency of health problems or neurodevelopmental disabilities. Since no one can foresee the future for an individual infant, prediction of outcome relies on assessment of the infant’s current status (eg, neuroimaging and examination findings) as well as prenatal, perinatal, and neonatal risk factors, illnesses, and treatments.3,4

Maturation of the central nervous system (CNS) is a dynamic process. Successive stages of neuromaturation have been described in the fetus, preterm infant in a neonatal intensive care unit, preterm infant at term, full-term neonate, infant, toddler, and child.5-7 Just as fetal breathing movements of amniotic fluid are necessary for lung development, sensory input and fetal movement help shape the central nervous system. Patterns of electrical activity associated with movement and sensory input shape neural networks during synaptogenesis and later determine which pathways are pruned.

While most infants are born near term (ie, 40 weeks’ gestation), with no major difficulties, and grow up without any impairments, the challenge for prediction of outcomes is to recognize those processes that alter or interfere with neuromaturation. The greater challenge is to understand the mechanisms of unfavorable processes and to develop strategies to prevent or promote recovery from them.

RISK FACTORS AND EARLY DEVELOPMENT

We focus on risk factors because it is not possible to make a diagnosis of neurodevelop-mental disability in the neonatal period, even with evidence of brain injury from neuroim-aging studies.1,3,4 The major disabilities (ie, cerebral palsy, intellectual disability) generally can be diagnosed within the first 3 years, but learning disability, attention deficit, and minor neuromotor dysfunction require follow-up to the preschool and school years.3,9,10

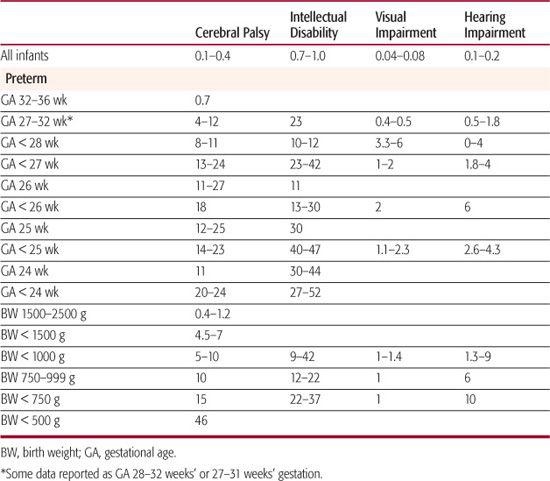

The absence of risk factors does not guarantee a normal outcome. In the general population, 1% develop intellectual disability and 0.1% to 0.4% develop intellectual disability as shown in Table 62-1.3 Up to 30% to 40% of children with cerebral palsy or intellectual disability have no known etiology: Many were born at term and never required neonatal intensive care.3,11 Risk factors for neurodevelop-mental disability vary widely in their predictive value and sometimes provide insight into how prenatal and perinatal complications influence fetal and neonatal development.1-4 Some risk factors are predictive of specific disabilities: low socioeconomic status has a much stronger association with cognitive impairments than with cerebral palsy. Little is known about factors that protect against or promote recovery from early CNS injury.

Fetal maturity at the time of birth plays a significant role in determining neurodevelopmental outcomes.15 Mortality, morbidity, and disability rates increase with decreasing birth weight and gestational age (ie, the proxies we use for maturity). However, just as a 12 year old can be more mature or less mature for age, the same individual variability is seen at each week of gestation. Intrauterine conditions can alter rate of fetal maturation, making the fetus either less (infant of diabetic mothers) or more (intrauterine growth restriction) mature for gestational age.5,12,13

Neonatal illnesses are also strong risk factors for neurodevelopmental disabilities, chronic lung disease, retinopathy of prematurity, and sepsis.3,4 Many medications and technologies used in neonatal intensive care units have not been evaluated for safety, efficacy, and especially their effects on CNS development.

Despite its importance, multicenter randomized controlled trials of neonatal intensive care interventions rarely use neurodevelopment as a primary outcome measure. Instead, many use proxies (eg, intraventricular hemorrhage) that are imperfect predictors of outcome. This is best demonstrated by the delayed recognition of the adverse effects of postnatal steroids on development until follow-up data were reported for several trials.

PRETERM BIRTH

The risk for neurodevelopmental disabilities is highest at the lower limits of viability and improve as gestational age at birth increases.1 Risk factors related to inflammation and infection have been implicated as contributing to preterm birth, complications of prematurity (eg, chronic lung disease), and neurodevelopmental disability.

The prevalence rates of cerebral palsy, intellectual disability, and sensory impairments are all higher in preterm than in full-term infants and tend to increase as gestational age decreases (Table 62-1 and eTable 62.1  ).1,3,9,10,14-16 Although the percentage of children born at 32 to 36 weeks’ gestation who develop cerebral palsy is low (0.7%), it is 6 times higher than that of full-term children (0.1%).11 Higher mortality and morbidity rates and rising birth rates for late preterm infants stimulated the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Fetus and Newborn to publish guidelines for evaluating and managing them at birth.19

).1,3,9,10,14-16 Although the percentage of children born at 32 to 36 weeks’ gestation who develop cerebral palsy is low (0.7%), it is 6 times higher than that of full-term children (0.1%).11 Higher mortality and morbidity rates and rising birth rates for late preterm infants stimulated the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Fetus and Newborn to publish guidelines for evaluating and managing them at birth.19

Table 62-1. Neurodevelopmental Disability Rates (percent) in Preterm and Full-Term Infants

Although the vast majority of preterm survivors do not develop major disability, the high rate of motor and cognitive impairment in infants born at the limit of viability are a major concern (Table 62-1).1,3,18,20,21 Up to a quarter of infants born before 25 weeks, gestation who survive develop cerebral palsy, and up to half have intellectual disability (ie, cognitive scores 2 or more standard deviations below the mean). Greater functional motor impairment (eg, non-ambulatory spastic diplegia or spastic quadriplegia) is seen in infants born before 26 weeks’ gestation. The most immature and sickest infants also have the highest rates of hearing impairment and retinopathy of prematurity.1,16

Preterm birth contributes substantially to the societal burden of cerebral palsy: Of children with cerebral palsy, 40% were born before 37 weeks’ gestation; 16% to 29% were born at 32 to 36 weeks’ gestation, and 32% were born before 32 weeks’ gestation.1 Spastic diplegia is the most common type of cerebral palsy in children born preterm, and it is often mild. Spastic hemiplegia is rarely seen in children born before 26 weeks’ gestation (3%), but its prevalence increases with increasing gestational age.

Neuromotor abnormalities are common (17–47%) in preterm infants during their first year but signal cerebral palsy in only a small proportion of infants (10–20%).1,10,23-26 Minor neuromotor dysfunction may persist with mild abnormalities on examination (asymmetries, tight heel cords), developmental coordination disorder, fine motor dysfunction, difficulties with motor planning, or sensorimotor integration problems. At preschool and school age, these children may have difficulty with adaptive skills (eg, buttoning, tying shoelaces), handwriting, and outdoor athletic activities (eg, playing on the playground or participating in sports). Children with minor neuromotor dysfunction but no major disability are at increased risk for borderline intelligence or other cognitive impairments, specific learning disabilities, behavior problems, executive dysfunction, low self-esteem, and difficulty with peer relationships.1,10,27,28

Populations of children born preterm demonstrate a normal wide range of intelligence quotient (IQ) scores, but when compared to populations of children born at term, they have lower mean cognitive scores and a higher proportion of intellectual disability (eg, formerly called mental retardation, with cognitive scores 2 or more standard deviations below the mean, Table 62-1).1,3,9,15 Preterm children with no neurologic problems or intellectual disability demonstrate higher prevalences of language disorders, visual-perceptual problems, reading disability, difficulty with arithmetic, executive dysfunction, and behavior problems than do children born at term.1,9,15,29-32 Risks for reading and spelling difficulties increase with decreasing gestational age, with significant differences between children born at 33 to 36 weeks and those born at 39 to 40 weeks.32 These more subtle CNS disorders are often unrecognized and can have a devastating impact on the child’s sense of independence, self-esteem, and peer relationships. Early recognition, with appropriate developmental and emotional support, can preserve the child’s self-esteem, improve function, and mitigate secondary social and emotional problems.

The best predictors of major disability in preterm infants are neuroimaging abnormalities, neuromotor abnormalities on examination, and factors related to severity of neonatal illness.1-3,10,17,32,33 Although there are many promising reports that magnetic resonance imaging and diffusion tensor magnetic resonance imaging demonstrate abnormalities that are not seen on ultrasound studies but are predictive of motor impairment, there are still insufficient data for these or other neuroimaging techniques to become standard clinical practice.33-35

Many complications of prematurity, including chronic lung disease, necrotizing enterocolitis, sepsis, and retinopathy of prematurity, are risk factors for worse neurodevelopmental outcome.3,8,35 Chronic lung disease is associated with an increased risk for cerebral palsy, cognitive impairment, language delay, visuo-motor difficulties, memory problems, attention deficits, executive dysfunction, poor academic performance, and behavior problems.36,37 In infants with birth weights below 1000 g, the longer they require ventilation, the lower their chance of survival without severe cognitive impairment or cerebral palsy (24%, 7%, and 0% for 60 days, 90 days, and 120 days respectively).38 Necrotizing enterocolitis requiring surgical intervention increases a pre-term infant’s risk of cerebral palsy, intellectual disability, and visual impairment.39-41 In a study of infants with birth weight under 1000 g, 37% to 38% with sepsis or meningitis had intellectual impairment, and 17% to 19% had cerebral palsy at 18 to 23 months (compared to 22% and 8%, respectively, for infants without documented sepsis or meningitis).42

Many adolescents and young adults with birth weights below 1000 or 1500 g report more functional limitations than those born at term.1,43-46 They have lower academic achievement scores and higher prevalence rates of neurosensory impairment than do full-term controls. They are more likely than controls to have emotional and behavioral problems, including anxiety and depression, withdrawn behavior, and attention problems. Nonetheless, the majority graduated from high school (74–82%), and as many as 30% to 32% pursued postsecondary education. Many find employment, marry, and have children. When compared to controls born at term, they and their parents report less alcohol and drug use, fewer teen pregnancies, and fewer delinquent or other risk-taking behaviors. One 31-year follow-up study reported significantly lower rates of tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drug use in adults born preterm than in adults born at term and no differences in socioeconomic status, psychological functioning, or health-related quality of life.47

IUGR AND SGA INFANTS

Children born small for gestational age (SGA) vary considerably as to long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes, in part due to the etiology and timing of the IUGR as well as a wide range of perinatal complications as discussed in Chapter 47.

Inability to identify an etiology of intrauterine growth restriction leads to a presumptive diagnosis of uteroplacental insufficiency, especially if the infant has relative sparing of head growth, the placenta is abnormal, or the mother had chronic hypertension, preeclampsia, or other vascular disorder. Fetal growth restriction and shunting of blood flow to support brain growth are adaptations to limited intrauterine resources. Although these adaptations improve survival, they increase the neonate’s vulnerability to the stresses of birth and risk for hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease in adulthood. After 30 to 31 weeks’ gestation, progressive intrauterine growth restriction can be accompanied by accelerated fetal pulmonary development and neuromaturation.5,12,13,48 As the intrauterine environment worsens, threatening organ injury and fetal death, this adaptation prepares the fetus for preterm birth and survival. Triggering preterm labor may thus be another adaptation to adverse intrauterine circumstances.

Adaptive mechanisms that help the fetus to survive come at a cost. Using ultrasound to measure Doppler flow velocities in the fetal middle cerebral and umbilical arteries to identify fetuses with evidence of brain sparing, Scherjon and colleagues followed SGA infants and controls.48 At 5 years, children with evidence of fetal brain sparing had significantly lower mean cognitive scores than controls (87 ± 16 vs 96 ± 17). Many studies have demonstrated that full-term SGA children have lower cognitive scores, poorer academic performance, and more attention problems than full-term appropriate-for-gestational-age controls, and fewer young adults born small for gestational age graduated from secondary school than did appropriate-forgestational-age controls.50-53

With good prenatal care and current technology, poor intrauterine growth may be recognized early before fetal growth declines so much that the infant becomes small for gestational age. The obstetrician’s challenge is to time delivery to minimize organ injury from the adverse intrauterine circumstances yet avoid as many complications of prematurity as possible. Preterm SGA infants have the disadvantages of both intrauterine growth restriction and prematurity.53-56 Preterm infants born small for gestational age before 30 to 32 weeks’ gestation have mortality, morbidity, and neurodevelop-mental disability rates similar to those of appropriate-for-gestational-age infants born before 30 to 32 weeks’ gestation, suggesting ineffective mechanisms for adaptation to intrauterine growth restriction this early in pregnancy.

SICK FULL-TERM INFANTS

The many acute neonatal illnesses (eg, sepsis, meningitis, hypoxic-ischemic events, and respiratory failure) and/or major congenital anomalies that require neonatal intensive care increase a full-term newborn’s risk of neurodevelopmental disability. Recent randomized controlled trials of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation or inhaled nitric oxide have generated outcome data for sick and late preterm infants with respiratory failure are discussed in Chapter 61.57-59

Critically ill infants born at or near term who develop respiratory and other organ failure have an increased risk of neurodevelop-mental disability. Intellectual disability occurs in a third of survivors, and significant motor impairment in 5% to 13%. Hearing impairment, which is more common than in extremely preterm infants, can be progressive. These children need frequent hearing tests. Chronic lung disease, growth problems, language delay, attention deficits, learning disability, minor neuromotor dysfunction, and behavior problems are common. Need for cardiopulmonary resuscitation, lower birth weight, sepsis, congenital anomalies, neuroim-aging abnormalities, and neuromotor abnormalities are all additional risk factors. Children with congenital anomalies are more likely to be born preterm, but risks of cerebral palsy and/or intellectual disability are higher even if they are born at term and have no CNS structural anomalies.60-63

REFERENCES

See references on DVD.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree