Otoscopic Examination

Holly W. Davis

Kala Parker

Introduction

Symptoms referable to the ears account for over one third of all pediatric visits to a medical facility (1,2). Patients can present with localized symptoms, such as otalgia and otorrhea, or with nonspecific complaints, such as fever, irritability, and decreased appetite. A small number may be asymptomatic. For this reason, the pediatric physical examination is not complete without an otoscopic examination. Pediatricians, emergency physicians, and family practitioners must therefore be skilled in the techniques of assessment. Otoscopic examination not only is used as a diagnostic procedure for external auditory canal problems and middle ear disease but also can serve as an indirect evaluation of intracranial injury in children with a history of trauma. Otoscopy also provides a means to directly visualize procedures that occur within the ear canal (see Chapters 53, 54, and 56).

Anatomy and Physiology

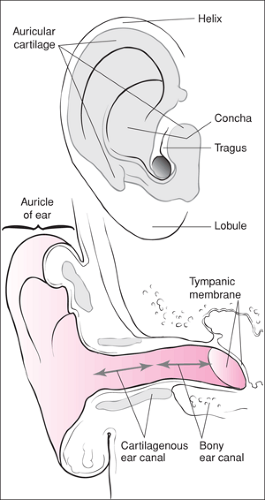

The external ear includes the pinna, auricle, the outer cartilaginous canal, the inner bony canal, and the outer surface of the tympanic membrane (Fig. 52.1). The middle ear includes the inner portion of the tympanic membrane, the three ossicles, and the mastoid air cells (Fig. 52.2). The inner ear is composed of the semicircular canals, the cochlea, and the seventh and eighth cranial nerves. The eustachian tube connects the middle ear with the nasopharynx. When functioning normally, the eustachian tube vents the middle ear, serves as a conduit for drainage of middle ear secretions, and protects the middle ear from nasopharyngeal sound pressure and secretions (1,3). The tympanic membrane is perpendicular to the external auditory canal in children over 1 year of age, while in infancy it is tilted at a more horizontal angle, making visualization of landmarks more difficult (1,2). Additionally, the external auditory canal itself is often slightly angulated in infancy and early childhood. This necessitates applying gentle lateral traction on the auricle to help visualize the tympanic membrane (1,2,4). During the first 4 to 6 months of life, the canal mucosa is somewhat loosely attached to supporting structures and moves readily on insufflation. If care is not taken to inspect the canal as the speculum is inserted, thereby ensuring that the transition between the canal wall and tympanic membrane is visualized, movement of the canal wall during insufflation may be mistaken for a normally mobile drum (1,2).

The wall of the external auditory canal is protected by a waxy layer of cerumen, formed by a combination of viscous secretions from sebaceous glands, watery secretions of apocrine glands, and exfoliated epithelial cells. While the canal is colonized by normal skin flora, the acidic pH of the secretions acts as a chemical barrier against infection (5). Infection of the external canal (otitis externa) can result from a variety of factors. Repeated wetting of the canal wall from swimming, bathing, or high humidity alters the protective coating of wax and renders the surface more susceptible to infection. Conditions causing excessive dryness, underlying skin disorders (e.g., eczema or psoriasis), and trauma to the external canal (from fingernails, cotton swabs, or the presence of a foreign body) predispose this area to infection. Finally, perforation of the tympanic membrane in a patient with acute otitis media, by releasing purulent material into the external auditory canal (1,3,5), can also cause external canal infection.

The major predisposing factor for development of acute middle ear infection (otitis media) is eustachian tube dysfunction. The high incidence of otitis media in young children who are otherwise healthy partly reflects the immaturity of the eustachian tube of the young child. It is shorter, less rigid, and more horizontally oriented in younger children, thus allowing organisms from the nasopharynx to reach the middle ear

region more easily (1,2,3,6). These features of the eustachian tube also can result in impairment of pressure regulation and clearance of fluid from the middle ear. Furthermore, infants and young children are prone to functional obstruction of the eustachian tube. Lack of stiffness in the cartilaginous supporting structures predisposes to collapse of the tube, which impairs venting of the middle ear (4). As oxygen is absorbed by mucosal cells, negative pressure develops within the middle ear. When venting of air eventually does occur, the vacuum created facilitates aspiration of nasopharyngeal secretions into the middle ear (4).

region more easily (1,2,3,6). These features of the eustachian tube also can result in impairment of pressure regulation and clearance of fluid from the middle ear. Furthermore, infants and young children are prone to functional obstruction of the eustachian tube. Lack of stiffness in the cartilaginous supporting structures predisposes to collapse of the tube, which impairs venting of the middle ear (4). As oxygen is absorbed by mucosal cells, negative pressure develops within the middle ear. When venting of air eventually does occur, the vacuum created facilitates aspiration of nasopharyngeal secretions into the middle ear (4).

The anatomic and physiologic abnormalities associated with cleft palate and other craniofacial anomalies produce similar functional impairment and obstruction (1,2,3,6). Tonsillar enlargement can also cause mechanical obstruction of the eustachian tube, predisposing to infection. The tonsils and adenoids normally enlarge over the first 8 to 10 years of life and then gradually decrease in size. Less commonly, nasopharyngeal tumors may be the source of mechanical obstruction (1,2,3,6). In addition, organisms can enter the middle ear space from the external canal through a tympanic membrane perforation or via hematogenous spread (1,6).

Acute otitis media consists of inflammation of the mucoperiosteal lining of the middle ear. Respiratory viruses set the stage for a substantial proportion of cases of bacterial otitis by inducing respiratory epithelial injury and by causing congestion of the respiratory mucosa of the nose, nasopharynx, and eustachian tube. The resulting eustachian tube inflammation and edema impair middle ear drainage and make it easier for pathogenic bacteria that have colonized the nasopharynx to gain access to the middle ear. With infection, the mucosal lining becomes inflamed and weeps, resulting in accumulation of mucopurulent material in the middle ear space (1,2,6). As pressure in the middle ear increases, the membrane tends to bulge. Rupture may occur if pressure becomes great enough to cause ischemic necrosis. When the middle ear is filled with fluid, tympanic membrane mobility is markedly reduced on both positive and negative pressure. If, however, some venting of the eustachian tube occurs, air and fluid may be present with a milder decrease in mobility, and an air fluid level or bubbles can be seen (2,6).

Otitis media with effusion refers to the presence of clear, uninfected fluid within the middle ear. The membrane is neither opacified nor inflamed and does not tend to bulge out. Typically, it is seen in children with eustachian tube dysfunction, often following resolution of an acute infection. On pneumatic otoscopy, there is decreased tympanic membrane mobility with both positive and negative pressure (1,2,6). If negative pressure has developed within the middle ear, the drum may move primarily when negative pressure is applied (2). This condition may persist for weeks to months. Some affected children experience a decrease in hearing, but most patients are asymptomatic (1,2,6).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree