Historically, there has been a distinction between juvenile-onset OCD and adult-onset OCD. Many surgeons have suggested that skeletally immature patients (juvenile onset) have a better prognosis that has been inconsistently defined in the literature as either radiographic healing or merely resolution of pain.4,5,9,11,12,15 Despite the lack of an open physis at the time of diagnosis in an adult OCD, however, many authors suggest that the only true difference between juvenile- and adult-onset OCD is purely a reflection of patient age at the time of diagnosis.

A recent definition of human OCD lesions, proposed by the Research in Osteochondritis of the Knee (ROCK) study group, highlights the fact that these are (1) focal, (2) idiopathic, (3) involve subchondral bone, and (4) risk instability and disruption of articular cartilage with potential long-term consequences, such as premature osteoarthritis.16 This definition is the summary of epidemiology, etiology, classification, and assessment of OCD.

There are only three true epidemiology papers regarding knee OCD.10,17,18 The first was performed by Marsden and Wiernik18 in a review of 18,405 radiographs at a military hospital. They found an incidence of symptomatic OCD of 2.3% of the radiographs and an overall incidence (including incidental discovery) of 4% OCD in their cohort.

A classic study by Linden10 in 1977 from Malmo, Sweden demonstrated an incidence of 29 per 100,000 boys and 19 per 100,000 girls. More importantly, after he reviewed radiographs and obtained follow-up with many of these patients 33 years later, he discovered that there was an “accumulated risk of roentgenographic gonarthrosis in patients who have had osteochondritis dissecans.” If he assumed the risk of arthritis to be 0% at the start of life, this was unchanged at age 40 years with an OCD; but the risk increased to 70% at age 48 years and continued to increase to 95% at 70 years of age. However, in those initially discovered with juvenile-onset OCD, he could not directly correlate any pathology such as gonarthritis with their OCD directly.

The only other study was published in 2014 and included a review of just over 1 million children aged 2 to 19 years within a closed health system.17 These authors found 192 children with 206 OCD lesions of the knee. The majority (64%) of the lesions involved the medial femoral condyle, and the overall incidence seen in the cohort was 18.1 per 100,000 boys and 3.9 per 100,000 girls. The incidence of knee OCD varied by ethnicity: non-Hispanic white was 10.3 per 100,000 overall (17.3 and 3.0 per 100,000 for boys and girls, respectively), non-Hispanic black was 10.3 per 100,000 overall (17.3 and 3.0 per 100,000 for boys and girls, respectively), Hispanic was 8.6 per 100,000 overall (14.3 and 2.8 per 100,000 for boys and girls, respectively), and Asian was 4.7 per 100,000 overall (9.1 and 0.0 per 100,000 for boys and girls, respectively). These authors performed multivariable logistic regression analysis that revealed a 3.3-fold increased risk of OCD of the knee in children aged 12 to 19 years compared with those aged 6 to 11 years. Moreover, boys had 3.8 times greater risk of OCD than girls.

Finally, there is the discrete possibility that knee OCD may occur in both knees. In the literature, there is a relatively wide range of bilaterality noted with about a 3% to 30% chance of discovering it in both knees by x-ray.5,18–23

No definitive etiology has yet been determined for the origin of knee OCD. There are, of course, many hypotheses that have been presented and tested primarily via ex vivo histology. The potential etiologies include inflammation, spontaneous osteonecrosis and vascular deficiency, genetic predisposition, and repetitive trauma. Each of these will be discussed.

As suggested by the name “osteochondritis,” the first description in 1888 by König,2 by definition was atraumatic and it was postulated to be a result of inflammation. However, histologic studies have not supported this etiology7,24; instead, these works appear to highlight findings of necrosis within the OCD lesions rather than inflammation.

Based on their histology findings, Green and Banks12,19 proposed that ischemia was the primary etiology, and Milgram,22 identifying revascularization in partially detached OCD lesion, further promoted this concept of poor vascularity. Yet, Yonetani and colleagues25 found no evidence of necrosis on biopsies. Uozumi and colleagues26 discovered a discrete absence of subchondral bone in many of their biopsy samples and, in those who had an osseous component present, only two demonstrated no viable osteocytes. The difference between the first two studies and the second two is state of the OCD lesion prior to biopsy. When the lesion was unstable (or even a loose body) at the time of biopsy, then necrosis was found by microscopic evaluation. However, if the lesion was fully intact and in situ, then there was less definitive evidence for avascular necrosis.

Another hypothesis of the etiology is familial inheritance of OCD lesions. A mild form of skeletal dysplasia with associated short stature has even been proposed.9,23,27–29 Two different authors, via different family tree assessments, have identified what they believe to be an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern.9,28 In contrast, Petrie30 reported on a radiographic examination of first-degree relatives of those patients with known OCD and discovered only 1.2% with OCD themselves. This suggests that the majority of knee OCD does not follow a predictable inheritance pattern. However, it does not exclude the possibility that genetics may still play a role in OCD etiology.

Whether the aforementioned etiologies are primary or secondary remains a question unto itself, and the concept of repetitive microtrauma is another distinct possibility. For example, despite the original description by König, there could be a significant traumatic event leading to avascular necrosis or there could be repetitive traumatic events that progressively develop vascular disruption. In 1933, Fairbanks31 proposed traumatic contact between the lateral aspect of the medial femoral condyle and the tibial spine; yet, this theory would only explain OCD lesions on the lateral aspect of the medial femoral condyle. However, the idea of repetitive trauma still holds our attention for the other locations of OCD as well. Aichroth6 demonstrated that 60% of the patients with knee OCD in his cohort were involved in high-level, competitive sports. Moreover, Linden11 showed an association between the incidence of OCD and the increased involvement in organized sports in Sweden between 1965 and 1974. A large multicenter study conducted by the European Pediatric Orthopaedic Society demonstrated that nearly 55% of those with OCD were regularly active in sports or performed “strenuous athletic activity.”20 Evidence to support repetitive trauma as an etiology for OCD is mostly conjecture and circumstantial at best.

Perhaps abnormal pressure on the cartilage anlage is a better way of describing “microtrauma,” as several studies have noted associations between lateral femoral condyle OCD lesions and discoid menisci.32–34 Moreover, there is an apparent association with poor mechanical axis alignment and the presence of knee OCD.35 In fact, the association between alignment shifts and location of OCD development was predictive, with varus malalignment predicting medial OCD lesions and valgus malalignment predicting lateral OCD lesions.35 These findings suggest that aberrant mechanical pressure on the condyles may be an etiology to the formation of OCD (at least in the knee).

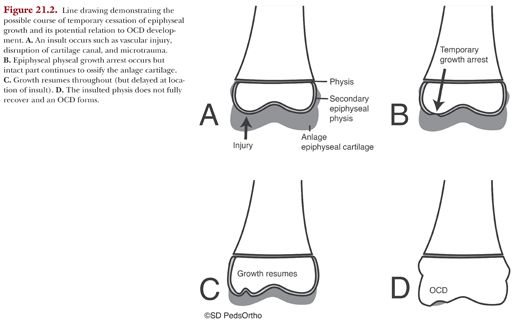

Perhaps the unifying theory can be found in the work by our veterinary colleagues on horse and pig comparative models. They believe that the OCD lesions in these animals originate within the cartilage anlage of the subchondral bone.13,14 They have actually been able to create an animal model for OCD by description of the cartilage canals (which is the blood supply to the epiphyseal anlage cartilage). This further hints toward a possible traumatic injury that disrupts the blood supply. They also suggest modifying the term osteochondritis to osteochondrosis given the complete lack of inflammation being seen as a possible etiology. Furthermore, they would include the modifier “dissecans” when the articular cartilage becomes involved but recommend using the terms latens when there is only necrosis of the anlage cartilage or manifesta in the presence of focal failure of enchondral ossification to differentiate the timing of discovery. In other words, these authors believe that by the time this pathologic process becomes clinically evident in the knee, it has already evolved through all three stages and is in the final necrotic form of OCD (Fig. 21.2).

This concept is not new to human physicians, but the concept of disrupted cartilage canals is novel to the previous hypothesis of Ribbing36 in 1937. His thesis was presented in a 107-page supplement to the journal Acta Radiologica discussing abnormalities of endochondral ossification of the epiphysis. His hypothesis was then further modified by Barrie7,24 to further define possible etiologies of OCD formation via epiphyseal secondary growth. Basically, at an index event, there is an insult (single or repetitive) to the endochondral epiphyseal growth plate or perhaps to the cartilage canals just deep to subchondral bone. With skeletal development, the uninjured region of endochondral epiphyseal ossification continues to ossify unhindered, creating an ever enlarging OCD central to the normal growth.

Although the concepts of disrupted cartilage canals or endochondral epiphyseal growth plates are appealing etiologies, there remains a gap in the explanation regarding how and why these structures become injured in the first place. All children are quite active, jumping, playing, running, and falling. So why do some develop an OCD and some do not develop an OCD? This question is yet to be answered.

The simplest form of knee OCD classification is that set forth by Hefti and colleagues20 that merely describes location of the OCD. The most common site of OCD is the lateral aspect of the medial femoral condyle (51% involvement), with other sites being involved with less frequency: 19% central medial femoral condyle, 17% lateral femoral condyle, 7% medial side of the medial femoral condyle, and 7% patella. It may be important to note that irregular ossification centers of the distal femoral condyle tend to be found more posteriorly on the condyle (although they can be anywhere on the condyle) and are associated with younger age. Cahill12 wrote a review of OCD and identified multiple other authors who have similarly classified knee OCD by location, but he makes no mention of classifying the lesions in any other method (stability, outcomes, etc.).

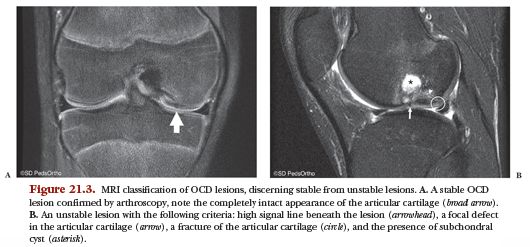

De Smet and colleagues37 took things to the next level and classified the OCD either stable or unstable and correlated their magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings with arthroscopic findings. They reported that a high signal interface between the OCD lesion and the normal femoral bone was indicative of instability by arthroscopy. This same author then later improved his assessment by MRI and added three other signs of instability that are discussed in the following text (Fig. 21.3).38