Orofacial Anesthesia Techniques

Zach Kassutto

Introduction

Orofacial nerve blocks and infiltrations can be used for regional anesthesia in the event of orofacial pathologies such as dental caries, tooth and alveolar fractures, and soft-tissue trauma to the lower half of the face. These procedures are most commonly performed by dentists and oral surgeons in the outpatient setting. Patients requiring these types of procedures also are seen regularly in the emergency department (ED). Given the numerous approaches and types of procedures available, this chapter will review only those procedures that have the greatest utility and success rate and the lowest rate of complications.

When used for the relief of pre-existing pain, these procedures are temporizing only. Using a longer-acting anesthetic agent can extend their effect. These procedures can be performed successfully in children of any age. In younger and uncooperative children, the procedures are more difficult to carry out. Adjuncts to the procedure include emotional preparation and support (Chapter 2), procedural sedation (Chapter 33), appropriate restraint (Chapter 3), and mucosal topical anesthetics. Honesty and sincerity also must be used, as they are perhaps the most important preparation for any procedure with pediatric patients.

Anatomy and Physiology

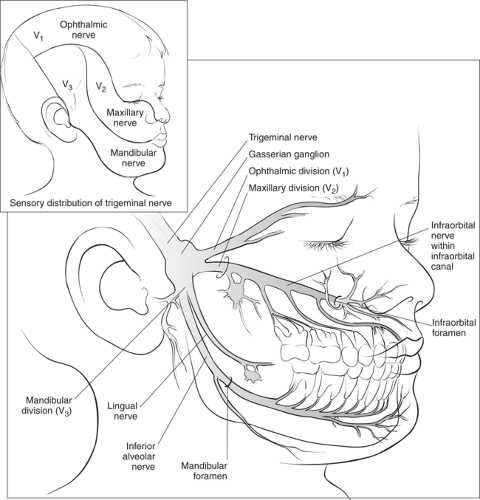

Orofacial anesthesia blocks transmission of painful stimuli via one or several afferent branches of the fifth cranial (trigeminal) nerve. Three primary divisions of the fifth cranial nerve on each side of the face are designated V1, V2, and V3 (Fig. 62.1).

V1, the ophthalmic division, innervates structures above the mouth. V2, or the maxillary division, supplies sensory fibers to the various structures in and around the maxilla. These include all the maxillary teeth and their associated gingivae; the entire palate and tissues posterior to this, including the tonsillar region; the lower eyelid; the side of the nose; the upper lip; and the mucous membranes of most of the nasal cavity. The palatine branches (greater, lesser, and nasopalatine nerves) branch off before the nerve enters the infraorbital canal. These nerves innervate the soft-tissue structures of the posterior mouth and the throat.

The posterior superior, middle superior, and anterior superior alveolar nerves are the next branches of V2. The posterior superior alveolar nerve branches off before entering the infraorbital canal and innervates the maxillary sinus and the maxillary molars and their gingivae. The middle superior and anterior superior alveolar nerves separate from the maxillary nerve trunk as it traverses the infraorbital canal (where it is called the “infraorbital nerve”). Together, these nerves supply the anterior maxillary teeth and their associated structures as far posterior as the maxillary premolars or primary molars. The infraorbital nerve exits the skull via the infraorbital foramen and its terminal branches innervate the lower eyelid, the alae of the nose, and the upper lip. Anesthetic applied at the infraorbital foramen allows repair of ala or upper lip injuries without the swelling associated with direct infiltration.

The mandibular division, or V3, supplies motor innervation to the muscles of mastication and sensory fibers to the mandible. The inferior alveolar nerve is the largest branch of the mandibular nerve. It enters the mandible via the mandibular foramen, which is located on the internal surface of the ramus. It then traverses the mandible through the mandibular canal, where the nerve and its branches innervate all the teeth of the mandible on each respective side. The lingual nerve is an early branch of the mandibular division. This branch travels with the inferior alveolar nerve until it enters the mandibular canal. Then the lingual nerve enters the base of the tongue. There it supplies sensory fibers to the anterior two thirds of the tongue, the floor of the mouth, and the lingual aspect of the mandibular gingivae. Anesthetic applied near the mandibular foramen will usually anesthetize both the lingual and inferior alveolar nerves.

Indications

Orofacial anesthesia can be used for pain relief (e.g., dental abscess, caries) or for the prevention of pain (e.g., tooth extraction, facial and/or oral laceration repair, facial and/or dental abscess drainage). Procedures are classified as nerve blocks or direct infiltration.

Nerve blocks allow the use of small amounts of anesthetic applied to a small area for anesthesia of larger areas. In this way, manipulation of infected tissues can be avoided and anatomical landmarks are not distorted. An example is using an infraorbital nerve block for repair of the vermilion border in upper lip lacerations. Nerve blocks also decrease the risks of using larger amounts of anesthetic and avoid the need for injection of anesthetic in areas that are more susceptible to pain. Infiltration anesthesia is used when smaller areas of anesthesia are needed. Examples include tooth pain from caries or isolated tooth injury from trauma. Nerve blocks and infiltration anesthesia for other parts of the body are described in Chapters 35 and 55.

The need for consultation depends on the patient’s exact injury and the practice at a given institution. Possible consultants include dentists, oral surgeons, otorhinolaryngologists, and plastic surgeons. Consultation should be considered for cases involving mandibular fractures, nerve injury from trauma, difficulty achieving anesthesia, or any contraindications to the procedure.

Absolute contraindications to the procedures in this chapter include known allergy to the anesthetic agent and grossly distorted anatomical landmarks. Injecting through infected tissue (e.g., tooth abscess) is a relative contraindication (2). Local anesthetics are less effective when applied in regions of inflammation (3). Manipulating a needle through infected tissues also increases the risk of spreading the infection to other adjacent areas or into the blood stream. Whenever possible, a nerve block (as opposed to direct infiltration) should be used in this type of situation.

Equipment

See also Table 62.1.

1″ × 1″ sterile gauze pads

Cotton-tipped applicators

TABLE 62.1 Equipment for Orafacial Anesthesia

1″ × 1″ sterile gauze pads

Cotton-tipped applicators

Suction

Supplies for universal precautions (latex gloves, protective eyewear, surgical mask, and moisture-repellent gown)

Anesthetic agents

Sterile syringe and needle

Resuscitation equipment

Yankauer suction (a large-bore suction device such as a Yankauer device is preferred for removing any secretions, blood, or emesis; see Chapter 13)

Syringe

27-gauge, 1- or 1.25-inch straight needle or aspirating dental syringe

Orofacial anesthesia can be performed using medical syringes and needles commonly available in the ED but is more easily accomplished using dental equipment specifically designed for this task, such as an aspirating dental syringe that uses cartridges (carpules) of anesthetic solution and disposable needles (4). This type of syringe affords the physician a better grasp of the instrument and the ability to aspirate with the same hand that is holding the syringe. This frees the other hand to hold, stabilize, and retract the involved tissues.

Various suggestions have been made as to the best size needle to use for the procedure. Large bore needles make the procedure unduly painful and could compromise exact placement of the needle tip. Narrower needles make aspiration more difficult and increase the risk of needle breakage. Some authorities believe that a needle smaller than 25 gauge may increase the risk of inadvertent intravascular injection (i.e., no blood on aspiration despite the needle being inside a vessel). Others believe that this risk is small and that slow injection after aspirating further minimizes this risk. Most sources recommend a 27-gauge “short needle” (1 inch) for most infiltrations and blocks and a 27-gauge “long needle” (1.25 inch) for older adolescents.

Orofacial anesthesia techniques in children differ from adults because of the smaller size of the skull and the characteristics of the bone. In general, the depth of needle insertion needs to be adjusted for the size of the child’s anatomy. Relevant variations in size will be discussed under each procedure.

Topical anesthetic

20% benzocaine

5% to 10% lidocaine

Commercial topical dental anesthetics are available in liquids, gels, ointments, and sprays. The most commonly used preparations contain benzocaine (e.g., Hurricane, a flavored preparation of 20% benzocaine). If a specific dental preparation is unavailable, 5% to 10% lidocaine or 20% benzocaine can be used. Less concentrated anesthetics usually prove to be ineffective (4).

The oral mucosa is supplied by a rich vascular network. Anesthetics applied topically may be absorbed into the systemic circulation. The dose of topical anesthetic, although often difficult to quantify, must be considered when calculating the overall dose of anesthetic that a patient receives. Benzocaine is the preferred agent because it has little systemic absorption when applied topically (5) (although methemoglobin has been reported rarely after its topical use). Anesthetic sprays are discouraged because they tend to cover larger areas than required for the procedure.

Injectable anesthetic

2% lidocaine with epinephrine 1:100,000

3% mepivacaine

0.5% Bupivacaine

Many dental anesthetics are commercially available for injection in dental anesthetic carpules. These carpules each contain 1.8 mL of anesthetic and insert into standard dental aspirating syringes. They cannot be directly adapted for use with other injecting devices commonly available in EDs. The contents, however, can be drawn into a standard disposable syringe through the carpule’s rubber stopper. Care must be taken to use sterile technique when doing this. The standard solution used by dentists is 2% lidocaine with epinephrine 1:100,000. In cases where a prolonged effect is desired, longer-acting agents such as bupivacaine also are available. Long-acting agents are usually avoided for intraoral anesthesia when the oral mucosa or tongue may be involved (e.g., inferior alveolar block). This is especially important in preadolescent or developmentally delayed children who may self-inflict injury by biting their numbed oral tissues. Less commonly used agents include Novocain, prilocaine, and etidocaine.

Anesthetics are available with or without vasoconstrictors. Most practitioners prefer using a vasoconstrictor (such as epinephrine 1:100,000 or 1:50,000), as it slows anesthetic absorption into the surrounding tissues. This allows injection of smaller doses of anesthetic, prolongs the anesthetic effect, and provides for hemostasis. For patients in whom vasoconstrictors are contraindicated (as with certain cardiac anomalies or conduction abnormalities), 3% mepivacaine without epinephrine is the agent of choice. Some dentists advocate warming anesthetic solutions to body temperature before injection to make the injection less painful and anesthesia onset more rapid.

Universal precaution supplies

Latex-free examination gloves

Protective eye wear

Surgical mask

Moisture-repellent gown

Standard cardiopulmonary resuscitation equipment should be readily available in the unlikely event of an adverse reaction to the medications or procedure.

Procedure

Topical anesthesia of mucous membranes can reduce the pain associated with orofacial anesthesia and should be considered before any intraoral injection. In the apprehensive patient, the physician must weigh the extra time involved in undertaking this procedure versus the transient pain of passing a thin needle through the oral mucosa. Most topical anesthetics are pleasant tasting, but if unpleasant, can increase the patient’s apprehension (5).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree