Operative Management of Pelvic Organ Prolapse

Kris Strohbehn

Holly E. Richter

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is a common condition affecting women. While many women live with varying degrees of POP without treatment, it is estimated that over 200,000 surgical procedures are performed in the United States annually to treat this condition. More than 1 in 10 women will have surgical treatment of prolapse and/or urinary incontinence by the time they reach 80 years of age. The repairs are not always successful, and 1 in 3 women who undergo surgery for urinary incontinence or prolapse need to undergo a subsequent procedure. The risk factors, anatomic changes, and demographics of POP are covered in Chapter 48.

Despite the fact that up to 50% of women over the age of 50 have physical findings consistent with some degree of POP, fewer than 20% seek treatment for this condition. This may be due to a number of reasons including lack of symptoms, embarrassment, or misperceptions about available treatment options for this condition. Recent estimates predict an increased demand for prolapse surgery by 45% in the next 30 years. To effectively use financial resources in the surgical management of POP, it is imperative to perform surgeries that are evidence based to improve outcomes and minimize recurrences. The authors believe that nonsurgical options, including observation or a trial of a pessary, are of low risk to patients and should be considered first, if acceptable to the patient.

This chapter will review different surgical options for treating POP, including transvaginal repairs, open abdominal repairs, laparoscopic repairs, and new percutaneous needle or trocar repair kits as well as a combination of these procedures. Each of these surgical approaches to treat POP may use native ligaments and tissues for repair. Alternatively, some surgeons utilize biologic grafts for selected repairs, including xenografts, allografts, and autologous grafts. Finally, synthetic graft materials are frequently utilized via transvaginal, laparoscopic, and open abdominal repairs. A brief discussion of these options and the pros and cons of each will be included in this chapter.

Preoperative Considerations

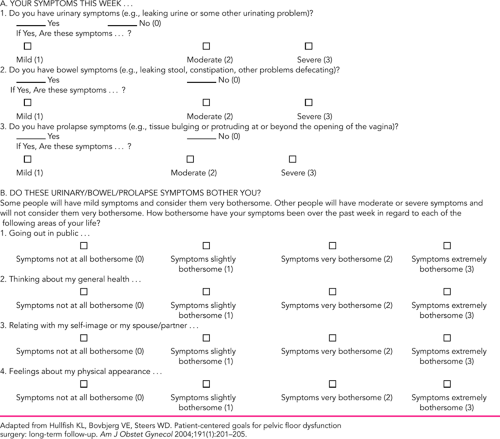

A careful preoperative evaluation of patients with POP is crucial in determining whether surgical repair is the right treatment choice for an individual and if so, which procedure is most appropriate. The decision to operate for POP should be based on the degree of POP symptom bother that a patient is experiencing. Consideration of the patient’s postrepair goals and their risks should be addressed prior to surgery. Symptom-based scoring questionnaires have been introduced and validated to assess the impact of POP on quality of life. There are a wide complex of symptoms associated with POP, including urinary incontinence, voiding dysfunction, anal incontinence, defecatory dysfunction, sexual dysfunction, and prolapse symptoms, that are also commonly reported in women without POP. However, it is more common for subjects to have symptoms when the prolapse extends to or beyond the hymen.

Determination of a patient’s bother prior to considering surgical approach is useful to assess whether or not surgery

offers hope of alleviating her symptoms. In determining bother, it can be helpful to ask the patient if her prolapse is preventing her from doing things that she would like to do. For example, if an individual has stopped exercising because of POP, this may have great impact on her overall health. In the authors’ practice, a simple but nonvalidated scoring system is used to assess bother for specific symptoms (Table 49.1). A more in-depth validated assessment of impact on quality of life has been introduced by Barber and colleagues and is validated for subscales of colorectal function, urinary incontinence, and prolapse. Whether or not a validated scoring system is used, making the effort to determine bother is useful in determining preoperative goals and postoperative outcomes.

offers hope of alleviating her symptoms. In determining bother, it can be helpful to ask the patient if her prolapse is preventing her from doing things that she would like to do. For example, if an individual has stopped exercising because of POP, this may have great impact on her overall health. In the authors’ practice, a simple but nonvalidated scoring system is used to assess bother for specific symptoms (Table 49.1). A more in-depth validated assessment of impact on quality of life has been introduced by Barber and colleagues and is validated for subscales of colorectal function, urinary incontinence, and prolapse. Whether or not a validated scoring system is used, making the effort to determine bother is useful in determining preoperative goals and postoperative outcomes.

Setting realistic expectations and goals with the patient prior to prolapse repair is important. As part of the discussion prior to surgery, a review of possible outcomes (good and bad) should be reviewed with honesty and, if possible, with the surgeon’s individual outcome data. The discussion should include potential negative impact on sexual function and visceral functions, such as bladder and bowel continence and evacuation after anatomic correction of prolapse. If a patient is bothered by prolapse but is without symptoms of urinary incontinence, she will be

understandably upset with her outcome if she develops de novo urinary incontinence. By the same token, someone who has mild urinary incontinence preoperatively who develops de novo urinary retention postoperatively may have elected to live with her mild incontinence compared with the voiding dysfunction she now suffers with.

understandably upset with her outcome if she develops de novo urinary incontinence. By the same token, someone who has mild urinary incontinence preoperatively who develops de novo urinary retention postoperatively may have elected to live with her mild incontinence compared with the voiding dysfunction she now suffers with.

A review of an individual’s prior abdominal and pelvic surgeries is imperative to planning a prolapse procedure. If a patient has had several laparotomies, is morbidly obese, or there is a suspicion for severe abdominopelvic adhesions, the surgeon should consider a vaginal repair. At a minimum, preparation for possible change in the planned repair may be in order, especially if inadvertent enterotomy occurs intraoperatively. If a patient has failed prior prolapse surgeries with native tissue repairs, then consideration of a mesh-augmented or other graft repair should be entertained.

Other considerations regarding the approach to repair include surgeon experience, patient age, other comorbidities, and pelvic muscle strength. Assessment of individual surgeon outcomes may help to determine which prolapse repairs are best suited for an individual’s practice. A focus on outcomes in practices for procedures is being mandated with adoption of the National Surgery Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP).

As part of the focus on excellent outcomes, prophylactic antibiotics should be considered prior to any POP procedure, especially in cases where the vaginal epithelium is disrupted. Within 60 minutes of the incision start, 1 g of cefazolin or a similar broad-coverage antibiotic is administered intravenously. The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) practice bulletin guidelines are helpful for decisions regarding prophylaxis. Prophylaxis for deep venous thrombosis should be considered for any pelvic surgery that is anticipated to take longer than 30 minutes, and the authors employ intermittent pneumatic compression stockings in such cases.

The age of the patient may help to direct which surgical approach is suitable. Many experienced surgeons advocate vaginal repairs for older patients, but using age cutoffs alone may be inappropriate. It is common knowledge that there are 80-year-old women who are more active and in better health than some 50-year-old women. As a generalization, it makes sense to consider a quicker, less invasive repair such as a transvaginal repair or colpectomy with colpocleisis for a frail, inactive patient. This makes sense to reduce morbidity, as inactive individuals are less likely to place stress on the repair. However, the lower morbidity may be at the cost of lower success due to potential diminished strength of the native tissues that may be inherent in frail or elderly patients.

The selection of repair may also depend on whether the levator ani muscles will appropriately protect the ligaments. If a patient is unable to contract her levator muscles, there is likely to be more load on her native ligaments, with possible added risks of failure over time. If it is apparent that there is no protection of the connective tissue support from the pelvic musculature, the choice of a synthetic graft to compensate for lack of muscular support seems sensible.

Planning a prolapse repair requires consideration of the impact of the function of the pelvic organs in addition to anatomic support. Urodynamic evaluation has been recommended by some, even if urinary incontinence is not a symptom of the patient. Urodynamic evaluation may assist in identifying occult urinary incontinence in women with prolapse who leak with a full bladder when the prolapse is reduced. Pessary or barrier testing has also been used to try to assess risks for occult stress urinary incontinence. In the recently published CARE trial, a prophylactic Burch procedure was effective at reducing the risk of stress urinary incontinence among women without preoperative symptoms of such incontinence who underwent mesh sacral colpopexy for the treatment of prolapse. The reduction in risk of stress urinary incontinence did not result in a higher rate of voiding dysfunction or bladder storage symptoms. There are no data available regarding midurethral sling procedures as a prophylactic procedure.

Operative Repairs

The aims of surgical management of POP are to:

Reduce the prolapse

Improve symptoms of POP, the lower urinary tract, and bowel

Restore or improve sexual functioning (except after colpocleisis), and correct coexisting pelvic pathology.

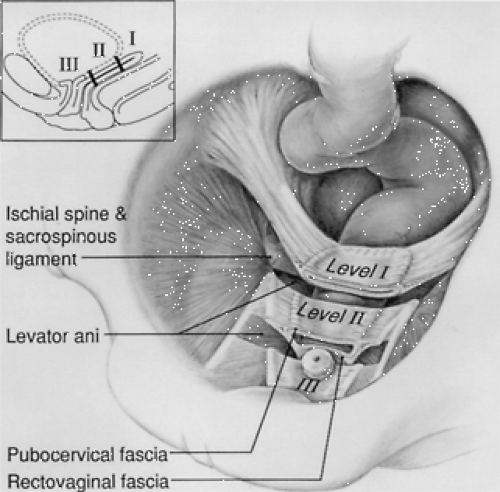

As mentioned previously, the surgical approach for POP includes vaginal, abdominal, and laparoscopic routes. Anatomic studies have demonstrated different levels of support, and POP may result from a single or combination of support defects (Fig. 49.1). Surgical management may therefore involve a combination of repairs including the anterior vaginal wall, vaginal apex, and posterior vaginal wall.

The surgical route is typically chosen based on the type and severity of prolapse, combined with the surgeon’s training and expertise as well as patient functional level and preference, rather than on primary consideration of surgical outcome. Surgical procedures for POP can be categorized into three groups: restorative procedures that use the patient’s endogenous support structures to restore normal anatomy; compensatory procedures that augment defective support structures with autologous, allogenic, or synthetic graft material; and obliterative procedures that stricture the vagina. These categories are somewhat arbitrary and not entirely exclusive. For example, graft material may be used to replace support that is deficient or to reinforce repairs. Graft use in abdominal sacral colpopexy (ASC) substitutes for the cardinal and uterosacral ligaments that would normally support the vaginal apex. When vaginal function is

desired by the patient, restorative or compensatory procedures are utilized, whereas an obliterative procedure may be utilized when there is no desire to retain sexual function of the vagina.

desired by the patient, restorative or compensatory procedures are utilized, whereas an obliterative procedure may be utilized when there is no desire to retain sexual function of the vagina.

Whether to repair all defects seen is controversial, especially if the patient is asymptomatic. Restorative repairs may be less successful than compensatory repairs in patients with generally “poor tissue,” and at times, one defect repair may exert more tension on the repair of another defect. Each case should be individualized based on the patient’s presentation, expectations, the specific anatomical defects noted (preoperatively and, at times, intraoperatively), and on the presence or absence of lower urinary and bowel dysfunction symptoms.

The following sections will describe surgical approaches of prolapse in the anterior, apical, and posterior vaginal components. Vaginal, abdominal, and laparoscopic approaches will be reviewed for each compartment.

Vaginal Approaches

Anterior Compartment

Surgical management of the anterior compartment continues to be a challenge for all pelvic surgeons. In most published series, the anterior wall is the most common site of objective failure with different surgical approaches to POP.

Anterior Colporrhaphy

Anatomic correction of an anterior defect or cystocele will generally relieve symptoms of protrusion and pressure and will usually improve micturition function when abnormal micturition is associated temporally with the defect and if there is no associated neuropathy. If a single, well-defined midline defect is recognized, excision of the weak vaginal wall and an imbricating closure of the defect may be performed. However, recent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and anatomic measurement studies indicate that at least one third of the descent of cystoceles is due to loss of apical support, so it is important to determine whether the apex needs to be suspended as well. Most central anterior defects require a more extensive dissection of the vesicovaginal space. In the case where the cuff is well suspended, the authors typically grasp the vaginal epithelium vertically with two Allis clamps cephalad to the urethrovesical junction and incise with the knife. With the use of a Metzenbaum or comparable scissors, the vaginal epithelial and subepithelial layers are separated from the fibromuscular layer out to a point lateral to the defect up to the cuff or cervix; this is followed by midline plication of this tissue with either a running or interrupted delayed absorbable suture such as polyglactin (Vicryl, Ethicon, Somerville, NJ) or no.1 polydioxanone (PDS, Ethicon, Somerville, NJ), excision of excess epithelium, and closure. The repair is similar at the time of concomitant vaginal hysterectomy or apical cuff suspension except that the dissection proceeds in a cephalad to caudad fashion. It appears of great importance to ensure that the continuum of repaired fibromuscular tissue to a well-supported vaginal apex be maintained.

Recurrence rates of traditional fibromuscular connective tissue plication anterior repairs vary in the literature from 5% to 90%; however, studies define recurrence in numerous ways from minimal prolapse to stage III descent. The clinical significance of recurrent asymptomatic cystoceles (stage I and some stage II) is debatable because many of these do not progress to larger defects. The authors’ interpretation of the literature is that when traditional anterior repairs are performed with patients with a pelvic organ prolapse quantitation (POP-Q) system of measurement of stage II or greater cystoceles (frequently concurrently with other procedures), a recurrence rate of stage II or greater prolapse of up to 20% to 40% is not uncommon. Many studies do not define how the subjects were evaluated postoperatively and vary in respect to patient populations, type and severity of defects, presence of concurrent defects, surgical technique, and follow-up time and length. Some studies have suggested higher recurrence rates when these repairs are performed concurrently with sacrospinous suspensions and hypothesize that this type of apical suspension may predispose the repair anterior wall to greater pressure transmission. Other possibilities of the higher failure rates in these studies are the fact that the patients having concurrent repairs may be more likely to have more complicated forms of prolapse or, possibly, more defective “pelvic floors” than other groups of patients.

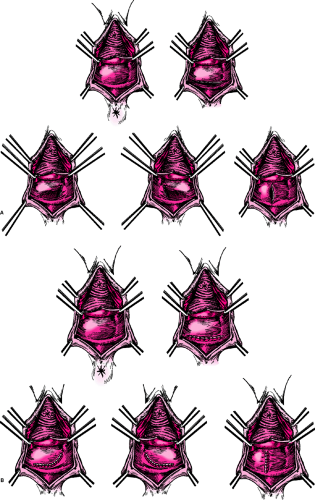

The addition of adjunctive graft materials has been employed in the past decade to try to improve success rates. Two randomized trials suggest modest improvement in success after 1 year when polyglactin mesh (Vicryl, Ethicon, Somerville, NJ) was placed over the midline plication compared with standard repair. However, most

surgeons have abandoned this type of mesh because of subsequent failures. Other graft materials that are discussed later in this chapter may have more promise, but long-term outcome data are lacking. Fascial autologous grafts, allografts, xenografts, and newer synthetics are presently used by many surgeons with variable short-term success and, thus far, little data on adverse effects and success after 3 years. These have been used in several ways in the anterior compartment, including placement of smaller grafts to bolster suture lines and larger grafts for complete substitution of the entire anterior support plate from the pubis to the arcus to the vaginal apex.

surgeons have abandoned this type of mesh because of subsequent failures. Other graft materials that are discussed later in this chapter may have more promise, but long-term outcome data are lacking. Fascial autologous grafts, allografts, xenografts, and newer synthetics are presently used by many surgeons with variable short-term success and, thus far, little data on adverse effects and success after 3 years. These have been used in several ways in the anterior compartment, including placement of smaller grafts to bolster suture lines and larger grafts for complete substitution of the entire anterior support plate from the pubis to the arcus to the vaginal apex.

Vaginal Paravaginal Repair

The paravaginal or “lateral defect” repair described first by White and reintroduced by Richardson and Edmonds involves reattachment of the anterior lateral vaginal sulcus to the obturator internus fascia and, at times, muscle at the level of the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis (ATFP) or “white line.” The paravaginal repair reattaches the anterolateral vaginal sulcus to the pubococcygeus and obturator internus muscles and fascia at the level of the ATFP. The original transvaginal repair used bilateral incisions along the lateral vaginal sulci to expose the arcus tendineus. Three or four sutures were then placed from the ischial spine along the ATFP to suspend the vaginal muscularis and adventitia bilaterally.

Subsequently, use of a midline incision was described that facilitated the concurrent repair of central anterior defects. The typical vaginal paravaginal procedure involves the “three point closure” with incorporation of the detached edge of the pubocervical connective tissue into the ATFP and the anterior vaginal wall with a series of four to six nonabsorbable sutures (Prolene, Ethicon, Somerville, NJ) 1.5 cm apart, initiated approximately 1 cm anterior to the ischial spine. The sutures are tied sequentially, beginning with the one closest to the spine and ending periurethrally. Cystoscopy should be performed to ensure ureteral patency and inadvertent stitch placement into the bladder. This often is performed with a reinforcement of the midline pubocervical connective tissue with trimming of the vaginal epithelium (if necessary) and closure. The procedure has been described with the use of a Capio suturing device as well (Microvasive Endoscopy, Natick, MA).

Observational outcome studies have reported good success (80% to 95%); however, long-term data on durability and function is lacking. Previous work has shown that most subjects with anterolateral detachments almost always have separation of the upper vaginal fornices from the arcus tendineus immediately adjacent to the ischial spine. Thus, it is important to resuspend those specific areas.

It is the authors’ opinion that it is difficult to achieve optimal results when vaginal paravaginal repair is used in combination with traditional central repairs because of the creation of tension on opposing suture lines. A repair that removes a weakened central vaginal wall may decrease the side-to-side dimensions of the anterior vaginal wall, making it difficult to suspend its lateral points more laterally. When large central defects are coexistent with lateral defects, one option is an extensive central repair accompanied by a good apical support procedure. This changes the shape of the vagina to a more cylindrical structure. Another choice is placement of a graft material to span the entire anterior rhomboid-shaped plate, thus augmenting anterior paravaginal tissue strength. The graft with tension adjusted may be anchored to the arcus tendineus along with the adjacent vaginal wall from the level of the pubic rami to the ischial spine. The new synthetic graft kits utilize this principle, as described later.

Although most reports indicate that repair of anterior defects with all of these procedures relieves symptoms that are directly related to prolapse, there is very little data on patient satisfaction and quality-of-life improvement over time. Such studies are much needed. There are no randomized trials that compare outcomes after anterior colporrhaphy versus vaginal paravaginal repair.

Posterior Compartment

There is no consensus on what defines a rectocele or posterior vaginal wall prolapse by physical examination or the use of diagnostic imaging modalities. However, early descriptions of the traditional posterior colporrhaphy in the early 1800s addressed perineal tears sustained at vaginal delivery. The support of the rectum and posterior vagina includes the pelvic floor musculature, connective tissue, Denonvilliers (pararectal) fascia (which is the fibromuscular layer of the posterior vaginal wall), and its lateral attachments to the lateral pelvic floor (levator) musculature and its fascia. This lateral attachment site, the fascia levator ani, fuses with the ATFP at the mid to upper vaginal level and continues to the level of the ischial spine. Less dense, areolar, connective tissue surrounds the rectum and vagina and may supply some fixation of these structures as well. Richardson hypothesized, based on careful cadaveric dissections, that most rectoceles were due to discrete tears in the Denonvilliers fascia at its lateral, apical, and perineal attachments and centrally within the fascia itself. He described perineal detachment along with a defect in the perineal membrane as a perineal rectocele, which is most commonly associated with complaints of difficulty with defecation. The apical attachment defects are generally associated with enteroceles and occasionally sigmoidoceles.

Once a decision is made to perform surgical repair of the posterior compartment based on symptoms, type, and location of defects, an appropriate approach should be decided on, and the patient should be made aware of what outcome she should expect and of potential adverse effects such as pain and sexual dysfunction. If the patient has defecatory dysfunction with a rectocele and has symptoms of constipation, pain with defecation, fecal or flatal incontinence, or any signs of levator spasm or analismus, appropriate evaluation and conservative management of

concurrent problems should be initiated prior to repair of the rectocele.

concurrent problems should be initiated prior to repair of the rectocele.

Specific types of repairs include the traditional posterior colporrhaphy, the defect-directed repair, replacement of fascia with graft materials, transanal repairs, and abdominal approaches by laparotomy or laparoscopy. An elegant review by Cundiff and Fenner has recently summarized data on the evaluation and treatment of women with rectocele, with a focus on associated defecatory and sexual dysfunction. Surgical outcomes with available objective and subjective measures were also reported.

Traditional Posterior Colporrhaphy

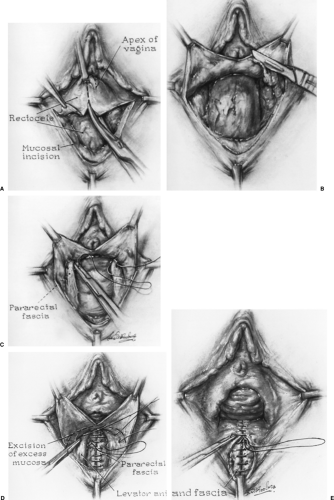

The first description of the posterior colporrhaphy was by Jeffcoate in 1959 and involved plication of the pubococcygeus muscles across the anterior rectum as well as perineal body reconstruction. Since that time, the technique has been modified in attempts to preserve sexual function. Typically, a midline incision is extended from the perineal body to the vaginal apex or to the cephalad border of a small or distal rectocele. The Denonvilliers fascia is mobilized from the vaginal epithelium, leaving as much of this tissue attached laterally to the levator fascia as possible.

After obvious defects in the rectal muscularis are repaired, the fascia is then plicated in the midline with interrupted or continuous sutures (Fig. 49.2). The authors prefer delayed absorbable suture, no. 1–0 or no. 0 polydioxanone, for this plication. Permanent nonbraided suture material may be used as well. In our experience, braided permanent suture material is subject to a greater incidence of stitch infection and formation of granulation tissue. The vaginal epithelium is trimmed and closed with absorbable sutures.

After obvious defects in the rectal muscularis are repaired, the fascia is then plicated in the midline with interrupted or continuous sutures (Fig. 49.2). The authors prefer delayed absorbable suture, no. 1–0 or no. 0 polydioxanone, for this plication. Permanent nonbraided suture material may be used as well. In our experience, braided permanent suture material is subject to a greater incidence of stitch infection and formation of granulation tissue. The vaginal epithelium is trimmed and closed with absorbable sutures.

When there is a defective perineal body or perineal membrane, reconstruction is performed after accompanying posterior colporrhaphy. The superficial muscles of the perineum and bulbocavernous fascia are plicated in the midline by using delayed absorbable suture, and the skin closed as in an episiotomy repair. Detachments of the inferior portion of the Denonvilliers fibromuscular connective tissue from the perineal body are also corrected. Plication of the puborectalis muscles concurrently with these procedures is performed by some surgeons in all or selected cases, but because this has been associated with a high incidence of sexual dysfunction, the authors do not recommend that it be performed routinely. However, puborectalis plication will be performed in selected patients with severe prolapse accompanied by a large genital hiatus with palpable levator weakness or inability to contract pelvic floor muscles. Sutures are carefully placed through the puborectalis muscles at least 3 cm or greater posterior to their insertion on the pubic rami, thereby decreasing the tension of the plication. For those women who desire sexual function with findings of an enlarged hiatus and weakened puborectalis muscles, there is an attempt to plicate the muscles far enough posteriorly to easily allow two fingers through the vaginal introitus and reconstruct the distal posterior vagina and perineum so that there will not be a ledge or ridge at the site of the puborectalis plication. Outcome data on such procedures is inadequate to make conclusions regarding its efficacy; however, it is the authors’ opinion that pelvic floor defects producing an enlarged genital hiatus are common reasons for failure of support procedures and that puborectalis plication may decrease the incidence of such failures.

Reported anatomic cure rates for traditional posterior colporrhaphy have ranged from 76% to 90% with variable follow-up. Most studies show a benefit to ease of defecation if patients are using preoperative splinting; however, overall defecatory dysfunction (defined as constipation) is usually not relieved in the majority of the subjects. These repairs, per se, also appear to be of little to no benefit to fecal incontinence. It is not surprising that the repairs are not particularly effective for defecatory dysfunction related to disorders of constipation or for fecal incontinence since the etiology of these problems are multifactorial. De novo dyspareunia is reported to occur in up to 25% of sexually active patients who have traditional posterior colporrhaphy and is not always associated with levator plication

procedures. Potential causes for dyspareunia other than vaginal strictures or introital tightness include scarring with immobility of the vaginal wall, levator spasm, and neuralgias associated with sutures and/or dissection. Dyspareunia may also occur when a Burch colposuspension procedure (or other procedures that cause anterior displacement of the vaginal canal) is combined with a posterior repair. Careful surgical technique and appropriate choice of procedure should decrease the incidence of postoperative dyspareunia.

procedures. Potential causes for dyspareunia other than vaginal strictures or introital tightness include scarring with immobility of the vaginal wall, levator spasm, and neuralgias associated with sutures and/or dissection. Dyspareunia may also occur when a Burch colposuspension procedure (or other procedures that cause anterior displacement of the vaginal canal) is combined with a posterior repair. Careful surgical technique and appropriate choice of procedure should decrease the incidence of postoperative dyspareunia.

Defect-specific Posterior Colporrhaphy

Defect or site-specific posterior repairs are restorative procedures by which the posterior defects described by Richardson are corrected. These repairs begin by midline posterior vaginal incision through the epithelium and then separation of the epithelium from the fibromuscular wall (Fig. 49.3). After irrigation for better exposure, a finger is inserted in the rectum to better define defects of the rectal wall and in the fibromuscular connective tissue layer that has been dissected from the vaginal wall subepithelium. The specific defects are closed with either interrupted or running sutures (the authors prefer the delayed absorbable type). Defect closure is accomplished in such a way to minimize tension on the surrounding tissue and may involve vertical, horizontal, or oblique approximation. When there is separation of the fibromuscular tissue from the perineum, the upper anterior rectum, or a well-supported cervix or vaginal cuff, it is important to reapproximate these connections. Repairs of coexistent perineal and apical support defects are important. The goal of the surgery is to re-establish an intact plane of connective tissue that positions the rectum against the pelvic floor and obliterates any potential space between a well-supported cervix or vaginal cuff and the cephalad edge of the tissue plane and upper rectum. The technique should minimize tension and avoid potential strictures, which may be more likely to occur with traditional posterior colporrhaphy.

Just as in anterior compartment procedures, the placement of graft materials to improve the success of posterior compartment repairs has been employed. Kohli and Miklos describe the use of a dermal allograft to augment

defect-directed repairs whereby the graft is sutured to the levator fascia on both sides of the defect to cover the rectovaginal plane. One concern about this technique is that in patients with relatively thin vaginal walls, removal of the fibromuscular tissue may devascularize the epithelium and make it more subject to erosion over the graft material. To improve the quality of vaginal epithelium in women with vaginal atrophy, patients in the authors’ practice use vaginal for 4 to 8 weeks preoperatively. The initial surgical dissection is deep to the fibromuscular layer. Access to the lateral levator fascia is generally easily accomplished with a division of the Denonvilliers fascia at its incorporation into the posterior vaginal wall or, if the lateral attachment is not present, with combined sharp and blunt dissection to expose the paralevator fascia. This levator fascia on each side as well as any remaining lateral Denonvilliers fascia and occasionally muscle is incorporated into the edge of the graft with sutures. The posterior cephalad edge of the graft is attached to the anterior rectum at its sigmoid junction, and the anterior cephalad edge is attached to a well-suspended vaginal cuff. The caudad edge is incorporated in an appropriate repair of the perineal area. With short-term, mean follow-up of 12 to 30 months, overall results reveal good anatomic cure rates of 89% to 100% with cadaveric dermis, autologous dermis, polyglactin mesh, and polypropylene mesh. Improvement in obstipation has also been reported. Although the numbers of subjects assessed have been relatively low, de novo dyspareunia rates have been between 0% and 7%.

defect-directed repairs whereby the graft is sutured to the levator fascia on both sides of the defect to cover the rectovaginal plane. One concern about this technique is that in patients with relatively thin vaginal walls, removal of the fibromuscular tissue may devascularize the epithelium and make it more subject to erosion over the graft material. To improve the quality of vaginal epithelium in women with vaginal atrophy, patients in the authors’ practice use vaginal for 4 to 8 weeks preoperatively. The initial surgical dissection is deep to the fibromuscular layer. Access to the lateral levator fascia is generally easily accomplished with a division of the Denonvilliers fascia at its incorporation into the posterior vaginal wall or, if the lateral attachment is not present, with combined sharp and blunt dissection to expose the paralevator fascia. This levator fascia on each side as well as any remaining lateral Denonvilliers fascia and occasionally muscle is incorporated into the edge of the graft with sutures. The posterior cephalad edge of the graft is attached to the anterior rectum at its sigmoid junction, and the anterior cephalad edge is attached to a well-suspended vaginal cuff. The caudad edge is incorporated in an appropriate repair of the perineal area. With short-term, mean follow-up of 12 to 30 months, overall results reveal good anatomic cure rates of 89% to 100% with cadaveric dermis, autologous dermis, polyglactin mesh, and polypropylene mesh. Improvement in obstipation has also been reported. Although the numbers of subjects assessed have been relatively low, de novo dyspareunia rates have been between 0% and 7%.

Transanal Rectocele Repair

The aim of transanal rectocele repair, usually performed by colorectal surgeons rather than gynecologists, is to remove or plicate redundant rectal mucosa, to decrease the size of the rectal vault, and to plicate the rectal muscularis, rectovaginal adventitia, and septum. Since the vaginal

epithelium is not incised or excised, this probably accounts for the procedure’s reported lack of adverse affects on sexual function in contrast to the vaginal approach to posterior repair. Two randomized trials and several case series from transanal repairs with mean follow-up of 12 to 52 months report anatomic cure rates of 70% to 98%, improved constipation and fecal incontinence, and less need for vaginal digitation to expel stool. Complications included infections and rectovaginal fistulas, which were surprisingly rare in the reported series. From the gynecologic perspective, transanal posterior repair only makes sense when the procedure is performed for defecatory dysfunction and not for prolapse of the posterior vaginal wall. It is unclear whether the transanal approach with defect excision and repair improves defecatory dysfunction better than a defect-specific transperineal or transvaginal approach with imbrication of tissues to correct palpable weakness in the rectal wall and its adjacent connective tissues.

epithelium is not incised or excised, this probably accounts for the procedure’s reported lack of adverse affects on sexual function in contrast to the vaginal approach to posterior repair. Two randomized trials and several case series from transanal repairs with mean follow-up of 12 to 52 months report anatomic cure rates of 70% to 98%, improved constipation and fecal incontinence, and less need for vaginal digitation to expel stool. Complications included infections and rectovaginal fistulas, which were surprisingly rare in the reported series. From the gynecologic perspective, transanal posterior repair only makes sense when the procedure is performed for defecatory dysfunction and not for prolapse of the posterior vaginal wall. It is unclear whether the transanal approach with defect excision and repair improves defecatory dysfunction better than a defect-specific transperineal or transvaginal approach with imbrication of tissues to correct palpable weakness in the rectal wall and its adjacent connective tissues.

Apical Compartment

Apical vaginal prolapse encompasses the findings of uterine prolapse with or without enterocele and vaginal vault prolapse but typically with enterocele. Defects in apical support include the loss of cardinal–uterosacral support with resultant cervical–uterine or vaginal cuff descent; the detachment of the fibromuscular vagina from the anterior rectum with resultant enterocele or, at times, sigmoidocele into the rectovaginal space; and tears or attenuation of the upper fibromuscular tissue usually posthysterectomy, leading to a central apical descent that frequently presents as a ballooning defect. Often, these defects occur concurrently. The general principles of the repair should include management of the specific apical defects: (a) if present, the attenuated part of the upper vaginal wall (fibromuscular defect) should either be repaired or covered by graft material; (b) the vaginal cuff, or in some instances the cervix, should be suspended without excessive tension; and (c) any defect in the attachment of the upper vagina to the rectum at or below its sigmoid junction should be corrected. Enterocele repairs may include (a) removal of the peritoneal sac with closure of the peritoneal defect and then closure of the fascial and/or fibromuscular defect below it, (b) dissection and then reduction of the peritoneal sac and closure of the defect, or (c) obliteration of the peritoneal sac from within with transabdominal Halban- or Moschowitz-type procedures or transvaginal McCall or Halban procedures. Historically, the “standard” for the treatment for symptomatic uterine prolapse has been hysterectomy, which is performed vaginally or abdominally in combination with an apical suspension procedure and repair of coexisting defects.

Apical support procedures that have been described for use when the uterus or cervix is to be kept in place include the Manchester-Fothergill procedure, described later, and the Gilliam procedure, which suspended the uterus with the round ligaments. The latter has been abandoned due to high rates of failure. In addition, fixation of the cervix to the sacrospinous ligament, uterosacral ligament plication, and fixation of mesh from the cervix to the sacrum (mesh sacral hysteropexy) have been described. Adequate outcome data on such uterine-sparing procedures are not yet available. One randomized trial in Europe compared Gortex sacral hysteropexy to vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension without mesh. The authors found higher failure rate and reoperation rate among the group who had uterine conservation with mesh sacral hysteropexy.

When the cervix is absent, it is the authors’ opinion that in addition to repair of fibromuscular defects, both fibromuscular planes anterior and posterior to the vaginal cuff should be attached to whatever suspension is employed.

Enterocele Repair

Enterocele repair usually is performed in the setting of concomitant procedures for prolapse, more often as related to posterior compartment repair and apical repair. Whether by vaginal, abdominal, or laparoscopic access, the enterocele repair is traditionally performed by sharply dissecting the peritoneal sac from the rectum and bladder. A purse-string suture can be used to close the peritoneum as high (cephalad) as possible; whether excision of the peritoneum itself is necessary has not been determined. Care must be taken to identify and avoid the ureters during peritoneal closure. More important than closing the enterocele sac is approximating the anterior to the posterior fibromuscular connective tissue of the vagina. Suspension of the vaginal apex is almost always necessary except in those rare cases when the enterocele occurs in the presence of adequate apical support.

Sacrospinous Ligament Suspension

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree