Operative Injuries to the Ureter

E. James Wright

Victoria L. Handa

DEFINITIONS

Cystotomy—Incision into the urinary bladder.

Psoas hitch—A technique to facilitate repair of mid- and distal ureteral injuries. The bladder is mobilized and anchored to the ipsilateral psoas muscle to facilitate tension-free ureteroneocystostomy.

Spatulate—To incise the cut end of a tubular structure longitudinally and splay it open to allow creation of an elliptical anastomosis of greater circumference than would be possible with conventional transverse or oblique end-to-end anastomoses.

Tampon test—A test used to differentiate vesicovaginal from uterovaginal fistula in the setting of postoperative vaginal fluid leak. Saline colored with methylene blue dye is instilled into the bladder and a tampon inserted into the vagina. If the tampon is unstained, a ureteral injury is suspected.

Ureteroileoneocystomy—Restoration of continuity of the urinary tract by anastomosis of the upper segment of the ureter to a segment of ileum, the lower end of which is then implanted into the bladder.

Ureteroneocystostomy—Reimplantation of the ureter into the bladder.

Ureteroureterostomy—Anastomosis between two segments of the ipsilateral ureter. When done between contralateral ureteral segments, this is termed transureteroureterostomy.

Urinoma—A fluid collection containing urine.

Ureteral injuries have been recognized as a potential complication of gynecologic surgery since the inception of our discipline. Over the years, numerous unique surgical modifications of procedures have been offered with the specific intent of decreasing the probability of ureteral injury. Despite these efforts, ureteral injury remains a very real complication of abdominal-pelvic surgery in the female patient.

The incidence of ureteral injury during gynecologic surgery is commonly cited as 1% to 2%, although the incidence varies with the nature of the surgery, the skill of the surgeon, and the complexity of the patient’s anatomy. Ibeanu and colleagues reported injury to the ureter in 15 of 839 hysterectomies performed at a teaching hospital in which universal cystoscopy was employed (incidence 1.8%, 95% confidence interval: 1.0%, 2.9%). Therefore, it is important for the gynecologic surgeon to be cognizant of ways to minimize the occurrence of this potentially disastrous complication, and to be facile in the diagnosis and management of such an injury should it occur.

The goals of this chapter are to (a) outline the functional anatomy of the ureter and illustrate how this leads to the ureter being in harm’s way during gynecologic surgery, (b) review the unique issues surrounding ureteral injury during the performance of specific groups of gynecologic surgical procedures, and (c) summarize the basic principles of injury avoidance and, should injury occur, recognition and management.

FUNCTIONAL ANATOMY OF THE URETER

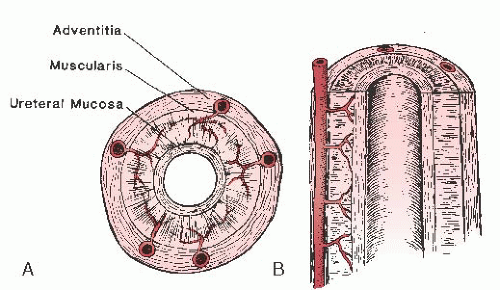

When viewed in cross section, the ureter can be divided into distinct layers: the lumen with transitional epithelium; the mucosa—the muscular layer—which is made up of longitudinal, circular, and spiral smooth muscle fibers; and the adventitia, which contains an intercommunicating network of blood vessels (Fig. 42.1). The peritoneum lies over the ureter, making it a completely retroperitoneal structure.

In normal adults, the ureter is between 25 and 30 cm in length from the renal pelvis to the trigone of the bladder. By convention, the pelvic brim divides the ureter into the abdominal and pelvic segments; each of these components is approximately 12 to 15 cm in length.

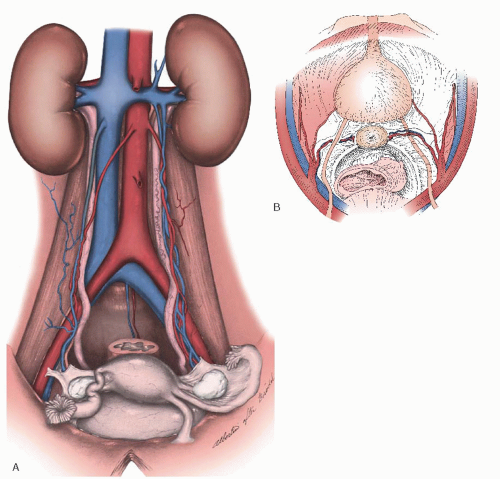

The abdominal ureter runs along the ventral surface of the psoas muscle and posterior to the ovarian vessels to the level of the pelvic brim. The right ureter lies slightly lateral to the inferior vena cava and descends into the pelvis over the common iliac artery at approximately the site of the latter’s bifurcation. In rare instances, the right ureter can be over the vena cava; therefore, if one is performing a paraaortic node sampling, the ureter must be identified before removing any nodes. The left ureter runs lateral to the aorta and posterior to the inferior mesenteric artery, ovarian vessels, and colon. The left ureter mirrors the right at the pelvic brim, entering the pelvis over the bifurcation of the left common iliac artery (Fig. 42.2). The left ureter is commonly obscured by the sigmoid colon at the pelvic brim.

There is little variance between the positions taken by the pelvic ureters. They descend into the posterior lateral pelvis

lateral to the sacrum and immediately ventral to internal iliac (hypogastric) artery. The ureters then course medial to the internal iliac artery and its anterior branches. The ureters subsequently pass beneath the uterine artery (often referred to as water under the bridge). The ureter is approximately 1.5 cm lateral to the cervix where it enters the paracervical tissues. The ureter passes through this paracervical tissue, often referred to as “the tunnel” of the cardinal ligament/anterior bladder pillar (also referred to as the web or the tunnel of Wertheim). Once through this tunnel, the ureter travels medially and anteriorly over the vaginal fornix to enter the trigone of the bladder.

lateral to the sacrum and immediately ventral to internal iliac (hypogastric) artery. The ureters then course medial to the internal iliac artery and its anterior branches. The ureters subsequently pass beneath the uterine artery (often referred to as water under the bridge). The ureter is approximately 1.5 cm lateral to the cervix where it enters the paracervical tissues. The ureter passes through this paracervical tissue, often referred to as “the tunnel” of the cardinal ligament/anterior bladder pillar (also referred to as the web or the tunnel of Wertheim). Once through this tunnel, the ureter travels medially and anteriorly over the vaginal fornix to enter the trigone of the bladder.

When inflammatory or adhesive changes are not present, the ureters can usually be visualized through the peritoneum from the pelvic brim to this parametrial tissue. Once the ureters have entered this tunnel, they cannot be easily seen or palpated; if identification is required, they must be mobilized out of this tissue. Although the peristaltic activity that occurs in the normal ureter may be helpful in its identification, it is not uncommon that the ureter, following any degree of trauma, will have transient paralysis. Therefore, the skill of accurately identifying the ureter is based on understanding its anatomy, not its motion. The ureter is unique in that it has a “snap” feeling when passed between the fingers during laparotomy. This may be helpful in massively obese women with poor exposure. This “snap” will also permit one to follow the ureter to the tunnel without actually exposing it. This technique is not applicable to laparoscopic or robot-assisted procedures. In these cases, identification of the ureter is enhanced by camera magnification but may require surgical exposure for confirmation of its course. Having defined the general anatomy of the ureter, one must appreciate that there is a significant degree of interpatient variability, even in a pelvis free of inflammatory, infectious, neoplastic, congenital, or postsurgical changes. Direct visualization of the ureter is the only sure way to know its location in any given patient.

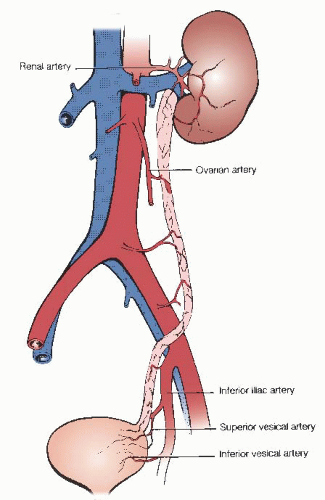

Along its course, the vascular supply of the ureter is derived from a variety of sources. Above the pelvic brim, the blood supply of the ureter is derived from medial vessels; more distally, the blood supply originates laterally (Fig. 42.3). Thus, cephalad to the pelvic brim, dissection and mobilization of the ureter should be approached from its lateral aspect, and the converse is true distal to the pelvic brim. The ureter is perfused by a rich network, with anastomoses within the adventitial sheath. The ureter is therefore relatively resistant to devascularization. However, such injuries may occur and can be difficult to diagnose, as the sequelae may not be apparent until the postoperative period.

INJURY TO THE URETER IN GYNECOLOGIC SURGERY

Hysterectomy

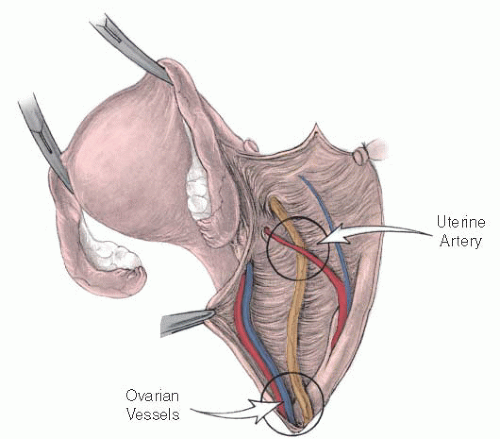

The ureter is vulnerable to injury during hysterectomy when the uterine artery is divided (Fig. 42.4). This is because the ureter passes under the uterine artery, lateral to the uterosacral ligaments, as it travels medially and ventrally to terminate in the bladder. The risk of injury to the ureter can be minimized by careful dissection of the bladder off the cervix, by upward traction on the uterus during the placement of clamps, and by clamping the uterine artery immediately along the cervix (rather than more laterally). At the conclusion of hysterectomy, the surgeon should be particularly vigilant when addressing bleeding from pedicles, especially at the vaginal angles. Bleeding from the pedicles or vaginal angle should be controlled by a “superficial” 3-0 suture so as not to incorporate the ureter.

Hysterectomy in the setting of cervical or broad ligament fibroids can be particularly challenging. The ureter can be anterior, lateral, or posterior to the fibroid. Clamping pedicles around the fibroid imposes significant risk for ureteral injury. In such cases, it may be prudent to perform a myomectomy by incision adjacent to the uterus or cervix. This can be done without risk of ureteral injury by staying within the myometrial capsule of the fibroid. Bleeding may occur, but once the fibroid is out, such bleeding is easily controlled by clamping adjacent to the uterus. In the rare case when this is impossible, the entire course of the ureter must be identified before clamping or cutting.

Ureteral injury during vaginal hysterectomy is remarkably uncommon. To some extent, this may be because vaginal hysterectomy is not typically performed for conditions most likely to distort ureteral anatomy, such as endometriosis or malignancy. In addition, the risk of ureteral injury is reduced during vaginal hysterectomy (compared to abdominal hysterectomy) because traction on the cervix pulls the uterus farther from the ureter. Tension on the cervix is therefore critical during the clamping of pedicles.

Ureteral injuries that occur during laparoscopic hysterectomy may be the result of thermal injury. When performing laparoscopic hysterectomy, it is imperative to know the location of the ureter. It can usually be visualized through the peritoneum; when not visible, it should be identified retroperitoneally and followed to the site of operative interest. Extreme caution should be used with cautery near or over the ureter, as thermal spread can cause occult injury that does not become apparent until 2 to 5 days after surgery.

Adnexal Surgery

Ureteral injury at the time of adnexectomy is worthy of specific comment. Especially in cases of an adnexal mass and distortion of the anatomy, the ureter is particularly vulnerable and it is in this setting that the ureter is commonly injured. These injuries can be avoided by using a retroperitoneal approach.

Every pelvic surgeon must be able to quickly and safely enter the retroperitoneum (which continues deep into the pelvis as the pararectal space). This surgical skill is necessary to (a) access the pelvic vessels for the purpose of establishing hemostasis and (b) use the retroperitoneum as an adhesion- and pathology-free “space” in which to operate. Access is obtained most commonly for the latter purpose. Once this retroperitoneal space has been developed, the ureter should be visible on the medial leaf of the broad ligament.

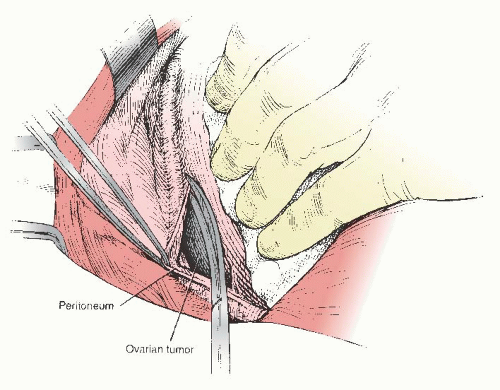

FIGURE 42.5 The ureter is dissected away from the peritoneum to permit resecting of ovarian mass/remnant. |

If an adnexal mass is adherent to the peritoneum overlying the ureter, the ureter can safely be dissected from the peritoneum. Distal to the pelvic brim, the dissection should be approached from the medial aspect of the ureter to minimize the risk of devascularizing the ureter. Once the ureter has been mobilized and is out of harm’s way, resection of the mass and the inflamed, scarred, or fibrotic peritoneum can be performed safely (Fig. 42.5). There are rare instances when it is impossible to mobilize the ureter from the pathology. In this setting, the surgeon must decide whether to leave residual tissue on the ureter (risking subsequent ureteral obstruction) or to resect a segment of ureter and repair accordingly.

Retropubic Surgery

Injury to the distal ureter may occur with high elevation of Burch colposuspension sutures. The ureter may also be injured by excessive lateral mobilization of the bladder. Mobilization exposes the dorsal surface of the bladder in the vicinity of the trigone and may bring the ureter into the operative field.

There are specific steps that can be taken to avoid such injuries. Dissection into and through the space of Retzius should be done under direct visualization, remaining as close to the symphysis pubis as possible. The amount of dissection that occurs over the lateral paravaginal tissues should be kept to the minimal amount needed to guarantee accurate and appropriate placement of the sutures. Finally, the urethrovesical junction must not be elevated excessively as this can cause kinking not only of the urethra but also the ureters in certain patients.

Surgery for Pelvic Organ Prolapse

The ureter may be ligated or kinked with surgery to correct prolapse. The risk appears to be highest with uterosacral ligament suspensions of the vagina. Barber and colleagues

reported ureteral obstruction in 11% (5/46) of cases (treated with release of the suspension sutures or ureteral reimplantation). Karram and colleagues reported ureteral injury in 5/202 (2.4%), and Shull and colleagues reported ureteral injury in 3/302(1%).

reported ureteral obstruction in 11% (5/46) of cases (treated with release of the suspension sutures or ureteral reimplantation). Karram and colleagues reported ureteral injury in 5/202 (2.4%), and Shull and colleagues reported ureteral injury in 3/302(1%).

Anatomic studies by Buller and colleagues demonstrated that the distance from ureter to uterosacral ligament is 4.1 ± 0.6 cm at the sacral origin of the uterosacral ligament, decreasing to 0.9 ± 0.4 as the uterosacral ligament approaches the cervix. Placement of the suspension sutures at or slightly above the level of the ischial spine (in the intermediate portion of the uterosacral ligament) is therefore recommended to minimize the risk of injury. Ureteral injury has also been reported with sacrospinous suspension, midurethral sling, and anterior colporraphy. Thus, confirmation of ureteral patency via cystoscopy should be routinely performed at the conclusion of these procedures to verify ureteral integrity.

Radical Pelvic Surgery

Of all the groups of surgical procedures performed, those performed for the treatment of cancers affecting the female reproductive tract are the most likely to involve either intentional ureteral surgery or have the highest risk of an associated ureteral injury. It is important to differentiate between intentional ureteral disruption and unintended or inadvertent injury. The MD Anderson type IV radical hysterectomy, a total or anterior pelvic exenteration, and resection of a fixed pelvic sidewall mass involving the ureter may include ureteral resection and reconstruction by design. As a result of the nature of gynecologic malignancies and the procedures performed to treat those diseases, intentional and sometimes unintentional ureteral injuries occur. Additionally, the need to explore a radiated field, or one in which multiple operations have been performed, compounds cofactors that put the ureter at risk. It is evident that the surgeon must not only be expert in pelvic anatomy but also have the judgment to establish how and when to address a problem while minimizing the probability of injury.

How common are ureteral injuries in association with radical pelvic surgery? Recent data from the National Hospital Discharge Survey suggest that ureteral injury during radical hysterectomy occurs in 7.7 per 1,000 cases. Historically, the average rate of ureteral injury at the time of radical hysterectomy has approximated 1%, with a concomitant similar rate of bladder injury. Interestingly, these rates have been consistent over time and among different surgical groups. In contradistinction to these relatively low rates of ureteral injury, when radical resection is performed following radiation therapy there is an associated risk of ureteral dysfunction of approximately 30%. Ureteral injury associated with lymph node dissection or when performing “radical” oophorectomy is remarkably uncommon when those injuries occurring near the entrance to and through the tunnel of Wertheim are excluded from the data.

DIAGNOSING URETERAL INJURY

Diagnosis of Ureteral Injury during Surgery

As noted, pelvic surgery risks injury to the ureter at a number of sites along its course (Table 42.1). A clear understanding of ureteral anatomy and its potential variability is critical to avoiding injury. The surgeon should make a habit of confirming ureteral integrity during and at the conclusion of any pelvic procedure, regardless of whether the surgery is done by the vaginal, open, laparoscopic, or robot-assisted approach. This will require direct visualization of the ureter (or palpation, in the setting of laparotomy). For both open and laparoscopic procedures, opening of the parietal peritoneum may at times be necessary to allow for accurate inspection or to allow for mobilization and separation from the site of operative interest. This is especially important in the setting of inflammatory conditions such as endometriosis, malignancy, or adhesions from prior surgery.

TABLE 42.1 Common Sites of Ureteral Injuries | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|