Fig. 7.1

Sagittal view of enterocele in post-hysterectomy patient. (Reprinted with permission, Cleveland Clinic Center for Medical Art & Photography © 2009–2013. All Rights Reserved)

Given the results of the Colpopexy and Urinary Reduction Efforts (CARE) and Outcomes Following Vaginal Prolapse Repair and Midurethral Sling (OPUS) trials, all our patients are counseled on the probability of a concomitant anti-incontinence procedure at the time of POP surgery [17, 18].

Subsequently, all patients that have comorbidities such as coronary artery disease, obstructive sleep apnea, uncontrolled hypertension, diabetes, or symptoms suggesting non-diagnosed medical problems are referred to anesthesia for preoperative clearance. Prior to surgery, all patients are told to refrain from NSAIDs/blood thinners for up to 1 week prior to surgery date, a bowel preparation to decrease stool content in the pelvis region, and nothing by mouth after midnight. For patients who routinely smoke, we advise them to stop smoking to aid with recovery, wound healing, and also improve their general overall health. An informed consent is performed in conjunction with the patient and operating surgeon. Given the recent FDA announcements regarding transvaginal mesh, numerous questions can be expected given that ASC is most successfully performed with artificial synthetic graft material. It is important to note that the FDA announcement focuses on transvaginal mesh placement and addresses the need for further studies regarding transvaginal mesh placement for POP (Table 7.1). We do not routinely correct anterior/posterior compartment defects at the time of ASC but this should be individualized to each patient depending on goals and symptoms. Concomitant anti-incontinence procedures are typically performed with a mid-urethral sling utilizing synthetic macroporous polypropylene mesh, with efficacy and safety that have been demonstrated in long-term studies [19, 20].

Table 7.1

FDA safety communication

FDA safety communication: serious complications associated with transvaginal placement of surgical mesh for pelvic organ prolapse |

|---|

The FDA first released a notice in 2008 regarding the complications of transvaginal mesh placement for POP. In July 2011, an update was provided regarding transvaginal mesh usage in POP. Given the additional 2,874 reports of complications received from January 1, 2008 to December 31, 2010, they concluded that serious complications are not rare. While open ASC utilizes artificial synthetic mesh, this FDA notification does not apply specifically to transabdominal mesh placement for pelvic organ prolapse (see below). Although not specific to transabdominal mesh placement, this notice highlights the need for patient education and a thorough informed discussion process between the surgeon and patient regarding the realistic goals of treatment and the complications stemming from any surgery. The following is a summary of the recommendations for healthcare providers: |

• Obtain specialized training for each technique; be aware of the risks. • Be vigilant for potential adverse effects. • Watch for complications associated with tools used for mesh placement. • Inform patients of the permanency of mesh and that some complications may need additional surgery. • Inform patients that complications can affect their quality of life due to dyspareunia, scarring, and narrowing of the vagina. • Provide patients with a patient labeling from the mesh manufacturer. • POP can be treated without mesh. • Choose mesh after weighing the risks and benefits of all alternative options. • Consider the following before placing mesh: – Mesh is permanent making further surgery difficult. – Mesh may put the patient at risk for further surgery and the development of new complications. – Removal of mesh is difficult and may require multiple surgeries and poorer quality of life due to complications. – Mesh placed abdominally for POP repair may result in lower rates of mesh complications compared to transvaginal mesh. • Inform the patient about all options for POP including nonsurgical and non-mesh including the likely success of the alternatives. • Notify the patient if mesh will be used and what specific type. • Ensure the patient understands the risks and complications including the limited long-term data. |

Complications discussed with all patients include the risk of infection (UTI 10.9 %, wound infection 4.6 %) hemorrhage/transfusion 4.4 %, bladder/bowel or ureteral injury 1–3 %, DVT or PE 3.3 % [21]. Ileus and small bowel obstruction requiring reoperation are quoted at 6.9 % and 1.2 % respectively [22]. Extrusion rates with polypropylene mesh from 0.5 % to 10.5 % are quoted [21, 23, 24]. Subjective improvement based on global assessment is quoted upwards of 85 % [25]. Rates of reoperation for POP are expected to be less than 5 % in modern series but can be as high as 29 % [3, 21, 25].

Technique

The day of surgery, patients arrive in the preoperative care unit where an intravenous line is started by anesthesia. Perioperative antibiotics are administered within 60 min of the surgical incision. Given the intra-abdominal nature of the case, we prefer using cefazolin or clindamycin and gentamycin in patients who have a severe penicillin allergy or allergy to cephalosporins [26]. Subsequently the patient is positioned in the lithotomy position with a slight amount of flex to open the pelvis. We routinely utilize yellow fin stirrups for the legs. All pressure points are padded. Sequential compression devices are placed. The patient’s vagina and abdomen are prepped. Preoperatively a dose of prophylactic subcutaneous 5,000 units of heparin or 40 mg enoxaparin is administered.

The patient is then prepped and draped. A 16 fr Foley catheter is placed to empty the bladder. One may choose to make either a Pfannensteil or lower midline incision. Camper’s and Scarpa’s fascia are dissected through with electrocautery. The rectus is split in the midline. The peritoneum is opened close to the umbilicus. Any adhesions encountered are taken down sharply with metzenbaum scissors. Pelvic exposure is improved by using a self-retaining Bookwalter retractor and also packing the rectum to the patient’s left side. The anterior plane of the vagina is dissected away from the bladder. We find that utilizing an end-to-end anastamotic (EEA) sizer or sponge stick in the vagina helps in exposing the vagina and aiding with dissection. Only in extreme cases of scarring do we find it appropriate to backfill the catheter to find the bladder. Once the bladder has been dissected free from the vagina, the posterior vagina is addressed. The vagina is dissected free from the rectum. Again in conditions of extreme adhesion or uncertainty, do we find an additional EEA sizer useful for rectal delineation.

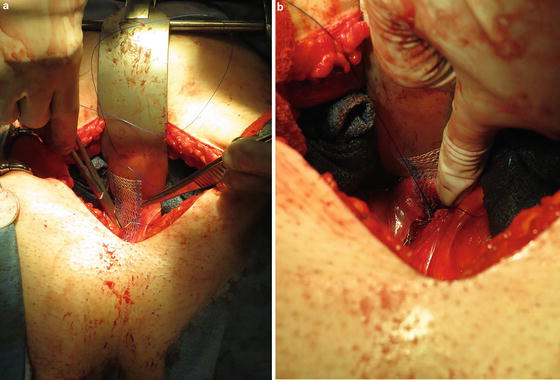

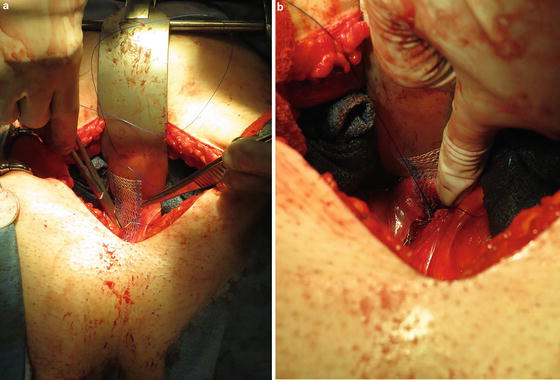

Once the anterior and posterior walls of the vagina are free, dissection of the anterior longitudinal ligament is performed. Care is taken to incise the peritoneum overlying the sacral promontory at the midline in a longitudinal fashion and avoid the iliac vessels. Bleeding in this area can be attributed to any number of vessels in the area including the middle sacral vessels and superior and inferior hypogastric plexus. In cadaveric studies, on average the left common iliac vein was the closest major vessel (2.2–2.7 cm) to the mid-sacral promontory while the middle sacral artery and vein were closer at less than a centimeter (Fig. 7.2) [27]. After the sacral promontory at the level of S1 is cleared off, two pieces of 3 cm × 15 cm macroporous synthetic polypropylene mesh are used for grafting. While many different biologic (fascia lata, rectus fascia, porcine dermis) and artificial synthetic grafts (polytetrafluoroethylene, polyester, polyethylene, silicone coated) have been used, we prefer to use polypropylene mesh given its efficacy and decreased rate of exposure/erosion (Fig. 7.3a, b) [28–32]. The polypropylene mesh is attached to the anterior and posterior vaginal wall using non-braided delayed absorbable suture such as polydioxanone. Alternatively, several permanent monofilament sutures can be utilized away from the anterior bladder dissection. The mesh is fixated at approximately 5 points along both the posterior and anterior vaginal walls. These are preferentially tied down with multiple knots given the location deep in the pelvis (Fig. 7.4). We have also utilized nonabsorbable braided suture for graft fixation, but patients may occasionally complain about continued vaginal discharge from suture exposure. Multiple studies have suggested a higher rate of exposure/extrusion correlated with the use of braided suture material but they are limited by their small sample sizes, heterogeneous use of graft material, and retrospective nature. No prospective trial exists evaluating the risk associated with monofilament absorbable suture and braided suture on polypropylene mesh extrusion/erosion in ASC [29, 33, 34].

Fig. 7.2

Cadaver pelvic vascular anatomy dissection. Sacral venous plexus. Left common iliac vein (LCIV), internal iliac vein (IIV), middle sacral artery (MSA), middle sacral vein (MSV), midsacral promontory (asterisk), lateral sacral veins (arrows), and sacral venous plexus anastomoses (arrowheads). (Used with permission from Wieslander CK, Rahn DD, McIntire DD, Marinis SI, Wai CY, Schaffer JI et al. Vascular anatomy of the presacral space in unembalmed female cadavers. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 2006 Dec;195(6): 1736–41)

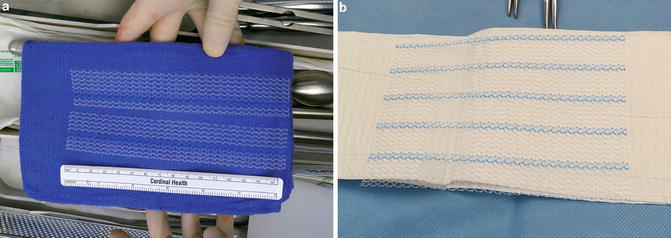

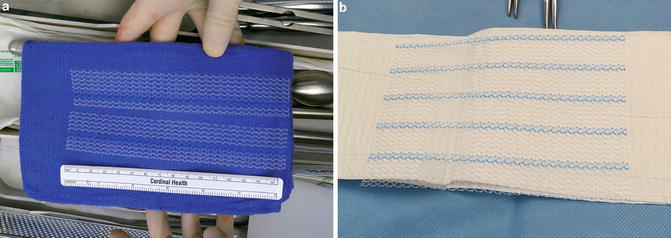

Fig. 7.3

Macroporous polypropylene synthetic mesh used for sacrocolpopexy. (a) Cut mesh. (b) Whole mesh

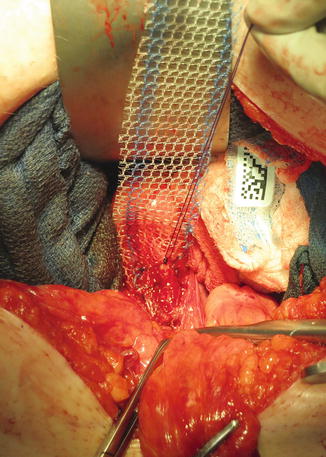

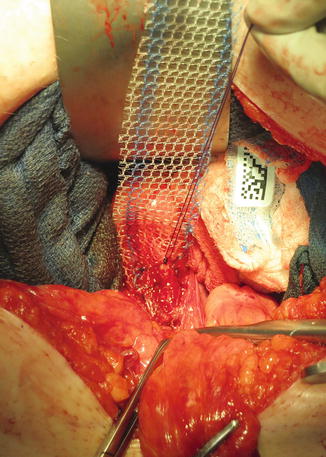

Fig. 7.4

Placement of mesh over the anterior portion of the vagina. We prefer to suture the mesh onto the anterior vagina with absorbable monofilament suture with multiple knots to secure the mesh deep in the pelvis

With an EEA sizer in the vagina to reduce the prolapse, the mesh tails are tensioned appropriately and fixated to the anterior longitudinal ligament. Tensioning should be done to assure at least mobility to the bladder neck and avoid undue tension so as to keep the vaginal axis straight, avoiding upwards deviation. The excess mesh is then trimmed. Our suture of choice for fixation to the sacral promontory is a non-braided permanent suture (Fig. 7.5a, b). Two sutures are placed in a horizontal fashion on the anterior longitudinal ligament. In a cadaveric study utilizing female non-embalmed specimens, horizontal versus vertical suture placement was not found to be statistically significant in regard to pull out strength in sutures placed at or 1 cm above the level of S1 [35]. Care should also be taken to place the suture in the anterior longitudinal ligament and not through the disc space which could lead to a potential space for infection/abscess. Risk can also be minimized by ensuring that the vaginal fixation sutures are not through the vaginal epithelium [36, 37].

Fig. 7.5

The tails of the mesh are sutured to the anterior longitudinal ligament using nonabsorbable monofilament suture

At this time, the peritoneum is reapproximated over the mesh. Although retroperitonealization of the mesh does not necessarily lead to fewer complications, reapproximation of the peritoneum adds little time and morbidity to the surgery [38]. If a large defect in the posterior cul-de-sac is seen, culdoplasty can be performed at this time. Anecdotally, given the advent of minimally invasive sacrocolpopexy, there has been a decrease in concomitant culdoplasty with minimal change seen in objective results. From below, the apical prolapse is reassessed to ensure the defect has been corrected. The anterior and posterior compartments are reassessed after ASC. Any anterior or posterior vaginal repairs are performed at this time. We do not routinely offer a posterior colporrhaphy to all prolapse patients and concomitant posterior colporrhaphy is based on the patient’s preferences and symptoms (Fig. 7.6).

Fig. 7.6

Sagittal view of ASC repair with synthetic mesh. (Reprinted with permission, Cleveland Clinic Center for Medical Art & Photography © 2009–2013. All Rights Reserved)

If an anti-incontinence procedure is to be performed, an assistant can begin with the vaginal dissection and exposure for a retropubic mid-urethral sling while the abdomen is being closed. Hemostasis is confirmed by visualization. The pelvis is irrigated with body temperature saline. All surgical counts are verified. The abdominal closure is done in a sequential fashion using #1 looped PDS for fascial closure. In obese patients, we prefer to re-approximate Scarpa’s fascia to avoid dead space. The skin is addressed with a running subcuticular stitch using polyglactin suture. Cyanoacrylate skin adhesive is used for the skin. The patient is woken up from anesthesia and monitored in the post-anesthesia recovery unit. All patients then transition to an acute surgical floor. Intravenous fluids are continued at maintenance rates until the patient is tolerating a diet. All patients are started on a prophylactic deep vein thrombosis regimen including early ambulation and subcutaneous heparin. On postoperative day 1, clears are started, the vaginal pack is removed and a trial of void is performed. Postoperative labs are not routinely checked after surgery unless bleeding occurred or a patient is symptomatic [39]. The patient is transitioned to oral pain medication when they are tolerating a diet. All patients receiving narcotics receive a stool softener to reduce the incidence of constipation. Postoperative length of stay is usually 2–3 days.

Patients are discharged from the hospital with postoperative instructions. All patients are told to refrain from heavy lifting greater than 10 lbs during this time period, avoid strenuous activity (although avoidance of any activity such as walking is contraindicated), avoid vaginal instrumentation/sexual intercourse. Follow-up is scheduled at 6 weeks. At the patient’s follow-up visit, we routinely perform a physical examination to assess for POP recurrence and graft exposure/extrusion.

Outcomes

Definition of Success

Success of ASC encompasses a heterogeneous definition of outcomes. Depending on whether success is defined by objective POP-Q postoperative evaluation versus patient satisfaction, effectiveness can range anywhere from 78 % to 100 % for apical prolapse versus 85–100 % for patient satisfaction [21]. In a randomized controlled study evaluating ASC to vaginal sacrospinous colpopexy, subjective success based on prolapse symptoms and satisfaction of ASC based on visual analog scale were 94 % and 85 %, respectively, at an average of 2 years [40]. In one of the longest follow-ups at a mean of 13.7 years, Hilger et al. demonstrated a 74 % success rate with ASC. Success in this study was defined by either no reoperation for POP or a negative answer to question 5 on the Duke Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory (“Do you usually have a bulge or something falling out that you can see or feel in the vaginal area?”) Although significantly long in follow-up, only 12 of the original 47 women included in the study were available for examination. Of those 12 women who were examined, 6 patients had failed by their criteria and none of the 12 had greater than stage II prolapse on examination [41]. At the time of writing this chapter, the latest update from the CARE trial with 7 year follow-up demonstrated an estimated anatomic failure rate of 27 % in the urethropexy arm versus an estimated symptomatic POP failure rate of 29 % in that same group. Anatomic failure was defined as reoperation or pessary for POP where the vaginal apex descends below the upper third of the vagina or the anterior/posterior vaginal wall descends past the hymen. Symptomatic failure was defined as a positive response to one or more questions on the POP distress inventory referring to seeing or feeling a bulge or reoperation or pessary for POP [24].

Attempting to address this obtuse definition of success in ASC patients, Barber et al. evaluated the data from the CARE trial and applied 18 different surgical success definitions. Among their objectives was to describe how using different definitions affect estimates of treatment success and compare different definitions of surgical success by examining their relationship to patient’s subjective assessments of improvement. At 2 years, 94 % of patients achieved surgical success when it was defined by absence of prolapse beyond the hymen. When applying National Institutes of Health definitions of outcomes such as optimal (POP-Q stage 0) or satisfactory (support higher than 1 cm proximal to hymen), the rates of success were lower at 19 % and 57 % [25].

Rates of reoperation for prolapse in the original CARE trial were low at 2.8 % over 2 years which rose to 5.1 % over the course of 7 years [24, 25]. This is comparable to the 4.4 % (0–18.2 %) median reoperation rate observed in summarized published studies. The most common reason for reoperation was for prolapse of the anterior or posterior compartment [21]. The longest follow-up was noted to be 3 years. Hilger et al. evaluating results at a mean of 13.7 years found a 10.5 % rate of reoperation for recurrence [41].

Genitourinary/Gastrointestinal/Sexual Function Outcomes

In regard to system specific genitourinary, gastrointestinal, and sexual function after ASC, most studies in the past did not evaluate complaints with standardized validated questionnaires or in prospective fashion thereby making a generalization on outcomes difficult to assess. In a case control study evaluating women who had undergone ASC versus women who had solely undergone hysterectomy, patients were evaluated using a bowel function questionnaire and the Cleveland Clinical Incontinence Score (CCIS). While those undergoing ASC had more significant obstructive defecatory symptoms (splinting, incomplete evacuation, use of enemas), fecal incontinence rates were not different. Incontinence was noted to be higher in patients who had obstetric anal injury. Unfortunately, results from this study are difficult to extrapolate without the context of preoperative symptom scores. On average, time from surgery to questionnaire was 8.1 years for the ASC group [42]. Evaluating 1 year bladder symptoms based on UDI changes in patients who participated in the CARE trial, de novo irritative voiding was reported in 12/131 (9.2 %) women. For those with obstructive voiding symptoms before surgery, improvement was noted in 85.1 %. A statistically significant mean reduction of PVR of 31 mL was observed postoperatively [43]. One year follow-up was also evaluated in regard to sexual function in patients who participated in the CARE trial. Using the Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Functioning Questionnaire (PISQ-12), patients who had a sexual partner before and after surgery were evaluated at 1 year for effects of surgery on sexual function. There was a statistically significant rise in the amount of women who were sexually active compared to prior to surgery (76.3 % vs. 66.1 %, p < 0.001). Fewer women after ASC avoided sexual activity due to pelvic or vaginal symptoms, fear of incontinence, bulge in the vagina, or being limited by pain. It was noted that 11/148 (7.4 %) women became sexually inactive after surgery. There was a higher proportion limited by pain but this was not statistically significant (26 % vs. 22 %, p = 1.0). The authors did note that there was a higher incidence of infrequent sexual desire amongst those who were inactive after surgery (70 % vs. 22.1 %, p < 0.001) [44].

Open ASC Versus Laparoscopic/Robot Assisted ASC

Although ASC has been recognized as the gold standard surgery for apical POP repair, increased hospital stay, blood loss, and length of recovery have all been listed as drawbacks of open ASC compared to other approaches [45]. Minimally invasive surgery and robot assisted laparoscopic surgery decrease the convalescence associated with transabdominal surgery. Siddiqui et al. evaluated robotic ASC outcomes at 1 year compared to patients in the CARE trial and found no significant difference in surgical failures as defined by bothersome vaginal symptoms or repeat surgery for prolapse (8 % vs. 4 %, p = 0.16). Operative characteristics that were significantly different between robotic vs. open ASC include estimated blood loss (90 mL vs. 228 mL, p < 0.01), concomitant hysterectomy (49 % vs. 28 %, p < 0.01), and posterior repair at time of ASC (8 % vs. 22 %, p < 0.01). Complications that were significantly different included wound disruption (0 % vs. 4.3 %, p = 0.01), febrile morbidity (4.8 % vs. 10.9 %, p = 0.04), and ileus (5.6 % vs. 11.6 %, p = 0.05) [46]. Rozet et al. similarly found laparoscopic sacral colpopexy to be efficacious in treating POP. The retrospective review evaluated 363 patients who underwent a laparoscopic sacral colpopexy. 25 % of patients had undergone a previous hysterectomy and only 4 % had a concomitant hysterectomy. Complications were low with 2 % requiring open conversion. Average hospital stay was noted to be 3.7 days. On average follow-up for 14.6 months, anatomic cure rate, which was not defined on postoperative visit, was noted to be 96 % with a similar 96 % satisfaction rate [47]. These rates are similar to a recent review article regarding laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy [48]. A retrospective cohort study evaluating laparoscopic and ASC found that although mean operating time (269 min vs. 218 min, p < 0.0001) was longer in the laparoscopy cohort, mean hospital stay was significantly shorter (1.8 days vs. 4 days, p < 0.0001). Clinical efficacy was difficult to assess given that not all patients had preoperative and postoperative POP-Q standardized scores [49]. To date no prospective randomized trial have been done to evaluate robotic ASC to open ASC [50].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree