Office Gynecology and Surgical Procedures

Marian D. Damewood

William R. Keye Jr.

Charles C. Coddington III

The number of women in the United States is approximately 153 million and increasing. Women in their reproductive years represent 49% of the total, with those under age 15 at 20% and those over 50 at 31%. The number of postmenopausal women is projected to increase to 52 million in 2010 and 62 million in 2020. The entire female population is estimated to grow over 17% in the next 20 years.

Gynecologists have a major role in the provision of health care for women, with changes in technology, patient expectations, office procedures, and health care delivery formats providing new challenges. The number, percentage, and characteristics of patients who receive care exclusively from gynecologists are increasing. Thus, the complexity and details of the gynecologic history and examination are of great importance in women’s health care. Gynecologic procedures that primarily were performed in the hospital setting can now be performed in the office, such as transvaginal ultrasound with saline infusion sonography (SIS), decreasing the number of hospital-based diagnostic procedures. These changes in the specialty of gynecology coupled with recent demands on the medical community for cost control has stimulated the trend for more outpatient care and office-based surgery. The technology to perform minor gynecologic surgical procedures in an office setting or procedure room is readily available. This chapter will discuss the gynecologic history and examination and review a number of procedures that may, with the appropriate facilities and patient selection, be performed in an office surgical setting.

Preventive Care

A great deal of gynecologic care is preventative and depends on population characteristics, risk profiles, epidemiology, and statistics for screening programs. Annual examinations may be recorded on data sheets containing “check-off” lists for preventive services. An example of this type of form is available at the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) website (http:// www.acog.com). Reminder systems for follow-up visits for Papanicolaou (Pap) smears and mammograms can help to integrate disease prevention and health maintenance into gynecologic practice. In addition, gynecologists play a major role in screening for domestic violence, depression, injury, and other psychosocial concerns as well as sexual dysfunction. Counseling practices for sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and human papillomavirus (HPV) infection has changed markedly over the past 2 decades.

In June 2006, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) licensed the first HPV vaccine developed to prevent cervical cancer and other diseases in females caused by HPV infection. The quadrivalent vaccine labeled as Gardasil® protects against four HPV subtypes (6, 11, 16, 18). These types are responsible for approximately 70% of cervical cancers and 90% of genital warts. Indications at this time include the use of this vaccine in females ages 9 to 26 years. Ideally, it should be administered before the onset of sexual activity but may be useful afterward as well. The vaccine has been tested in over 11,000 women worldwide, with studies noting that there are no serious side effects. Clinical trials have

demonstrated close to 100% efficacy in preventing cervical, vulvar, and vaginal precancers as well as genital warts caused by the four HPV types. If the patient is already infected by one of the HPV types, the vaccine will not prevent disease from that type but will prevent against the remainder. Current studies suggest that the vaccine is effective for at least 5 years.

demonstrated close to 100% efficacy in preventing cervical, vulvar, and vaginal precancers as well as genital warts caused by the four HPV types. If the patient is already infected by one of the HPV types, the vaccine will not prevent disease from that type but will prevent against the remainder. Current studies suggest that the vaccine is effective for at least 5 years.

Additional preventative measures include genetic screening for some forms of breast and ovarian cancer, which could result in the assimilation of routine genetics into gynecologic office practice. In addition, postmenopausal women have a variety of preventive health needs including breast and cervical cancer screening and primary care such as cholesterol screening and smoking cessation. This health care interaction begins with the gynecologic history and follows up with physical examination, along with office diagnostic procedures.

Medical History

Women who want to be actively involved in decisions regarding their gynecologic care usually expect physicians to use the history to obtain information concerning not only medical issues but also concerns regarding family history, cancer risk, sexual partners, or significant personal and social issues. The quality of the medical care provided by a physician, as well as the type of the relationship between the physician and patient, may be determined largely by the depth of the gynecologic history.

A comprehensive history and physical examination should be performed on each new patient. It is important to establish a database on each patient, along with a physician–patient relationship based on good communication. Scheduling should permit dedicated time for new patient bookings to allow sufficient time to obtain the information, perform an examination, provide the management plan, and allow for health education. Many preprinted history and physical examination forms exist, some of which may be obtained at the ACOG website, including the Women’s Health Record for initial and long-term follow up office care. Some physicians prefer to use patient-directed history forms, others use an assistant or nurse, and still others prefer to take the history personally. Multiple studies have documented that personally directed questioning is more productive than the use of patient questionnaires. Understanding the preventive medicine needs based on family history, patient history and lifestyle, and integrated functional medical investigations is important. The development of personal preventive programs impacts the ongoing health and wellness relationship.

Once a good database has been established, updates should include any changes in gynecologic or pregnancy history. Additional surgery, accidents, hospitalizations, new medications, or allergies should be added. Any changes in family history should be noted. This type of history taking, both for new and established patients, results in a well-organized, problem-oriented medical record. Besides obtaining the historical details, it is important to understand why the patient is seeking care in the gynecologist’s office. In addition to understanding and meeting patients’ needs, physicians must be prepared to do a medical evaluation in a physically and emotionally comfortable setting, making the visit as comfortable and informative as possible so that women leave the office calm and with their questions answered. This is achieved by an understanding attitude and an ability to listen.

Several things can be done when obtaining a history to reduce patients’ anxiety.

The history should be obtained in as comfortable and private a setting as possible. Many patients prefer to be clothed and seated at the same level as the physician, especially if they are meeting for the first time. Other patients may choose to change into an examination robe before seeing the physician if the visit is for a follow-up examination. Under most circumstances, patients should be interviewed alone. Exceptions may be made for children, adolescents, and mentally impaired women or at the specific request to have an attendant or a family member present. Even in these situations, it usually is a good idea to give patients the opportunity of speaking privately.

The initial portion of the interview should be designed to put patients at ease. This often can be accomplished by discussing neutral and nonmedical subjects, such as recent recreational activities, employment, and family. The discussion should be viewed not merely as a means of relaxing patients but also as an opportunity for gathering information about their psychologic and social backgrounds.

Physicians should not make assumptions about patients’ backgrounds. For example, a clinician usually assumes that all adult female patients are sexually active and heterosexual. Either assumption or both may be incorrect. By asking neutral, open-ended questions (e.g., “Are you sexually active?” and “Are you having sex with men?”), physicians let patients know that these assumptions have not been made.

An appropriate length of time should be scheduled to allow a patient to tell her story without being hurried or interrupted. Interruptions from phone calls or office staff should be avoided, if at all possible, so that the patient has the physician’s undivided attention.

Patients should be made to feel that they have the respect of the physician. This means that they will have the opportunity of sharing in the decision-making process, will not be forced to endure unwanted pain, will have what they tell the physician held in strict confidence, and are free to ask questions. Patient satisfaction is related to the

time required to get an appointment, the patient mix in the reception area, the length of waiting time in the reception or examination room, the attitude of the office staff, and the billing procedures.

In this age of rapidly expanding medical knowledge and an emphasis on preventive health care, it is ironic that there is widespread dissatisfaction in physician–patient relationships. There is increasing evidence that a physician’s attitude influences not only patient compliance but also the ultimate effect of therapy. The first step in effective communication is establishing a good physician–patient relationship. Research in human relations has demonstrated that a rapport is most readily established if physicians possess and display certain qualities including empathy, respect, non-possessive warmth, genuineness, non-judgmental acceptance, kindness, and interest. These qualities are common to all effective counselors and can be learned by most clinicians. They reinforce these qualities by summarizing their understanding of patients’ problems in terms that patients can understand. The communication of warmth, kindness, and interest is, for the most part, non-verbal. Examples of nonverbal communication that convey these qualities include maintaining eye contact, having a relaxed open posture, facing the patient, leaning toward the patient, showing a facial expression consistent with the patient’s predominant emotion, and having a modulated, nonmechanical tone of voice.

The history provides information about the total patient and is perhaps the most important part of the gynecologic evaluation. In most cases, it provides the data to establish a tentative diagnosis before the physical examination. If the gynecologic history is sufficiently comprehensive, it should in many cases permit a physician to narrow the likely diagnoses. Like a hospital chart, the office chart is a legal and medical record. As such, it is subject to subpoena, and whatever is recorded in it may someday need to be defended in court. It should not contain extraneous or casually entered material, and the notes should be sufficiently complete that the case can be reconstructed readily.

The gynecologic history should include the following information:

Chief complaint

Primary problem

Duration

Severity

Precipitating and ameliorating factors

Occurrence in relation to other events (e.g., menstrual cycle, coital activity, gastrointestinal activity, voiding, other pertinent functions)

History of similar symptom

Outcome of previous therapies

Impact on the patient’s quality of life, self-image, relationship with family, and daily activities

Role of other stresses in the chief complaint

Menstrual history

Age at menarche

Date of onset of last normal menstrual period

Timing of menstrual periods

Duration and quantity (i.e., number of pads used per day) of flow

Degree of discomfort

Premenstrual symptoms

Contraception (i.e., current and past methods)

Obstetric history

Number of pregnancies

Number of living children

Number of abortions, spontaneous or induced

History of previous pregnancies (i.e., duration of pregnancy, antepartum complications, duration of labor, type of delivery, anesthesia used, intrapartum complications, postpartum complications, hospital, physician)

Perinatal status of fetuses (i.e., birth weights, early growth and development of children, including feeding habits, growth, overall well-being, current status)

History of infertility (evaluation, diagnosis, treatment, outcome)

Medical historys

Allergies

Medications currently used

Past and current medical problems

Hospitalizations (reason, date, outcome)

Vaccinations (type, date), including HPV vaccine

Surgical history

Operative procedures (i.e., outcome, complications)

Review of systems

Pulmonary

Cardiovascular

Gastrointestinal

Urinary

Vascular

Neurologic

Endocrinologic

Immunologic

Breast symptoms

Masses

Galactorrhea

Pain

Family history

Social history

Exercise

Dietary habits (including calcium or folic acid supplementation)

Drug use

Alcohol use

Smoking habits

Marital status

Number of years married

Sexual history (partners, contraception, protection from STDs)

Occupational history (i.e., exposure to environmental toxins, ionizing radiation, infectious agents)

Emotional, physical, or sexual abuse

Family history

Significant medical and surgical disorders in family members

Chief Complaint

It often is effective to begin the history with an open-ended question concerning the symptoms that patients may have. This gives them the opportunity to describe their symptoms and concerns in their own words. Less information will be obtained if the interviewer asks only focused, closed-ended questions to which patients can answer only yes or no. Some clinicians find it helpful to have an outline of questions about the gynecologic history to obtain all the necessary information.

The following questions are typical of a gynecologic history:

What were the circumstances at the time the problem began (i.e., time, place, activity, cycles)?

What has been the sequence of events? (Having a calendar to refer to is often helpful.)

Have you had this problem before? Can you describe the previous occurrence and what led to its disappearance?

To what extent is the problem interfering with your daily life and the life of your family?

Have you had previous evaluations or treatments? (Records from previous physicians may be helpful.)

Why did you seek evaluation for the problem now?

What questions do you want answered today? What do you expect and want from today’s visit?

Menstrual History

The cycle interval is counted from the first day of menstrual flow of one cycle to the first day of next menstrual flow. There is a wide range of normal, and a recent change in the usual pattern may be a more reliable sign of a problem than the absolute interval. Although 28-day cycles are the median, only a small percentage of women have cycles of that length. The normal range for ovulatory cycles is between 24 and 35 days.

Duration of flow is usually 4 to 6 days. Estimating the amount of menstrual flow by history is difficult. The average blood loss is 30 mL (range 10 to 80 mL). The need to frequently change saturated tampons or pads (i.e., more often than one per hour for 6 or more hours) and the passage of many or large blood clots usually are signs of excessive blood flow.

Some degree of dysmenorrhea is common. It usually begins just before or soon after the onset of bleeding and subsides by day 2 or 3 of flow. The discomfort is characteristically lower midline and often is associated with backache and, in primary dysmenorrhea, with systemic symptoms such as lightheadedness, diarrhea, nausea, and headache. Mittelschmerz, or midcycle unilateral pelvic pain at the time of ovulation, usually is mild and seldom lasts for more than 1 or 2 days. It is important to ask whether or not there is bleeding between menstrual periods and whether this occurs after coitus. Intermenstrual bleeding is a characteristic sign of cervical cancer, although it also is present with benign lesions such as cervical polyps and fibroids or infection.

Finally, physicians should inquire about the presence of premenstrual syndrome (PMS). The symptoms experienced by women with PMS may be physical, emotional, and behavioral. The most common of the physical symptoms are fatigue, headache, abdominal bloating, breast tenderness and swelling, acne, joint pain, constipation, and recurring herpetic or yeast infections. Although these physical symptoms often are uncomfortable, most women with moderate to severe PMS complain most about their premenstrual emotional symptoms, especially depression, anxiety, hostility, irritability, rapid mood changes, altered libido, and sensitivity to rejection. Women with PMS also may experience changes in behavior, including physical or verbal abuse of others, suicide attempts, withdrawal, craving for or intolerance of alcohol, craving for sugar or chocolate, and binge eating. Many women report that long-standing or severe PMS causes psychologic or social problems that may be as disruptive as the premenstrual symptoms themselves.

Sexual History

The screening for sexual history is designed to determine whether major sexual problems exist that need in-depth evaluation and therapy and whether the patient should be referred elsewhere for more intensive evaluation. In an attempt to put patients at ease, physicians can begin the sexual history by prefacing questions with statements such as “Most people experience….” or “Because sexual problems can develop as part of other gynecologic problems….” If physicians can convey a willingness to help, patients are more likely to discuss problems. In addition, the screening history should begin with a discussion of topics that are unlikely to provoke anxiety. For example, questions about the occurrence of pain during intercourse are less likely to cause anxiety than questions about orgasmic function or noncoital sexual practices.

With these principles in mind, physicians can begin with a general question, such as “Are you having any sexual problems?” If the response is non-committal, a more specific question, for example, “Are you satisfied with the frequency of sexual relations?” can be posed. If a problem is identified,

physicians can proceed to the problem-oriented sexual history and ask about the date of onset, severity, previous evaluation and treatment, the results of such treatment, conditions that diminish or exacerbate the problem, the patient’s response to the problem, and the effect of the problem on the patient’s relationship with her partner. To conclude the screening history, physicians should invite patients to discuss concerns that have not been covered by the screening history. Even if a patient denies having any problems, the screening history is of value because it demonstrates the physician’s willingness to discuss sexual problems.

physicians can proceed to the problem-oriented sexual history and ask about the date of onset, severity, previous evaluation and treatment, the results of such treatment, conditions that diminish or exacerbate the problem, the patient’s response to the problem, and the effect of the problem on the patient’s relationship with her partner. To conclude the screening history, physicians should invite patients to discuss concerns that have not been covered by the screening history. Even if a patient denies having any problems, the screening history is of value because it demonstrates the physician’s willingness to discuss sexual problems.

The problem-oriented history is designed to differentiate organic from psychogenic sexual problems, determine the complexity of the problem, determine the need for referral of the patient to a more sophisticated sexual counselor, and provide information for the formulation of a treatment program if the physician elects to treat the patient. The problem-oriented sexual history should include onset, severity, course, conditions increasing the severity of the problem, prior evaluation and treatment if any, and the impact on the patient and her sexual or marital relationship. A treatment or referral can be formulated on the basis of discussion of these and related questions.

It is important to obtain a history of STDs. Physicians should tactfully question patients about past episodes of STDs, sexual practices, number of sexual partners, background of sexual partners, use of barrier forms of contraception, intravenous drug use, previous blood transfusions, genital lesions, persistent vaginal discharge, and pelvic pain. The discussion of STDs provides an opportunity to discuss modes of prevention, including the safe sex practice and the use of barrier methods of contraception when the sexual history of a partner is unknown.

Psychosocial History

Health care providers can play a vital role in identifying women who are victims of psychologic, physical, or sexual abuse. Unfortunately, women who are abused are often hesitant to acknowledge it. Questions should include the following:

Are you or have ever been in a relationship in which you have been physically hurt or threatened by a partner?

Have you ever been forced to have sex against your will?

Has your partner ever destroyed things that you care about?

Are you or have you ever been in a relationship in which you were treated badly?

If the answer to any of these questions is yes, the physical examination may reveal signs of physical abuse. In addition, many abused women may report chronic pain, sleep or appetite disorders, and frequent vaginal and urinary infections. One may suspect an abusive relationship if the patient’s partner is present at every office visit, insists on staying close to the patient, and answers questions directed to her. Once abuse is recognized, the physician must acknowledge the problem and direct the woman to an appropriate community resource. Inquiry about the woman’s safety should be made before she leaves the office. Some physicians obtain wallet-sized cards or brochures from local agencies that provide support and protection for battered women and place them in the restrooms. This provides an option for those women who would not acknowledge abuse when asked by their health care providers.

Depression is another very common condition that may be detected during an annual gynecologic examination. The potential life-threatening nature of depression and the availability of effective antidepressant medications with few side effects make it even more important to diagnose depression. To aid in diagnosing depression, physicians can ask the following questions:

Have you lost interest in the things you used to enjoy?

Do you feel sad, “blue,” or “down in the dumps”?

Do you have feelings of guilt or worthlessness?

Do you have thoughts of death or suicide?

Are you sleeping too much, or do you have difficulty falling or staying asleep?

Do you have a loss of energy and feel tired all the time?

An affirmative answer to one or more of these questions may indicate the patient is depressed and a candidate for psychotherapy or drug therapy. More than 50% of depressed individuals will respond to antidepressant therapy.

Adolescent History

As the percentage of adolescents increases, gynecologists find themselves dealing with problems unique to the 13- to 19-year-old age group. These include menstrual and breast disorders, pubertal development problems, and the challenges presented by sexually active adolescents. Over 50% of high school students, male and female, have had sexual intercourse, and less than half have reported that they used contraception the last time they had intercourse. The frequency of adolescent sexual activity and its consequences mean that gynecologists caring for adolescents certainly will encounter gynecologic problems such as STDs and pregnancy among their young patients. Gynecologists who provide such care to adolescents, particularly with respect to history taking, need to know their specific needs, with particular importance placed on confidentiality. The gynecologist must be prepared to handle multiple issues related to pubertal development, sexuality, self-esteem, and body image and approach the adolescent patient in a somewhat different manner than that used for adults. This includes having the parent present with young women, 14 years of age or less, during history taking and speaking to the adolescent first when she is fully clothed. If the adolescent refuses to have the parent or mother present, the physician may ask the young woman’s permission to speak to her mother or guardian with respect to important issues,

especially those requiring treatment. A detailed educational pamphlet on the first gynecologic visit is available at the ACOG website.

especially those requiring treatment. A detailed educational pamphlet on the first gynecologic visit is available at the ACOG website.

Gynecologic Examination

The pelvic examination is one of the most commonly performed medical procedures and is considered a highly unpleasant experience by most women. Aspects of the pelvic examination, such as genital exposure, make it likely that women will have feelings of anxiety, vulnerability, apprehension, or fear. It is important that the gynecologist observes a woman’s behavior, which will communicate her feelings and possibly anxieties. A complete physical examination most commonly is performed at the first visit. In order to reduce anxiety, patients should be encouraged to give feedback to the physician during the examination, especially when the examination causes pain. Description of the examination, including which portions may include mild to moderate discomfort (such as the rectal examination), should be given to the patient beforehand. When the physician enters the room, the patient should be sitting up on the examination table with the examination gown completely covering her. During the physical examination, a female chaperone, either a nurse or medical assistant, must be present. This woman can assist the physician and also lend psychologic support to the patient. The patient should be asked to lie down and place her feet in the stirrups, and the physician should be at the level of the patient’s head, speaking to her when her position is changed. This dialog may include the physician asking the patient about her symptoms, location of any pain, or other pertinent questions. Studies evaluating anxiety in women with respect to pelvic examinations have found those who have had a less positive first experience have higher anxiety levels with their gynecologists.

A general impression should be recorded of patient’s nutritional state, distribution and proportion of body fat, texture and condition of skin and hair, presence of facial or excessive body hair, acne, abnormal nevi (>5 mm, asymmetric outline, variable pigmentation, and indistinct borders), and any specific physical features. The patient’s hair is examined for cleanliness, texture, and scalp health. The eye examination may include ophthalmoscopy to detect retinal aberrations. The patient’s nose, throat, and teeth also can be checked. Finally, the anterior cervical, posterior cervical, and supraclavicular nodes, as well as the thyroid gland, should be palpated.

Hypertension is the most common chronic disease in women over 50 years of age. Therefore, every woman, especially one over 50, should have her blood pressure measured with her annual gynecologic examination. Careful cardiac auscultation may be performed as part of the gynecologic examination. Mitral valve prolapse (MVP), the most common cardiac condition diagnosed by auscultation in asymptomatic women, can be problematic during surgery or pregnancy. From the back, a curvature of the vertebral column can be assessed by observation and palpation.

Examination of the Breasts

The breast examination begins with a breast-oriented history. Patients are asked whether they have noted any lumps, pain, discharge, or other changes in their breasts. They also should be asked about breast surgery, date and results of the last mammogram, current and past hormone use, and family history of breast cancer. The axillary and supraclavicular nodes are then palpated. The breasts should be examined with patients both sitting or standing and lying supine. In the vertical position, the nipples and inframammary folds are evaluated for asymmetry. The examiner looks for elevation of one nipple, flattening of one breast, dimpling of the skin, or asymmetry by having patients raise both arms above the head and lean forward and then contract the pectoral muscles with hands on hips. Then, with patients in the supine position with one arm above the head, all quadrants of each breast are felt with the flat part of the distal phalanges of the fingers. The subareolar area also should be palpated, because up to 15% of carcinomas occur under the areola. The axillary and supraclavicular areas should be palpated for enlarged or tender lymph nodes. The nipples and adjacent areolar tissue are then compressed in an effort to express fluid from the nipple. The examination of the breasts should conclude with a description of the examination results and a recommendation for follow-up physical or imaging examinations.

Gynecologists as primary care physicians have the responsibility for screening mammography. A diagnostic approach to the breast, including clinical breast examination, possible fine-needle aspiration, and mammography, may be implemented by the gynecologist and performed with findings of a breast mass or suspicious area. Ongoing discussion has addressed the value of screening mammography with respect to breast cancer mortality. Studies have noted that mammograms can be lifesaving and that recommendations for gynecologists based on all available information are to urge all women to follow the advice of their physicians and obtain mammograms per current clinical guidelines.

Examination of the Abdomen

Patients should be positioned supine, with arms against the body to relax the abdominal musculature. If necessary to obtain adequate relaxation, the knees can be elevated and flexed. In a methodical and consistent manner, all quadrants of the abdomen should be palpated. Relaxation of the abdomen to evaluate a suspected mass can be assisted by having patients breathe deeply and then exhale. After all quadrants have been examined, the inguinal nodes should be palpated. Asking about the origin of abdominal scars

may provide information that was not elicited during the history.

may provide information that was not elicited during the history.

Bulging of the flanks suggests free abdominal fluid, but thin-walled ovarian cysts and irregularly shaped uterine leiomyomata may have a similar clinical picture. Although large ovarian cysts and leiomyomata most commonly cause protrusion of the anterior abdominal wall, there are many confusing exceptions. Percussion for areas of flatness or tympany and for shifting dullness may aid in determining whether the distension is caused by intraperitoneal fluid or by intestinal gas. Auscultation is useful in differentiating among a large tumor and distended bowel.

Examination of the Extremities

Examination of the lower extremities supplies important information regarding the cardiovascular system. Any edema or varicosities should be noted. In a patient with congenital absence of the vagina, evidence of muscle atrophy in the extremities should be sought because such patients may have nerve root compression secondary to congenital vertebral anomalies. The peripheral pulses and reflexes also may be evaluated at this time. Examination of the calves and ankles for melanomas or dysplastic nevi is advisable.

Pelvic Examination

The first examination of the female genitourinary system often takes place in the neonatal period. An examination is indicated at any age when abnormal bleeding or pelvic symptoms are present, there are questions about primary or secondary sexual development, or sexual activity is being initiated. For teenagers, the first pelvic examination should probably occur at 18 years of age or at the initiation of sexual activity, whichever comes first. Examinations usually are repeated at yearly intervals, at which time a Pap smear should be performed in addition to a pelvic examination and a screening for breast cancer and hypertension in the later reproductive years.

The pelvic examination provides physicians with an opportunity to answer questions and to educate with respect to pelvic anatomy, physical development, and sexual function. Patients often are reassured if the physician carries on a running dialogue, describing the findings, asking and answering questions, and demonstrating on occasion the physical findings with the aid of a handheld mirror. To maximize the educational aspects of an examination, clinicians can (a) describe all procedures in advance; (b) maintain eye contact with patients during the examination, whenever possible; and (c) explain all findings clearly.

The pelvic examination is performed with the patient lying on her back with both knees flexed. The buttocks are positioned at the edge of the examining table, and the feet are supported by stirrups. This position allows the necessary exposure of the pelvic organs. Traditionally, patients have been placed with the head and body in a horizontal position. This position does not allow maintaining eye contact and increases a patient’s sense of vulnerability. The alternative, assuming the availability of an adjustable examination table, is to elevate the head of the table at an angle between 30 and 90 degrees. There are no apparent technical disadvantages to this alternative position, and many patients find it easier to relax, actually making the bimanual part of the examination more accurate. The patient should empty her bladder just before the examination.

The minimal equipment needed to perform a pelvic examination includes a good light source, a speculum of the correct size, a nonsterile glove, and a water-soluble lubricant. Additional supplies that should be available in the examination room include a variety of speculum sizes, materials to obtain cytologic samples including fixatives, various culture media, large cotton-tipped swabs, pH indicator paper, and screening tests for fecal occult blood. Specialized examinations require other specific equipment.

The pelvic examination begins with inspection of the vulva. Physicians should note and record evidence of developmental abnormalities as well as the general state of cleanliness, discharge, hair growth and distribution, and abnormalities of the skin, including tumors, ulcerations, scratch marks, rashes, and minor lacerations or bruises. Vulvar varicosities or hemorrhoids also should be noted. A careful inspection of the skin folds, vulva, and pubic hair may reveal occult lesions or infection. The vulva should be palpated for subcutaneous lesions. The labia are then spread, and the condition of the hymen and vulvovaginal skin and the size of the clitoris are noted. The examination should be performed in a systematic manner and include the labia majora, labia minora, vestibule, urethral opening, periurethral glands, Bartholin glands, perineum, anus, and perianal areas. With an index finger in the outer vagina and the thumb on the perineum, the labia and urethra are palpated for masses or tenderness. Patients are asked to contract the muscles of the vaginal opening to assess the tone of the levator muscles and the degree of perineal support and then to strain to reveal the presence of a urethrocele, cystocele, rectocele, enterocele, or vaginal or cervical prolapse.

The vagina should first be inspected with the aid of a speculum. Specula come in various sizes, and an appropriate size should be selected, using the largest size that is comfortable and provides the best visualization. Painless insertion of the speculum may be aided by several techniques. First, the muscles at the opening of the vagina may be relaxed by gentle downward pressure with one or two fingers. The speculum may be moistened with warm water before insertion, but other types of lubricants should be avoided if cultures or cytologic samples are to be collected. The speculum blades should be inserted obliquely, not vertically, through the introitus; immediately rotated to the horizontal plane; and then slowly opened after the vaginal apex is reached. The vaginal walls and cervix should

be inspected for lesions. Any vaginal discharge should be assessed for volume, color, consistency, and odor. The endocervical mucus also should be examined. Samples for cervical or vaginal cytologic examination and cultures and direct microscopic examination of the vaginal or cervical discharge should be obtained as indicated. Before the speculum is removed, the cervix should be evaluated for ectropion, erosion, infection, discharge, lacerations, polyps, ulcerations, and tumors. As the speculum is removed, with the patient bearing down, the degree of vaginal wall relaxation and uterine prolapse can be assessed. With the speculum removed and the patient still bearing down, they physician can screen for stress incontinence.

be inspected for lesions. Any vaginal discharge should be assessed for volume, color, consistency, and odor. The endocervical mucus also should be examined. Samples for cervical or vaginal cytologic examination and cultures and direct microscopic examination of the vaginal or cervical discharge should be obtained as indicated. Before the speculum is removed, the cervix should be evaluated for ectropion, erosion, infection, discharge, lacerations, polyps, ulcerations, and tumors. As the speculum is removed, with the patient bearing down, the degree of vaginal wall relaxation and uterine prolapse can be assessed. With the speculum removed and the patient still bearing down, they physician can screen for stress incontinence.

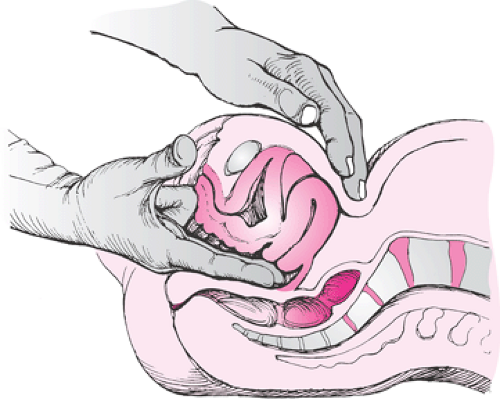

The technique for the bimanual examination is shown in Figures 29.1,29.2,29.3,29.4,29.5. After the speculum has been withdrawn, the physician should gently insert the index and middle fingers along the posterior wall of the vagina. At the same time, the other hand is placed on the patient’s abdomen in the midline. The first palpable structure is the cervix. Next is the uterine fundus. The bimanual technique can outline its position, size, shape, consistency, and degree of mobility. Uterine or cervical mobility can be assessed further by placing the fingers on one side of the uterus and moving them to the contralateral side. This can be done on both the right and left sides to detect chronic or acute inflammatory changes and fixation. The other hand is then placed on one lower quadrant of the abdomen and slowly moved inferiorly and medially to meet the fingers of the hand examining the vagina. In this way, adnexal structures on that side can be appreciated. The degree of adherence of an adnexal structure to the uterus often can be ascertained. Enlargement, consistency, and position of ovaries and tubes can be noted. The ovary is a sensitive structure, and patients differ in tolerance to palpation. The contralateral side should be examined similarly. Finally, the vaginal walls and adjacent structures (bladder and rectum) are palpated. The glove of the hand used for vaginal examination is then replaced with a clean glove for the rectovaginal or rectal examination.

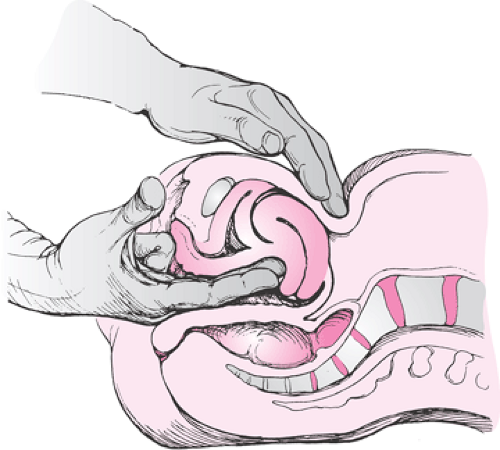

The rectal examination is uncomfortable, but it can be made less so if the physician gently places a finger into the anal opening, requests that the patient valsalva and wait for the anal sphincter to relax before proceeding. The middle finger is inserted into the rectum and the index finger into the vagina. The tone and symmetry of the sphincter are determined. The parametrial tissue is then palpated between the index finger in the vagina and the middle finger in the rectum. Finally, the posterior uterine surface, adnexal areas, uterosacral ligaments, and pouch of Douglas, along with the ano-rectal area, are palpated. The rectovaginal examination enhances the evaluation of cul-de-sac or ovarian pathology. Particles of hard fecal material may interfere with an accurate examination.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree