Office Evaluation of the Child and Adolescent

S. Jean Emans

Office Evaluation of the Child and Adolescent

Gynecologic assessment and inspection of the external genitalia of the infant and child are an opportunity to provide preventive health care and to diagnose important clinical conditions. Although gynecologic problems are uncommon in young girls, assessment of breast development and the external genitalia should be part of the routine physical examination. When the child presents for an evaluation for a specific problem, there should be a “problem-focused” history and physical exam. These visits can also be utilized as opportunities to teach anatomy and to discuss development and home care. The presence of clitoromegaly, a hernia, early signs of puberty, Candida vulvitis, vulvar dermatoses, or an abnormality in the configuration of the hymen may be a clue to other problems.

A healthy dialogue between parents and children on issues of sexuality should begin during the prepubertal years. Parents should be encouraged to answer the questions of their young children with simple facts and correct anatomic terminology.

Obtaining the History

Vaginal discharge or bleeding, pruritus, signs of sexual development, or an allegation of sexual abuse should prompt a thorough evaluation. The nature of the history depends on the presenting complaint. If the problem is vaginitis, questions should focus on the timing of the onset of symptoms; the type of discharge; perineal hygiene; skin conditions (e.g., eczema, psoriasis); antibiotic therapy; recent infections in the patient or other members of the family, including streptococcal infection and pinworm infestation; masturbation; and the possibility of sexual abuse (see Chapter 30). Behavioral changes and somatic symptoms such as abdominal pain, headaches, and enuresis may suggest the possibility of abuse. Information on the caretakers should always be elicited. If the problem is vaginal bleeding, the history should include information about recent growth and development, signs of puberty, the use of hormone creams or tablets, trauma, vaginal discharge, and any previous finding of foreign bodies in the vagina or other orifices. Although the history is usually obtained chiefly from a parent, the child should first be asked questions about toys or school to put her at ease. Then, questions may be asked about genital complaints, genital contact, and, depending on the complaint, whether she has ever placed something in her vagina. Eye contact with the child should be maintained, and she should be told that she is an important part of the team. Questions focusing on what has bothered the child, such as itching or discharge, can help her understand why the examination is important. She should be given the opportunity to ask her own questions. A questionnaire can be used to speed the intake process so that the young child does not become fidgety while the history is being taken. However, the history-taking time can be used advantageously to put the child at ease.

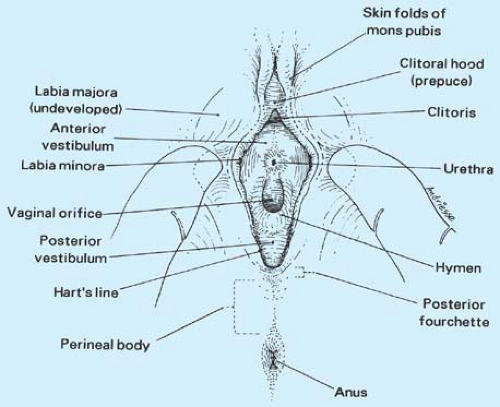

Gynecologic Examination

The gynecologic examination should be carefully explained in advance to the child and parents/guardians. It is extremely important to tell the parent that the size of the vaginal opening is quite variable and that the examination will be painless and in no way alter the hymen. A diagram showing the vulva is often helpful, as many parents still believe inaccurately that the virginal introitus is totally covered by the hymen (Fig. 1-1). Gynecologic assessment of the child typically involves inspection of the genitalia, not instrumentation of the vagina.

Both parent and child should be told that the instruments to be used are specially designed for little girls and do not enter the vagina. The otoscope or hand lens to be used for external examination should be shown to the child with an assurance that the clinician will use these instruments “to look.” The child may wish to look through the lens of the otoscope. If a colposcope will be used for an evaluation of sexual abuse, the child should have a chance to look at the instrument, turn the light on and off, and view fingers or jewelry through the binocular eyepieces so that she will feel more comfortable with the examination.

The child can then be offered her choice of gown color and asked whether she wishes to have her parent lift her onto the table or climb “up the big stairs.” In our clinic, the parent typically stays in the room to talk with the young child and assist in the examination. Although the father, mother, both parents, or a relative may accompany the child for the assessment, most commonly the mother plays an active role during the examination. The older child should be asked whom she prefers to have in or out of the room during the examination. Most children and many young adolescents prefer their mothers in the room; most middle to late adolescents prefer that their mothers not be present in the examination room.

The majority of children are comfortable on the examining tables with the mother (or father or other caretaker) sitting close by or holding a hand. Some girls are quite fearful, especially if they have previously been sexually abused or had a prior painful genital examination. In this case, the mother or other caretaker can sit on the table with the child or even with her feet in stirrups and have the child’s legs straddle her thighs in a (semi) reclined position (Figs. 1-2 to 1-5). A hand mirror can help the child relax and allows her to become an active participant in the examination. The mirror can be used for both education and distraction. If the clinician is confident and relaxed, the patient usually responds with cooperation. An abrupt or hurried approach will precipitate anxiety and resistance in the child. Sometimes it is necessary to leave the room and return when the patient feels ready. Occasionally, a very anxious or fearful child needs to return several days later to have the examination completed. The tempo of the examination depends on the urgency of evaluating a problem and the degree of cooperation that

can be elicited. For example, if a child has had a discharge for months, the examination can extend over several visits, if necessary, so that the clinician can gain the confidence of the child. If a child has significant vaginal bleeding or has experienced trauma, or if cooperation cannot be elicited and a view of the vagina is needed, then an examination with sedation or under anesthesia may be necessary.

can be elicited. For example, if a child has had a discharge for months, the examination can extend over several visits, if necessary, so that the clinician can gain the confidence of the child. If a child has significant vaginal bleeding or has experienced trauma, or if cooperation cannot be elicited and a view of the vagina is needed, then an examination with sedation or under anesthesia may be necessary.

The examination of any child with gynecologic complaints should include a general pediatric assessment including the child’s weight and height (calculation of body mass index [BMI]), skin, head and neck, chest wall, heart, lungs, and abdomen. The breasts should be carefully inspected and palpated. The increasing diameter of the areola or a unilateral tender breast bud is often the first sign of puberty. The abdominal examination is often easier if the child places her hands on the examiner’s hand; she is then less likely to tense her muscles or complain of being “tickled.” The inguinal areas should be carefully palpated for a hernia or gonad; occasionally, an inguinal gonad is the testis of an undiagnosed child with 46,XY disorder of sexual development (46,XY DSD, formerly termed male pseudohermaphrodite; see Chapter 3). The skin should be examined for evidence of other skin conditions such as eczema, psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, hemangioma, or café au lait spots.

Although the complete gynecologic examination of the child includes inspection of the external genitalia, visualization of the vagina and cervix, and rectoabdominal palpation, the extent of the examination should be tailored to the presenting complaint. Examination of the child is usually possible without sedation or anesthesia if the child has not been traumatized by previous examinations and if the clinician proceeds slowly. The child should be explicitly told that the examination will not hurt. For

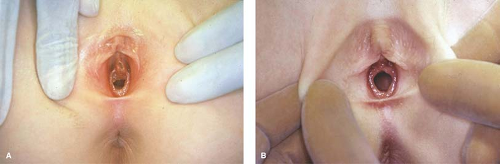

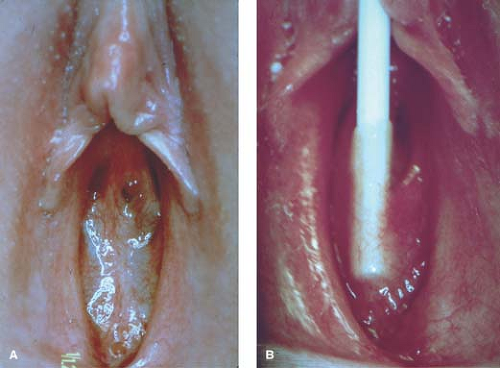

the initial examination, the young child should be in a supine position with her knees apart and feet touching in the frog-leg position or in the lithotomy position with the use of adjustable stirrups, with or without a caretaker assisting (Figs. 1-2 to 1-5). Asking a child whether she has ever seen a frog and whether she can say “ribbit” will often put her at ease so that she can assume the correct position “like a frog.” Other young girls like to refer to this position as “making your legs like a butterfly’s wings.” A colorful poster on the ceiling or wall is a good distraction. During inspection of the external genitalia, the young girl may be less anxious if she assists the clinician by holding the labia apart. Occasionally, a child does not wish to remove her panties. The examination can still be accomplished in many girls by gently moving the crotch of the underwear to one side to allow inspection. The clinician should note the presence of pubic hair, the size of the clitoris, the configuration of the hymen, signs of estrogenization of the vagina and hymen, and perineal hygiene. The normal clitoral glans in the premenarcheal child is on average 3 mm in length and 3 mm in transverse diameter (1). The normal external genital structures are usually easily visible with gentle traction downward and laterally (Fig. 1-6A). The hymen will often gape open if the child is asked to cough or take a deep breath. If the hymenal orifice and edges of the hymen are not visible, the labia can be gently gripped and pulled forward in a traction maneuver to enable viewing of the anterior vagina (Fig. 1-6B). The vaginal mucosa of the prepubertal girl appears thin and red in contrast with the moist, dull pink, estrogenized mucosa of the pubertal girl. Frequently, the perihymenal tissue is erythematous. Friability of the posterior fourchette as the labia are separated can occur in children with vulvitis or irritation from sexual abuse or if the labia are separated widely and the tissue tears (2).

the initial examination, the young child should be in a supine position with her knees apart and feet touching in the frog-leg position or in the lithotomy position with the use of adjustable stirrups, with or without a caretaker assisting (Figs. 1-2 to 1-5). Asking a child whether she has ever seen a frog and whether she can say “ribbit” will often put her at ease so that she can assume the correct position “like a frog.” Other young girls like to refer to this position as “making your legs like a butterfly’s wings.” A colorful poster on the ceiling or wall is a good distraction. During inspection of the external genitalia, the young girl may be less anxious if she assists the clinician by holding the labia apart. Occasionally, a child does not wish to remove her panties. The examination can still be accomplished in many girls by gently moving the crotch of the underwear to one side to allow inspection. The clinician should note the presence of pubic hair, the size of the clitoris, the configuration of the hymen, signs of estrogenization of the vagina and hymen, and perineal hygiene. The normal clitoral glans in the premenarcheal child is on average 3 mm in length and 3 mm in transverse diameter (1). The normal external genital structures are usually easily visible with gentle traction downward and laterally (Fig. 1-6A). The hymen will often gape open if the child is asked to cough or take a deep breath. If the hymenal orifice and edges of the hymen are not visible, the labia can be gently gripped and pulled forward in a traction maneuver to enable viewing of the anterior vagina (Fig. 1-6B). The vaginal mucosa of the prepubertal girl appears thin and red in contrast with the moist, dull pink, estrogenized mucosa of the pubertal girl. Frequently, the perihymenal tissue is erythematous. Friability of the posterior fourchette as the labia are separated can occur in children with vulvitis or irritation from sexual abuse or if the labia are separated widely and the tissue tears (2).

Figure 1-6. Examination of the vulva, hymen, and anterior vagina by (A) gentle lateral retraction and (B) gentle gripping of the labia and pulling anteriorly. |

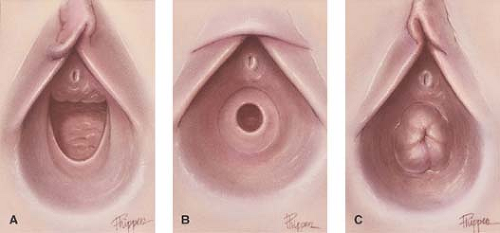

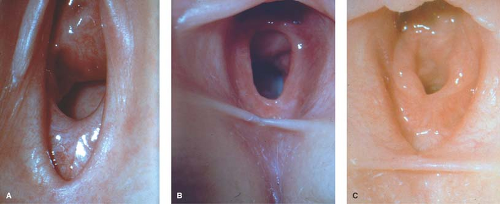

The configuration of the hymen should be noted and accurately described (Figs. 1-7 and 1-8). A hand lens or the light and magnification of an otoscope, without a speculum, can be used (Fig. 1-9). Hymens can be classified as posterior rim (or crescent), annular, or redundant (3). In girls with a redundant hymen, the edges of the hymen and the anterior vagina are often difficult to visualize. Congenital abnormalities of the hymen, especially microperforate and septate hymens, are

not uncommon (Figs. 1-10 to 1-17; see also Chapter 12 and www.youngwomenshealth.org/hymen.html). It may initially be difficult to establish the presence of an opening in a microperforate hymen. Several techniques are useful: a small amount of warm water or saline can be squirted with a syringe or an Angiocath, or the young girl can be placed in the knee–chest position (Fig. 1-18). Probing can also be done with a small urethral catheter or feeding tube (see Fig. 1-16), or a nasopharyngeal Calgiswab moistened with saline. If there is a small slit-like opening inferior to the urethra, then the small swab needs to be inserted in a fashion parallel to the hymenal tissue. Applying a small amount of lidocaine jelly may reduce discomfort if probing is necessary and if vaginal cultures are not needed as part of the evaluation. Congenital absence of the hymen has not been documented (4,5).

not uncommon (Figs. 1-10 to 1-17; see also Chapter 12 and www.youngwomenshealth.org/hymen.html). It may initially be difficult to establish the presence of an opening in a microperforate hymen. Several techniques are useful: a small amount of warm water or saline can be squirted with a syringe or an Angiocath, or the young girl can be placed in the knee–chest position (Fig. 1-18). Probing can also be done with a small urethral catheter or feeding tube (see Fig. 1-16), or a nasopharyngeal Calgiswab moistened with saline. If there is a small slit-like opening inferior to the urethra, then the small swab needs to be inserted in a fashion parallel to the hymenal tissue. Applying a small amount of lidocaine jelly may reduce discomfort if probing is necessary and if vaginal cultures are not needed as part of the evaluation. Congenital absence of the hymen has not been documented (4,5).

Acquired abnormalities of the hymen usually result from sexual abuse and rarely from accidental trauma (see Chapter 4; Chapter 16; and Chapter 30, Figs. 30-1 to 30-5). Chapter 16 addresses issues of trauma; Chapter 30 reviews the most current literature on normal and abnormal anogenital findings and the signs associated with sexual abuse. Signs of acute trauma from sexual abuse include hematomas, abrasions, lacerations, hymenal transections, and vulvar erythema and irritation. Signs of previous sexual abuse may include acute and healed trauma, hymenal remnants, scars, and hymenal transections, which may heal in a V shape or a U shape. It should be remembered that in most girls with a history of substantiated sexual abuse, the findings on genital examination are normal.

Figure 1-8. Types of hymens (photographed through a colposcope): (A) crescentic hymen, (B) annular hymen, and (C) redundant hymen with crescent appearance after retraction. |

The diameter of the hymenal orifice is variable in children and the transverse and anterior–posterior measurements are influenced by age, relaxation of the child, method of examination and measurement, and type of hymen. The older the child and the more relaxed she is, the larger the opening. The opening is larger with retraction on the labia and when the child is in the knee–chest position than with gentle separation alone when the supine position is used. The orifice of a posterior rim hymen appears larger than the opening of a redundant hymen. Our study of 3- to 6-year-old girls found a mean

transverse measurement of 2.9 ± 1.3 mm (range 1 to 6 mm) and mean anterior–posterior measurement of 3.3 ± 1.5 mm (range 1 to 7 mm) (2) (see Chapter 30 for other studies). Although a child with a history of sexual abuse may have a large hymenal orifice, it is the absence of hymenal tissue that is the significant finding. Thus, measurements are not recommended as part of the gynecologic evaluation.

transverse measurement of 2.9 ± 1.3 mm (range 1 to 6 mm) and mean anterior–posterior measurement of 3.3 ± 1.5 mm (range 1 to 7 mm) (2) (see Chapter 30 for other studies). Although a child with a history of sexual abuse may have a large hymenal orifice, it is the absence of hymenal tissue that is the significant finding. Thus, measurements are not recommended as part of the gynecologic evaluation.

The anus and labia should always be examined for cleanliness, excoriations, and erythema. Perianal excoriation may be a clue to pinworm infestation. Normal findings, as well as those associated with sexual abuse, are noted in Chapter 30.

For girls with vulvitis or lichen sclerosus, an external examination may be all that is needed to make a diagnosis and formulate a treatment plan (see Chapters 4 and 5). However, if there is discharge, bleeding, or any other complaint that may be of vaginal origin, the clinician should proceed with visualization of the vagina.

Figure 1-10. Types of hymens: (A) normal, (B) imperforate, (C) microperforate, (D) cribriform, and (E) septate. |

In girls older than 2 years, the knee–chest position provides a particularly good view of the vagina and cervix without instrumentation (6). The patient is told that she should lie with her chest on the table and her “bottom in the air.” She is reassured that the examiner plans to “take a look at her bottom” but will not put anything inside her. In the knee–chest position, the child rests her head to one side on her folded arms and supports her weight on bent knees (6 to 8 in. apart). With her buttocks held up in the air, she is encouraged to let her spine and stomach “sag downward.” Some girls like to hear that they may have slept in this position when they were “little.” A pillow can be placed under the girl’s abdomen if she desires. A sheet can also be used so that she feels covered. An assistant or the mother helps hold the buttocks apart, pressing laterally and slightly upward. As the child takes deep breaths, the vaginal orifice falls open for examination (see Fig. 1-18). In 80% to 90% of prepubertal

girls, an ordinary otoscope head, used without a speculum (see Fig. 1-9), provides the magnification and light necessary to enable visualization of the lower vagina and usually the upper vagina and cervix. The child’s anxiety will be allayed if she is again shown the otoscope light and efforts are made to gain her full confidence before this part of the examination. A running conversation about school, toys, and siblings often diverts the child’s attention and helps her maintain this position for several minutes without moving or objecting. Since the vagina of the prepubertal child is quite short, a foreign body or a lesion is often easily detected. Similarly, a supine position with the child’s legs flexed on her abdomen also enhances visualization of the hymen, vagina, and anus.

girls, an ordinary otoscope head, used without a speculum (see Fig. 1-9), provides the magnification and light necessary to enable visualization of the lower vagina and usually the upper vagina and cervix. The child’s anxiety will be allayed if she is again shown the otoscope light and efforts are made to gain her full confidence before this part of the examination. A running conversation about school, toys, and siblings often diverts the child’s attention and helps her maintain this position for several minutes without moving or objecting. Since the vagina of the prepubertal child is quite short, a foreign body or a lesion is often easily detected. Similarly, a supine position with the child’s legs flexed on her abdomen also enhances visualization of the hymen, vagina, and anus.

Vaginoscopy

If vaginal assessment cannot be accomplished in the office for the child with vaginal bleeding or persistent discharge, an examination with sedation or under anesthesia is the next step. An examination with sedation or under anesthesia may also be important if vulvar biopsy is needed for undiagnosed vulvar dystrophies or excision of a suspicious nevus or other vulvar lesion. A long Killian nasal speculum with a light source can be helpful for direct visualization of the vagina and cervix (Fig. 1-19). The use of a hysteroscope, cystoscope, or flexible narrow-diameter fiberoptic scope with liquid insufflation can be helpful for magnification and identification of vaginal or cervical lesions. As the vagina is filled with the liquid distention media, the labia are “pinched closed” so that the vagina will distend and facilitate evaluation.

Almost all vaginoscopy is done under sedation or anesthesia. Depending on the office setting, a few clinicians have been

able to perform vaginoscopy using local application of lidocaine to visualize the upper vagina and cervix in the cooperative older child. The child is examined in a supine position with her knees apart. A step-by-step method of inserting the vaginoscope in the young child was originally described by Capraro (7). The child is first allowed to touch the instrument and is told that it feels “slippery, funny, and cool.” The examiner then places the instrument against the child’s inner thigh, against her labia, and finally into the vagina, repeating the words with each step.

able to perform vaginoscopy using local application of lidocaine to visualize the upper vagina and cervix in the cooperative older child. The child is examined in a supine position with her knees apart. A step-by-step method of inserting the vaginoscope in the young child was originally described by Capraro (7). The child is first allowed to touch the instrument and is told that it feels “slippery, funny, and cool.” The examiner then places the instrument against the child’s inner thigh, against her labia, and finally into the vagina, repeating the words with each step.

Figure 1-16. Microperforate hymens. A: The opening difficult to visualize. B: The opening gently probed. |

Vaginal Samples

If a vaginal discharge is present in the prepubertal child, samples should be obtained for culture and, if additional swabs can be easily obtained, for saline and potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparations (see section on Wet Preparations, p. 17). Usually, the child prefers to lie on her back with her knees apart and with her feet together or in the stirrups so that she can watch the procedure without becoming excessively anxious. A nasopharyngeal Calgiswab moistened with nonbacteriostatic saline, a soft plastic eyedropper, or a small feeding tube or urethral catheter with a syringe (8) can be gently inserted through the hymenal opening to obtain secretions or to obtain a vaginal wash sample. The child should be allowed to feel a Calgiswab, cotton-tipped applicator, feeding tube, or catheter on her skin before a similar sterile device is inserted into her vagina. For example, a cotton-tipped applicator can be gently stroked over the back of her hand to allow her to feel it as “soft” or “ticklish.” For the prepubertal child, we usually use a nasopharyngeal Calgiswab moistened with nonbacteriostatic saline (such as ampules of nebulizer saline) for routine vaginal cultures (Fig. 1-20). If a small swab is used, care should be taken to place it into the vagina without touching the edges of the hymen. The child can be asked to cough as the examiner inserts the swab. This action distracts the child and makes the hymen gape open. The child will be amazed that no discomfort is felt. For the child who will not allow an intravaginal sampling, Muram has used a technique of squirting saline with an Angiocath (no needle) to fill the vagina followed by holding three swabs perpendicular just outside the vagina with the labia held closed over the swabs by the examiner. The child is asked to cough hard to expel the solution, and the wet swabs are used for the needed tests.

The Calgiswab is placed into a transport Culturette II with medium, and the bacteriology laboratory typically plates on the standard genitourinary media (blood agar, MacConkey, and chocolate media). If gonorrhea infection is possible, a test for Neisseria gonorrhoeae is done by sending a vaginal sample

obtained using a small male (urethral) swab or a urine sample for a nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) or by plating the swab obtained directly on modified Thayer–Martin–Jembec medium (preferred if evaluation of sexual abuse) at the time of the examination. The laboratory should be notified that the Thayer–Martin–Jembec medium being processed is from the vagina of a prepubertal child so that if a Neisseria species grows, it is identified as N. gonorrhoeae for medicolegal purposes. Bacterial isolates initially identified as N. gonorrhoeae from children may be other Neisseria species such as N. lactamica, N. meningitidis, and N. cinerea (9,10). Similar caution is important for NAATs; if the urine or vaginal sample is positive for gonorrhea on the NAAT, a second or confirmatory test is done. Similar caveats should be observed for Chlamydia testing. Although culture tests for Chlamydia trachomatis do not require confirmation, they are significantly less sensitive than NAATs. For most girls, a NAAT is obtained from a urine or vaginal sample; a positive test should be retained and confirmed with a second test that targets a different sequence (11). The association of N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis with sexual abuse necessitates sensitive and specific methods (see Chapters 4, 18, and 30). For patients who complain of itching or have suspected yeast infection, a Biggy agar culture can be incubated and read in the office or laboratory (see p. 18).

obtained using a small male (urethral) swab or a urine sample for a nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) or by plating the swab obtained directly on modified Thayer–Martin–Jembec medium (preferred if evaluation of sexual abuse) at the time of the examination. The laboratory should be notified that the Thayer–Martin–Jembec medium being processed is from the vagina of a prepubertal child so that if a Neisseria species grows, it is identified as N. gonorrhoeae for medicolegal purposes. Bacterial isolates initially identified as N. gonorrhoeae from children may be other Neisseria species such as N. lactamica, N. meningitidis, and N. cinerea (9,10). Similar caution is important for NAATs; if the urine or vaginal sample is positive for gonorrhea on the NAAT, a second or confirmatory test is done. Similar caveats should be observed for Chlamydia testing. Although culture tests for Chlamydia trachomatis do not require confirmation, they are significantly less sensitive than NAATs. For most girls, a NAAT is obtained from a urine or vaginal sample; a positive test should be retained and confirmed with a second test that targets a different sequence (11). The association of N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis with sexual abuse necessitates sensitive and specific methods (see Chapters 4, 18, and 30). For patients who complain of itching or have suspected yeast infection, a Biggy agar culture can be incubated and read in the office or laboratory (see p. 18).

Completing the Examination

After the vaginal samples have been obtained, a rectoabdominal examination may be indicated for the child with persistent discharge, bleeding, or pelvic/abdominal pain. Alternatively, the clinician may choose to obtain an ultrasound to assess for ovarian cysts, uterine size, or other abnormalities, but a small vaginal lesion or foreign body may not be apparent on ultrasound.

Figure 1-19. (A) Examination of patient under anesthesia, (B) using a Killian nasal speculum with fiberoptic light. (Obtained from Codman and Shurtleff, Inc., Pacella Drive, Randolph, MA). |

Figure 1-20. Calgiswab for obtaining vaginal specimens in the prepubertal girl (left). Transport tube (center) and Biggy agar (for Candida, if suspected) (right). |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree