Chapter 32

Neurologic Complications of Pregnancy and Neuraxial Anesthesia

Felicity Reynolds MD, MBBS, FRCA, FRCOG ad eundem

Chapter Outline

Neurologic complications of childbirth may be associated with neuraxial analgesia and anesthesia or may result from childbirth itself. Complications of neuraxial anesthesia may be immediate, such as motor blockade, unexpectedly high or prolonged blockade, and seizures after unintentional intravenous injection of local anesthetic, or they may be prolonged or delayed (sequelae). Immediate complications of neuraxial anesthesia are described in Chapter 23; here the discussion is focused on neurologic sequelae.

Although neurologic disorders after childbirth are more likely to have obstetric than anesthetic causes, neuraxial anesthesia is all too often blamed. For example, Tubridy and Redmond1 described seven women referred with neurologic symptoms after childbirth, all of which had been attributed to epidural analgesia. The women suffered from brachial neuritis, peroneal neuropathy, femoral neuropathy, neck strain, and leg symptoms for which there was no obvious physical cause. In such circumstances, a careful history and neurologic examination, together with diagnostic aids such as electromyography, nerve conduction studies, and imaging techniques, can localize the lesion and differentiate obstetric from anesthetic causes. For example, it should be possible to distinguish by simple clinical means between a mononeuropathy, which is likely to have an obstetric cause, and a radiculopathy resulting from neuraxial blockade. Accurate and prompt diagnosis is essential.

The Incidence of Neurologic Sequelae

Patients frequently ask obstetricians and anesthesia providers about the incidence of complications of neuraxial anesthesia, but even if accurate data were available, the question has no true answer. The incidence of neurologic complications varies widely according to local practice and the skill and training of the practitioners. Some old surveys are based on accurate local records, but the data relate to a time when obstetric and anesthetic practices, equipment, and drugs were less safe than they are today. The incidence of serious complications is now too low to be estimated accurately on a local basis. Nonetheless, anesthesia providers have a duty to inform patients of the complications associated with a proposed procedure and are expected to give some figure for the level of risk, however meaningless such an estimate may be.

Obstetric Surveys

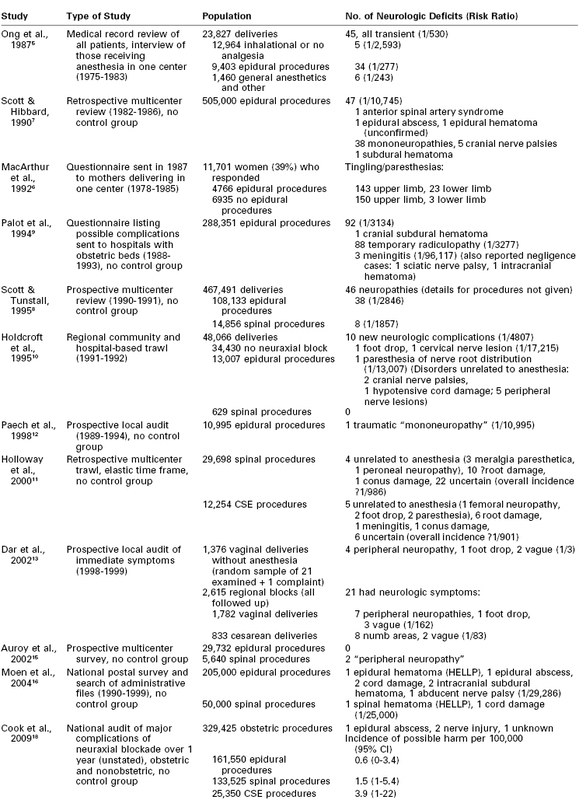

In early surveys, the reported incidence of neurologic deficits in obstetric patients ranged from 1 in 2100 to 1 in 6400.2,3 During this period, long labor and difficult rotational forceps delivery were commonplace and neuraxial anesthesia was relatively unusual. Many surveys have subsequently attempted to assess the incidence of neurologic complications of neuraxial anesthesia, overlooking obstetric problems and other sources of error (Box 32-1).

Some of the more relevant surveys are listed in Table 32-1, those of the 20th century having been ably reviewed by Loo et al.4 in 2000. Ong et al.5 reviewed the medical records of all women who delivered in Winnipeg over a 9-year period and interviewed all those who received anesthesia care. All neurologic deficits in this series were transient, with none lasting more than 72 hours. The incidence of neurologic symptoms was similar after epidural and general anesthesia, but symptoms were more likely to be reported by women who received anesthesia than by those who received none. This is not surprising because only women who received anesthesia were interviewed. Indeed, the survey identified 45 cases of neurologic deficit, but only 10 had been noted in the hospital record, suggesting that many deficits may have been missed in the patients who were not interviewed. Moreover, modern statistical methods such as logistic regression analysis were not used to tease out the influence of prolonged labor and traumatic delivery, which the investigators noted as possible causative factors.

In a large retrospective survey of long-term symptoms, women who delivered in one hospital in Birmingham, United Kingdom, were asked to recall events 2 to 9 years after delivery.6 The response rate was only 39%, and all those (and only those) who received epidural analgesia had been interviewed intensively about their symptoms immediately postpartum, thereby enhancing subsequent recall in this subset of the population. Logistic regression analysis demonstrated a link between epidural analgesia and many symptoms, including tingling and numbness in the arms, calling into question any causative link with neuraxial anesthesia. No major neurologic sequelae were detected.

Scott and Hibbard7 conducted a retrospective British survey of more than 500,000 epidural procedures administered between 1982 and 1986, which detected a number of serious sequelae, including one epidural abscess, one hematoma, and one anterior spinal artery syndrome, but many of the diagnoses were presumptive.7 This survey probably failed to detect many minor lesions, but it was followed by a smaller prospective survey by Scott and Tunstall,8 which included some spinal anesthetics and involved a self-selected group of respondents. The investigators found no major neurologic disorders but a more believable number of what were termed mononeuropathies.

A French survey based on a questionnaire covering the years 1988 to 1993, and sent to all hospitals with maternity units, recorded one cranial subdural hematoma but no cases of epidural abscess or hematoma in 288,351 obstetric epidural procedures.9 Seven deaths were reported. Complications of spinal anesthesia were not included in this survey.

Both the Scott surveys7,8 and the French inquiry9 overlooked the need for a control group of laboring patients who did not receive neuraxial analgesia/anesthesia. The study by Holdcroft et al.10 avoided this pitfall; the denominator consisted of all 48,066 women who delivered in one region over a year, and every effort was made to detect genuine neurologic symptoms in the community. Because the women themselves were not sent questionnaires, however, the response rate could not be estimated. The investigators judged that only one case of paresthesia, without physical signs, could be attributed to epidural analgesia and none to spinal anesthesia. Peripheral nerve damage was more common. The most serious was one case of foot drop in a woman who had a spontaneous delivery of a large baby with inhalation analgesia only.

With the increase in popularity of spinal anesthesia, concern about the growing numbers of reports of paresthesias and possible root trauma led Holloway et al.11 to conduct a retrospective U.K. national survey of spinal and combined spinal-epidural (CSE) anesthesia in the 1990s. No difference in frequency of neuropathy was detected between Whitacre and Sprotte needles or between single-shot spinal and CSE techniques. Imprecise diagnoses made it difficult to differentiate anesthetic from coincidental causes, but after eliminating obvious obstetric or peripheral nerve palsies while otherwise erring on the pessimistic side, the investigators estimated that the incidence of neurologic sequelae was approximately 1 in 1000, including two cases of conus damage, one of meningitis, and the rest minor root palsies.

Two thorough local audit reports of immediate postpartum symptoms provided somewhat contrasting findings. One from Perth, Australia,12 involved prospective recording of complications in 10,995 parturients who received epidural analgesia, but it regrettably did not include a control group. The investigators detected only a single lasting neurologic problem. Although they termed the injury a traumatic mononeuropathy, it was apparently a radiculopathy, because it was attributed to a traumatic epidural procedure.

The second report, from Leeds, United Kingdom, involved 3991 women who delivered in one center in 1 year.13 Twenty-one women presenting with symptoms after neuraxial blockade were matched with 21 asymptomatic control patients who had also received neuraxial blockade and 21 who had not. Only 1 woman who had not had a neuraxial block presented with symptoms, and she was found to have foot drop after a vacuum extraction. Typical peripheral neuropathies occurred among those who delivered vaginally; sacral numbness was most commonly detected after cesarean delivery. All changes were transient, and none could be attributed to neuraxial anesthesia. Similar neurologic deficits were detected among the randomly selected, asymptomatic 21 control patients who had had no anesthetic intervention. In contrast, negligible deficits could be detected among the 21 asymptomatic control women who had had an anesthetic intervention. These results demonstrate that minor neurologic deficits are to be found postpartum quite frequently if sought, but only those who have had anesthetic intervention are likely to complain.

A prospective survey among 6057 women who delivered in 1 year in Chicago14 does not feature in Table 32-1 because the patients were not grouped by type of analgesia, but the findings of this survey corroborate those of the Leeds study.13 The incidence of lower limb nerve injuries was approximately 1% (24 lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, 22 femoral nerve, 3 peroneal nerve, 3 lumbosacral plexus, 2 sciatic nerve, 3 obturator nerve, and 5 radicular injuries).14 Significant risk factors identified by logistic regression analysis included nulliparity and a prolonged second stage of labor but not neuraxial anesthesia.

In a nationwide 10-month prospective French survey, only two so-called peripheral neuropathies and no major sequelae were detected among 5,640 spinal and 29,732 epidural procedures in obstetric patients.15 In contrast, in a retrospective Swedish national survey covering the years 1990 through 1999, Moen et al.16 reported nine serious sequelae among an estimated 200,000 epidural and 50,000 spinal procedures in parturients.

Ruppen et al.17 attempted to conflate the findings of various surveys to derive a consensus incidence of neurologic injury after obstetric epidural block. Unfortunately, this study took no account of the now widespread use of spinal and CSE techniques, denominators were calculated inaccurately, and the findings of surveys were not always interpreted correctly. For example, cranial subdural hematoma was counted as a spinal hematoma. Therefore, reliable information cannot be derived from this publication.

A U.K. national audit of neuraxial blocks, without controls, published in 2009, found that the risk for major complications was 6- to 14-fold higher for perioperative than for obstetric procedures. Among the obstetric patients, the risk was highest for CSE, intermediate for spinal, and lowest for epidural procedures.18

Several conclusions can be drawn from these surveys. Despite an increased cesarean delivery rate, obstetric palsies (albeit now more short-lived) still occur, and the reported frequency of neurologic sequelae depends on how hard one seeks them. The risk for transient mild deficits after childbirth may be quite high.13,14 A true figure for anesthetic complications cannot be calculated even from thorough surveys because (1) the diagnosis is rarely accurate; (2) definitions, severity, and duration are often ill defined; and (3) anesthesia provider skills vary. Table 32-1 demonstrates a variation in the incidence of neurologic sequelae from 1 in 3 for mild symptoms with no neuraxial block13 to 1 in 30,000 for epidural analgesia.16 Moreover, bias is created when more attention is paid postpartum to patients who have received neuraxial blockade than to those who have not.

Other Surveys

Modern surveys of neurologic complications of spinal and epidural anesthesia among nonobstetric populations may yield more reliable results but still lack sensitivity to detect all potential problems and are commonly conducted in relatively elderly and sick populations. Moreover, the occurrence of case clusters gives the lie to the existence of a “true” incidence of complications.16 Auroy et al.,15 Moen et al.,16 and Cook et al.18 surveyed mixed populations and found a lower incidence of serious sequelae in obstetric than in other patients. It is therefore invalid to extrapolate findings from one population to the other. The reported risk for neurologic problems varies greatly with the patient population, local practice and skill, completeness of detection, and inclusion criteria. Hence, it is meaningless to attempt to put any firm figure on the risk for neurologic complications after neuraxial anesthesia.

Peripheral Nerve Palsies

Postpartum nerve injury is often assumed to be due to neuraxial anesthesia, but peripheral nerve palsies, which generally have obstetric causes, are much more common, with a reported incidence between 0.6 and 92 per 10,000.19 They may arise from compression in the pelvis by the fetal head, or from more distal compression, the signs of which may be overlooked in the presence of neuraxial anesthesia. In contemporary obstetric practice, cesarean delivery is usually preferred to prolonged labor and difficult or forceps delivery. The incidence of pelvic nerve trauma and compression should therefore be lower than in years past. Surveys have shown that although obstetric palsies still occur,11,13,14 most are short-lived and less disabling than hitherto.2,3 Foot drop, however, is still reported,10,13,14,20 primarily in cases in which the effort to avoid cesarean delivery leads to vaginal delivery of a disproportionately large baby.10,13 Abnormal presentation, persistent occiput posterior position, fetal macrosomia, breakthrough pain during epidural labor analgesia, a prolonged second stage of labor, difficult instrumental delivery, and prolonged use of the lithotomy position may presage postpartum neuropathy.

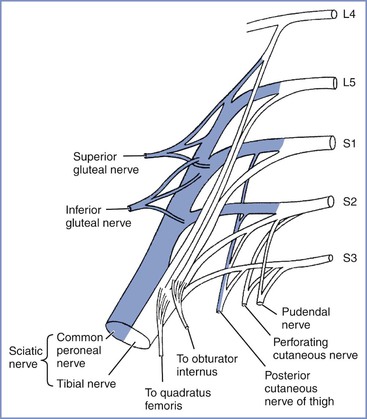

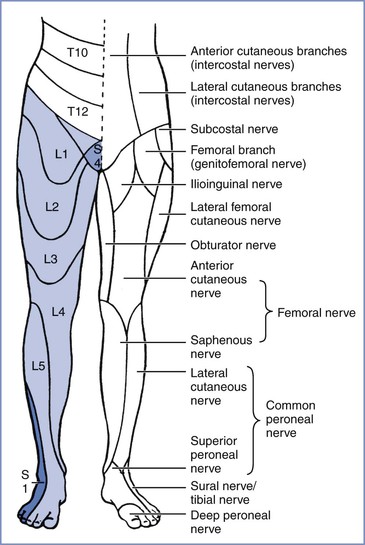

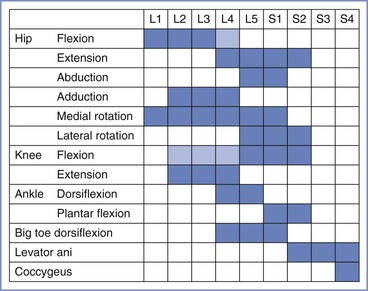

Reference to the distribution of spinal dermatomes and peripheral nerve sensory innervation clearly demonstrates the distinction between peripheral and central lesions (Figure 32-1). Spinal nerve root lesions are also manifested by weakness that involves several lower extremity joints and movements (Figure 32-2).

FIGURE 32-1 Segmental (right leg) and peripheral (left leg) sensory nerve distributions useful in distinguishing central from peripheral nerve lesions. (From Redick LF. Maternal perinatal nerve palsies. Postgrad Obstet Gynecol 1992; 12:1-6.)

FIGURE 32-2 The spinal segments involved in movements of joints in the leg. Lighter shading denotes a minor contribution. (Data from Russell R. Assessment of motor blockade during epidural analgesia in labour. Int J Obstet Anesth 1992; 4:230-4.)

Compression of the Lumbosacral Trunk

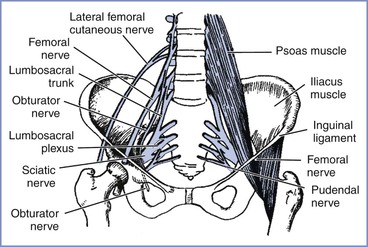

Compression of the lumbosacral trunk by the fetal head at the pelvic brim (Figure 32-3) preferentially affects the more medial fibers that make up the peroneal rather than the tibial nerve.19 In addition to weakness that predominantly affects ankle dorsiflexion (foot drop), compression of the lumbosacral trunk produces sensory disturbance mainly involving the L5 dermatome (see Figure 32-1). This palsy most often results from some cephalopelvic disproportion and is therefore typically seen after prolonged labor and difficult vaginal delivery.2,3,11–14

FIGURE 32-3 The principal nerves in the pelvis. The lumbosacral trunk (L4 to L5) and obturator nerve (L2 to L4) are vulnerable to pressure as they cross the pelvic brim, particularly in cases of cephalopelvic disproportion. The femoral (L2 to L4) and lateral femoral cutaneous (L2 to L3) nerves are particularly vulnerable in the lithotomy position, where they pass beneath the inguinal ligament. (Adapted from Cole JT. Maternal obstetric paralysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1946; 52:374.)

Obturator Nerve Palsy

The obturator nerve is susceptible to compressive injury as it crosses the brim of the pelvis or within the obturator canal (see Figure 32-3). The mother may complain of pain when the damage occurs, followed by weakness of hip adduction and internal rotation, with sensory disturbance over the upper inner thigh (see Figure 32-1). Cases are reported after both labor and cesarean delivery20–22; three were detected in a prospective study by Wong et al.14 Because the nerve would appear to be in a vulnerable position, it may be that injury occurs more often than is reported, but is misdiagnosed.

Femoral Nerve Palsy

Approximately one third of the postpartum palsies detected by Wong et al.14 were femoral nerve palsies. Dar et al.13 detected five cases in their small population, although the symptoms were transient. The femoral nerve does not enter the pelvis and is therefore not vulnerable to compression by the fetal head but is vulnerable to stretch injury as it passes beneath the inguinal ligament. Damage may result from prolonged flexion, abduction, and external rotation of the hips during the second stage of labor and also during procedures conducted in an excessive lithotomy position.23 The hips should therefore never remain continuously flexed during the second stage of labor. In femoral neuropathy, the nerve supply to the iliopsoas muscle is spared, so that some hip flexion is still possible. The patient with a femoral neuropathy may walk satisfactorily on a level surface but may be unable to climb stairs; the patellar reflex is diminished or absent.

Meralgia Paresthetica

Meralgia paresthetica is a neuropathy of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, a purely sensory nerve also known as the lateral cutaneous nerve of the thigh. First described more than 100 years ago, meralgia paresthetica is commonly encountered in pregnancy and childbirth.13,14 It may arise both during pregnancy, typically at about 30 weeks’ gestation, and intrapartum,14,24 in association with increasing intra-abdominal pressure. It may recur during successive pregnancies. The most likely cause is entrapment of the nerve as it passes around the anterior superior iliac spine beneath or through the inguinal ligament, where its vulnerability is increased by a large intra-abdominal mass or by retractors used during pelvic surgery. The compressive effect of edema may also contribute. Meralgia paresthetica manifests as numbness, tingling, burning, or other paresthesias affecting the anterolateral aspect of the thigh. The distribution is quite unlike that of a nerve root lesion (see Figure 32-1), yet the disturbance is commonly attributed to neuraxial blockade by those ignorant of neuroanatomy. The condition can be expected to resolve after childbirth; transient pain may be relieved by local infiltration analgesia.

Sciatic Nerve Palsy

Sciatic nerve palsy arises from compression of the nerve, usually in the buttock. It is not commonly mentioned in surveys or generally recognized as a complication of childbirth, possibly because it is mistaken for a lesion of the lumbosacral trunk. It gives rise to loss of sensation below the knee with sparing of the medial side and loss of movement below the knee. Posterior cutaneous nerve and gluteal function are preserved, implying damage distal to the lumbosacral plexus, where the gluteal nerves branch off the sciatic nerve (Figure 32-4). It has occurred during childbirth under neuraxial blockade, either from sitting in one position too long25 or from a hip wedge misplaced during cesarean delivery.25–27 Hypotension may be contributory. Three cases were detected by Wong et al.14 Despite the peripheral location of the lesions, neuraxial anesthesia cannot be exonerated, because the symptoms of nerve compression, which otherwise would have prompted a change of position, may be overlooked or wrongly attributed to local anesthetic-induced sensory blockade.

Peroneal Nerve Palsy

The common peroneal nerve is vulnerable to compression as it passes around the head of the fibula below the knee. It is also susceptible to damage while it still forms part of the sciatic nerve as it leaves the pelvis. Peroneal nerve palsy may be caused by prolonged squatting,28 sometimes popular in “natural childbirth,” by excessive knee flexion for any reason, by compression of the lateral side of the knee against any hard object, even the parturient’s hand,29 and by prolonged use of the lithotomy position. These risks are compounded by the presence of neuraxial blockade. When the peroneal nerve is damaged at the knee, there is sensory impairment on the anterolateral calf and the dorsum of the foot; foot drop may be profound, with steppage gait and weak ankle eversion, but plantar flexion and inversion at the ankle are preserved.

Compression as a Risk Factor for Peripheral Neuropathy

During pregnancy, nerve compression due to edema may be a factor in the genesis of several peripheral neuropathies, such as carpal tunnel syndrome, Bell’s palsy, and meralgia paresthetica.24,30,31 Anesthesia providers cannot be wholly absolved from responsibility for peripheral neuropathies, the signs of which may be overlooked or attributed to neuraxial anesthesia.26,29 Adverse factors can be minimized by attention to simple rules (Box 32-2). One group of patients, those with hereditary neuropathy with liability to pressure palsy, requires particular attention. In these women even relatively brief periods of immobility or pressure on any one site must be avoided.32,33

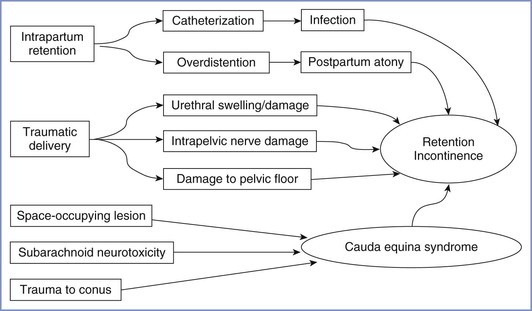

Postpartum Bladder Dysfunction

There are several mechanisms by which bladder function may be disturbed postpartum (Figure 32-5). In theory, neuraxial blockade (1) may provoke the need for bladder catheterization with increased risk for infection, (2) may allow bladder distention to go undetected, and (3) on very rare occasions, may be associated with cauda equina syndrome (see later discussion). However, several postpartum studies of bladder function have found no association with neuraxial analgesia34,35 or only a weak correlation between epidural analgesia and an increased residual volume immediately postpartum.36 In contrast, a prolonged second stage of labor, instrumental delivery, and perineal damage have been identified as significant factors for postpartum bladder dysfunction.34–36 In the previously described large survey of long-term symptoms after childbirth conducted in Birmingham, United Kingdom, no association was found between epidural analgesia and stress incontinence or urinary frequency.8,37 By far the most common cause of bladder dysfunction appears to be non-neurologic. Nevertheless, it must be part of the anesthesia provider’s responsibility to ensure that the bladder does not become overdistended either intrapartum or postpartum.

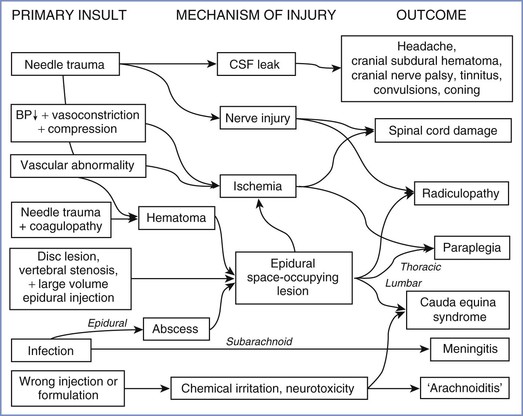

Central Nervous System Lesions

Lesions of the central nervous system (CNS) after childbirth have complex causes (Figure 32-6), which may be classified as traumatic (to nervous tissue, meninges, or blood vessels), infective, ischemic, or chemical (to nervous tissue or meninges). Anesthesia providers should bear in mind that even central lesions may have causes other than neuraxial block, the most obvious being a prolapsed intervertebral disc. Apart from sequelae of dural puncture, serious iatrogenic complications are remarkably rare.

Neurologic Sequelae of Dural Puncture

The subject of post–dural puncture headache is discussed in detail in Chapter 31. There are several other causes of severe postpartum headache, some of which have serious neurologic implications. Postpartum headache requires diagnosis first and foremost, followed by treatment that is curative rather than palliative.

Postpartum cortical vein and venous sinus thrombosis are more common than expected because of the hypercoagulable state of the blood.38–40 Cortical vein thrombosis has been associated with dural puncture and post–dural puncture headache. Headaches caused by meningitis, venous sinus thrombosis, preeclampsia, hypertensive encephalopathy, subdural hematoma, internal carotid artery dissection, and posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome may cause difficulty in diagnosis, particularly if they occur after epidural bolus injection, unintentional dural puncture, or administration of an epidural blood patch. Seizures may occur in patients with eclampsia, hypertensive encephalopathy, meningitis, or pneumocephalus but may also follow dural puncture or performance of an epidural blood patch.38–49

It is commonly assumed that headache after dural puncture will resolve spontaneously over time, but unfortunately a dural leak can persist and may occasionally have more serious consequences, including cranial nerve palsy and subdural hematoma. Neglected cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak has also been known to induce medullary and tentorial coning.50 Although serious problems are more likely to occur from unintentional dural puncture with a large epidural needle and a neglected headache, they may occasionally follow deliberate dural puncture with a small-gauge spinal needle.50

Cranial Nerve Palsy

Major loss of CSF, usually following unintentional dural puncture with a large needle, may cause a number of cranial nerve palsies; those affecting cranial nerves VI, VII and VIII are the most frequently reported.51–57 Because of its long course within the cranium, the abducens nerve (VI) is the most vulnerable. All cranial nerve palsies require prompt epidural blood patch, but even after the blood patch, recovery may be delayed. In the case of cranial nerve VIII dysfunction, tinnitus may become permanent.56,57 Trigeminal nerve dysfunction is usually a transient effect of high spinal blockade.

Cranial Subdural Hematoma

More seriously, reduced CSF pressure may cause rupture of bridge meningeal veins and result in cranial subdural hematoma, a potentially fatal condition that has been reported sporadically over many years.50 Palot et al.9 found one case in 288,351 obstetric epidural procedures; in 2000, Loo et al.4 identified eight obstetric cases, and more have been reported since.58–62 Although commonly believed to result only from neglect of a dural puncture with a large needle or a cutting spinal needle, subdural hematoma requiring craniotomy has been reported after puncture with a small-gauge, pencil-point spinal needle60 and after an unintentional dural puncture that had been appropriately treated with an epidural blood patch.58 Whenever headache persists after treatment with an epidural blood patch (particularly if the headache is accompanied by altered consciousness, seizures, or other focal neurologic findings), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is warranted to exclude subdural hematoma, which may be fatal without urgent surgery.

One case of cranial epidural hematoma arose after spinal anesthesia for removal of the placenta; the hematoma occurred after a seizure.63 Nothing was as it seemed, however; the seizure was not eclamptic, but rather epileptic, and the hematoma was not a result of spinal anesthesia.

Trauma to Nerve Roots and the Spinal Cord

Insertion of a spinal needle or epidural catheter is not infrequently accompanied by paresthesia that is sometimes painful. Although a flexible catheter is unlikely to do lasting damage to a nerve root in the epidural space, nerve roots in the subarachnoid space are more vulnerable.

Trauma Associated with Attempted Epidural Catheter Insertion

An epidural catheter may injure nerve roots either because it is inappropriately rigid64 or because an undue length is threaded and ensnares a root.65 A catheter seemingly threaded into the epidural space may lodge in an intervertebral foramen or even pass into the paravertebral space. In rare instances the epidural catheter and the artery of Adamkiewicz share the same foramen. If the epidural catheter is stiff enough to compress the artery within the unyielding foramen, the blood supply to the spinal cord may be impaired. This is a possible cause of anterior spinal artery syndrome. Clinical reports indicate that the condition resolves rapidly and completely if the catheter is withdrawn before permanent damage has occurred.66,67

Injury to the spinal cord may result from attempted identification of the epidural space in the presence of undetected spina bifida occulta or a tethered cord68 or as a result of an unsteady grip or uncontrolled advancement of the epidural needle. Insertion of an epidural catheter in an anesthetized patient greatly increases the risk for spinal cord damage, and catastrophic injury may occur with injection of fluid into the substance of the spinal cord.69

Trauma Associated with Spinal Anesthesia

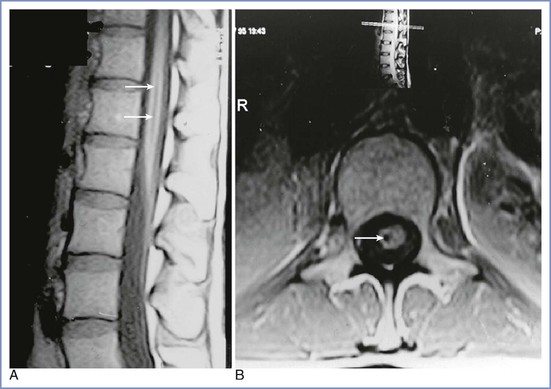

Insertion of a spinal needle below the level of the spinal cord sometimes causes brief radiating pain or paresthesia, which may be associated with persistent paresthesia in the same dermatomal distribution. Prolonged symptoms involving more than one spinal segment suggest damage to the spinal cord itself. Damage to the terminal portion of the cord (the conus medullaris) without intracord injection has also been reported in healthy conscious parturients receiving spinal or CSE anesthesia using a pencil-point needle.11,16,70,71 Typically, the patient complains of pain on needle insertion before any fluid is injected, often followed by the normal appearance of CSF from the needle hub, easy injection of the local anesthetic agent, and a normal onset of neural blockade. On recovery, there is unilateral numbness, which is succeeded by pain and paresthesia in the L5 to S1 distribution and foot drop, and in some cases urinary symptoms; sensory symptoms may last for months or years. The MRI appearance is one of a small syrinx or hematoma within the conus at the level of the body of T12 on the same side as the pain on insertion and subsequent leg symptoms (Figure 32-7).71 In the majority of cases, the anesthesia provider believed the interspace selected was L2-L3. In one patient who subsequently died of other causes, hematomyelia was confirmed at autopsy.72 Since a spate of cases of conus damage in the 1990s, the practice of spinal needle insertion may have been modified, but an abnormally long cord may still be damaged with the best of techniques.73

FIGURE 32-7 A and B, Magnetic resonance images of a conus medullaris lesion (arrows). (From Reynolds F. Damage to the conus medullaris following spinal anaesthesia. Anaesthesia 2001; 56:238-47.)

These injuries may have occurred for the following reasons:

• Anesthesia providers, accustomed to siting epidural needles and catheters, had forgotten the precautions necessary to avoid contact with the spinal cord during dural puncture. Moreover, the option to use an upper lumbar interspace was sanctioned by some reputable textbooks.74

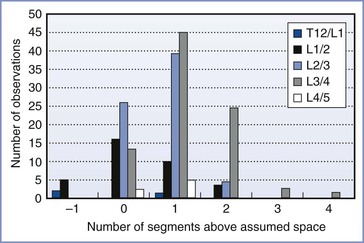

• Identification of lumbar interspaces was far from accurate. Studies showed that it was common to select a space that is higher than assumed by one, two, or even more segments (Figure 32-8).75,76 Anesthesia providers had little opportunity for feedback to improve their skill in interspace identification.

FIGURE 32-8 Identification of lumbar interspaces by Oxford anesthetists. The horizontal axis shows the position of the actual interspace identified on magnetic resonance imaging, relative to the assumed space, in 200 observations. (Data from Broadbent CR, Maxwell WB, Ferrie R, et al. Ability of anaesthetists to identify a marked lumbar interspace. Anaesthesia 2000; 55:1122-6.)

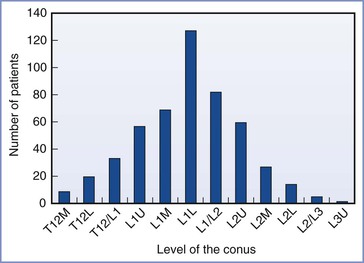

• Although the spinal cord typically ends level with the lower body of L1 or the L1-L2 interspace, the length varies (Figure 32-9).77 From the L1-L2 interspace, the needle tip can easily reach the conus in 27% of men and 43% of women.78

FIGURE 32-9 Variation in the level of the tip of the conus medullaris assessed by magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine among 504 consecutive adults. L, lower third of vertebral body listed; M, middle third of vertebral body listed; T12/L1, interspace between T12 and L1; U, upper third of vertebral body listed. (Data derived from Saifuddin A, Burnett SJ, White J. The variation of position of the conus medullaris in an adult population: a magnetic resonance imaging study. Spine 1998; 23:1452-6.)

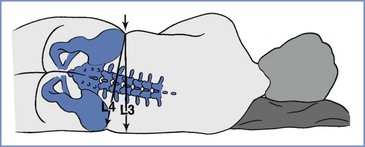

• The standard method of identifying lumbar interspaces involves the use of Tuffier’s line, the imaginary line joining the two iliac crests. This method can be inaccurate, however, particularly in obese or pregnant women (Figure 32-10). Moreover, even when accurately assessed, Tuffier’s line is an inconstant landmark.79 Although typically at the level of the L4 spinous process, it may lie anywhere between the L3-L4 and L5-S1 interspaces. Other means of identifying the interspace, such as counting down from C7 or finding the vertebra that is attached to the 12th rib, are tedious and of little help in obese patients.

FIGURE 32-10 Error that may arise if Tuffier’s line is judged in a pregnant patient in the lateral position, when a line is drawn perpendicularly from the upper iliac crest rather than through both iliac crests. In pregnant patients at term, the hips may have a greater width than the shoulders. The resulting cephalad pelvic tilt may lead to an error in the cephalad direction.

Medical students and residents are usually instructed to select the L4-L5 interspace for diagnostic lumbar puncture, but anesthesia providers have been more liberal in their approach. Given the inaccuracy of identification of lumbar interspaces and the variability of the position of the conus, it is both logical and prudent to insert a spinal needle below the spinous process of L3, or at least into a lower lumbar interspace, especially in women. Box 32-3 summarizes the problems and precautions in identifying lumbar interspaces and avoiding damage to the conus medullaris.

Space-Occupying Lesions of the Vertebral Canal

Space-occupying lesions of the vertebral canal include intraspinal hematomas (epidural or subdural), epidural abscess, and intraspinal tumors, any of which, within the rigid confines of the bony spinal canal, can cause dangerous compression of nervous tissue and its blood supply. Urgent laminectomy is required to avoid permanent neurologic damage. Delayed recognition and treatment (> 6 to 12 hours after onset of symptoms) may have a catastrophic outcome and grave medicolegal consequences.

Epidural analgesia in labor does not normally behave like a space-occupying lesion and produces no lasting deformation of the thecal sac on MRI.80 Nevertheless, in the presence of vertebral stenosis or lumbar disc protrusion, a large volume injected into the epidural space may tip the balance and produce signs of nervous tissue compression that normally resolve in a few hours.81,82

The neurologic deficit that may arise from a compressive lesion depends on the vertebral level; lower thoracic lesions are associated with leg weakness or paraplegia, and lumbar lesions with cauda equina syndrome, including urinary retention and incontinence. Back pain (often radiating to the legs) is a common feature.

Spinal Hematoma

Spinal hematomas may be classified as epidural, subdural, or subarachnoid.83 Keppel et al.83 found 613 cases of spinal hematoma published in the medical literature between 1826 and 1996, 461 of which were epidural, 25 subdural, and 96 subarachnoid. Spinal hematomas were described at all vertebral levels. Twice as many patients were male as female. Many patients were elderly and only five were pregnant (details unknown). The majority of cases (44%) were spontaneous or followed minor trauma, and 22.5% were related to coagulopathy or anticoagulant treatment; only 63 cases followed lumbar puncture or neuraxial anesthesia. Of these 63 patients, 26 were without coagulopathy.

Similarly, during pregnancy and the puerperium, spontaneous epidural hematoma is reported more frequently than hematoma associated with neuraxial blockade. Loo et al.4 found three cases (that may have been included in the earlier review83) and more have been reported in the 21st century.84–88 Epidural hematoma in pregnancy associated with coagulopathy but without neuraxial anesthesia is also reported.89,90 It has been suggested that pregnancy-induced structural changes in vessel walls, together with hemodynamic changes, may predispose to spinal hematoma.86

Epidural Hematoma after Neuraxial Blockade.

Incidence.

Epidural hematoma after neuraxial blockade typically causes neurologic deficit in elderly patients with arterial disease; it is very rare in obstetric patients, despite the engorgement and possible fragility of epidural veins. Nine surveys, covering 1,331,171 obstetric epidural procedures,* found two cases (see Table 32-1), one without confirmatory details7 and the other in a patient with HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelets) syndrome.16 This gives an incidence of 0.150 per 100,000 epidural procedures (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.018 to 0.543). Any estimate of the incidence of epidural hematoma in the surgical population is equally meaningless because, as with obstetric cases, it depends on how assiduously neuraxial blockade is avoided in the presence of coagulopathy and also on the incidence of vessel puncture, which in turn is affected by the skill of the anesthesia provider.

Causation.

Risk factors identified from comprehensive reviews of case reports include (1) difficult or traumatic epidural needle/catheter placement, (2) coagulopathy or therapeutic anticoagulation, (3) spinal deformity, and (4) spinal tumor.4,91,92 Antiplatelet therapy with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is believed not to increase the incidence of neurologic dysfunction after neuraxial anesthesia,93

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree