FIGURE 48-1 Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of a young child with congenital pseudarthrosis of the ulna in the setting of NF. Note is made of the tapered and sclerotic bony ends with dysplastic distal ulnar segment consistent with a congenital pseudarthrosis.

CLINICAL QUESTIONS

- What is neurofibromatosis (NF)?

- What are the clinical criteria by which NF is diagnosed?

- What are the orthopaedic manifestations of NF?

- What are the surgical indications for and principles of neurofibroma excision?

- In cases of pseudarthrosis of the ulna, what are the treatment options for surgical care?

- What are the potential complications of neurofibroma excision? Of free vascularized fibular grafting (FVFG) for congenital pseudarthrosis?

THE FUNDAMENTALS

Also known as von Recklinghausen disease, NF type 1 (NF1) is one of the most common human genetic disorders. Although the primary pathologic process involves altered neuronal cell growth, NF1 may present with a number of musculoskeletal and systemic manifestations. The effect on bones, nerves, skin, and other soft tissues may lead to alterations in growth, development, and function of the upper extremity, presenting a host of challenges to the pediatric hand and upper extremity surgeon.

Etiology and Epidemiology

Historically, NF was first described in 1793 by von Tilenau, though von Recklinghausen is credited with associating the clinical manifestations of this disorder with nerve tumors.1,2 One of the most common genetic diseases in humans, NF affects approximately 1:3,000 people and is inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion with near complete penetrance. Approximately one-half of all cases are due to sporadic mutation.

Mutations in the neurofibromin gene, localized to chromosome 17q11.2, are responsible for NF1.3 The NF1 gene locus is comprised of 350,000 base pairs and 59 exons, and its large size has been implicated in the frequency with which sporadic mutations occur.4 The gene encodes a 280-kDa cytoplasmic G-activating protein that regulates p221-RAS proto-oncogene function.5–7 While this protein is found throughout the body during development, it later becomes more specifically expressed in neuronal tissues.

These genetic abnormalities are distinct from mutations in the merlin or schwannomin gene, which have been attributed to NF type 2 (NF2) (so-called central NF).8,9 Diagnostic criteria include the presence of eight or more nerve masses and a positive family history of a first-degree relative with NF2. It affects approximately 1:40,000 individuals and usually presents with hearing loss in young adults. While NF2 typically causes tumors of cranial nerve VIII (including the bilateral vestibular schwannomas resulting in hearing loss), meningiomas, ependymomas, and peripheral nerve tumors, musculo-skeletal manifestations are uncommon. As a result, these patients rarely come under the care of the pediatric hand and upper extremity surgeon.

Furthermore, segmental NF represents yet another uncommon variant of NF.10,11 Segmental NF typically involves multiple plexiform neurofibromas limited to a single body part without crossing the midline and devoid of the systemic clinical manifestations common to NF1.

Clinical Evaluation

Silence is golden when you can’t think of a good answer.

—Muhammad Ali

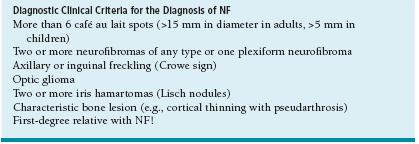

Neurofibromas refer specifically to mixed cell tumors arising from peripheral nerve sheath cells, rich in Schwann cells, fibroblasts, mast cells, and endothelial cells. The clinical diagnosis of NF1 is made based upon a number of established clinical criteria (Table 48-1).1,12 In general, NF is diagnosed in the presence of two of the following clinical features: (1) more than six café au lait spots measuring at least 5 mm in diameter in children, (2) two or more solitary neurofibromas or one plexiform neurofibroma, (3) axillary or inguinal freckling (the so-called Crowe sign), (4) the presence of optic gliomas, (5) two or more iris hamartomas (Lisch nodules), (6) characteristic skeletal lesions (e.g., long bone pseudarthrosis), and/or (7) a first-degree relative with NF1.

Table 48.1

Clinical diagnosis of NF1

From Feldman DS, Jordan C, Fonseca L. Orthopaedic manifestations of neurofibromatosis type 1. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 18:346–357.

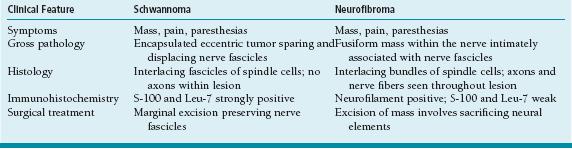

Histologically, neurofibromas appear as whorls of interlacing spindle-shaped cells, though they stain poorly for S-100 and Leu-7 (Table 48-2). Technically benign, these lesions demonstrate varying morphologies, unpredictable growth patterns, and often infiltrate and involve the nerve fascicles and axons themselves.13 Clinically, the lesions manifest themselves as solitary palpable subcutaneous nodules, often with overlying discoloration. Although rarely appreciated at birth, neurofibromas usually become apparent in late childhood (e.g., at the end of the first decade of life). Solitary neurofibromas account for roughly 85% of all upper limb cases.

Table 48.2

Features distinguishing schwannoma from neurofibromas

Adapted from Forthman CL, Blazar PE. Nerve tumors of the hand and upper extremity. Hand Clin. 2004;20:233–242, v.

Plexiform neurofibromas, in contrast, are characterized by diffuse, raised, hyperpigmented, cutaneous lesions with boggy or “bag-of-worms”–type consistency. Genetic mutations similar to those seen in NF1 of chromosome 17 are seen in plexiform neurofibromas; indeed, the presence of plexiform neurofibromas is almost always associated with NF1.14 Although neurofibromas are typically nonpainful, the presence of pain or tenderness— particularly with plexiform lesions—raises the concern of malignant transformation, usually into malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNST).15–18 Indeed, owing to the genetic basis of the disease, patients with NF are at higher risk for other malignancies as well, including melanoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, astrocytomas, and hematologic malignancies.

In addition to these classic and diagnostic clinical manifestations, NF may cause bony lesions resulting in presentation to a pediatric hand and upper extremity surgeon. Perhaps the most common and severe orthopaedic issue related to NF is pseudarthrosis of the long bones, most commonly the tibia, fibula, ulna, and clavicle.19 While only 5% to 10% of patients with NF will demonstrate bony pseudarthroses, up to 75% with pseudarthroses will have NF1.13,20,21 These patients typically present with deformity of the affected limb, often with purported history of prior fracture nonunion. While the exact patho-physiology is unknown, these bone lesions are characterized radiographically by nonunion sites devoid of typical periosteal reaction and callus formation, with dysplasia, sclerosis, and narrowing of the adjacent bony segments (see Coach’s Corner) (Figure 48-1). When left untreated, the condition may result in bowing deformities of the limb (particularly the leg). Given the abnormal biology of these lesions, it is common to see persistent “nonunion” after prior attempts at conventional fracture healing, including casting, internal fixation, and autogenous or allograft bone grafting.

Furthermore, given that NF1 is due to a known neu-rofibromin gene mutation, genetic testing may assist in diagnosis. The so-called protein truncation test is utilized to detect abnormally truncated, or shortened, proteins that result from the inherited or acquired genetic mutation(s).22 This test, however, is positive in only 70% of patients, making NF still a diagnosis assigned often by virtue of clinical criteria.

In addition to careful clinical history, physical examination, and plain radiography, advanced imaging such as computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may assist in diagnosis and treatment. Advanced three-dimensional imaging will provide improved localization as well as gross descriptive features of the mass(es) in question. Even with current imaging technology, however, the distinction between nerve tumors and nerve sheath or other neoplasms (specifically, neurofibroma vs. schwannoma) may not be able to be made (Table 48-2).23

A number of other hyperpigmentation or overgrowth syndromes may be confused with NF and should be included in the differential diagnosis of these patients. These conditions include but are not limited to McCune Albright syndrome, Leopard syndrome, and hemihypertrophy due to vascular or lymphatic malformations.

Given the genetic diagnostic testing available, as well as the multiple other organ systems that may be involved, formal genetic consultation is recommended in cases of established or suspected NF.

Surgical Indications

Surgery is generally indicated for pain and functional limitations due to a nodular or plexiform neurofibroma. In cases of patients with increasing pain or tenderness, surgery is indicated to rule out malignant transformation, particularly in cases of plexiform lesions. (Immunohistochemistry looking at ki-67 and S-100 staining has been utilized to distinguish MPNST from neurofibromas.)24 Finally, surgical excision and/or skeletal reconstruction is indicated in patients with secondary bony deformity or pseudarthroses.

SURGICAL PROCEDURES

Excision of NF Nerve Lesions

Excision of NF Nerve Lesions

The harder you work, the luckier you get.

—Gary Player

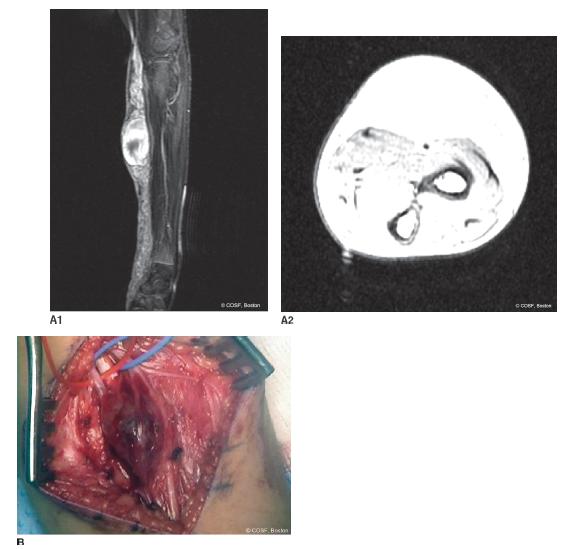

In patients with nodular neurofibromas associated with pain, enlarging size, or concern for malignant transformation, surgery is performed under general anesthesia (Figure 48-2). In keeping with oncologic surgical principles, extensile longitudinal surgical incisions are utilized. The normal neurovascular structures are identified proximal and distal to the mass, and the confirmation is made of the peripheral nerve involved.

FIGURE 48-2 Excision of a solitary, nodular neurofibroma. A: Preoperative sagittal (A1) and axial (A2) MRI images of a patient with a large, painful forearm neurofibroma. B: Intraoperative photograph demonstrating the lesion in situ.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree