Neonatal Urinary Tract Infections

INTRODUCTION

Urinary tract infections (UTI) in the neonate pose a number of difficulties for the clinician. Symptoms are vague and overlap with a variety of other conditions. Accurate diagnosis requires testing of urine, which necessitates invasive techniques in the newborn child. The development of a UTI may be associated with the presence of other factors that increase the likelihood of pyelonephritis and subsequent renal scarring. In addition, significant ambiguity exists within the medical community about when further testing is necessary, which tests to obtain, and the appropriate timing of such testing. With these issues in mind, we address the basic workup and treatment of UTI in the neonate and briefly discuss some current controversies.

DIAGNOSIS

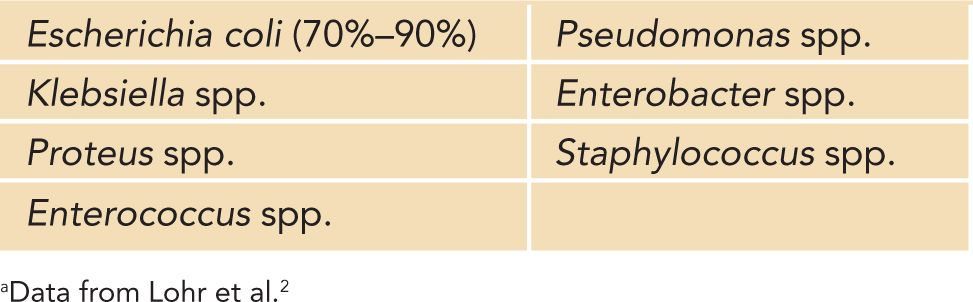

Urinary tract infection occurs in 0.1%–0.4% of infant girls, 0.702% of uncircumcised infant boys, and 0.188% of circumcised infant boys.1 UTI is more common in premature (2.9%) and very low birth weight (4%–25%) infants in comparison to full-term infants (0.7%).2 One of the most difficult aspects of UTI in neonates is the lack of any visible signs early in the process. Although adults and older children may experience symptoms such as frequency, urgency, and dysuria at the beginning of a UTI, neonates typically present with a fever or general irritability. The history may include malodorous urine or general fussiness or may consist only of fever. The presence of a fever without an identified focus in a neonate prompts workup, including a full physical examination and obtaining samples of urine, blood, and cerebrospinal fluid for analysis and culture.3 Admission to the hospital and initiation of intravenous antibiotics are routine. As in older children, bacteria of enteric origin cause most UTIs, with Escherichia coli the most common.4 Table 101-1 lists some of the most common bacteria causing UTIs in children.

Table 101-1 Common Bacteria Causing Urinary Tract Infections in Children a

Physical examination in the neonate with a UTI is unlikely to provide any additional information, although the external genitalia should certainly be assessed. The presence of an intact foreskin and degree of physiologic phimosis should be noted in boys, as well as the presence of labial adhesions in girls. These anatomic considerations may complicate the accuracy of urine samples, as well as be potential areas of intervention for prevention of future infections. In addition, evaluation of the lower spine for a sacral dimple should be performed, with ultrasonography of the spine if a deep lesion is identified.

Accurate sampling of urine in neonates requires a sample to be obtained prior to antibiotic administration using either suprapubic aspiration (SPA) or catheterization of the urethra. SPA presents the least opportunity for contamination of a specimen but is the most invasive approach. Briefly, after cleansing the suprapubic area, a fine needle (21 gauge) is passed 1 fingerbreadth above the pubic bone, angling down toward the pelvis while aspirating.5 The use of ultrasound guidance may increase the accuracy and safety of this procedure.6 Because of the invasive nature of this approach, informed consent should be obtained whenever possible. Urethral catheterization is a less-invasive procedure, although it carries a higher risk of contamination from bacteria in the distal urethra and on the external genitalia, particularly in uncircumcised boys and girls with labial adhesions. Despite employment of sterile technique, the risk of contamination with catheterization leads to a sensitivity of 95% and a specificity of 99% in comparison to SPA.7 Bagged urine is not appropriate for diagnosis of UTI in the neonate because of the high rate of falsely positive specimens.8

Evaluation for leukocyte esterase and the presence of nitrates on a urinalysis should be performed on a fresh specimen, as well as microscopic evaluation for the presence of white blood cells and bacteria. When the presence of leukocyte esterase and nitrates is positive on urinalysis, particularly in the presence of bacteria on microscopy, there is a high probability of a UTI. When urinalysis is suspicious or there is clinical concern for UTI, the urine should be sent for culture and sensitivities. Additional blood work, including a complete blood cell count with differential and C-reactive protein (CRP) value, may be helpful in assessing the neonate’s overall condition and the severity of the infection, as well as in monitoring the success of treatment.

TREATMENT

Treatment of a suspected UTI in the neonate should consist of initiation of antibiotic therapy with an age-appropriate intravenous antibiotic after urine is obtained for culture. Despite data suggesting that delay in treatment of UTI may not increase the risk of renal scarring,9 it is generally accepted that treatment should be initiated as soon as possible to minimize the risk of renal damage. Outpatient therapy for pyelonephritis is well accepted in pediatric literature10 and has been successfully demonstrated in 1- to 3-month-olds using intravenous antibiotics11; however, neonates will invariably require admission to the hospital. Intravenous fluids are initiated to replace losses from fever and decreased oral intake. After obtaining appropriate specimens for culture, empiric intravenous antibiotics are initiated, with later conversion to oral therapy once the offending organism and its antibiotic sensitivities are known.

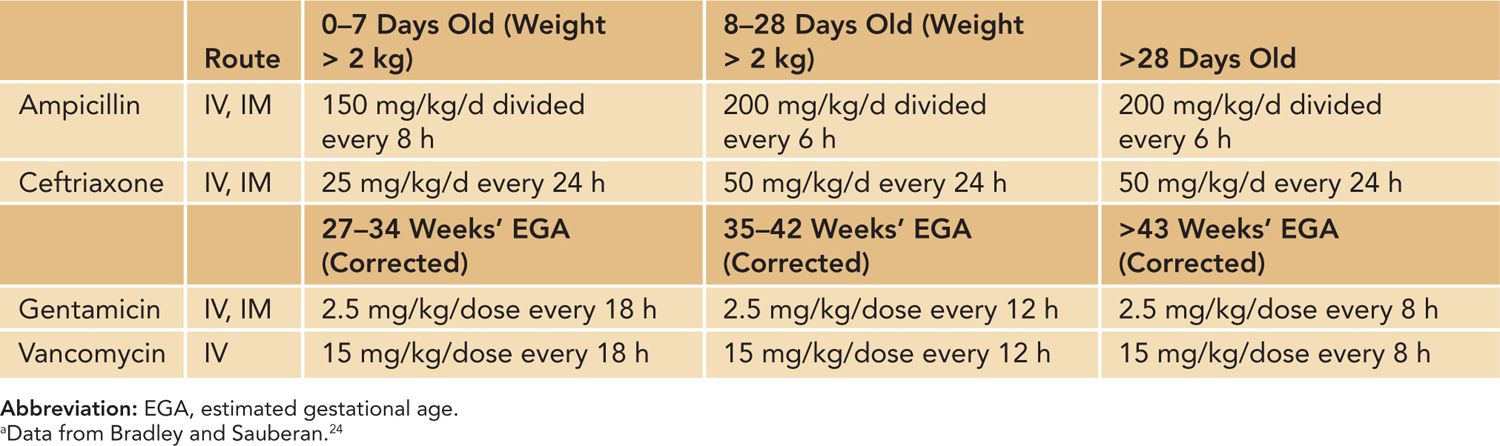

Oral and intravenous antibiotic choices are limited in this age group because of medicine side effects and neonatal physiology. The initial antibiotic choice should cover bacteria that frequently cause UTI (most commonly Escherichia coli, as listed in Table 101-1) and with knowledge of local resistance patterns.4,12 A cephalosporin (such as ceftriaxone) or a penicillin derivative (ampicillin, etc) is a common empiric choice, with consideration of the addition of an aminoglycoside such as gentamicin to broaden coverage. Table 101-2 lists commonly used empiric intravenous antibiotics. Once oral therapy is initiated, generally after sensitivities are known and the patient is improving, penicillin derivatives and cephalosporins are the most commonly used antibiotics. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, an antibiotic commonly used to treat UTIs in children, is not appropriate in the first 2–3 months of life, and the same holds true for nitrofurantoin. Furthermore, nitrofurantoin is not an acceptable antibiotic for the febrile infant with a UTI as it does not reach adequate serum/tissue levels, making it an unacceptable choice for pyelonephritis. Ciprofloxacin is approved for use in complicated UTIs in children but is generally reserved for when there are no other oral options.

Table 101-2 Some Common Parenteral Antibiotics Used for Urinary Tract Infections in Neonatesa

In its most recent recommendation, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) sought to determine an optimal duration of antibiotic therapy based on the current literature.8 Although shorter durations (1–3 days) were inferior in a meta-analysis14

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree