Nasal Foreign Body Removal

Jonathan E. Bennett

Introduction

Nasal foreign bodies are a common problem among pediatric patients. Children have a sincere curiosity about placing objects in body orifices, and the nose seems to be a favorite choice for this behavior. At times, the diagnosis will be obvious, as the parent’s presenting complaint will be “He stuck something in his nose.” The task at that point is to find and remove the offending object. Diagnosis of an intranasal foreign body in a child, however, can be subtle when the parent has not witnessed the object being inserted. The classic presentation in this situation is an unexplained, foul-smelling nasal discharge that is unilateral and persistent. Other less specific complaints include chronic sinusitis, recurrent epistaxis, and halitosis (1,2,3,4). Body odor in a child also has been reported as a presenting complaint for intranasal foreign body (5,6). In addition, objects may be found incidentally, often during routine radiographic procedures (7,8). It is not unusual for the patient to be evaluated on multiple occasions with the same symptoms before the correct diagnosis is made. The physician must therefore maintain a high index of suspicion to detect this problem.

A veritable encyclopedia of small objects have been removed from the noses of children (9,10). Common items include toy parts, beads, tissue paper, and foam rubber (2). More recently, button batteries (i.e., those used in watches, calculators, and electronic toys and games) have increasingly been found as intranasal foreign bodies (11,12). These small alkaline batteries are a special concern, as they can cause liquefaction necrosis, leading to severe local tissue destruction (11). Objects that are hygroscopic, such as seeds or beans, may enlarge substantially as they absorb moisture from the nasal cavity, making extrication more difficult. Less commonly, animate objects (insects) may become lodged in the nose (13).

Goals for the physician suspecting this diagnosis are threefold: to conduct a thorough inspection of the nasal cavity, to maximally visualize the object (assuming one is found), and to remove the object while causing as little trauma (both physical and emotional) as possible. The difficulty of achieving these goals depends on several factors, including the size, shape, and location of the object; the level of cooperation from the child; and the skill of the physician. In cases of pediatric nasal foreign bodies, 90% occur in children under 4 years of age (2). Achieving adequate cooperation with these younger patients often is the primary factor determining the success or failure of the procedure.

Several techniques have been advocated for removing nasal foreign bodies. Most are similar to methods used for retrieving foreign bodies from the external auditory canal (see Chapter 54). In general, removal should be performed only by a physician, because a failed attempt can result in advancing the object further into the nasal cavity, making subsequent attempts far more difficult. In addition, younger children become much more fearful and uncooperative after an initial attempt is unsuccessful. The procedure should be performed in a setting that has proper lighting, suction, and a variety of specialty instruments, including a right angle, an alligator forceps, and a curette. Airway equipment should be readily available in the unlikely event that an object is aspirated into the proximal airway.

Anatomy and Physiology

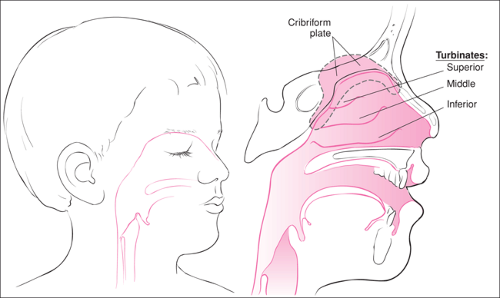

There are a few points about the anatomy of the nasal cavity that are important to keep in mind when attempting foreign body removal (Fig. 59.1). One is that the turbinates are essentially perpendicular to the face rather than parallel to the nasal bone. Instruments inserted into the nose should therefore be oriented in an anteroposterior (i.e., straight in) direction,

perpendicular to the plane of the face. Additionally, objects lodged superiorly and medially to the middle turbinate are precariously close to the cribriform plate. The clinician should not attempt removal from this area without involving an otolaryngologist. Inferior and medial to the middle turbinates are the nasal ostia, which drain the maxillary and anterior ethmoid sinuses. Foreign bodies may occlude these and lead to sinusitis (3). Persistent nasal discharge after the clinician is certain that the foreign body has been completely removed may be due to this cause. The patient should be started on an appropriate oral antibiotic regimen after the possibility of a retained foreign body has been excluded. Finally, the nasal septum consists of a thin cartilaginous plate with a closely adherent perichondrium and mucosa (see Fig. 57.1). This mucosa, which is lined with a rich vascular network, is thinner and more likely to bleed in children than adults. Bleeding is especially common at the Kiesselbach plexus in the Little area of the anterior nasal septum. Special care should be taken to prevent any significant injury to the septal mucosa, as this may result in bleeding to an extent that visualization and removal of a foreign body become impossible. Parents should be warned that minor bleeding after this procedure is common and generally benign.

perpendicular to the plane of the face. Additionally, objects lodged superiorly and medially to the middle turbinate are precariously close to the cribriform plate. The clinician should not attempt removal from this area without involving an otolaryngologist. Inferior and medial to the middle turbinates are the nasal ostia, which drain the maxillary and anterior ethmoid sinuses. Foreign bodies may occlude these and lead to sinusitis (3). Persistent nasal discharge after the clinician is certain that the foreign body has been completely removed may be due to this cause. The patient should be started on an appropriate oral antibiotic regimen after the possibility of a retained foreign body has been excluded. Finally, the nasal septum consists of a thin cartilaginous plate with a closely adherent perichondrium and mucosa (see Fig. 57.1). This mucosa, which is lined with a rich vascular network, is thinner and more likely to bleed in children than adults. Bleeding is especially common at the Kiesselbach plexus in the Little area of the anterior nasal septum. Special care should be taken to prevent any significant injury to the septal mucosa, as this may result in bleeding to an extent that visualization and removal of a foreign body become impossible. Parents should be warned that minor bleeding after this procedure is common and generally benign.

Indications

A thorough inspection of the nasal cavity is obviously indicated whenever a child has reportedly placed a foreign body in the nose. This information may come from a parent or other caretaker, a sibling, or the child. As described previously, other complaints that should prompt suspicion of an intranasal foreign body include a persistent nasal discharge (particularly when unilateral), recurrent epistaxis, and halitosis (1,2,3,4). Diagnosis of clinical sinusitis, a common finding in the outpatient setting, is often based on a history of purulent nasal discharge for longer than 7 to 10 days. These children also should be routinely evaluated for a nasal foreign body (3). A more exotic presentation, such as body odor in a young child, which would be unusual before the development of apocrine glands during adolescence, should cause the physician to at least consider the diagnosis of a nasal foreign body as one possibility (5,6).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree