18 Multifetal Pregnancy E. Albert Reece Because of their higher rates of perinatal morbidity and mortality compared with single-birth pregnancies, multifetal pregnancies present a significant challenge to OB/ GYN practitioners. Multifetal births are often complicated by low birth weight, fetal growth restriction, placental and cord abnormalities, pre-eclampsia, anemia, preterm labor, and an increased risk of infant mortality. This increased risk of fetal morbidity and mortality associated with multifetal pregnancies is matched by a similarly increased maternal risk for a variety of complications, including hypertension, anemia, and abruption. For these reasons, pregnancies that involve more than one fetus require especially close monitoring, particularly during the antepartum period when intervention is most likely to be effective in minimizing such problems. Amnionicity: Refers to the number of amniotic sacs. The amniotic sac is the pouch, or sac, in which the fetus develops. Aneuploidy: A genetic status characterized by cells having an abnormal number of chromosomes. Genetic syndromes caused by an extra or missing chromosome are among the most widely recognized genetic conditions. Down syndrome is a well known example. Chorionicity: A chorionicity scan is used to distinguish between twins that share a placenta and those who have separate ones. For example, in a dichorionic twin pregnancy, each developing fetus has its own placenta. Fraternal dizygotic siblings: This term refers to multiple-birth siblings resulting from the fertilization and implantation of more than one egg. Fraternal dizygotic siblings are not genetically identical. Instead they have what is known as “coequal” genetic similarity, which is the same as any other full siblings do. Hydramnios: The condition of having excessive amniotic fluid, sometimes referred to polyhydramnios. Inadequate volume of amniotic fluid is referred to as oligohydramnios. Identical montozygotic siblings: This refers to one egg being fertilized and the resulting zygote splitting into more than one embryo. Identical siblings therefore have the same genetic material. Multiple birth: This expression is used only when more than one fetus is carried to term in a single pregnancy. Different names have been assigned to babies that are born to a woman giving birth to multiples, depending on the number of live offspring, such as twins, triplets, quadruplets, quintuplets, etc. Multifetal pregnancy: This term is used for a pregnancy that involves more than one fetus. Placentation: This term refers to the formation, structure, or arrangement of a placenta or placentas. The function of placentation is to transfers nutrients from the mother to the growing embryo. Polyzygotic birth: In some multiple births, it is possible for a combination of identical and nonidentical births. For example, a set of triplets may have one fraternal baby from one egg, plus two identical twins from a second egg. The ability to diagnose a multifetal pregnancy early on is crucial to developing an effective antepartum management strategy. Once a multifetal pregnancy is suspected, ultrasonography, which is very sensitive for this purpose and has a detection rate approaching 99.3%, should be performed at the earliest possible gestational age. It will not only detect the number of fetuses but also other fetal health indicators, including placentation, amnionicity, and chorionicity. It is easiest to determine amnionicity and chorionicity in the first trimester and becomes increasingly difficult and less accurate as the gestation matures due to progressive thinning of the membrane and fetal crowding. Ascertaining these parameters is important because monochorionic pairs, which account for 20–33% of twin gestations, have a 2.5 greater relative risk of perinatal mortality than single-fetus pregnancies. They also are at increased risk of neurologic problems associated with twin—twin transfusion syndrome (see Etiology and Pathogenesis below) and demise of a co-twin in utero. Dichorionicity is established by ultrasound imaging of two separate placentas or fetuses of different gender. If these characteristics are not easily discernable, another tell-tale sign of dichorionicity is a piece of chorionic tissue projecting between the layers of the dividing membrane (i.e., the lambda or twin-peak sign) (Fig. 18.1). If this feature is absent, then it indicates monochorionicity. The thickness of the intertwin membrane has been used to predict chorionicity. However, this method is much less reliable. If chorionicity cannot be reliably established, the physician should consider more invasive testing. Monoamnionicity can ruled out by visualizing the presence of a membrane between the fetuses. Ultrasound imaging also is valuable for detecting the presence of any fetal anomalies. In the past several decades, multiple births have become significantly more prevalent due to the greater reliance on assistive reproductive technology (ART), especially among women delaying childbirth until their 30s and 40s. The most common form of human multiple birth is twins (two babies). Twins are relatively common and occur on average 13 times per 1000 maternities, though the twinning frequency varies over time and geographic location. Due to the dramatic increase in the use of ART between 1981 and 1997, the overall twinning birth rate in the United Stated has increased almost 40%, while that rate of higher order births has increased almost 360%. This same trend for twins and higher order births has been seen in other developed countries, including Great Britain, France, and Canada (Table 18.1). Fig. 18.1 Ultrasound image of a dichorionic pregnancy The arrow points to the characteristic lambda peak There have been a few cases of higher order births up to octuplets (eight babies), with all siblings being born alive. However, the largest multiple birth delivery in which the babies survived more than a few days were septuplets, the first of which occurred in 1997. The largest set to have even a single member survive is octuplets, which were born in 1998 to a couple in Texas (seven of the eight babies survived). There have been a few sets of nonuplets (nine) in which a few babies were born alive, though none lived longer than a few days. There even have been cases of human pregnancies that started out with ten, eleven, twelve, and even fifteen fetuses. However, there are no known instances of a live birth in such pregnancies. Most of these higher-order pregnancies were the result of fertility medications and ART, although in 1992 a set of duodecaplets (twelve) was conceived spontaneously (without the aid of fertility treatments) in Argentina. The birth rate of monozygotic twins is approximately 4 per 1000 births and is constant worldwide. In contrast, dizygotic twinning is associated with multiple ovulation, and its frequency varies among races within countries and is affected by maternal age. It increases from 3 per 1000 births in women younger than 20 years old to 14 per 1000 births in women aged 35–40 years and declines thereafter. The highest birth rate of dizygotic twins occurs in African nations, and the lowest birth rate of dizygotic twins occurs in Asia. The Yorubas of western Nigeria have a birth rate of 45 twins per 1000 live births, and approximately 90% are dizygotic. Many factors contribute to the recent increase in the prevalence of multiple pregnancies. The principal causes, however, are advancing maternal age and infertility treatments. As women get older, their chance of having “multiples” doubles. Women between 20 and 24 years of age have twins at the rate of approximately 22.4 per 1000 live births, whereas women between 40 and 44 years have twins at the rate of 51.3 per 1000 births. Women are also having children later in life. For example, in 2003 the birth rate for women between 40 and 44 years of age was approximately 8.7 births per 1000 compared to 3.9 births per 1000 among women in the same age group in 1980. Both environmental and genetic factors contribute to the tendency to conceive spontaneous dizygotic twins. Variations in these two factors are mostly attributed to the diferences in dizygotic twinning rate, since the monozygotic twinning rate is relatively constant. For example, mothers of dizygotic twins report significantly more female family members also with dizygotic twins than mothers of monozygotic twins. In addition to genetics, advanced age and increased parity also are known risk factors for dizygotic twins. Recent research has demonstrated that taller mothers and mothers with a high body mass index (BMI >30) are at greater risk of dizygotic twinning. Seasonality, smoking, oral contraceptive use, and folic acid also have been associated with an increased risk of twinning. However, these associations have not been found to be highly statistically significant. Genomic analysis has identified multiple genes that appear to contribute to the risk of twinning. Mutations in one of these genes—known as growth differentiation factor 9, or GDF9–occur significantly more frequently in mothers of dizygotic twins. However, the mutations are rare and only account for a small part of the genetic contribution for twinning. According to studies, 30–40% of pregnancies in the United States with three or more births occur because physicians implant more than the recommended number of embryos during in vitro fertilization. This practice places both the mother and fetus at greater risk for adverse outcomes. Multiple births are linked to a greater risk of premature birth, low birth weight, and other complications, such as cerebral palsy in the infant and pregnancy-related high blood pressure and postpartum depression in the mother. A number of European countries, including the United Kingdom, Germany, Sweden, and Switzerland, have banned the implantation of more than three embryos in the womb. In contrast, the United States only offers a voluntary guideline, which many doctors choose not to follow. Some doctors say they implant more than three embryos if a woman’s embryos are inferior. However, competition with other clinics and pressure from patients for high success rates also appear to play a role in this decision. A woman’s body must make many more physiological adjustments to multiple gestations than to a singleton pregnancy. For example, the size of her uterus must increase much more, which results in the abdominal organs becoming more compressed or displaced. Also, the diaphragm can be elevated, compressing the lungs. As a result of the abnormal size and weight of the larger uterus required for multiple pregnancies, the mother often experiences more pressure symptoms and more difficulty in ambulating and performing daily tasks. Furthermore, with a single fetus, a woman’s blood volume will increase by 40–50% in late pregnancy. In contrast, if she is carrying twins, her blood volume will increase by 50–60% (an extra 500 mL). In addition, compared with a singleton pregnancy, the increase in red cell mass in multiple gestations is less, thus producing a more pronounced “physiological anemia.” A woman carrying more than one fetus must also increase her cardiac output compared with a singleton gestation. This increased cardiac output in a twin pregnancy occurs primarily during the second and third trimesters and is the result of increased heart rate and higher stroke volume. Multifetal pregnancies also are complicated by an increase in the incidence of hypertensive disorders, which tend to occur earlier and be more severe than in singleton pregnancies. In a multifetal pregnancy, all of the fetuses are at increased risk of premature delivery, abnormal presentation and position, and hydramnios. In addition, they all have an increased risk for a prolapsed cord, premature separation from the placenta, and hypoxia. Also, during delivery, they may be injured by manipulation or may sufer ill-effects from prolonged anesthesia. Twinning and higher order pregnancies also are more prone to restriction, competition for nutrients, and cord compression and entanglement compared with singleton pregnancies. Monozygotic twins tend to be smaller and are significantly more prone to fetal demise in utero than dizygotic twins. Although it is well known that twin pregnancies carry higher risks for adverse consequences than single pregnancies, some types of twins—particularly those connected to a single (monochorionic) placenta—may face even higher risks. For monochorionic twins, the risks of serious, life-threatening complications are up to 10 times higher than for those twins who have one placenta each (i.e., dichorionic twins). The dangers in monochorionic twins are caused by the fact that the circulations of the twin pair are usually connected with each other via the placenta. The most serious complication with monochorionic placentas is a condition known as “twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome” in which blood is shunted from one fetus to the other through blood vessel connections in a shared placenta (Fig. 18.2). Over time, the recipient fetus receives too much blood, which can overload the cardiovascular system and cause too much amniotic fluid to develop. The smaller donor fetus meanwhile receives inadequate blood flow and has low amounts of amniotic fluid. This syndrom occurs in about 15% of twins with a shared placenta. Fortunately, it is possible to distinguish between monochorionic and dichorionic twins by ultrasound exam in the first and early second trimesters and to take steps to prevent such complications. Fig. 18.2 When twin fetuses share a single placenta, it can lead to twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome, in which one twin receives too much blood while the other receives too little, leading to potentially severe complications for both In places where ultrasound exams are not routinely administered during the first trimester of a pregnancy, the early diagnosis of a multifetal pregnancy is highly dependent on the physician’s ability to recognize predisposing factors during history-taking. A uterine size clinically estimated to be greater than expected, a history of assisted reproduction, or an elevated maternal serum a-fetoprotein level (see below) are enough to warrant further investigation. There are a number of tell-tale signs that a woman is carrying more than one fetus. She often will exhibit earlier and more severe symptoms of a normal pregnancy, including pressure on the pelvis, nausea, backache, constipation, hemorrhoids, varicosities, abdominal distention, and breathing difficulties. Fetal activity often is greater and more persistent as well. The following physical symptoms are indications that a mother is carrying more than one fetus and is in need of immediate follow-up examinations and laboratory evaluations: To be safe, it is prudent to consider all pregnancies as potentially multiple until it can be proven otherwise. By doing so, 75% of multifetal pregnancies can be identified before the second trimester by physical examination alone.

Definitions

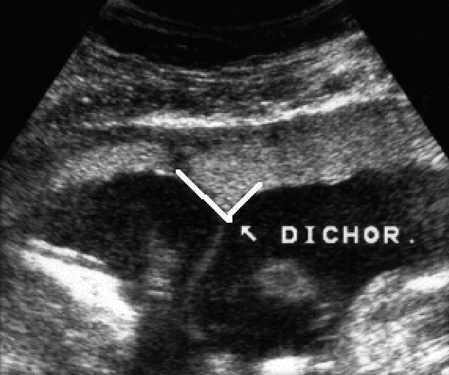

Diagnosis

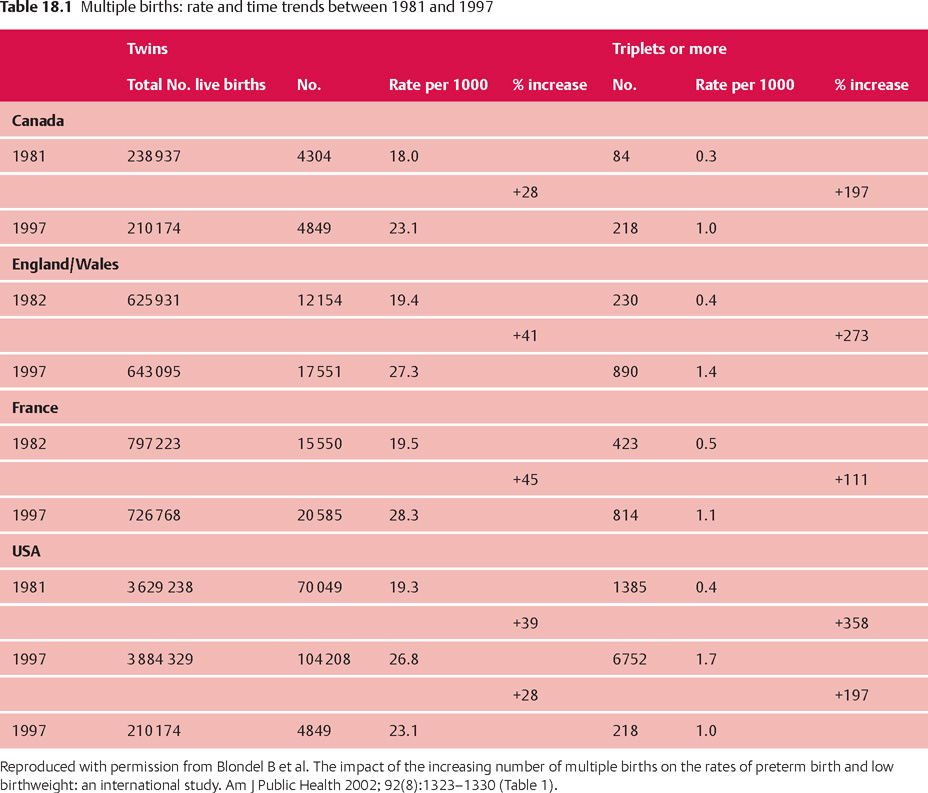

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Etiology

Pathophysiology

Mother

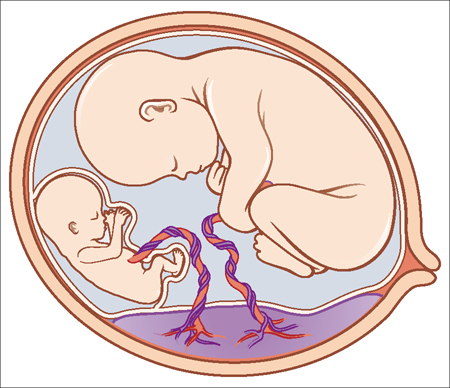

Fetus

History

Chief Symptoms

Physical Examination

Ultrasonography

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree