Microsporidiosis

Luis F. Barroso II and Richard L. Guerrant

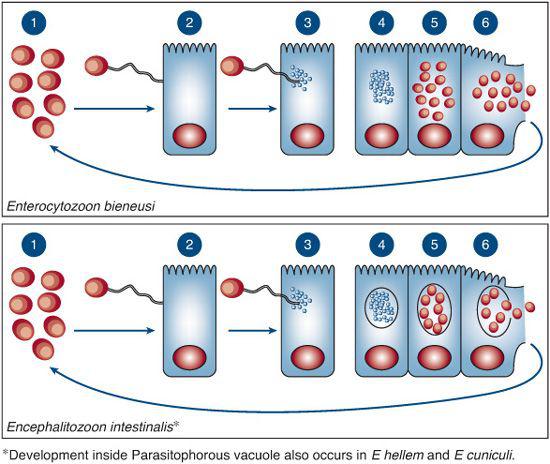

Microsporidia is a nontaxonomic term referring to an extensive group of unicellular organisms classified in the phylum Microspora. Previously considered to be primitive protists, they have been reclassified as fungi.1 All microsporidia lack mitochondria, are obligate intracellular parasites, and possess a characteristic coiled extrusion apparatus consisting of a polar tubule anchored to an anterior disk within the spore. This apparatus is capable, upon extrusion, of penetrating the host cell membrane and injecting the infectious sporoplasm material into the cytoplasm where the life cycle begins (Fig. 302-1). Of over 1200 species known, at least 14 species of microsporidia have been described that are capable of infecting humans (Table 302-1).2 The pattern of infection varies depending on the species of microsporidia and the immune status of the host.

Controversy existed as to the pathogenic potential of microsporidia in humans, since the organisms were frequently isolated from both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients. The AIDS epidemic, however, demonstrated that microsporidia are indeed pathologic agents, resulting in the discovery of 5 new species infecting humans. The propensity to cause disease versus an asymptomatic infection likely involves interplay between the immune status of the host and the species of microsporidia involved. Immunocompetent hosts may develop transient diarrhea and then become asymptomatic before the organism is eradicated, whereas severely immuno-compromised hosts may develop a wide range of clinical manifestations.3

Microsporidia are ubiquitous with an extremely broad host range, infecting nearly every animal phylum and even some protists.2 The incidence, reservoirs, and sources of infection are not well defined. Microsporidia that infect humans have been found in domestic animals, making zoonotic transmission a possibility, although very few documented zoonotic cases exist.4 The incidence of disease is higher in the tropics, as noted by seroprevalence studies and increased seroconversion with travel to tropical areas.5,6 Immunosup-pressed patients may be persistently infected.

Spores may be found in environmental water sources, and thus waterborne transmission likely plays a role in disease.7,8 Spores are relatively environmentally resistant and remain infectious for long periods of time8; however, they are inactivated through chlorination and ozonation, making them a less severe public health threat than Cryptosporidium.9,10

Microsporidial organisms are released into the environment from stool, urine, and respiratory secretions. Studies that show increased rates of coinfection with the same species of microsporidia among cohabitating men who have sex with men are evidence of person-to-person transmission11; furthermore, an outbreak of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in an orphanage is thought to have resulted from person-to-person transmission.12 The oral route is the likely mode of entry for most microsporidia infections, particularly Enterocytozoon bieneusi which is almost exclusively found in the gastrointestinal tract. An aerosol route is speculated for bronchopulmonary infections with species rarely found in stools, such as Encephalitozoon hellem. Direct inoculation into the conjunctiva is postulated to be the source of ocular infections. There is histo-pathological evidence of invasion of some microsporidia, such as Encephalitozoon intestinalis, into macrophages and fibroblasts of the lamina propria, and some species have been known to cause disseminated disease in immunocompromised hosts.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Gastrointestinal disease is the most common manifestation of infection with microsporidia; however, dissemination can occur depending on the species involved and the immune status of the host. A broad range of clinical manifestations of microsporidiosis have been reported, with infections of practically every organ system, including the hepatobiliary system,13-15 the eyes,15-18 sinuses,15,18,19 lung,15,19-21 muscles,22,23 tubulointerstitial nephritis/urinary tract,18,24,25 cardiac system,23-25 and central nervous system (Table 302-1).15,18,24,25

Microsporidia, particularly Enterocytozoon bieneusi and Encephalitozoon intestinalis, cause a diarrheal illness that ranges from asymptomatic or self-limited in immunocompetent hosts to severe and chronic in immunocom-promised hosts. Encephalitozoon cuniculi has been known to disseminate and cause central nervous system infections.18 Keratitis and corneal ulcerations have been reported with Nosema ocularum, Vittaforma corneae, as well as other microsporidia.16,18Pleistophora species have been found in patients with myositis. Disseminated infection has been reported with N connori.

Up to 50% of chronic diarrhea cases of undetermined etiology in HIV-infected patients are caused by microsporidia, in particular Enterocytozoon bieneusi and Encephalitozoon intestinalis26-29; although prevalence data vary considerably depending on the population and region studied. Infection usually occurs in the setting of young adults with advanced AIDS (CD4 count < 50/mm3), but severely immunocompromised children may also be affected. The disease typically presents with afebrile, nonbloody, watery diarrhea with up to 20 bowel movements per day. The diarrhea is exacerbated by food intake and associated with progressive weight loss, anorexia, and malabsorption. Children may present with failure to thrive, intermittent abdominal pain, and chronic diarrhea.

Enterocytozoon bieneusi invades enterocytes, producing a limited inflammatory reaction with abnormalities of the villi but rarely invades the lamina propria and thus causes only gastrointestinal disease.2,30 Dissemination outside of the gastrointestinal tract is rare. Encephalitozoon intestinalis, on the other hand, has a higher potential for dissemination. Spread to the biliary tract results in cholangitis and acalculous cholecystitis, indistinguishable from AIDS cholangiopathy caused by cytomegalo-virus and Cryptosporidium.14

Keratoconjunctivitis is associated with T hominis, and all three Encephalitozoon species and is characterized by conjunctival inflammation, photophobia, blurred vision, foreign body sensation, and decreased visual acuity. Ocular involvement may result from disseminated infection with organisms in the urine, sputum, and nasal mucosa, but it may also be isolated as a result of direct inoculation. Encephalitozoon species infections may also manifest as sinusitis with mucopurulent nasal discharge and lower respiratory tract involvement, which may be asymptomatic or associated with bronchiolitis or pneumonia.15,20,21

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree