2Edinburgh Breast Unit, Western General Hospital, Edinburgh, UK

Overview

- Approximately one third of all patients with operable breast cancer develop metastatic disease

- Metastatic breast cancer has a hugely variable natural history

- Therapy should be based on the most current information on disease extent, oestrogen receptor, progesterone receptor and HER2 receptor

- Patients who become resistant to one drug can frequently respond to second- or third-line endocrine or chemotherapeutic agents

- Supporting drugs that have direct effects on bones such as bisphosphonates or denosumab have an important role in disease that has metastasised to bone

- Symptom control is important in the terminal phase of patients with breast cancer

About one third of patients treated with curative intent will eventually develop secondary breast cancer with ultimately fatal results. A small but significant percentage of women who present with breast cancer have metastases at the time of their initial presentation. Thus at any given time there are in the United Kingdom around 100 000 women who have metastatic breast cancer, with 12 000 or so dying each year. Globally around 500 000 women die annually from breast cancer.

Few other cancers when they metastasise have such a variable natural course and effect on survival as breast cancer. Patients with hormone-sensitive cancers may live for many years without any intervention other than various sequential hormonal manipulations (Table 13.1). Also some with metastatic HER2-positive cancers who previously had a poor outlook can live many years on trastuzumab. In contrast, patients with disease that is not hormone or trastuzumab sensitive tend to have a much shorter interval free of disease and shorter survival, reflecting the more aggressive biology of most hormone-independent cancers.

Table 13.1 Endocrine drugs for breast cancer.

Anti-oestrogens

| Oestrogens

|

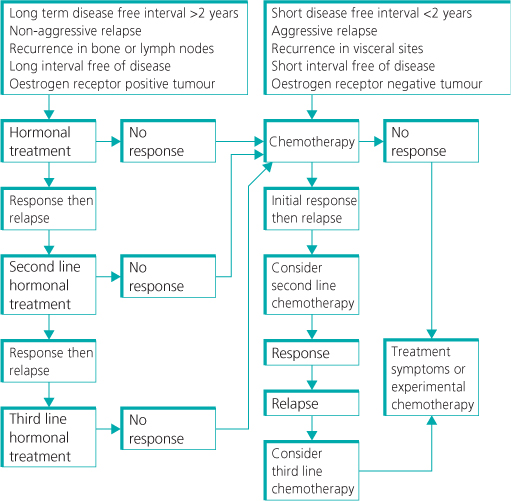

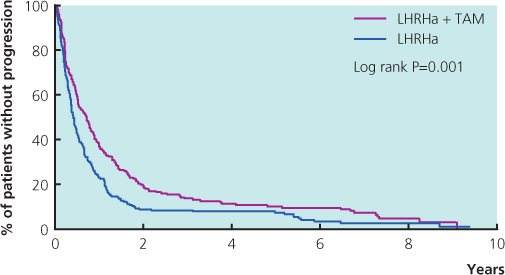

Clinical patterns of relapse predict future behaviour. There is a peak of metastatic relapses that occur within the first two years after diagnosis and treatment of localised disease. Patients with a long interval without disease (more than two years) after primary diagnosis and favourable sites of recurrence (such as local lymph nodes and chest wall) survive longer than patients with either a short interval without disease or recurrence at other sites (Figure 13.1). Patients with visceral disease have the poorest outlook; these patients tend to have a short interval between diagnosis and development of metastatic disease and a short interval free of progressive disease between systemic therapies, as these cancers are biologically more aggressive. Quoting an overall median survival of three years for metastatic breast cancer thus has little meaning for an individual patient.

Figure 13.1 Median time of survival associated with sites of metastasis in patients with breast cancer.

Treatment of Metastatic Disease

A patient may present with metastatic breast carcinoma or develop a systemic recurrence after treatment for an apparently localised breast cancer. The aim of treatment is to produce effective control of symptoms with minimal side effects and to improve survival if feasible.

Although endocrine therapy is the most widely used treatment, it is only useful in patients who have proven hormone-responsive disease or where there is clear presence of oestrogen and/or progesterone receptor in the tumour. Surrogates for hormone sensitivity may be useful, such as a long period from first diagnosis (more than two years is conventional) and non-visceral sites of involvement. However, we are now in an era when the overwhelming majority of patients should have already had immuno-histochemical profiling of the primary cancer. Biopsy of any metastatic lesion, provided that the risk of complications is small, is also valuable in planning therapy, because the hormone receptor status and even the HER2 status change in up to 30% of metastatic cancers.

Hormonal Treatment

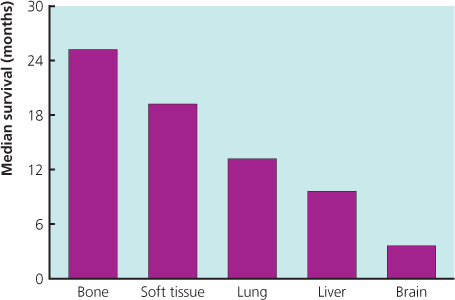

A variety of hormonal drugs is available for use in metastatic breast cancer. Objective responses to hormonal treatment are seen in 30% of all patients and in 50–60% of patients with oestrogen receptor-positive tumours (Figure 13.2(a)). Response rates of 25% are seen with second-line hormonal treatments, although less than 15% of patients who show no response to first-line hormonal treatment will respond to second-line treatment, and 10–15% respond to third-line treatment.

Figure 13.2 (a) Structures of antiaromatase drugs. (b) Patient with metastatic cancer to skin and axilla (left) showing a response to endocrine therapy (right).

Premenopausal Women

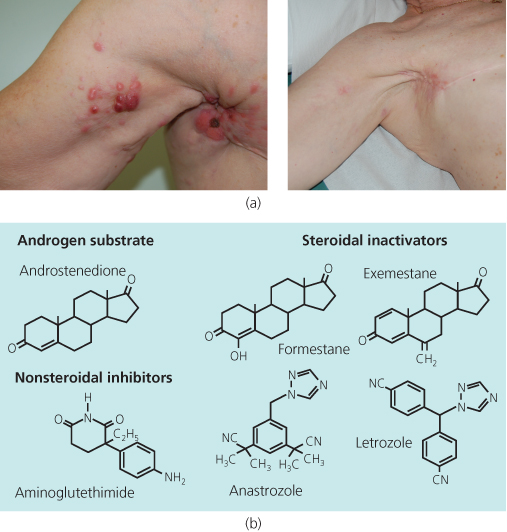

A combination of tamoxifen and goserelin is superior to either agent alone (Figure 13.3). Studies have compared this combination in the adjuvant setting. Combining goserelin and anastrozole, an aromatase inhibitor, showed no benefit compared with tamoxifen and goserelin in the adjuvant setting. There are no data on metastatic disease. Following progression on goserelin and tamoxifen switching to goserelin and an aromatase inhibitor such as letrozole is appropriate.

Figure 13.3 Meta-analysis of trials in premenopausal women with metastatic breast cancer comparing luteinising-releasing hormone analogues (LHRHa) with or without tamoxifen (TAM): progression-free survival.

Postmenopausal Women

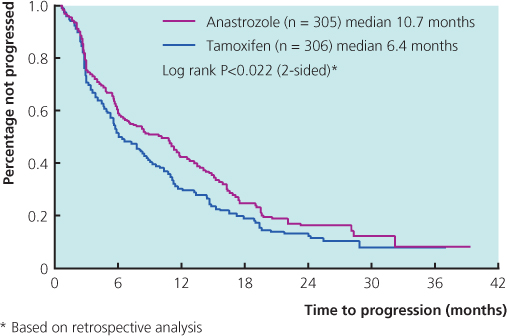

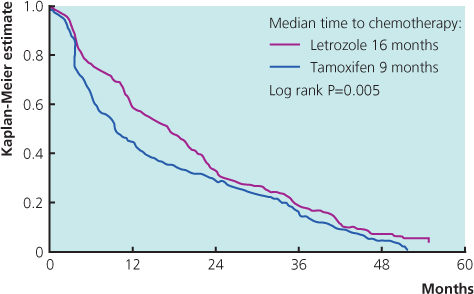

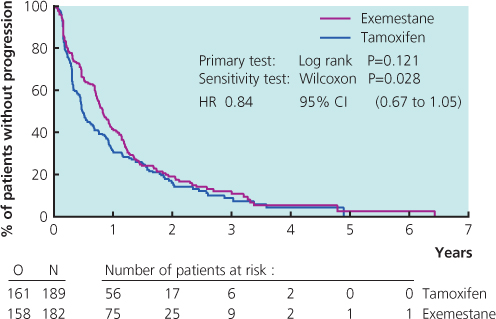

Tamoxifen used to be the most commonly prescribed drug in patients who had not received this as adjuvant treatment, but the advent of potent third-generation aromatase inhibitors has changed this (Figure 13.2(b)). Results from large randomised trials comparing tamoxifen with anastrozole or letrozole have demonstrated that aromatase inhibitors are well tolerated and have superior efficacy to tamoxifen. A combined analysis of North American and European studies comparing anastrozole versus tamoxifen in the first-line metastatic setting demonstrated a superior time to progression in patients with ER-positive breast cancer for anastrozole (Figure 13.4). A large study comparing letrozole and tamoxifen showed letrozole to be superior in all outcomes in all groups of patients (Figure 13.5), with a superior response rate of 31% versus 21%, longer time to progression and treatment failure, prolonged time to chemotherapy and a significantly better survival profile in the first two years. Data comparing exemestane and tamoxifen show superiority for exemestane in most outcomes, but no difference in survival (Figure 13.6). Letrozole or anastrozole is the agent of choice for patients with ER-positive breast cancer who have not received these agents in the adjuvant setting.

Figure 13.4 Kaplan-Meier curve of time to progression in patients from trials 0030 and 0027 who were known to have receptor-positive breast cancers. The study randomised patients to anastrozole and tamoxifen as first-line treatment in metastatic breast cancer.

Figure 13.5 Kaplan-Meier curve of time to chemotherapy in the first-line randomised study of letrozole v. tamoxifen in patients with metastatic breast cancer. From Mouridsen et al. (2003).

Figure 13.6 Kaplan-Meier curve for time to treatment progression from the phase II randomised trial of first-line hormonal treatment with exemestane or tamoxifen in postmenopausal women with metastatic breast cancer. Presented at ASCO 2004.

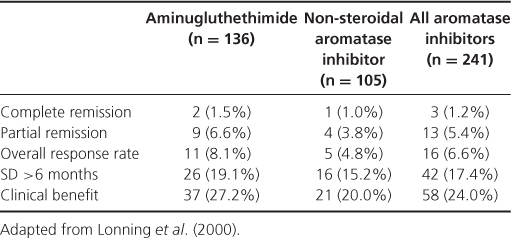

After failure of the non-steroidal aromatase inhibitors letrozole or anastrozole, the choice of agents includes tamoxifen, if not used previously, or exemestane, a steroidal aromatase inactivator (Table 13.2), and the anti-oestrogen fulvestrant. Having a novel mechanism of action, the antioestrogen fulvestrant downregulates ER expression. Given as an intramuscular injection at a dose of 250 mg once a month, fulvestrant was compared with anastrozole in the second-line setting and with tamoxifen as first line. Fulvestrant was as effective as anastrozole at this dose and was as effective as tamoxifen in patients with ER-positive cancer. Given in a dose of 500 mg, fulvestrant appears more effective than anastrozole. Time to progression with fulvestrant 500 mg was increased to 23.4 months compared with 13.1 months for anastrozole, p = 0.01, HR 0.66 (0.47–0.92) (Table 13.3). The progestagens, megestrol acetate and medroxyprogesterone are still occasionally used as third- or fourth-line agents. They are effective, but have been superseded by newer agents with a better side-effect profile.

Table 13.2 Response to exemestane after failure of second-line aromatase inhibitors.

Table 13.3 FIRST: Fulvestrant significantly increased TTP in secondary analysis.

| Parameter | Fulvestrant (n = 102) | Anastrozole (n = 103) |

| Patients progressing, n (%) | 63 (61.8) | 79 (76.7) |

| Median TTP, mos | 23.4 | 13.1 |

| HR (95% Cl) | 0.66 (0.47–0.92); P = .01 | |

After cells develop resistance to anti-oestrogens and oestrogen withdrawal they become very sensitive to oestrogen. This observation has led to renewed interest in using pharmacological doses of oestrogen. Patients can develop an initial flare with these agents and can have an increase in bone pain if metastases are present, but impressive and long-lasting responses are seen in some patients.

Chemotherapy

With chemotherapy, a balance must be achieved between a high rate of response and limiting the side effects. In randomised trials more active regimens have been shown to improve survival. The best palliation is also usually obtained with regimens that produce the highest response rates. Overall rates of response to chemotherapy are about 40–60%, with a median time to relapse of six to ten months. Subsequent courses of chemotherapy have lower rates of response of less than 25% (Figure 13.7). The chemotherapy regimens used for metastatic breast cancer are similar to those used for adjuvant and primary systemic treatment. The main reason for considering agents such as epirubicin and mitoxantrone is a greater safety margin for the cardiotoxic effect that results from continued anthracycline exposure.

Which Cytotoxics are Effective?

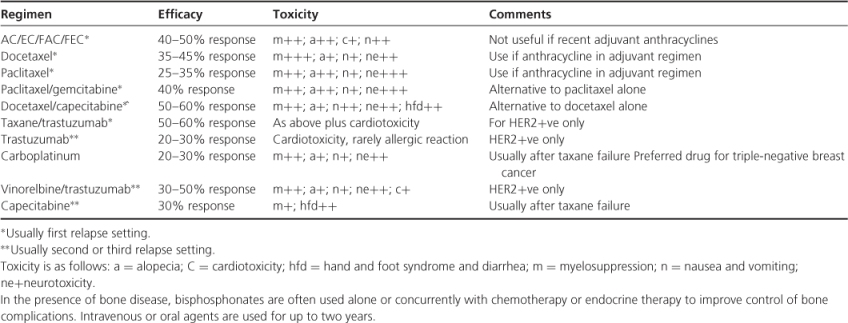

A variety of agents are effective and active in the treatment of metastatic breast cancer (Table 13.4). Anthracyclines may be considered even after adjuvant therapy exposure if the disease-free interval is 12 months or more.Taxanes are effective in anthracycline-resistant disease, with a response rate of between 30% and 40%, and are the most commonly used agents following relapse in women exposed to anthracyclines used either in metastatic disease or in the adjuvant setting. The activity of three-weekly docetaxel is higher than that of three-weekly paclitaxel, but side effects and morbidity are much greater with docetaxel. Giving paclitaxel weekly increases its efficacy and at the same time reduces side effects.

Table 13.4 Common regimens for metastatic breast cancer.

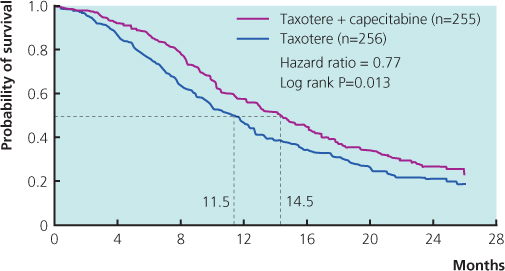

The orally active fluoropyrimidine, capecitabine, mimics the pharmacology of continuously infused intravenous 5-fluorouracil (Figure 13.8). Most oncologists now use capecitabine at some point in the management of metastatic disease. It is active with response rates of 30–40%, usually well tolerated, given by mouth twice daily and is not significantly myelotoxic. It also does not cause hair loss. Routinely, it is given at doses 20–30% below the labelled dose and this seems to allow prolonged, tolerable and effective treatment. The vinca alkaloid, vinorelbine, is well tolerated but has limited activity as a third-line therapy, either alone or in combination.

Figure 13.8 Overall survival of patients with metastatic breast cancer randomised to receive taxotere alone or a combination of capecitabine and taxotere. From O’Shaughnessy et al. (2002).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree