enopausal woman, the risk of a neoplasm being malignant is 7% to 13%, while it is 30% to 45% in the postmenopausal woman.

For the young woman in her teens and up to mid 20s, the majority of ovarian cysts are benign. Hemorrhagic corpora

lutea and follicular cysts are common. In this age range, however, tubal abnormalities should be strongly considered. They include ectopic pregnancies and sequelae from tubal infections. Endometriomas and myomas (Fig. 62.1) will also start to appear, and most of the neoplasms are benign dermoid cysts. The solid mass is of concern in this age group. The germ cell tumors, which for the most part are solid and unilateral, occur rarely but almost exclusively in this population.

lutea and follicular cysts are common. In this age range, however, tubal abnormalities should be strongly considered. They include ectopic pregnancies and sequelae from tubal infections. Endometriomas and myomas (Fig. 62.1) will also start to appear, and most of the neoplasms are benign dermoid cysts. The solid mass is of concern in this age group. The germ cell tumors, which for the most part are solid and unilateral, occur rarely but almost exclusively in this population.

TABLE 62.1 Masses Occurring in the Adnexal Region | |

|---|---|

|

In the older yet still reproductive age group, benign masses still prevail. Again, the functional ovarian cysts are still common, and endometriomas and myomas remain high in the differential. Most neoplasms are still benign, with dermoid cysts and serous cystadenomas topping the list. Lastly, there is most concern for the postmenopausal group. While most masses are still benign, there is a big jump in the risk of malignant neoplasms with epithelial ovarian cancers prevailing.

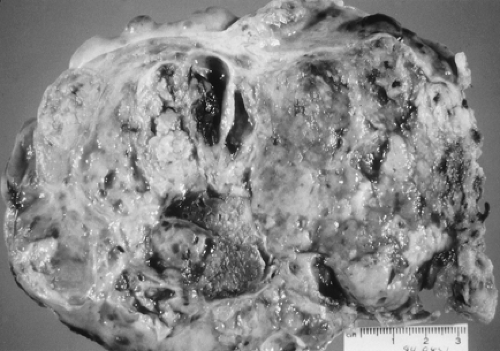

Figure 62.1 Large subserosal uterine leiomyoma. (See Color Plate) |

Review of Adnexal Pathology

Non-neoplastic Cysts

Physiologic cysts can appear as adnexal massvarian neoplasm. Their invasive counterpart, the mucinous cystadenocarcinoma (Fig. 62.2), represents 15% of invasive ovarian epithelial cancers.

Endometrioid Tumors, Benign and Malignant

The third epithelial type is the endometrioid neoplasm. These tumors recapitulate the endometrium, and thus the epithelial component resembles the endometrial glandular cell. Benign tumors of this histologic type are less common and are associated histologically with changes of adenofibroma or cystadenofibroma. The endometrioid malignant ovarian neopolasm represents up to 25% of ovarian epithelial cancers and usually is moderate in size, ranging up to 20 cm. Most ovarian endometrioid neoplasms are malignant. The malignant form tends to be bilateral in 30% of cases. When an endometrioid ovarian invasive cancer is found, up to 25% of patients will have concomitant uterine endometrial cancer or hyperplasia. Pelvic endometriosis may also be found, and one hypothesis is that these lesions arise from preexisting endometriosis. When an endometrioid invasive cancer is found in the ovary, the pathologist should indicate if it is primary to the ovary or a metastasis from a primary uterine cancer.

of the following types: serous, mucinous, endometrioid, clear cell, and transitional cell.

Serous Tumors, Benign and Malignant

Serous tumors are the most common histologic type, and the benign counterpart accounts for 50% to 70% of all benign ovarian neoplasms. Although a patient of any age can manifest a benign serous tumor, the average age is 40 years. On ultrasonographic evaluation, these cysts range from simple cysts to cysts with some complexity characterized by the presence of internal echos and septations. They can be large and are bilateral in 20% of cases.

The invasive serous ovarian carcinoma is the prototype for invasive ovarian cancers and accounts for approximately 50% of all ovarian cancers. It usually occurs in the menopause and frequently is bilateral. As with most epithelial ovarian cancers, the tumors are typically widely disseminated at the time of diagnosis.

Mucinous Tumors, Benign and Malignant

Benign mucinous tumors, or mucinous cystadenomas, account for 25% of all benign ovarian neoplasms. They occur at a slightly younger age than serous benign tumors and can occur in young women as well. They are rarely bilateral, with both ovaries involved in only 3% of cases. Mucinous tumors tend to be very large and can be multiloculated. These are the tumors that have been reported to weigh up to 100 kg. Histologically, the cells are mucin filled and show endocervical or intestinal differentiation. These are the second most common type of ovarian neoplasm. Their invasive counterpart, the mucinous cystadenocarcinoma (Fig. 62.2), represents 15% of invasive ovarian epithelial cancers.

Endometrioid Tumors, Benign and Malignant

The third epithelial type is the endometrioid neoplasm. These tumors recapitulate the endometrium, and thus the epithelial component resembles the endometrial glandular cell. Benign tumors of this histologic type are less common and are associated histologically with changes of adenofibroma or cystadenofibroma. The endometrioid malignant ovarian neopolasm represents up to 25% of ovarian epithelial cancers and usually is moderate in size, ranging up to 20 cm. Most ovarian endometrioid neoplasms are malignant. The malignant form tends to be bilateral in 30% of cases. When an endometrioid ovarian invasive cancer is found, up to 25% of patients will have concomitant uterine endometrial cancer or hyperplasia. Pelvic endometriosis may also be found, and one hypothesis is that these lesions arise from preexisting endometriosis. When an endometrioid invasive cancer is found in the ovary, the pathologist should indicate if it is primary to the ovary or a metastasis from a primary uterine cancer.

Clear Cell Tumors

The fourth general category of epithelial ovarian neoplasms is the clear cell tumor. Benign clear cell tumors are rarely diagnosed. However, the invasive clear cell carcinoma represents 10% of all ovarian cancers. The clear cell component usually coexists with another epithelial type. The clear cell histology also is associated with endometriosis elsewhere in the pelvis in up to 25% of cases.

Transitional Cell Tumors

Lastly, transitional cell tumors, which mimic the epithelium found in the bladder, are rare. The Brenner tumor is a well-known transitional cell tumor and accounts for 2% of all ovarian epithelial tumors. Brenner tumors are usually benign, although a malignant variant does exist.

Germ Cell Tumors, Benign and Malignant

The dermoid cyst is a common benign tumor found in all ages. This tumor, also known as a teratoma, is comprised of three germ cell layers: the ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm. It accounts for 25% of all ovarian neoplasms, is bilateral in up to 15% of cases, and is most commonly found in the reproductive age group. The mature teratoma can grow to quite a large size before a patient has pain or notices abdominal swelling. These tumors are well known for their smooth, glistening, pearly white surface. Either cystectomy, preferable in the reproductive-age woman, or adnexectomy can be performed to treat this neoplasm effectively. These tumors are interesting because of the granulosa cell tumor, long-term outcome is linked to stage and tumor grade.

Metastatic Tumors

Approximately 3% to 5% of ovarian malignancies aell known for the greasy sebaceous material associated with hair, bone, or teeth found within the cyst. Thyroid tissue, salivary gland tissue, and gastrointestinal and bronchial epithelium can be found. Other ectodermal tissues, including brain, neural, retina, and choroids plexus, are also found. Clinical complications associated with the

presence of these neopolasms include torsion, rupture, and infection. More uncommonly, hemolytic anemia and malignant transformation (especially of the squamous components) may also occur.

presence of these neopolasms include torsion, rupture, and infection. More uncommonly, hemolytic anemia and malignant transformation (especially of the squamous components) may also occur.

Malignant germ cell tumors account for approximately 6% of all ovarian malignancies. The most common is a dysgerminoma (Fig. 62.3). This is also the most common ovarian malignancy for young and pregnant women. This germ cell tumor is unusual in that it has a high incidence of bilaterality. If a solid tumor is found and a germ cell tumor is suspected, appropriate tumor markers as noted below may be obtained. However, none of these markers is necessarily predictive of finding a germ cell tumor. Less common germ cell tumors are the endodermal sinus tumor, classically associated with elevated α-fetoprotein (AFP), and, carrying a worse prognosis, the malignant or immature teratoma and mixed germ cell tumors, among others.

Stromal Tumors, Benign and Malignant

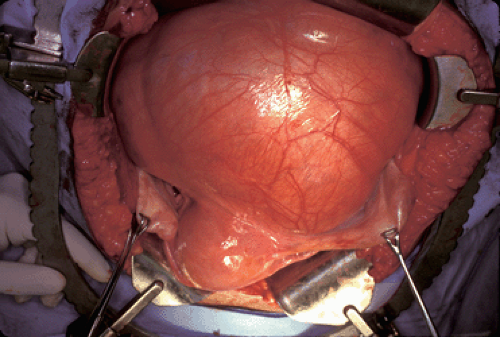

The sex cord–stromal tumors (SCST) account for approximately 10% of all ovarian tumors and 5% of malignant ovarian tumors. As a category, these tumors can occur at any age, from prepubertal to postmenopausal. Most of the hormonally active tumors fall in this category. Because of this, with the exception of the inert fibroma, they are frequently associated with endometrial pathology or other evidence of estrogen or androgen excess. The prototype benign tumors are in the thecoma–fibroma group (Fig. 62.4). Ascites and pleural effusion, or Meigs syndrome, can be found with very large fibromas due to transudation of fluid from the surface of these edematous ovaries. The most common malignant tumor is the granulosa cell tumor. This tumor classically is large and hemorrhagic and as a result can cause pain. Long-term outcome is good for those with stage I disease, but unfortunately, survival is poor with advanced disease or recurrence. Another notable malignancy is the rare Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor, classically associated with androgen excess. Similar toome complex. In addition to the abnormal findings noted previously for which surgery is recommended, growth of a mass, development of complex characteristics in any age group, or development of concerning symptoms is most likely an indication for surgical evaluation. Otherwise, the stable, asymptomatic simple cyst can be followed. In addition to ultrasonographic morphology findings, Doppler sonography may add some information. Doppler ultrasonography allows an evaluation of ovarian blood flow. With emission of a sound wave from a stationary source, reflection ofresent as bilateral pelvic masses and may be associated with other stigmata of metastatic disease.

Radiologic Evaluation of the Adnexal Mass

Whether suspicion of an adnexal mass arises as a result of a patient’s symptoms or suspicious findings during a pelvic examination, radiologic imaging is usually the next step in the diagnostic evaluation. For gynecologic problems, transvaginal ultrasonography gives the best visualization of the adnexal region by c=”http://ovidsp.tx.ovid.com/FullTextService/CT{06b9ee1beed5941925924a30f39f86ed5aa50e4b66334a534e22b517ade8c6d9ce8d3e6e03c965e1b1a7887d9b825ec3}/C62FF5.gif?geom=500×500″>

Figure 62.5 Ultrasonographic image of an ovary with internal wall papillations. The final pathologn size, thick and numerous septae, or internal papillations or nodular structures. Masses with any of these characteristics should not be observed further, and surgical evaluation would be in order (Fig. 62.5). The presence of a small volume of free fluid can be physiologic, but large volumes are ominous and suggest either a malignancy or serious medical condition. Other important features found on ultrasonography actually can be reassuring, such as calcium found next to fat, as noted in dermoid tumors. Morphology indexing has been developed to assess the malignant potential of pelvic masses by taking into consideration tumor volume and structural characteristics of the mass. On these scales, a low score is highly predictive of a benign process, while an elevated score is suggestive of a malignancy.

An ultrasonographic evaluation can help to clarify the etiology of the mass. Although not definitive, suggestions that the mass may arise from the tube, as in the case of a hydrosalpinx or tuboovarian abscess, can be helpful. Particularly troublesome are endometriomas and hemorrhagic ovarian cysts, as these can have characteristics that mimic ovarian malignancies. These are operator dependent, and as such, it is helpful to have a skilled ultrasonographer in these settings.

Simple cysts, regardless of size and patient age, are almost always benign. Data from screening studies and autopsy series suggests that the incidence of ovarian cysts in postmenopausal women is between 3% and 18%. If unilocular and <10 cm in size, the risk of malignancy is 0.1%. If these cysts are followed, 50% to 70% will resolve while one third will persist or bectrue;” onmouseout=”window.status=”; return true;”>Fig. 62.6

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree