Management of Soft-Tissue Injuries of the Mouth

Magdy W. Attia

John Loiselle

Introduction

The physician who deals with the pediatric age group is frequently called on to evaluate oral trauma (1,2). Children often present to the emergency department (ED) after apparently minor trauma with fractured teeth or lacerations to the oral soft tissues.

Blunt trauma is the most common source of orofacial injuries in children and is usually the result of striking the mouth on a piece of furniture or from a fall. In the younger age groups, the possibility of child abuse should always be considered (3). Animal bites are another frequent cause. Children are at greater risk than adults for being the victim of an animal bite. Three fourths of all bites involve the extremities; however, because of their small size, children are more likely to suffer bites to the face. Bites to the lips are particularly common, sustained while “kissing” an animal (4).

Electrical burns of the lips and tongue are not an uncommon injury among young children, who are predisposed to mouthing electrical outlets and cords. It is important to elicit an adequate history relative to the nature of the trauma, because these scenarios will differ in pattern and extent of injury (5).

Closure of oral mucosal lacerations will result in decreased healing time, decreased propensity for infection, and adequate hemostasis and cosmesis (5,6,7). The issue of cosmesis is one of utmost importance for the parent and patient, particularly if there is an injury involving the lips.

The complexity of injuries varies greatly. The majority heal well without intervention. Those that require repair can, in most cases, be handled by any experienced physician. A small number require surgical expertise. It is imperative to rule out associated injuries, but most facial lacerations are simple and are easily managed by ED personnel. Occasionally, other medical priorities necessitate deferring treatment to the inpatient setting. Extensive facial lacerations are preferably closed by a specialist in the operating room. Consultants may include a general, plastic, or oral surgeon; a dentist; or an otorhinolaryngologist.

Anatomy and Physiology

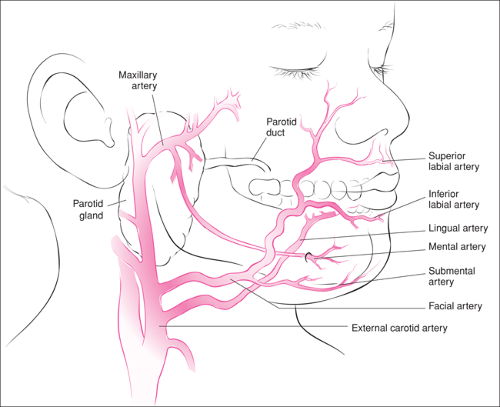

The generous blood flow to the face and mouth contributes to its excellent healing potential (Fig. 67.1). The upper lip is supplied by the superior labial arteries, which branch from the facial arteries. The lower lip also is supplied by branches of the facial artery known as the “inferior labial arteries.” The labial arteries join to form a ring about the mouth. The inferior labial arteries have anastomoses with the mental and submental arteries, which are branches of the maxillary and facial arteries, respectively.

The tongue receives its main blood supply from the lingual arteries (Fig. 67.1). Branches of the lingual artery and the inferior alveolar artery provide blood supply to the mucosa of the floor of the mouth. The maxillary and palatal mucosa are supplied by branches of the maxillary arteries. The buccal mucosa is supplied by branches of both the facial and maxillary arteries (8).

The nerve supply to the area is equally complex and is mostly derived from the trigeminal and glossopharyngeal nerves (see Fig. 62.1).

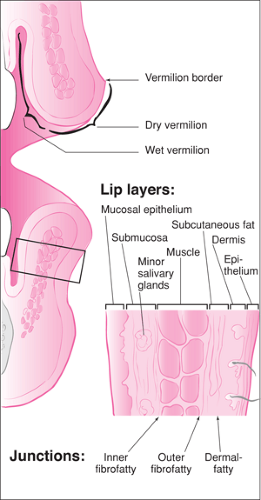

The structure of a lip is multilayered, as shown in Figure 67.2. The skin comprises the external layer and the mucosa the internal layer. The middle layer is composed of muscle (the orbicularis oris), which encircles the mouth. A fibrofatty

junction borders both the inside and the outside surfaces of the muscle. Between the inner fibrofatty junction and the mucosa, a layer of submucosal or minor salivary glands is present.

junction borders both the inside and the outside surfaces of the muscle. Between the inner fibrofatty junction and the mucosa, a layer of submucosal or minor salivary glands is present.

The vermilion border is the mucocutaneous junction of the lips where the mucosa meets the skin. A common lip injury treated in the ED is a through-and-through laceration. These lacerations often involve the vermilion border, which is a fixed and obvious landmark.

The tongue is composed almost entirely of eight separate muscle groups, which confer a wide variation of movement. It is covered on the dorsal and inferior surfaces by mucous membrane. The anterior two thirds of the dorsal surface contains the numerous papillae or taste buds.

When a child mouths an electrical outlet or two bared wires, saliva will complete the arc. A spark burn will result. Fortunately, the immediate reaction of the victim is to jerk away. When a child bites into a cord, current courses through the soft tissue and produces a muscle contraction. The victim is unable to release the cord because of the ongoing perioral muscle contraction, and the burn progresses (5).

Spark burns produce a limited white blister and will not result in much deep tissue necrosis. Current burns are more diffuse. Necrosis of deep tissues will occur, and the eschar will break down approximately 5 to 10 days postinjury. Without vital connective tissue support, damaged circumoral vessels also will necrose, tear, and bleed (5,9). Although this is a rare scenario, parents should be alerted to the possibility of delayed bleeding and the need to seek medical attention at the first indication of bleeding (10). Pain and edema may prevent adequate oral hydration or, in more severe cases, result in airway compromise.

The parotid duct is an additional structure within the mouth that may be injured. It originates at the anterior parotid gland and courses anteriorly. The duct turns medially at the anterior border of the masseter muscle and penetrates the buccinator muscle. It then courses obliquely forward to exit

the mucosa at Stensen’s papillae opposite the maxillary second molar (8).

the mucosa at Stensen’s papillae opposite the maxillary second molar (8).

Indications

The generous blood supply of the face and mouth allows the vast majority of intraoral lacerations to heal well on their own. This benefit is counterbalanced by the fact that even the smallest lacerations in the facial area can leave cosmetically disfiguring scars. The elapsed time from wound occurrence and the degree of contamination of wound are additional concerns for infection. These issues must be considered when deciding on the need for primary closure.

A few general recommendations can be made regarding closure of lip lacerations. Lacerations that are greater than approximately 2 cm, especially when they occur on the dry mucosa, will heal more rapidly and with less distress to the patient if sutured. All lacerations involving the vermilion border should be closed. Through-and-through lacerations of the lip will also require layered suture repair.

The tongue also is composed of highly vascularized tissue, and hemostasis may be an issue in the decision to close a tongue laceration, although bleeding often stops spontaneously. Full thickness lacerations should, in most cases, be repaired. Lacerations that result in a division of a free edge of the tongue have the potential to heal with a persistent cleft and therefore require closure. In addition, tongue lacerations that are large enough to entrap food particles heal more slowly and should be sutured.

Through-and-through lacerations of the oral mucosa should be closed. Lacerations that result in a flap may require suture repair if they are at risk for further trauma from biting. Hemostasis also may be an issue in these injuries. Lacerations producing communication between the oral cavity and nasal passages or sinuses require referral to an otolaryngologist or oral surgeon.

Injury to the Stensen duct should be suspected with any laceration crossing the middle third of a line drawn from the tragus to the central portion of the upper lip or if paralysis of the buccal branch of the facial nerve is present. Flow of irrigant into a wound from a 22-gauge intravenous catheter that is cannulating Stenson’s papillae confirms parotid duct injury. Such lacerations should be referred for definitive treatment to avoid adverse postinjury sequelae (11). Burn injuries of the mouth should not be excised, nor should primary repair be attempted. Involvement of the labial commissure necessitates referral to a specialist who can fabricate a dental appliance to stent the commissure and prevent contracture.

Tear wounds from animal bites about the face and mouth, like any other laceration, can be closed following thorough wound cleansing, irrigation, and débridement of devitalized tissue (12). True puncture wounds should not be closed but be allowed to granulate. Because of the rich vascular supply to the face and mouth, human bite wounds to this region treated within 24 hours of injury may be closed primarily. This is unlike human bites to other regions of the body, which are not closed and allowed to granulate. If more than 24 hours has elapsed since the injury, delayed primary closure of facial bite wounds is performed after resolution of infection.

Equipment

Dental anesthetic syringe or 5-mL Luer-Lok syringe

25-gauge or smaller, 1.5-inch needle

Yankauer and Frazier suction catheters

1% or 2% lidocaine with or without 1:100,000 epinephrine

Gauze sponges

Bite block

Suture tray (fine scissors, needle holder, nontraumatic forceps)

Saline for irrigation

20-mL irrigation syringe

Splash shield or 18-gauge intravenous catheter tip

Resorbable sutures 3.0, 4.0, and 5.0 chromic gut, Vicryl, Dexon

Nonresorbable sutures 5.0 and 6.0 nylon, Ethilon, Prolene

Procedure

The approach to these injuries, as with all trauma, is to initially assess for concurrent life-threatening injuries to the airway, cervical spine, or brain. Once any such injuries have been stabilized, a regional head and neck examination should evaluate for signs and symptoms of facial bone or skull fracture, such as hemotympanum, paresthesia of the divisions of the trigeminal nerve, diplopia, cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea, cerebrospinal fluid otorrhea, trismus, malocclusion, temporomandibular joint pain, and deviation of the mandible on opening (11). Injuries to the temporomandibular joints or mandibular condyles should be suspected in patients who have sustained blows to the mental symphysis region.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree