2Edinburgh Breast Unit Western General Hospital, Edinburgh, UK

3Pathology Department, Western General Hospital, Edinburgh, UK

Overview

- The single most important factor predicting patients’ prognosis is the presence or absence of cancer in the regional nodes

- All patients with invasive cancer should have their regional node status assessed by node biopsy

- An effective method of assessing lymph node status in patients with clinically and imaging node-negative nodes is to perform a sentinel lymph node biopsy

- It has been standard care until recently to treat all patients with histologically proven involved axillary nodes by axillary node clearance or axillary radiotherapy

- New data suggest that selected patients with limited node positivity on sentinel lymph node biopsy who have whole-breast radiotherapy and adequate systemic therapy may be spared further treatment of the axilla

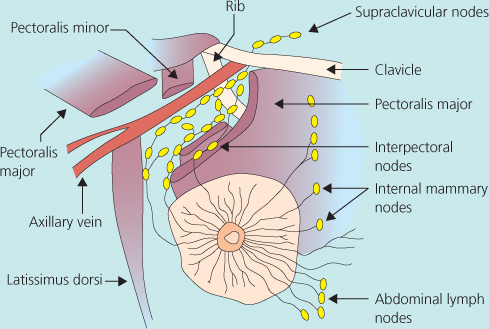

Lymph Drainage of Breast

Lymph drainage from the breast is via the axillary and internal mammary nodes (Figure 9.1). To a lesser extent, lymph also drains by intercostal routes to nodes adjacent to the vertebrae. The axillary nodes receive about 95% of the total lymph drainage, and this is reflected in the greater frequency of tumour metastases to these nodes.

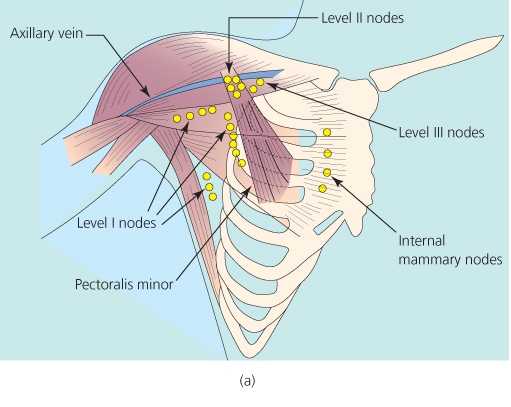

The axillary nodes, which lie below the axillary vein, can be divided into three groups in relation to the pectoralis minor muscle: level I nodes lie lateral to the muscle; level II (central) nodes lie behind the muscle; and level III (apical) nodes lie between the muscle’s medial border, the first rib, and the axillary vein (Figures 9.2 and 9.3). There are on average 20 nodes in the axilla, with about 13 nodes at level I, 5 at level II and 2 at level III. The drainage from level I nodes passes into level II nodes and on into the apical nodes. An alternative route, by which lymph can reach level III nodes without passing through nodes at level I, is through lymph nodes on the undersurface of the pectoralis major muscle, the interpectoral nodes. The orderly drainage of lymph explains why few patients with cancer have affected lymph nodes at levels II or III without involvement at level I. These so-called skip metastases are seen in less than 5% of patients with affected axillary nodes. The first node (or nodes) that received lymph drainage in the axilla or internal mammary region is known as the sentinel node or nodes. The majority of sentinel nodes are in the axilla at level I. The average number of sentinel nodes in most recent studies is between 2 and 3.

Figure 9.2 (a) Levels of axillary nodes. (b) Anatomy of the axilla split into zones A, B, C and D. Sentinel nodes are never found in zone D, but the main nodes in the axilla that drain the arm are always in zone D.

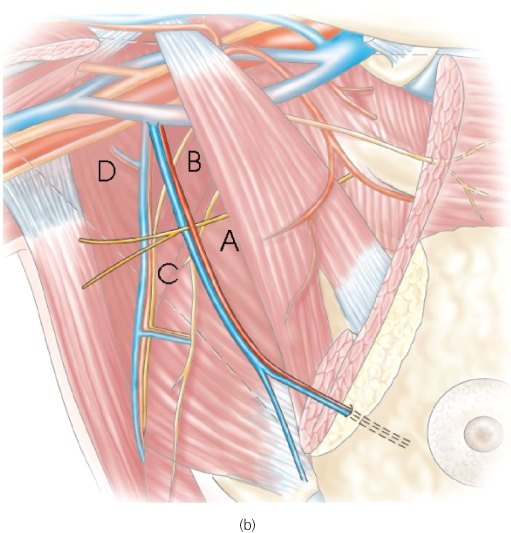

Figure 9.3 Ultrasound pictures of involved axillary nodes. All patients with invasive breast cancer should have axillary ultrasonography with fine needle aspiration cytology or core biopsy to assess whether any enlarged or abnormal node is involved. Up to half of patients with involved nodes can be detected using ultrasound guided biopsy.

Preoperative clinical or radiological assessment of lymph node involvement is not completely accurate, with only 70% of involved nodes being clinically detectable. Only histopathological assessment of nodes visualised on ultrasonography, or excised at surgery, provides accurate prognostic information. Cytology of enlarged axillary nodes visualised on ultrasound can also detect axillary node metastasis (Figure 9.3). Micrometastatic disease detected only by immunohistochemistry does not have the same implications for prognosis and management. Lymph nodes are ineffective barriers to the spread of cancer, and metastasis indicates biologically aggressive disease that requires systemic adjuvant treatment. Involvement of axillary nodes occurs in up to 40% of symptomatic breast cancers and in 20–25% of those detected by screening.

The factors that correlate with lymph node involvement in breast cancer are outlined in Table 9.1.

Table 9.1 Factors associated with lymph node involvement.

|

Identifying Patients with Involved Nodes Before Surgery

Enlarged axillary nodes can be visualised with ultrasonography (Figure 9.3). Features that indicate the node is potentially involved include thickened cortex (normal is ≤2 mm, 2–4 mm is indeterminate, >4 mm suspicious of malignancy) and distortion of architecture or increase in size. Ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) or core biopsy of visibly abnormal or enlarged nodes can identify more than half of patients with involved nodes before surgery. This can allow definitive axillary therapeutic surgery to be undertaken in patients with cytological or histological evidence of axillary lymph node involvement. Utilisation of axillary ultrasound or FNAC or core should result in less than 15% of women with sentinel lymph nodes being positive at surgery.

Role of Axillary Surgery in Patients with Operable Breast Cancer

Axillary surgery can be used to stage the axilla or to treat axillary disease, or both (Tables 9.2 and 9.3).

Table 9.2 Options for axillary surgery procedures to stage but not treat the axilla in patients with invasive breast cancer.

|

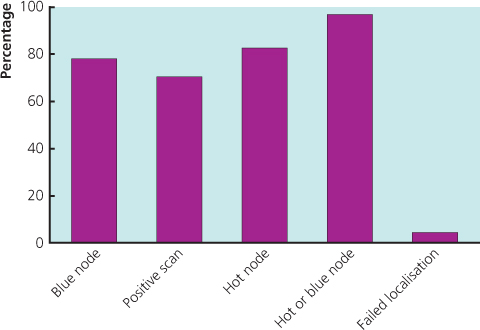

*Not recommended given evidence of the value of the combined blue dye/radioisotope technique (Figure 9.4).

Figure 9.4 Data from the validation phase of the ALMANAC sentinel node study. Each surgeon completed 40 cases and data from 840 patients were analysed. This study shows that radioisotope and blue dye are needed to achieve a satisfactory rate of sentinel lymph node detection.

Table 9.3 Procedures to treat the axilla in patients with involved axillary lymph node involvement.

|

Staging the Axilla

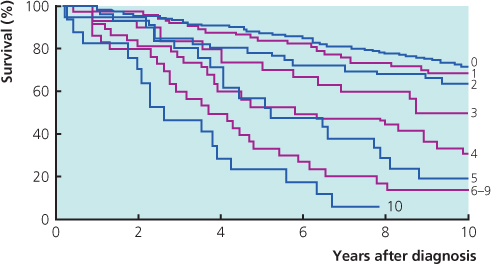

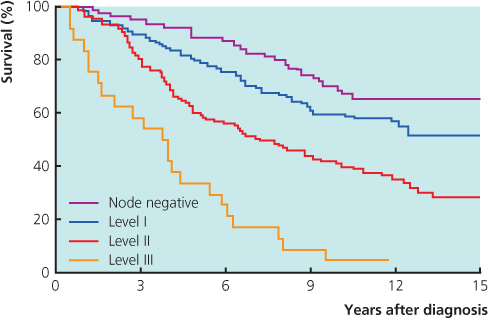

The presence or absence of involved axillary lymph nodes is the single best predictor of surviving breast cancer, and important treatment decisions are based on it (Figures 9.5 and 9.6). Both the number of involved nodes and the level of nodal involvement predict survival (Figure 9.7). Only involvement on routine histopathological examination has been shown consistently to be of prognostic importance.

Figure 9.6 Correlation between number of affected axillary lymph nodes and survival after breast cancer in patients who did not receive any systemic therapy.

Figure 9.7 Relation between level of axillary node involvement and survival after breast cancer in patients who did not receive systemic therapy. Level IV = supraclavicular node involvement.

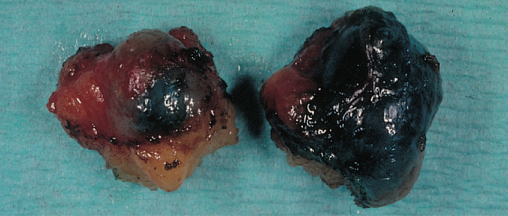

The significance of micrometastatic disease detected only by examining multiple sections of lymph nodes by immunohistochemistry is much less clear. A single non-targeted node biopsy does not adequately stage the axilla. In patients with a clinically and ultrasound-negative axilla the optimal procedure is a sentinel lymph node biopsy. Identification of the sentinel node by peritumoural, intradermal or subareolar injection of both blue dye (isosulfan blue or patent blue V) and radioisotope colloid followed by histological assessment of blue (Figures 9.4 and 9.8) and/or radioactive nodes assesses axillary node involvement with a sensitivity of at least 91% (95% CI 74–96%) and a false-negative rate of 4–10% (Figure 9.9). Subareolar injection seems to have the highest rate of sentinel node detection. In most patients there is more than one sentinel node and about 25% of all nodal metastases are not in the bluest or hottest sentinel node. The more sentinel nodes removed, the lower the false-negative rate. The average number of sentinel nodes in more recent studies is between 2 and 3, but it is important that the surgeon does not remove large numbers of sentinel nodes as this increases morbidity without affecting diagnostic utility.

Figure 9.8 Two blue sentinel axillary nodes identified after injecting patent with blue V in the subareolar region.

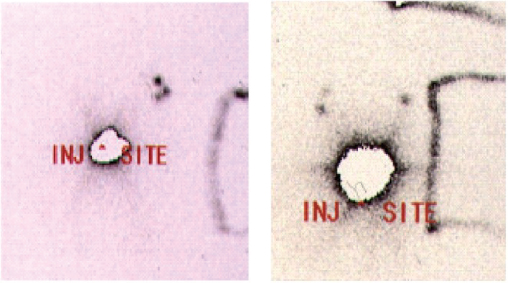

Figure 9.9 Scintiscan showing drainage of technetium 99m human albumin colloid to show both multiple sentinel axillary nodes (left) and internal mammary nodes.

Although some centres have found that sampling (surgically dissecting out four separate palpable nodes combined with blue dye alone) provides reliable information on whether axillary nodes are involved, others have found it difficult to identify and dissect out four separate axillary nodes, even with blue dye guidance. The probability of a false-negative result on sentinel node biopsy or axillary sampling decreases as the number of nodes sampled increases. Level II or III dissections (removing all nodes at levels I and II or I, II and III) provide more accurate assessments of the number and level of node involvement, but are only justified in patients with cytological or histological evidence of axillary lymph node involvement.

Some surgeons combine sentinel node biopsy with axillary lymph node sampling, removing any palpable suspicious non-sentinel nodes in an attempt to decrease the false-negative rate. The extra value of removing these extra nodes is not clear.

In some patients (range from 2–30%) injected with radioisotope colloid, scintigraphy will visualise a sentinel node in the internal mammary chain (Figure 9.9). Drainage either to more than one axillary node or to a combination of axillary and internal mammary nodes is often seen on scintigraphy. The rate of detection of isolated internal mammary sentinel node metastases is less than 1% and is seen with both medial and laterally situated cancers. Debate continues on the value of removing internal mammary nodes identified on preoperative scintigraphy. Removing internal mammary nodes is not without morbidity, as an extra incision is necessary in some patients and there is a small risk of pleural damage. Treating affected internal mammary nodes is also a problem, as these nodes are difficult to target with radiotherapy. Randomised trials of surgical excision and radiotherapy targeted at internal mammary node recurrences have not as yet shown that they improve survival and isolated mammary node recurrences are rare (Table 9.4).

Table 9.4 Current consensus on sentinel node biopsy.

|

Assessment of Sentinel Nodes

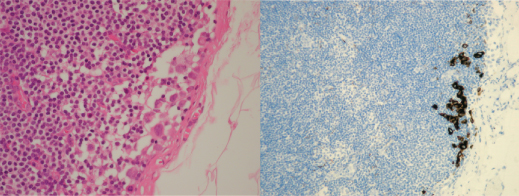

Immediate assessment of frozen sections of sentinel nodes has a false-negative rate of up to 20%. Intraoperative touch-prep cytology misses fewer metastases and has a sensitivity of over 90%; it is also quicker than frozen section. The importance of micrometastases in a sentinel node identified by serial sectioning and immunohistochemistry is not clear. Haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) detected micrometastases ≤2 mm in sentinel nodes are unlikely to be associated with spread to adjacent non-sentinel lymph nodes (Figures 9.8 and 9.10). Techniques during operation that assess whether sentinel nodes are involved using molecular techniques are available. Their utility and cost effectiveness continue to be evaluated. Although such an assessment can be carried out successfully, there are at least 3% of patients who have false-positive results, leading to unnecessary axillary node clearance, and there are no studies showing that the technique is cost effective. Results take a minimum of 20 minutes for one sentinel node and 40 minutes for two or more nodes and this can make planning of operation lists problematic. The equipment is only available in a few centres. Sentinel node biopsy is now routine for clinically and radiologically N0 tumours, particularly in patients with small tumours (≤2 cm), where the likelihood of axillary lymph involvement is low and routine axillary dissection can no longer be justified.

Figure 9.10 (a) Lymph node with isolated tumour cells—H&E and (b) immunohistochemistry by cytokeratin.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree