Management of Epistaxis

Parul B. Patel

Susanne I. Kost

Introduction

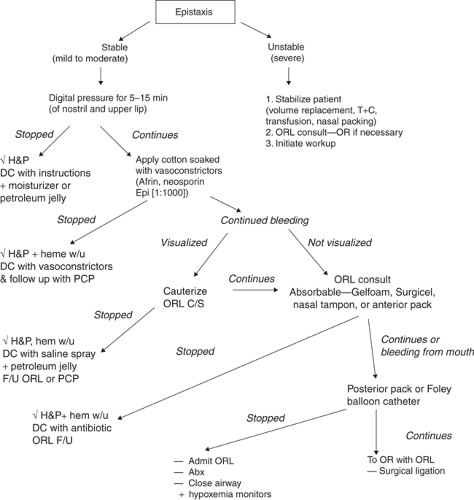

Epistaxis is a common complaint in the pediatric population, especially among toddlers and school-aged children. Most episodes of bleeding from the nose will resolve before the child arrives at a medical care facility, but persistent or recurrent bleeding requires intervention (1,2). Because specialized equipment is needed for visualization and treatment of epistaxis, a definitive procedure should not be attempted in the prehospital setting. Prehospital management of a nosebleed should consist of applying pressure to the external nares and providing supportive care as necessary. The child who is still bleeding upon arrival at a medical care facility can usually be managed by cautery or anterior packing. An emergency physician or an experienced pediatrician or family practitioner should be capable of performing both of these procedures. In the unusual situation when posterior packing is required for a pediatric patient or when epistaxis is severe or recurrent, consultation with an otolaryngologist should be obtained whenever possible (3).

Anatomy and Physiology

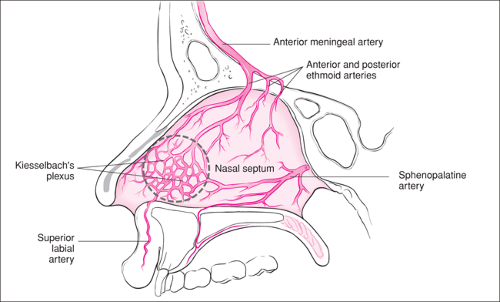

The relatively high incidence of epistaxis in otherwise healthy children can be explained by a combination of physiologic and behavioral factors. The nasal mucosa is lined with a rich vascular network that facilitates warming of inspired air. In children, this mucosa is thinner and more likely to bleed than in adults. Children also are prone to manipulate the septal mucosa (nose picking) and are therefore predisposed to anterior bleeding. The most common source of epistaxis is the Kiesselbach plexus in the Little area of the anterior septum (Fig. 57.1). Attempts to localize and treat the typical nosebleed in a child should focus on this area (1,2,4). Because blood supply to the Kiesselbach plexus comes in part from the superior labial artery, application of pressure to the upper lip may aid in the initial management.

In addition to minor trauma from nose picking, environmental, local, and systemic factors may influence the incidence of epistaxis. Environmental factors including cold air or dry heat in the winter, may irritate the mucosa, a condition known as “rhinitis sicca.” It has been shown that hospital admissions for epistaxis increase during the winter months (5). A local factor that commonly causes epistaxis in children is injury due to accidental trauma (6). Other local factors—for example, inflammation from viral or bacterial infection, foreign body reaction (see Chapter 59), allergic rhinitis, and chemical irritants (such as cigarette smoke)—may increase the friability of the anterior nasal mucosa (7,8). In adolescents, chronic inhalation of recreational drugs may lead to epistaxis. Although much less common, nasal septal deviation and lesions such as polyps, vascular malformations, and tumors may act as focal points for anterior or posterior bleeding in children (1,2,4).

Systemic conditions that may produce or exacerbate epistaxis include hypertension, hematologic disease, renal disease, menstruation, and the use of anticoagulant medication. Extensive testing for systemic illness should not be undertaken unless current or past medical history, family history, or physical examination leads to suspicion of a systemic disorder. Although hypertension is unusual in children, blood pressure should be measured routinely in a child presenting with epistaxis. Anxiety over the nosebleed and the hospital environment may cause transient hypertension; consequently, a finding of elevated systemic pressure should be confirmed with a repeat reading and then evaluated appropriately on an acute and/or outpatient basis. Hematologic disease may include congenital coagulation defects or acquired conditions such as idiopathic

thrombocytopenic purpura and malignancy (7,9). Assessing the child for bruising, petechiae, and lymphadenopathy should therefore be routinely included as part of the physical examination. An adolescent female who has episodes of epistaxis that always coincide with menstruation may have vicarious menstruation, a rare condition thought to be caused by increased capillary permeability resulting from hormonal changes. Ingestion of drugs that affect coagulation (e.g., Coumadin or aspirin) should be suspected in a setting where these drugs are available, especially in the toddler age group (1,2,10). Patients with chronic renal failure undergoing hemodialysis may present with persistent epistaxis due to coagulopathy from underlying disease or prolonged use of low-molecular-weight heparin (6).

thrombocytopenic purpura and malignancy (7,9). Assessing the child for bruising, petechiae, and lymphadenopathy should therefore be routinely included as part of the physical examination. An adolescent female who has episodes of epistaxis that always coincide with menstruation may have vicarious menstruation, a rare condition thought to be caused by increased capillary permeability resulting from hormonal changes. Ingestion of drugs that affect coagulation (e.g., Coumadin or aspirin) should be suspected in a setting where these drugs are available, especially in the toddler age group (1,2,10). Patients with chronic renal failure undergoing hemodialysis may present with persistent epistaxis due to coagulopathy from underlying disease or prolonged use of low-molecular-weight heparin (6).

Indications

Any child who continues to bleed after properly applied nasal pressure, or a child with recurrent episodes of bleeding over a period of hours or days, deserves a more definitive procedure. An adequate trial of digital nasal pressure consists of at least 5 minutes of squeezing the cartilaginous segment of the nares together between a thumb and finger. Using a rolled gauze pad to compress the upper lip (and thus the labial artery) also may be performed if the child is cooperative. If bleeding persists despite an adequate trial of pressure, vasoconstrictive medication (Afrin, Neosynephrine) may be applied to the affected area on a cotton pledget and the pressure regimen repeated. If vasoconstriction with pressure fails to control bleeding or if a presumptive source of bleeding is identified, chemical cautery should be considered. Continued epistaxis from an anterior site despite cautery requires placement of an anterior nasal pack. The persistent appearance of blood in the hypopharynx with no identifiable anterior source or after placement of an anterior nasal pack indicates a posterior site of epistaxis and necessitates placement of a posterior nasal pack (Fig. 57.2).

When the patient has a known history of an intranasal lesion (e.g., a polyp or hemangioma) or a known bleeding disorder, consultation with an otolaryngologist should be sought before attempting to cauterize or pack the affected area (7). Attempts at cauterization in a patient with a bleeding diathesis may exacerbate the bleeding. These patients may require treatment with packing and replacement of the appropriate blood product (factor or platelets). Consultation is also recommended if a posterior site of bleeding or a facial fracture is suspected. In addition, immediate consultation should be obtained in the rare instance of a severe nasal bleed resulting in unstable vital signs or signs of hemorrhagic shock (3,4,10).

Equipment

General

Adequate light source (preferably a headlight)

Suction with Frazier tip (5 to 9 French)

Nasal speculum (small, medium, large)

Cotton pledgets or swabs

Bayonet forceps

Alligator forceps

Cautery

Topical vasoconstrictors and anesthetics:

Phenylephrine 0.25% (Neosynephrine)

Oxymetazoline 0.05% (Afrin)

Lidocaine 2% to 4% (maximum dose 3 to 5 mg/kg)

Epinephrine 1:1000

Commercially premixed 2% lidocaine with epinephrine (maximum dose 5 to 7 mg/kg)

Silver nitrate sticks

Trichloroacetic acid

Petroleum or KY jelly

Anterior Packing

Vaseline gauze, ¼- and ½-inch strips

Topical antibiotic ointment

Nasal tampon (Merocel, Rapid Rhino, Rhino Rocket)

Topical absorbable hemostatic agents such as Gelfoam and Surgicel

Posterior Packing

Small red rubber or flexible latex-free catheters

Hemostat

Silk ties or umbilical tapes

Foley catheters (10 to 16 gauge)

Syringe, 30 mL

Gauze, 2″ × 2″, 4″ × 4″

Plastic cuff (2-inch length of suction tubing)

Hoffman clamp

Topical thrombin

Combined Anterior-Posterior Packing

Gottschalk Nasostat or Xomed Epistat

Procedure

Examination and Preparation

The most important task in the treatment of epistaxis is locating the site of bleeding. In an ideal situation, the patient sits upright, leaning slightly forward, and looking directly at the clinician, although with many pediatric patients, this will not be possible. An adequate light source is essential for good visualization of the nasal mucosa. A headlight provides direct illumination of the nose and frees both hands for treatment. Young or uncooperative patients may require procedural sedation before the procedures described in this section can be performed successfully (see Chapter 33). Certain patients, such as those with severe bleeding or complicated medical histories, may merit evaluation under general anesthesia in the operating room. Uncooperative or sedated patients must be positioned supine on a stretcher using appropriate restraint (e.g., a papoose), with an assistant stabilizing the head. It may be helpful to apply a topical decongestant and anesthetic to the patient’s nasal mucosa prior to the examination (see below). This can be done using sterile long cotton swabs or a spray device, depending on the formulation available.

Once the patient is calm and positioned properly, the clinician can use a nasal speculum to visualize the anterior septum. The speculum blades should be opened vertically rather than horizontally so that the septum is better visualized without being directly instrumented, thus avoiding additional pain and mucosal trauma that may result from applying pressure against the septum. Keeping the speculum blades slightly open on insertion and removal will prevent plucking nasal hairs. Clots are carefully suctioned from the nose with a Frazier tip suction catheter until the source of bleeding can be identified. If active bleeding obscures the septal mucosa, cotton pledgets soaked in a topical vasoconstrictor such as phenylephrine (Neosynephrine) or oxymetazoline (Afrin) may be inserted with bayonet forceps (Fig. 57.3). Oxymetazoline is preferred when available because it has no effect on systemic blood pressure. A success rate of 65% in the treatment of epistaxis has been reported with the use of oxymetazoline alone (6). If cautery or packing is anticipated, an anesthetic such as 4% lidocaine may be mixed with the vasoconstrictor and applied simultaneously. Phenylephrine or oxymetazoline provides vasoconstriction but not anesthesia. Either a commercially premixed preparation of lidocaine with epinephrine or a mixture prepared at the time of the procedure (0.25 mL of epinephrine 1:1000 in 20 mL of 4% lidocaine) also has been recommended. The maximum allowable dose of lidocaine alone is 3 to 5 mg/kg, and the maximum allowable dose of lidocaine with epinephrine is 5 to 7 mg/kg (11). Although total systemic absorption of lidocaine does not occur after topical administration, the maximum recommended dosages should not be exceeded. While still used by pediatric otolaryngologists, liquid cocaine, an agent that provides both vasoconstriction and anesthesia, is rarely used now for children in the emergency department because of its expense and potential for serious complications. After a topical vasoconstrictor has been properly applied for about 5 to 10 minutes, a persistent anterior source of bleeding will often be visible (3,12).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree