Management of Dental Fractures

John M. Loiselle

Melanie Pitone

Introduction

Certain tooth fractures are considered dental emergencies. Fractures can occur as the result of isolated mouth trauma or as part of multisystem injury. The severity of fractures ranges from minor cracks to complex transections of the tooth. The primary goal in the acute management of tooth fractures is to maintain the vitality of the pulp, which is the neurovascular tissue within the tooth. Viability of the tooth in many cases is time dependent, and prognosis is best when treatment is initiated shortly after the injury (1,2). Predictions of the future health of an injured tooth must be made cautiously. The extent of injury to the dental pulp is difficult to determine, and response of the pulp to injury is varied. One child may have multiple dental injuries from one incident, and each tooth may have a different outcome (3).

Three peak ages predict when pediatric dental trauma is most likely to occur. The first peak is between 1 and 3 years of age, when the child is learning to walk. Bicycle and playground injuries predominate in the 7- to 10-year-old age group. The onset of athletic endeavors and aggressive or violent activities bring the third peak, at ages 16 to 18 (4).

Patients commonly seek treatment for dental injuries in the emergency department (ED), although it is not unusual to see these injuries in the office or outpatient clinic setting. Optimal management of a tooth fracture is immediate evaluation by a dentist capable of performing a definitive restoration of the tooth. This approach should be taken when it is available. However, in considering time constraints involved with tooth viability and potential inability to obtain timely dental consultation during off hours, emergency physicians should be familiar with early management options for these injuries. Application of a protective covering (described in this chapter) and splinting (described in Chapter 66) are temporizing procedures performed before eventual aesthetic restoration of the tooth in an outpatient setting.

Anatomy and Physiology

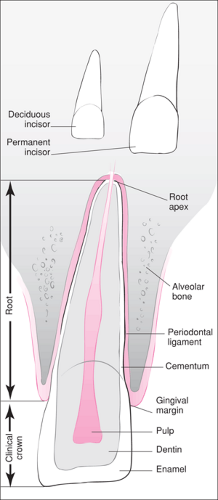

The primary (deciduous) teeth and the secondary (permanent) teeth share a common anatomy, as illustrated in Figure 64.1. The external anatomy of the tooth is divided into two segments, with the gingival margin serving as the dividing line. The clinical crown is the part of the tooth exposed above the margin, whereas the remainder of the tooth below the margin comprises the root. Each tooth is composed of several layers. The external coating of the crown is the enamel, which is the hardest substance in the body. The underlying calcified layer is the dentin. The neurovascular supply, or pulp, is located in the center of the tooth and runs the length of the root. The cementum is an outer layer of calcified material on the root of the tooth. Each tooth is supported in the alveolar bone by fibrous connective tissue known as the periodontal ligament.

Several characteristics, including size, shape, and color, help to distinguish primary from secondary teeth (Table 64.1). This differentiation can frequently be an issue with anterior teeth in the presence of mixed dentition. The age of the child also is a helpful indicator of tooth type. Eruption of the permanent central incisors and first molars generally does not occur until the child has reached 6 to 8 years of age (Table 64.2). Permanent teeth are larger than primary teeth, and their color ranges from white to a yellowish gray. Primary teeth are a milky, opalescent white and have therefore acquired the name “milk teeth.” Primary incisors tend to have a smooth incisal edge, in contrast to the permanent incisors, which are often ridged, especially on the incisal surface. In questionable cases, a radiograph may be useful in demonstrating the presence or absence of a developing permanent tooth.

The maxillary central incisors are prominent and consequently are the most commonly fractured primary and permanent teeth (3,5,6,7,8,9,10). Children with excessive protrusion of the maxillary incisors are especially susceptible to injury. Teeth can fracture in a number of ways (Fig. 64.2). Fractures are classified as complicated or uncomplicated depending on whether the pulp is exposed or not (11). The simplest fractures are those involving only the enamel. The enamel may also sustain an internal fracture or crack that is not evident on visual inspection. An internal fracture line may be seen on transillumination of the tooth. Internal fractures are important to identify because they cause a weakness in the tooth, which can fracture at a later time. These fractures can be easily diagnosed upon dental referral with radiographs. Fractures that involve the dentin can be identified by the presence of a yellow area within the fracture site and an associated sensitivity of the tooth. Because dentin consists of microtubules that communicate with the pulp, exposure of dentin allows insult to the pulp, which can result in inflammation, infection, and eventual necrosis. Fractures resulting in pulp exposure are identified by the presence of a pink area or an actual bleeding spot located in the center of the tooth. Early treatment of dentin and pulpal exposure is crucial in preserving the viability of these teeth (12,13,14).

TABLE 64.1 Differentiating Characteristics of Primary and Secondary Teeth | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Fractures limited to the visible portion of the tooth above the gingiva are crown fractures and involve the enamel, dentin, and occasionally the pulp. Those that are visible above the gingiva but extend into the root of the tooth are crown-root fractures. They involve the enamel, dentin, cementum, and frequently the pulp. These complicated fractures are best handled through dental referral. Isolated root fractures are not visible on the exposed portion of the tooth. The diagnosis is suggested by mobility of the tooth and is confirmed with

radiographs. Root fractures are classified according to their location along the length of the root. They may be classified as cervical, middle, or apical based on their location in relation to the crown of the tooth (Fig. 64.2). The cervical third is adjacent to the clinical crown, and the apical third is located at the root apex. Root fractures usually result in an extruded tooth, with bleeding at the gingiva. The site of the fracture determines the degree of mobility of the tooth, as apical fractures are less mobile. Root fractures are not clinically distinguishable from luxation injuries; thus suspicion of either should lead to referral to the dentist (3).

radiographs. Root fractures are classified according to their location along the length of the root. They may be classified as cervical, middle, or apical based on their location in relation to the crown of the tooth (Fig. 64.2). The cervical third is adjacent to the clinical crown, and the apical third is located at the root apex. Root fractures usually result in an extruded tooth, with bleeding at the gingiva. The site of the fracture determines the degree of mobility of the tooth, as apical fractures are less mobile. Root fractures are not clinically distinguishable from luxation injuries; thus suspicion of either should lead to referral to the dentist (3).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree