Lumbar Puncture

Kathleen M. Cronan

James F. Wiley II

Introduction

Lumbar puncture (LP) is used to obtain cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. In most cases, it is a relatively simple procedure, although it can sometimes prove challenging even for the experienced practitioner. LP is most commonly performed in neonates and infants who, due to both anatomic characteristics and the types of illness they experience, are prone to respiratory compromise during the procedure (1,2). The potential for complications during and following LP therefore dictates that it be performed in an area equipped for resuscitation. Moreover, although not technically complex, LP is by no means a trivial procedure, and it should only be performed or supervised by a health professional with appropriate training who is knowledgeable about the indications and contraindications for the procedure. For some patients, LP can only be safely performed after brain imaging excludes a space-occupying central nervous system (CNS) lesion and/or elevated intracranial pressure. For patients with shock or respiratory compromise also suspected of having meningitis or encephalitis, stabilization of the patient and presumptive antibiotic therapy must precede LP. These considerations require careful patient evaluation and selection before performing LP.

Anatomy and Physiology

CSF is found in the space between the pia mater and the arachnoid mater that surrounds the brain, spinal cord, ventricles, aqueduct, and central canal of the spinal cord. Most CSF is formed in the choroid plexuses of the lateral ventricles. After formation, CSF flows out the foramina of Luschka and Magendie into the subarachnoid space, around the spinal column, and over the cerebrum. The CSF is primarily absorbed by the arachnoid villi located adjacent to the sagittal sinus and then returned to the venous circulation (3).

The average total volume of CSF in children is approximately 90 mL. For full-term infants, the volume is about 40 mL. One quarter of the volume is located in the ventricles, and the remainder in the subarachnoid space. CSF provides physical cushioning between bony structures and the brain and spinal cord (4). It expands and contracts to offset changes in the size of the brain (e.g., cerebral edema) as well as changes in arterial and venous volumes (e.g., cortical atrophy, parenchymal injury) (5). CSF also has an important role in transferring chemical byproducts of metabolism from the brain to the venous circulation.

At birth, the inferior end of the spinal cord is opposite the body of the third lumbar vertebra (L3). As the child’s

spinal cord grows, the vertebral column grows more rapidly. In the adult, the caudal aspect of the cord lies opposite the inferior border of the first lumbar vertebra. Of note, the spinal cord rises slightly when the trunk of the body is bent forward (3,6).

spinal cord grows, the vertebral column grows more rapidly. In the adult, the caudal aspect of the cord lies opposite the inferior border of the first lumbar vertebra. Of note, the spinal cord rises slightly when the trunk of the body is bent forward (3,6).

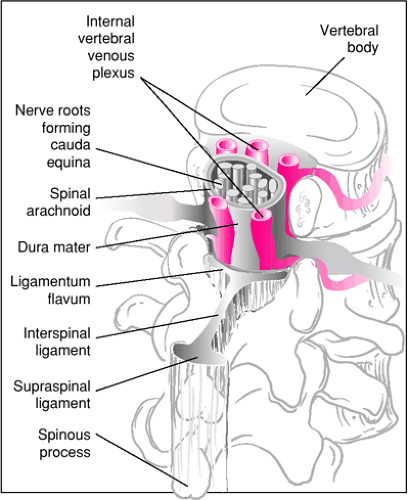

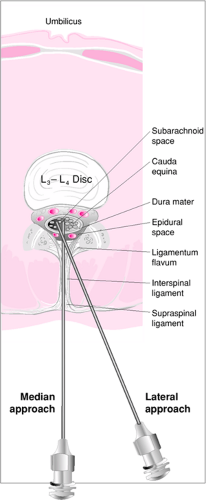

Structures pierced during median LP are (in order) skin, subcutaneous fat, supraspinal ligament, interspinal ligament, ligamentum flavum, dura mater, and arachnoid mater (Fig. 41.1). In older patients, supraspinal and interspinal ligaments are sometimes calcified, which may require a lateral approach (Fig. 41.2). However, this is rare in children, and the median approach is therefore most commonly used (7).

Indications

For the pediatric patient, the primary emergent reason for LP is suspicion of CNS infection (meningitis, encephalitis). Fever, paradoxic irritability (increased crying when held), and bulging anterior fontanel are classic findings associated with bacterial meningitis in the infant. Fever, headache, neck pain/stiffness, confusion, or meningismus manifested by Brudzinski sign (pain on flexion of the neck) or Kernig sign (pain on extension of the knee when the hips are flexed to 90 degrees) may be present in older children with bacterial meningitis. The hallmark of encephalitis is meningeal irritation accompanied by abrupt onset of mental status changes. Signs of meningitis may be subtle in neonates, young infants,

and patients taking oral antibiotics (i.e., with so-called “partially treated” meningitis) (8). Furthermore, patients with viral or Lyme meningitis often have fewer clinical signs. Patients with a complex febrile seizure are also at increased risk for concurrent meningitis (9). It is important to remember that meningismus may not be detectable in patients with meningitis who are comatose or have neurologic impairment. Furthermore, meningismus may be present in children who have conditions other than meningitis, such as a posterior fossa brain tumor, retropharyngeal abscess, upper lobe pneumonia, cervical diskitis, and pyelonephritis (8).

and patients taking oral antibiotics (i.e., with so-called “partially treated” meningitis) (8). Furthermore, patients with viral or Lyme meningitis often have fewer clinical signs. Patients with a complex febrile seizure are also at increased risk for concurrent meningitis (9). It is important to remember that meningismus may not be detectable in patients with meningitis who are comatose or have neurologic impairment. Furthermore, meningismus may be present in children who have conditions other than meningitis, such as a posterior fossa brain tumor, retropharyngeal abscess, upper lobe pneumonia, cervical diskitis, and pyelonephritis (8).

Suspected spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage constitutes another urgent indication for LP. Patients with suspected intracranial bleeding should have a brain imaging study before LP in most instances. A small percentage of subarachnoid hemorrhages are not detectable on a CT scan of the head, and LP becomes the sole method of diagnosing this problem (9). LP also is performed in a variety of nonacute situations, such as the administration of chemotherapeutic agents, injection of radiopaque dye for spinal cord imaging, diagnosis of CNS metastases, treatment of pseudotumor cerebri, and measurement of opening pressure to rule out specific disease entities.

Contraindications to LP include the presence of infection in the tissues near the proposed puncture site, evidence of spinal cord trauma or spinal cord compression, an uncorrected severe coagulopathy, and signs of progressive cerebral herniation. LP may also be contraindicated based on the condition of the patient. If a patient has an unstable airway, a potentially dangerous breathing problem (e.g., apnea), and/or severe circulatory instability, the stress of being restrained in the correct position for LP may cause an abrupt (and often undetected) decompensation. As mentioned previously, this is especially true of young infants. In these situations, suspected infection should be treated presumptively, without performing the LP, using appropriate antimicrobial therapy (8).

Extreme caution should be exercised, and the procedure generally avoided, when a patient has elevated intracranial pressure resulting from a space-occupying intracranial lesion. Such conditions include brain tumor, cerebral hemorrhage, cavernous sinus thrombosis, brain abscess, and epidural or subdural collection. Focal neurologic findings in conjunction with one of these conditions should be interpreted as signs of impending herniation and serve as an absolute contraindication to LP. Although an unlikely outcome, dexamethasone or mannitol infusion may be helpful if increased intracranial pressure from an unsuspected mass lesion is encountered or signs of cerebral herniation occur during or after LP (10,11).

Patients with a known spinal column deformity should have the procedure performed under fluoroscopy. LP cannot access the subarachnoid space in patients who have undergone posterior spinal fusion in the lumbar region, because needle entry is blocked by bone. These patients require a cisternal tap for CSF collection, a procedure that is performed by a neurosurgeon. In all circumstances where LP might cause harm to the patient, risks and potential benefits must be evaluated thoroughly before performing the procedure.

TABLE 41.1 Spinal Needle Size by Age | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

An important point to remember is that for the great majority of patients managed in the ED, LP is merely a test, not a therapy. A patient will rarely have an adverse outcome simply because they did not undergo LP. A common mistake that must be avoided is delaying treatment that will affect outcome (e.g., administration of antibiotics) for the sake of obtaining a “clean” LP. If a patient is suspected of having a potentially life-threatening CNS infection, and LP cannot be performed on a timely basis (e.g., the patient is currently unstable, the clinician is uncomfortable with the procedure), then appropriate antimicrobial therapy must be administered as quickly as possible to protect the patient. The consequences of an imperfect test can be dealt with later.

Equipment

Sterile gloves

Betadine solution

LP tray:

Sterile drapes

Betadine swabs or tray to pour Betadine

Sterile sponges for preparing the puncture site

Sterile 3-mL syringe with needle for lidocaine injection

Sterile collecting tubes

Sterile spinal needle (Table 41.1)

Manometer (may be a separate sterile item to be added to tray)

Injectable lidocaine 1% without epinephrine

Eutectic mixture of lidocaine and prilocaine (EMLA) or lidocaine 4% cream (LMX-4)

Midazolam or other anxiolytic agent

Procedure

The indication for LP and potential complications should be explained fully to the patient (if appropriate) and the parents. Many institutions require written informed consent before the procedure. The consent form may be standardized within the hospital or tailored to the individual setting. The consent form should include a description of the procedure as well as the benefits and risks of the procedure. Monitoring of heart rate, respirations, and oxygen saturation should be strongly considered during the procedure, particularly in neonates, young infants, and children with any degree of cardiorespiratory

compromise. Airway and resuscitation equipment should be immediately available. If the LP is being performed for elective reasons, 4% lidocaine cream (LMX-4) or eutectic mixture of lidocaine and prilocaine (EMLA) may be applied over the puncture site to anesthetize the area (see also Chapter 35). LMX-4 is effective after about 30 minutes, and EMLA is effective after about 45 to 60 minutes (12,13). Given the shorter time frame for onset of effect with LMX-4, it may be the preferred agent for this purpose.

compromise. Airway and resuscitation equipment should be immediately available. If the LP is being performed for elective reasons, 4% lidocaine cream (LMX-4) or eutectic mixture of lidocaine and prilocaine (EMLA) may be applied over the puncture site to anesthetize the area (see also Chapter 35). LMX-4 is effective after about 30 minutes, and EMLA is effective after about 45 to 60 minutes (12,13). Given the shorter time frame for onset of effect with LMX-4, it may be the preferred agent for this purpose.

Achieving and maintaining proper patient position is the most crucial and challenging aspect of LP in children. Having an experienced assistant to perform this task is invaluable. The patient is placed on the examining table, and the operator is typically seated next to the bed, although some clinicians choose to stand with the bed elevated. The goals of positioning are to stretch the ligamenta flava and increase the interlaminar spaces. The two positions most widely used in the pediatric population are the lateral recumbent position and the sitting position (Fig. 41.3).

For the lateral recumbent position, the patient lays on his or her side near the edge of the bed next to the operator. For the right-handed operator, the patient’s head is usually facing left. The patient’s neck is flexed and the knees are drawn upward by the assistant. This is done by placing one arm under the child’s knees and the other arm around the posterior aspect of the neck. By grasping his or her own wrists (with smaller patients), the assistant can maintain a greater degree of control over the restraint of the child. The assistant also should ensure that the shoulders and hips are perpendicular to the bed, thus keeping the spinal column in line, with no rotation. To increase the size of the interlaminar spaces, the cooperative patient can be asked to fully bend his or her back toward the physician.

The sitting position can be used with older children who are cooperative and with very young infants who are unlikely to struggle and may have increased respiratory distress in the lateral recumbent position (2). An older child may sit with feet over the side of the bed and with neck and upper body flexed over a pillow or a pile of blankets held in the lap. With an infant, the assistant holds the patient in a sitting position with an arm and a leg in each hand while supporting the head to prevent excess flexion of the neck (Fig. 41.3).

Once the patient is positioned, the upper aspects of the posterior superior iliac crests are palpated, and an imaginary line between them is pictured. This line intersects the midline just above the fourth lumbar spine. The interspaces between L3-L4 and L4-L5 can then be located, and one site is chosen for puncture (Fig. 41.3). In children outside infancy, the interspace between L2-L3 also may be used for LP.

After the puncture site has been selected, it should be cleansed with Betadine-soaked, sterile gauze or sponge using enlarging circles that begin at the puncture site. The Betadine solution may then be removed with alcohol in the same manner. Sterile towels are draped around the procedure site in such a way as to allow for good exposure. The puncture site should be relocated as previously described, and the site can be marked with a fingernail depression in the skin.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree