becomes intraperitoneal as the jejunum, which is approximately 8 feet in length. An arbitrary transition to the ileum occurs, which is approximately 12 feet in length and terminates at the ileocecal junction in the right lower quadrant of the peritoneal cavity. Clinically, the jejunum is slightly thicker and greater in diameter, more vascular, and of deeper color.

point—either at the ligament of Treitz (moving forward) or at the ileocecal valve (moving backward)—to ensure complete adhesiolysis.

TABLE 47.1 Primary Cytoreduction; % Colon Resection | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TABLE 47.2 Secondary Cytoreduction: % Colon Resection | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TABLE 47.3 Segments of Bowel Resected for Primary Cytoreduction | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

TABLE 47.4 Primary Cytoreduction | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

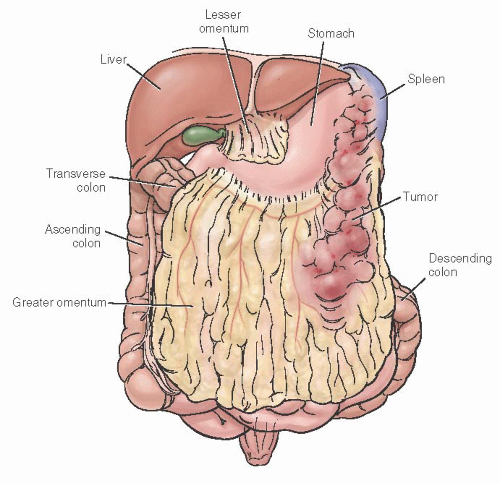

colon, cecum, and terminal ileum. Appendiceal endometriosis is generally an incidental finding not clinically significant. The most important potential consequence of bowel involvement is obstruction, which is more likely to occur in the small intestine. Other clinically significant consequences include pain (from dyschezia, tenesmus, dyspareunia, or nonspecific pelvic, or rectal), cyclic rectal bleeding, and nonspecific bowel symptoms. Further, the fibrotic mass effect and symptoms of bowel endometriosis may create the suspicion of malignancy.

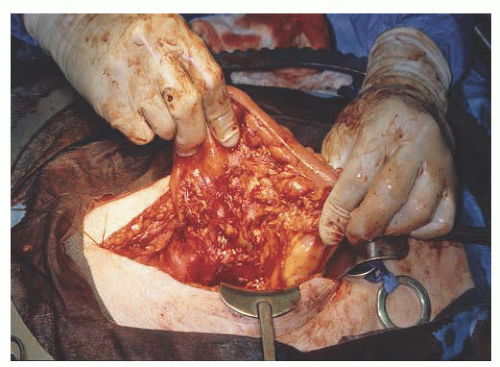

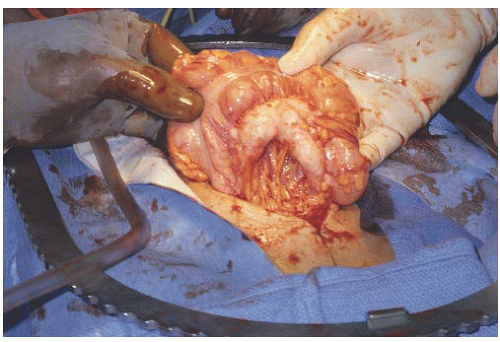

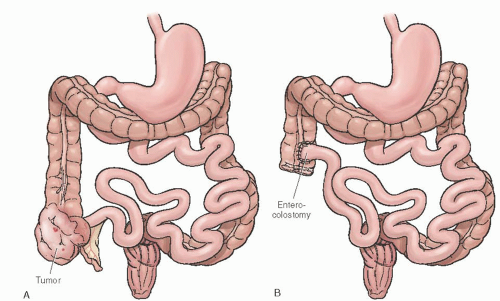

FIGURE 47.10 A: Ovarian cancer involving cecum. B: Right hemicolectomy with ileo-ascending enterocolostomy. |

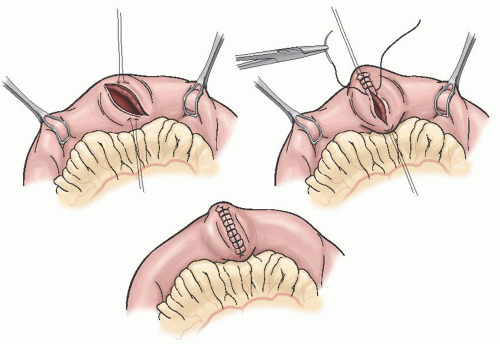

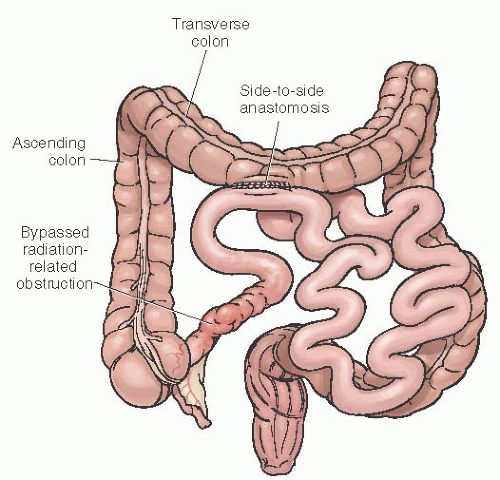

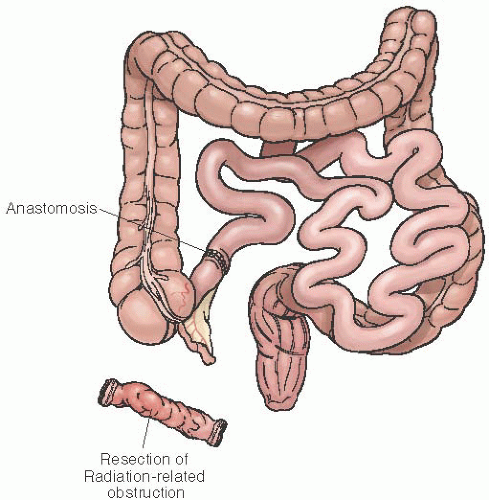

both areas should be evaluated prior to surgical intervention. Surgical management of radiation-related small bowel obstruction remains controversial. Some experts recommend bypass of the obstruction while others believe the damaged bowel should be resected with primary reanastomosis. Simple bypass involves a side-to-side anastomosis of the proximal uninvolved small bowel to a relatively nonirradiated portion of the colon (Fig. 47.12). This is the fastest and least complicated surgical intervention. Advantages include the avoidance of extensive dissection of matted loops of the bowel—which dissection presents a potential for injury—in the resultant raw, previously irradiated pelvis. The side-to-side anastomosis ensures a good blood supply, avoids the need for a mucous fistula, and may allow the remainder of the bowel to provide some absorptive capacity in cases of partial obstruction; this is especially important when there is a short afferent limb. It also minimizes the risk of injury to other organs or structures, such as the ureter or vascular system. Overall, the results of simple bypass for these patients are reasonably good.

FIGURE 47.12 Simple side-to-side anastomosis of proximal small bowel to transverse colon in order to bypass radiation-related obstruction of the terminal ileum. |

FIGURE 47.13 Enterocolostomy that both bypasses and diverts the fecal stream from the obstructed ileum. |

FIGURE 47.14 Resection of obstructed, damaged bowel with anastomosis of small bowel to unirradiated transverse colon. |

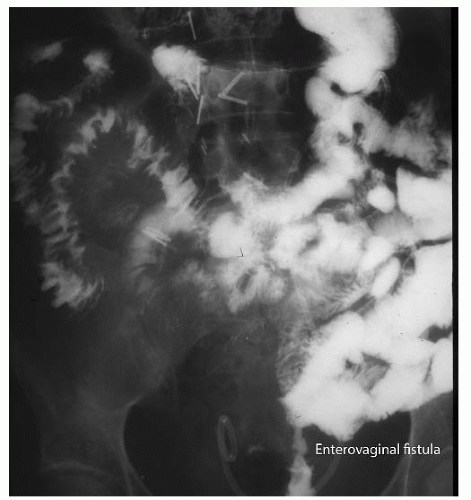

FIGURE 47.15 Contrast study demonstrating enterovaginal fistula. Note that the contrast passes from the distal small bowel into the vagina in the center lower area of this radiograph. |

Bricker described the technique of folding the rectosigmoid colon over itself to cover the fistula with anastomosis of the colon to the top of the loop.

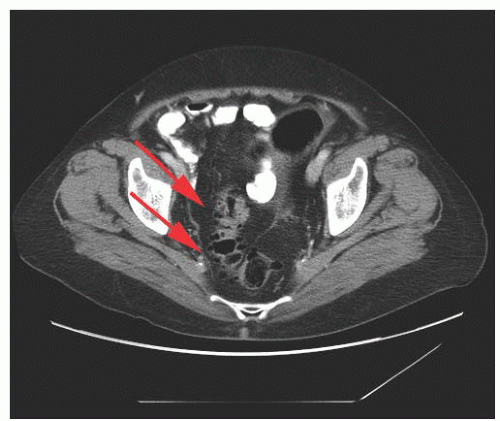

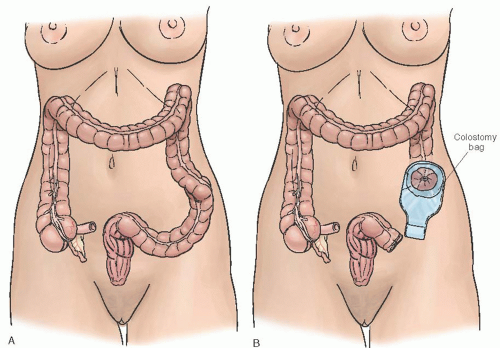

resumption of normal bowel activity). At initial presentation, if the suspicion for cancer is high, then surgical exploration with Hartmann procedure (i.e., resection, end colostomy, rectal pouch) is the safest and most effective diagnostic and therapeutic intervention (Fig. 47.18).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree