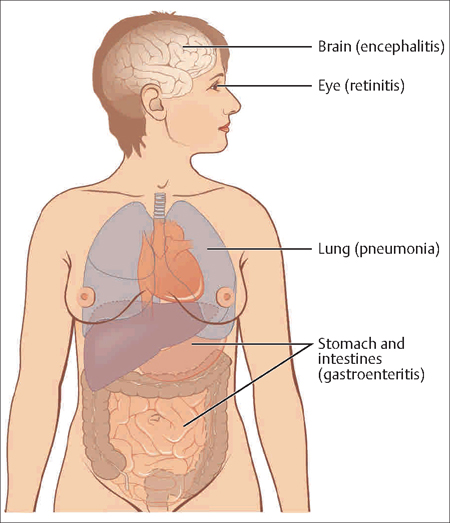

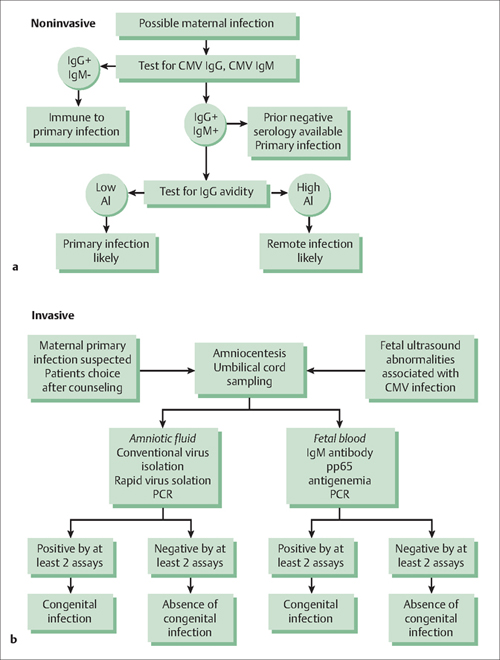

23 Infectious Diseases in Pregnancy Felicitas von Petery and Gustavo Leguizamón When a woman is pregnant, an infection can be more than just a problem for her. Some infections can imperil her baby as well. For example, when a pregnant woman becomes infected with cytomegalovirus, which is normally a benign infection in adults and even children, she can pass the virus on to her fetus. In a small, yet significant, number of cases, cytomegalovirus-infected new-borns develop serious illnesses or lasting disabilities, and even die. Due to the ever-present risk of infectious pathogens, pregnant women often need to take medicines or get vaccinated to prevent their babies from also becoming infected. However, only a selected number of medicines and vaccines are safe to take during pregnancy. Thus, OB/ GYN physicians need to understand not only the potential consequences for the mother of various types of infections during pregnancy, but also the potential negative consequences for the baby of available medicines and treatment approaches. This chapter covers the major types of infections that occur during pregnancy and are likely to cause complications for the fetus—excluding human papilloma virus, which is covered in Chapter 6, and puerperal endometritus (Chapter 22). Also covered are the most recent, evidence-based approaches for diagnosing and managing major infectious diseases in pregnancy. Avidity index: This indicates the degree of antibody avidity toward a specific antigen, helping to differentiate between a recent versus an old infection. Hematogenous: This means spread by the blood. Latency: This word describes the dormant asymptomatic state observed after the clearance of an acute infection. Lymphadenopathy: This is a disease state that is characterized by abnormally enlarged lymph nodes. Malaise: This condition presents a general feeling of fatigue or vague discomfort. Myalgia: This is a term for pain in one or more muscles. Paresthesia: This is a term given to an abnormal neurological sensation, usually perceived as numbness, tingling, burning, or prickling. Thrombocytopenia: This term is used to describe an abnormal decrease in the number of platelets in the blood. Vertical transmission: Transmission of an infection from mother to child during the prenatal period, during delivery, or via breast feeding. Viral titer: This expression is used for the measurement of the amount of virus present in blood. Viremia: This describes the presence of a virus in the blood. Viruses are very tiny capsules with genetic material inside. Some cause familiar infectious diseases such as the common cold, influenza, and warts. They also cause more severe illnesses such as AIDS, hepatitis, and cancer. Viruses invade living, normal cells and use those cells to multiply and produce other virus particles like themselves. This process eventually kills the cells, which can make the infected person sick. If that person is pregnant, her baby can become sick as well. Viral infections are hard to treat because viruses live inside the body’s cells, and they are often “protected” from treatments by their host cells. Antibiotics do not generally work against viral infections. Although a few antiviral medicines are available. However, vaccines are the best way to prevent a woman from getting many viral diseases. In addition to human papilloma virus (see Chapter 6), other major viral infections for which pregnant women need to be monitored include cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a double-stranded DNA virus and a member of the herpes virus family. It is endemic throughout the world, afecting individuals in all social and demographic areas. It represents the most common cause of congenital viral infection. Among healthy individuals, viral transmission typically requires repeated and prolonged contact. Infection is mainly asymptomatic, with incubation periods varying from 20 days to 2 months. The infection may result in complications throughout the body (Fig. 23.1). Symptoms usually involve fever, malaise, headache, and myalgia. Lymphadenopathy may be present. Laboratory findings may include elevated liver enzymes, atypical lymphocytes, and thrombocytopenia. Individuals with chronic CMV infection may develop pneumonia, gastroenteritis, retinitis, or encephalitis. Fig. 23.1 Cytomegalovirus infection can impact many organs and systems in the body, including the brain, eyes, lungs, stomach, intestines, and liver. During the initial infection, viremia occurs. Peak titers of immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies can usually be detected 1–3 months after the onset of infection. Viral titers decline to undetectable levels by 12 months, but they can persist up to 18 months. After the resolution of the primary infection, the virus establishes latency within host tissues and can be isolated in blood and secretions. Most infections resolve spontaneously within 2–6 weeks. Secondary complications of primary CMV infection include hepatitis and pneumonia. Approximately 50% of pregnant patients are seropositive for CMV antibodies. The incidence of primary infection during pregnancy ranges from 1% to 4%, with 5% to 68% of patients presenting clinical symptoms. Initially, diagnosis of maternal infection is established by determining the IgG, IgM, and IgG avidity indexes in the blood (Fig. 23.2). When these results indicate high probability of a recent infection, the mother should be counseled and offered more invasive diagnostic testing for fetal infection. A first-time (primary) CMV infection during pregnancy results in a 30–40% risk of vertical transmission to the fetus. In contrast, the risk of transmission with recurrent maternal infection is between 0.2% and 1.8%. The most likely pathway for congenital CMV is via blood transmission to the fetus. Placental infection occurs first, followed by replication of the virus and transfer to the fetus. Once the fetal infection occurs, the virus replicates in the renal tubular endothelium and is excreted into the amniotic fluid. The cycle then can repeat itself. Finally, neonates can acquire the infection through breastfeeding. Only 10–15% of infected neonates are symptomatic at birth. Among infected infants, asymptomatic at birth, 5–15% will develop sequelae later in life (Table 23.1; Evidence Box 23.1). The symptoms of congenital, fetal CMV infection appear to be related to the timing of maternal infection. Infection during the first half of pregnancy, for example, is associated with symptomatic disease, whereas infection in the latter half is more commonly associated with initially asymptomatic disease. Because there are no effective therapies for congenital CMV infection, prevention in the mother is ideal. Several vaccines have been developed that prevent maternal CMV infection. However, many physicians are reluctant to use these vaccines to immunize women of childbearing age, because their safety has not been properly established. Also, reports of new infections in previously immune patients have raised questions about the efficacy of CMV vaccination in general. Fig. 23.2a, b Diagnostic options flow chart, if maternal cytomegalo-virus (CMV) infection is suspected.

Definitions

Viral Infections

Cytomegalovirus

Clinical Manifestations

Diagnosis of Maternal and Fetal Infection

Prevention

| Antenatal ultrasonographic findings | Early postnatal findings | Late findings |

| Microcephaly | Microcephaly | Developmental delay |

| Periventricular calcifications | Periventricular calcifications | Mental retardation |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | Ventriculomegaly | Seizures |

| Ventriculomegaly | Chorioretinitis | Visual impairment |

| Echogenic bowel | Hyperbilirubinemia | Sensorineural hearing loss |

| Hepatosplenomegaly | Hepatosplenomegaly | |

| Fetal Growth Restriction | Hepatitis | |

| Growth delay |

Thus, women of childbearing age need to be educated about CMV and how it is transmitted, so they are not at risk. They should also be taught how to be careful in handling potentially infected articles, such as diapers, and about the need to thoroughly wash their hands if they are exposed to young children or immunocompromised individuals. Although universal screening is not currently recommended, high-risk women need to be counseled about serologic screening before pregnancy.

Herpes Simplex Virus

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) is a double-stranded DNA virus (Fig 23.3) transmitted by direct and intimate contact. Following primary infection, the virus remains latent in neuronal ganglia to reactivate at later times. There are two identified strains of HSV: type 1, which causes oropharyngeal lesions; and type 2, which is responsible for genital tract infections. Twenty-two percent of pregnant women are seropositive for HSV-2 and more than 2% of women acquire the infection during pregnancy.

Clinical Manifestations

Only 30% of pregnant women are symptomatic to primary infection, with manifestations ranging from mild discomfort to widespread genital lesions associated with pain, dysuria, tender regional lymph node enlargement, fever, and malaise.

Fig. 23.3 The herpes simplex virus, pictured here, causes long-term persistent infection in most affected individuals.

HSV infections are classifed as primary, nonprimary first episode, and recurrent (Table 23.2). Lesions are usually preceded by paresthesias, followed by the eruption of vesicles, which rupture forming a shallow-based ulcer that develops into a crust. Eventually all lesions heal without scarring.

Diagnosis

Isolation of HSV in cell culture is performed in patients who present with genital lesions. The sensitivity of viral culture is low, and decreases with reactivations and as lesions begin to heal.

Commercially-available polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays for HSV are more sensitive and can be used instead of cell cultures. The lack of HSV detection both by PCR and in culture does not exclude HSV infection, because viral shedding is intermittent.

In women who lack lesions, use type-specific serology for HSV, or diagnostic culture and/or PCR assay. If infection is suspected and all tests are negative, repeat serology in 6 weeks.

Perinatal Transmission

Transmission to the fetus can occur during the antepartum or intrapartum period by different mechanisms. Antepartum infections are associated with a potential risk for hematogenous spread to the fetus. On the other hand, when intrapartum transmission occurs, it is usually secondary to direct exposure to maternal viral shedding in vaginal secretions. Finally, neonatal transmission may occur secondary to close contact with infected individuals.

Perinatal transmission rates vary according to the type of infection:

- primary: 50%

- nonprimary first episode: 33%

- recurrent: 0–4%

| Primary | First clinical infection |

| No pre-existing antibody | |

| Nonprimary/first episode | No history of genital infection |

| Positive antibody to the other type of virus (HSV-1/HSV-2) | |

| Recurrent | Prior history of clinical infection |

| Positive antibody to same type of virus |

| Indication | Acyclovir | Valacyclovir |

| Primary of first episode HSV | 400 mg p.o., t.i.d. for 7–14 days | 1 g b.i.d. for 7–14 days |

| Symptomatic recurrent HSV | 400 mg p.o., t.i.d. for 5 days | 500 mg bid for 5 days |

| Daily suppressive therapy | 400 mg p.o., t.i.d. | 500 mg p.o. daily |

Treatment and Preventive Strategies

All pregnant women must be asked during prenatal care about any history of genital herpes and counseled to avoid intercourse with infected individuals. If they do become infected, either one of the antiviral drugs acyclovir or valacyclovir may be administered, depending on the scenario (Table 23.3).

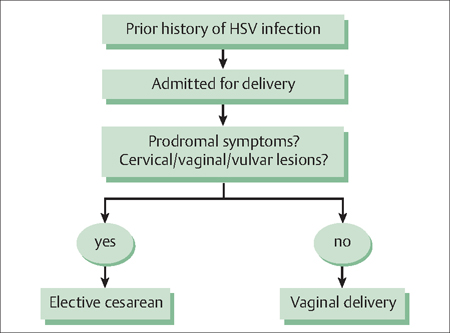

At the onset of labor, women should be questioned about symptoms of genital herpes and carefully evaluated for presence of vaginal or cervical lesions. Women without evidence of genital herpes can deliver vaginally, while those with either primary or recurrent lesions should undergo cesarean section to decrease the risk of perinatal transmission (Fig. 23.4).

Pregnancy in the HIV Era

Women account for a disportionately increasing number of new cases of HIV infection throughout the world. The prevalence of infected women of childbearing age has also increased as a result of the decreasing mortality associated with the advent of combined antiretroviral therapy and higher rates of heterosexual transmission.

In 2005, UNAIDS (the Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS) estimated that 38.6 million people had HIV, of whom 17.3 million were women (with most being in their reproductive years). At least 3.28 million pregnant women infected with HIV are estimated to give birth each year, with more than 75% of these in sub-Saharan Africa. Most of the annual 700 000 new infections of HIV in children in sub-Saharan Africa occur via vertical transmission.

Fig. 23.4 Intrapartum approach for women with herpes simplex virus.

The management of HIV infection during pregnancy involves two major goals: the prevention of disease progression in the mother, and vertical transmission to the new born.

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

The HIV virus particle is 100–120 nm in diameter, with a spherical morphology. Its cone-shaped core is surrounded by a lipid matrix containing key surface antigens and glycoproteins. The viral core contains two copies of genomic RNA, reverse transcriptase, integrase, and proteases (Fig. 23.5). Gp120, a glycoprotein present in the viral surface, binds to cells bearing CD4 receptors, causing a change in their shape. This allows the virus to bind to other receptors on the cell and to fuse its membrane with the cell’s membrane. Once this occurs, HIV empties it contents into the cytoplasm of the cell.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree