Background

Zika virus infection during pregnancy is a known cause of congenital microcephaly and other neurologic morbidities.

Objective

We present the results of a large-scale prenatal screening program in place at a single-center health care system since March 14, 2016. Our aims were to report the baseline prevalence of travel-associated Zika infection in our pregnant population, determine travel characteristics of women with evidence of Zika infection, and evaluate maternal and neonatal outcomes compared to women without evidence of Zika infection.

Study Design

This is a prospective, observational study of prenatal Zika virus screening in our health care system. We screened all pregnant women for recent travel to a Zika-affected area, and the serum was tested for those considered at risk for infection. We compared maternal demographic and travel characteristics and perinatal outcomes among women with positive and negative Zika virus tests during pregnancy. Comprehensive neurologic evaluation was performed on all infants delivered of women with evidence of possible Zika virus infection during pregnancy. Head circumference percentiles by gestational age were compared for infants delivered of women with positive and negative Zika virus test results.

Results

From March 14 through Oct. 1, 2016, a total of 14,161 pregnant women were screened for travel to a Zika-affected country. A total of 610 (4.3%) women reported travel, and test results were available in 547. Of these, evidence of possible Zika virus infection was found in 29 (5.3%). In our population, the prevalence of asymptomatic or symptomatic Zika virus infection among pregnant women was 2/1000. Women with evidence of Zika virus infection were more likely to have traveled from Central or South America (97% vs 12%, P < .001). There were 391 deliveries available for analysis. There was no significant difference in obstetric or neonatal morbidities among women with or without evidence of possible Zika virus infection. Additionally, there was no difference in mean head circumference of infants born to women with positive vs negative Zika virus testing. No microcephalic infants born to women with Zika infection were identified, although 1 infant with hydranencephaly was born to a woman with unconfirmed possible Zika disease. Long-term outcomes for infants exposed to maternal Zika infection during pregnancy are yet unknown.

Conclusion

Based on a large-scale prenatal Zika screening program in an area with a predominantly Hispanic population, we identified that 4% were at risk from reported travel with only 2/1000 infected. Women traveling from heavily affected areas were most at risk for infection. Neonatal head circumference percentiles among infants born to women with evidence of possible Zika virus infection during pregnancy were not reduced when compared to infants born to women without infection.

Introduction

Zika virus has emerged in the last year as the first major teratogenic arbovirus responsible for an epidemic of congenital microcephaly in the Western Hemisphere. Surveys of local Zika virus transmission in countries such as Brazil, Columbia, and Puerto Rico have provided estimates of cumulative incidences in the general population, as well as among pregnant women. Attempts to quantify the number of Zika virus infections in both pregnant and nonpregnant women in an affected population, however, have been hampered by the apparent lack of clinical symptoms in approximately 80% of infections, and the inherent limitations of currently available diagnostic tests. In February 2016, in an effort to increase detection of Zika virus infection in asymptomatic pregnant women, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended testing all pregnant women who traveled to a Zika-affected area. The ongoing effort to screen and counsel pregnant women was complicated by the fact that the epidemic continued to spread north throughout early 2016. In July 2016, local Zika virus transmission in the United States was determined in a cluster of confirmed cases in Miami-Dade County, Florida. In November 2016, the CDC began to investigate the first suspected locally transmitted cases of Zika virus disease in Brownsville, TX. With locally transmitted disease now reported in the United States, states with high travel volume such as California, Florida, New York, and Texas remain at continued risk for both travel-associated and locally transmitted Zika virus infections.

We now report our experience with a large-scale, prenatal Zika screening program in Dallas, TX. This epidemiologic study was intended to establish the baseline risk for travel-associated maternal Zika virus infection, to evaluate the travel characteristics of at-risk women with evidence of Zika infection, and to describe the outcomes among neonates exposed to maternal Zika virus infection in our predominantly Hispanic pregnant population.

Materials and Methods

This was a prospective, observational study of Zika virus screening in our health care system from March 14 through Oct. 1, 2016. Parkland Hospital serves the medically indigent women of Dallas County through an administratively and medically integrated public health care system. Pregnant women are routinely assigned to a Parkland neighborhood clinic for antenatal and postpartum care. Using an electronic health record–associated best practice alert (BPA) implemented at 11 different Parkland prenatal clinics, we screened all pregnant women receiving prenatal care for travel to an area with active Zika transmission. The BPA is an electronic reminder triggered within the medical record at the initiation of prenatal care, which prompted the provider to ask a series of 3 cascading questions. These questions referred to a list of areas considered to have local Zika transmission by the CDC, and the list was updated periodically to reflect the evolving epidemic. At the time of this publication, no local transmission of Zika virus had been confirmed in the Dallas area. For each woman reporting travel, a detailed travel history and review of compatible symptoms were recorded in the subsequent BPA questions.

Laboratory evaluation

Serum testing with the Food and Drug Administration–approved Zika IgM antibody capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and/or real-time reverse transcription (rRT)-polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed for all women with positive travel screens who met extant CDC criteria. Laboratory testing was performed by the Dallas County Health and Human Services (DCHHS) and the CDC. Testing was based on the time interval between last exposure (ie, last date of travel) or symptom onset and the date of screening. Serum IgM was performed by DCHHS for specimens collected >2 weeks after travel in asymptomatic and symptomatic pregnant women, up to 9 months after return from travel. Presumptive positive or equivocal serum IgM specimens were forwarded by DCHHS to the CDC for confirmatory plaque reduction neutralization (PRNT) testing. Serum rRT-PCR for Zika virus RNA was performed by DCHHS on any specimen collected within 4 weeks of symptom onset or within 6 weeks of return from travel. Serum screening alone was implemented at our institution prior to the development of CDC guidelines regarding urine testing. In August 2016, following release of the interim guidance for urine testing and evaluation of pregnant women, we implemented rRT-PCR testing of subsequent urine specimens for pregnant women with presumptive positive or equivocal serum IgM.

Ultrasound evaluation

Detailed fetal anatomic survey was performed for all at-risk women, with assessment for specific findings such as intracranial calcifications, microcephaly, ventriculomegaly, abnormal corpus callosum, cortical abnormalities, and cerebellar hypoplasia. Additional ultrasounds were performed for fetal growth assessment in women with either positive or unknown IgM results as recommended by the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Women with negative Zika virus IgM results received routine prenatal care. Women with presumptive positive or equivocal serum IgM results or with abnormal fetal ultrasound findings suggestive of intrauterine infection were referred to a dedicated maternal-fetal medicine clinic. The clinic is staffed by fellows and faculty from the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center with expertise in infectious disease affecting pregnancy. When intrauterine infection was suspected, further evaluation was conducted, including amniocentesis when indicated. Women received comprehensive counseling regarding laboratory testing, ultrasound results, the need for evaluation at the time of delivery, and the plan for postnatal follow-up in this clinic.

Infant evaluation

At the time of delivery, maternal and neonatal specimens were sent to the local health department for women with known or suspected recent Zika infection, and for those at risk for Zika infection without prior screening results. Placental and umbilical cord tissue samples were sent to CDC for rRT-PCR testing for Zika virus RNA. Umbilical cord blood was routinely sampled at delivery until late July 2016, when the CDC guidelines for evaluation of infants at risk for congenital Zika infection changed to recommend infant serum collected within the first 2 days after birth.

The scope of neonatal evaluation evolved during the study period. Initially, the CDC recommended testing only infants born with microcephaly or intracranial calcifications, or those born to mothers with positive or inconclusive Zika testing results. For these infants, PCR and serologic testing of umbilical cord blood or infant serum collected within 2 days of birth was recommended. Routine care was recommended for infants with normal prenatal imaging and postnatal physical examinations born to at-risk mothers for whom Zika virus testing was not performed. In July 2016, Zika testing on umbilical cord blood was no longer recommended by the CDC. This change was implemented in our hospital the same month. In August 2016, CDC recommended that for infants with normal prenatal imaging and postnatal physical examinations born to at-risk women not previously tested, evaluation should begin with maternal Zika testing, with subsequent infant testing if maternal results were positive or indeterminate.

Comprehensive physical exam and standard newborn hearing screen using auditory brainstem response testing were routinely performed on all infants soon after birth regardless of Zika results. Head circumference and gestational age-specific head circumference percentile for each infant was assessed using the gender-specific growth curves developed and validated by Olsen et al and currently in use at Parkland Hospital. Microcephaly was defined as head circumference <3rd percentile for gestational age.

Additional neonatal evaluation for possible congenital Zika virus infection was performed on a case-by-case basis according to evolving CDC guidelines, including urine testing, head ultrasound, and complete ophthalmologic assessment. For infants with abnormal findings, evaluation was conducted for other intrauterine infections, such as cytomegalovirus (CMV), toxoplasmosis, syphilis, or rubella virus, as appropriate.

Beginning September 2016, infants born to women with evidence of Zika virus infection during pregnancy were assigned to follow-up after delivery with both a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Children’s Medical Center Dallas, and a pediatric primary care provider. Developmental testing and infant follow-up was planned for these infants according to CDC guidelines.

Delivery outcomes and statistical analysis

Demographics and perinatal outcomes of delivered women were linked to an existing obstetric database. The database contained maternal and infant outcomes for all women delivered at Parkland Hospital. Categorical and continuous variables were compared among women with positive and negative Zika results using χ 2 and Student t tests, respectively, and P < .05 was considered significant for all analyses. Statistical analysis was performed using software (SAS 9.3; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). This study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

Materials and Methods

This was a prospective, observational study of Zika virus screening in our health care system from March 14 through Oct. 1, 2016. Parkland Hospital serves the medically indigent women of Dallas County through an administratively and medically integrated public health care system. Pregnant women are routinely assigned to a Parkland neighborhood clinic for antenatal and postpartum care. Using an electronic health record–associated best practice alert (BPA) implemented at 11 different Parkland prenatal clinics, we screened all pregnant women receiving prenatal care for travel to an area with active Zika transmission. The BPA is an electronic reminder triggered within the medical record at the initiation of prenatal care, which prompted the provider to ask a series of 3 cascading questions. These questions referred to a list of areas considered to have local Zika transmission by the CDC, and the list was updated periodically to reflect the evolving epidemic. At the time of this publication, no local transmission of Zika virus had been confirmed in the Dallas area. For each woman reporting travel, a detailed travel history and review of compatible symptoms were recorded in the subsequent BPA questions.

Laboratory evaluation

Serum testing with the Food and Drug Administration–approved Zika IgM antibody capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and/or real-time reverse transcription (rRT)-polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed for all women with positive travel screens who met extant CDC criteria. Laboratory testing was performed by the Dallas County Health and Human Services (DCHHS) and the CDC. Testing was based on the time interval between last exposure (ie, last date of travel) or symptom onset and the date of screening. Serum IgM was performed by DCHHS for specimens collected >2 weeks after travel in asymptomatic and symptomatic pregnant women, up to 9 months after return from travel. Presumptive positive or equivocal serum IgM specimens were forwarded by DCHHS to the CDC for confirmatory plaque reduction neutralization (PRNT) testing. Serum rRT-PCR for Zika virus RNA was performed by DCHHS on any specimen collected within 4 weeks of symptom onset or within 6 weeks of return from travel. Serum screening alone was implemented at our institution prior to the development of CDC guidelines regarding urine testing. In August 2016, following release of the interim guidance for urine testing and evaluation of pregnant women, we implemented rRT-PCR testing of subsequent urine specimens for pregnant women with presumptive positive or equivocal serum IgM.

Ultrasound evaluation

Detailed fetal anatomic survey was performed for all at-risk women, with assessment for specific findings such as intracranial calcifications, microcephaly, ventriculomegaly, abnormal corpus callosum, cortical abnormalities, and cerebellar hypoplasia. Additional ultrasounds were performed for fetal growth assessment in women with either positive or unknown IgM results as recommended by the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Women with negative Zika virus IgM results received routine prenatal care. Women with presumptive positive or equivocal serum IgM results or with abnormal fetal ultrasound findings suggestive of intrauterine infection were referred to a dedicated maternal-fetal medicine clinic. The clinic is staffed by fellows and faculty from the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center with expertise in infectious disease affecting pregnancy. When intrauterine infection was suspected, further evaluation was conducted, including amniocentesis when indicated. Women received comprehensive counseling regarding laboratory testing, ultrasound results, the need for evaluation at the time of delivery, and the plan for postnatal follow-up in this clinic.

Infant evaluation

At the time of delivery, maternal and neonatal specimens were sent to the local health department for women with known or suspected recent Zika infection, and for those at risk for Zika infection without prior screening results. Placental and umbilical cord tissue samples were sent to CDC for rRT-PCR testing for Zika virus RNA. Umbilical cord blood was routinely sampled at delivery until late July 2016, when the CDC guidelines for evaluation of infants at risk for congenital Zika infection changed to recommend infant serum collected within the first 2 days after birth.

The scope of neonatal evaluation evolved during the study period. Initially, the CDC recommended testing only infants born with microcephaly or intracranial calcifications, or those born to mothers with positive or inconclusive Zika testing results. For these infants, PCR and serologic testing of umbilical cord blood or infant serum collected within 2 days of birth was recommended. Routine care was recommended for infants with normal prenatal imaging and postnatal physical examinations born to at-risk mothers for whom Zika virus testing was not performed. In July 2016, Zika testing on umbilical cord blood was no longer recommended by the CDC. This change was implemented in our hospital the same month. In August 2016, CDC recommended that for infants with normal prenatal imaging and postnatal physical examinations born to at-risk women not previously tested, evaluation should begin with maternal Zika testing, with subsequent infant testing if maternal results were positive or indeterminate.

Comprehensive physical exam and standard newborn hearing screen using auditory brainstem response testing were routinely performed on all infants soon after birth regardless of Zika results. Head circumference and gestational age-specific head circumference percentile for each infant was assessed using the gender-specific growth curves developed and validated by Olsen et al and currently in use at Parkland Hospital. Microcephaly was defined as head circumference <3rd percentile for gestational age.

Additional neonatal evaluation for possible congenital Zika virus infection was performed on a case-by-case basis according to evolving CDC guidelines, including urine testing, head ultrasound, and complete ophthalmologic assessment. For infants with abnormal findings, evaluation was conducted for other intrauterine infections, such as cytomegalovirus (CMV), toxoplasmosis, syphilis, or rubella virus, as appropriate.

Beginning September 2016, infants born to women with evidence of Zika virus infection during pregnancy were assigned to follow-up after delivery with both a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Children’s Medical Center Dallas, and a pediatric primary care provider. Developmental testing and infant follow-up was planned for these infants according to CDC guidelines.

Delivery outcomes and statistical analysis

Demographics and perinatal outcomes of delivered women were linked to an existing obstetric database. The database contained maternal and infant outcomes for all women delivered at Parkland Hospital. Categorical and continuous variables were compared among women with positive and negative Zika results using χ 2 and Student t tests, respectively, and P < .05 was considered significant for all analyses. Statistical analysis was performed using software (SAS 9.3; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). This study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

Results

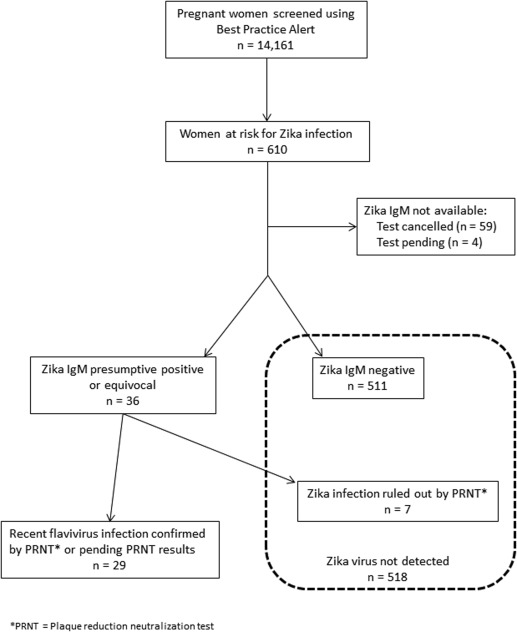

Between March 14 and Oct. 1, 2016, a total of 14,161 pregnant women were screened with the BPA ( Figure 1 ). A total of 610 (4.3%) women reported travel to a Zika-affected country and were screened with serum testing. Of these, the majority (510 [84%]) of at-risk women were identified through the prenatal clinic BPA. An additional 100 (16%) women, including those not enrolled in prenatal care or those who traveled subsequent to initial screening, were identified through direct questioning on the labor and delivery or maternal inpatient units. Of the 610 Zika tests performed, 59 (10%) were not completed due to inconsistent travel history or extant CDC guidelines. Four (0.7%) serum tests were pending at the time of submission and were excluded from the analysis. Of the 547 women with resulted Zika tests, 511 (93%) had negative Zika virus IgM results, and 36 (7%) had preliminary evidence of possible Zika virus infection. Subsequently, Zika infection was excluded in 7 women with confirmatory PRNT testing performed at the CDC leaving a total of 29 women with evidence of possible Zika virus infection during pregnancy ( Figure 1 ). Of these 29 women, only 5 reported symptoms of Zika virus disease whereas 24 (83%) were asymptomatic, which is consistent with previously published studies. Symptoms reported among our 5 pregnant patients included: rash (4/5), fever (2/5), conjunctivitis (2/5), and arthralgia (2/5).