General Pediatric Ophthalmologic Procedures

Alex V. Levin

Introduction

Physicians caring for children will be confronted with a number of ocular problems, including trauma, infection, inflammation, and ocular manifestations of systemic disease. Although management of some ocular conditions will require consultation by an ophthalmologist, initial diagnosis and management can be greatly facilitated by a familiarity with basic ocular procedures that lie within the skills of pediatricians and emergency physicians (1,2,3,4).

Opening the Lids

One of the most challenging procedures is to adequately visualize the external ocular structures when obscured by lid swelling or when a noncompliant, fearful child refuses to voluntarily allow the eyelids to be opened. Selection of the appropriate technique depends on circumstance and equipment availability. Once the eyeball is visualized, the examiner then can make the appropriate triage decision: ophthalmology consultation (hyphema, full thickness or lid margin laceration, corneal ulcer, corneal/scleral laceration), treatment (bacterial conjunctivitis, corneal abrasion), or observation (viral conjunctivitis). The eye can be evaluated in a logical, progressive anatomical fashion, with consideration given to each structure separately and in order—eye movements, visual acuity, conjunctiva, cornea, anterior chamber, pupil, lens, optic nerve, and retina.

Anatomy and Physiology

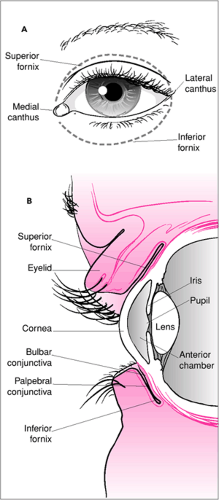

The skin of the eyelids is quite loose and redundant, which allows for the marked accumulation of fluid. As the tissues become increasingly distended, the lids become tense and more difficult to open. The eyelashes are inserted in the lid margin at the edge of each lid. The lid margin acts as a focal point for the application of mechanical devices designed to separate the lids for visualization of the underlying eyeball (Fig. 45.1). Forced lid closure is largely accomplished by contraction of the orbicularis oculi muscle. If the examiner places pressure on the bony insertions of this muscle, its contractile force is greatly disadvantaged.

Manual Lid Opening

Indications

This technique is best used for the noncompliant child who is firmly squeezing the eyelids closed. It also can be used to facilitate the instillation of eye drops or ointments. This procedure also can be used in any type of lid swelling, including trauma, as it allows for the lids to be opened without putting undue pressure on the globe.

Equipment

None.

Procedure

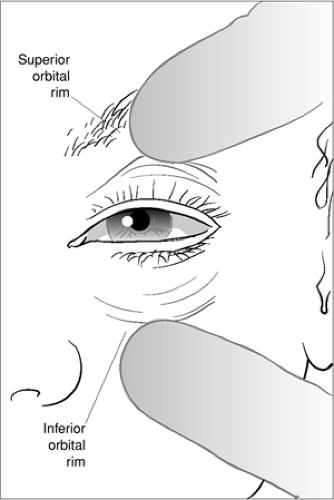

With the child’s head gently restrained in the supine position (or in an examining chair with the head tilted back), the thumb of one hand is placed on the supraorbital rim (eyebrow), and the fingers or thumb of the other hand on the infraorbital rim. Pressure is applied at these two locations compressing the underlying muscle firmly against the bone (Fig. 45.2). This is not a painful procedure. While pressure is being applied, the thumbs and underlying tissue are moved superiorly (upper hand) and inferiorly (lower hand), thus dragging the lids open. The thumbs or fingers should not be placed on the eyelids, as this may cause lid eversion or pressure on the eyeball.

Complications

The major complication of this technique is extrusion of intraocular contents if an underlying unrecognized laceration of the globe is present. This risk is reduced in the setting of trauma by selecting this procedure only for compliant children.

Lid Opening with Cotton-Tipped Swabs

Indications

Although this procedure can be very useful in opening swollen or forcibly closed lids, particularly in infants, it should not be used in the traumatized eye until the presence of a ruptured globe has been ruled out, as this procedure will put pressure on the globe.

Equipment

The examiner should use a cotton-tipped applicator of the usual bulk but with a short wooden or plastic stick handle. If only applicators with long sticks are available, then the examiner should either break the stick to within a few inches of the tip or be sure to grasp the stick close to the tip. This helps to avoid potentially harmful breakage of the stick during the procedure.

Procedure

While standing beside the supine patient’s head, ipsilateral to the eye to be examined, and with the child’s head gently restrained, one applicator tip is placed on the midbody of the upper lid, and the other in a similar position on the lower lid (Fig. 45.3A). With just enough pressure to engage the skin, the swabs are rotated (i.e., twirled) approximately one-quarter to one-half turn in the direction of the lashes (Fig. 45.3B). This will begin to draw the lid margins apart. The tips are then depressed with some firmness posteriorly (towards the underlying eyeball), engaging the entire thickness of the lid, and simultaneously the swabs are separated from each other in the direction of the orbital rims—the upper lid swab moving superiorly and the lower swab inferiorly (Fig. 45.3C).

Complications

If the swabs are not applied firmly to the lids or if the rotation is in the wrong direction, the lids will evert, thus making visualization even more difficult. If the swab sticks are too long, they may break during the procedure, possibly causing injury to the globe. Rolling the swabs too far toward the eyelid margin might allow the swabs to roll onto the corneal surface and can result in a corneal abrasion.

Summary

Using cotton-tipped swabs allows for wide, controlled separation of the lids. Swabs should not be used in the traumatized eye until rupture of the globe has been excluded.

Lid Specula

Indications

Virtually no contraindications to speculum insertion exist. Specula do not put pressure on the globe and can therefore be used to open lids swollen by trauma. They are also useful in noncompliant children with voluntary forced lid closure, provided the child is not old enough to generate more force than the speculum can apply. A speculum can be used to open eyelids that are swollen or otherwise involuntarily closed for virtually any reason.

Equipment

A variety of pediatric lid specula are commercially available. When purchasing a speculum, considerations should include tensile strength (to resist spontaneous extrusion with the child’s voluntary forced lid closure), size (to allow easy insertion, particularly in infants), cost, and ease of handling. The Alfonso eye speculum is useful in the greatest number of

situations because it has good tensile strength, a small open blade that can be inserted into palpebral openings of virtually any size, reasonable cost, and a thumb rest to facilitate ease of handling. Specula that are bulky or that require screw mechanisms to keep them in place are usually not desirable in the emergency setting and require more skill to insert. Specula and retractors should be sterilized between patients.

situations because it has good tensile strength, a small open blade that can be inserted into palpebral openings of virtually any size, reasonable cost, and a thumb rest to facilitate ease of handling. Specula that are bulky or that require screw mechanisms to keep them in place are usually not desirable in the emergency setting and require more skill to insert. Specula and retractors should be sterilized between patients.

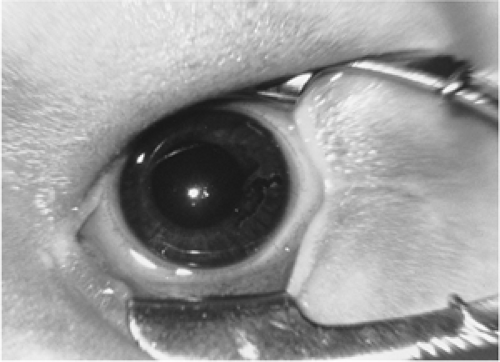

Procedure

Before inserting the speculum, the child should be supine and gently restrained to prevent spontaneous movement of the head. A drop of topical anesthetic (proparacaine or tetracaine) must be instilled. Onset of action of these drugs is within 30seconds. Arms of the speculum are grasped between the thumb and forefinger. The first blade can be inserted onto the margin of either the upper or lower lid. The examiner should gently retract the lid away from its fellow lid to expose the lid margin so that the corresponding speculum blade can be placed on the lid margin (Fig. 45.4). The speculum is then compressed closed while the engaged lid is pushed away so that the fellow lid can be engaged with the remaining speculum blade on its lid margin. The speculum is then slowly and gently released to allow the lids to separate with it.

Complications

Although specula are fashioned in such a way that, with the assistance of the normally present corneal tear film, they glide easily over the ocular surface, they may on rare occasion induce corneal abrasion. Despite the use of topical anesthetic, some patients object to the periocular “stretching” sensation, which might in turn increase agitation and combative behavior. Specula also may cause the extension of a pre-existing lid laceration.

Summary

Specula can be expensive but provide an easy and effective way to achieve lid separation. They can be used in any situation to facilitate examination of the eyeball.

Lid Retractors

Indications

Retractors can be used in virtually any situation where the lids need to be separated in an assisted fashion. They tend to be less disturbing to the agitated patient than specula, as they cause less stretching discomfort.

Equipment

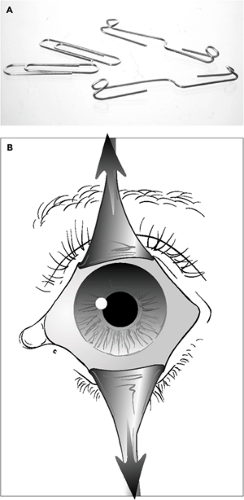

Lid retractors operate on only one lid at a time, although two can be used simultaneously to retract both lids. The most commonly used commercial type is the Desmarres retractor, which is available in a number of sizes. A small (size 1) Desmarres is perhaps most practical in the pediatric emergency setting because it can be used on any size patient. If this commercial retractor is too costly or not available, the examiner can easily construct a disposable retractor out of paper clips (Fig. 45.5A). The paper clip type chosen for this usage should be smooth metal and not coated. The coating on some clips may fragment when the clip is bent, creating particles that can disperse onto the conjunctiva or cornea. After bending, it would be prudent to double-check the bent clip to be certain no such particles have formed. Such paper clip retractors are intended for single usage and should be prepared by cleansing with an alcohol swab prior to use. Like specula, retractors do not put pressure on the globe.

Procedure

The patient is positioned and the eye anesthetized topically in the same fashion as just described for using specula. The retractor can be held with the thumb and forefinger, approaching one lid (usually the upper) at a 90-degree angle to the lid margin. The margin is then engaged by the retractor blade and pulled back away from the fellow lid while care is taken not to lift the lid too far off the surface of the eyeball (Fig. 45.5B). If needed, it can be helpful to have an assistant hold the retractor in place while the eyeball is examined. If paper clips are used as retractors, they can be taped to the forehead (upper lid) and infraorbital region (lower lid).

Complications

Like specula, retractors can result in corneal abrasion or extension of a pre-existing lid laceration. Paper clip retractors may

allow for the deposition of tiny particulate matter loosened from the clip surface when it is bent into position.

allow for the deposition of tiny particulate matter loosened from the clip surface when it is bent into position.

Summary

Retractors offer the examiner a handy, comfortable way to move the lids apart. When used properly, retractors are safe even in the setting of eye trauma.

Everting the Upper Eyelid

Introduction

This is a basic technique that should be mastered by all primary care physicians and emergency personnel. It allows for rapid inspection of the undersurface of the upper lid with minimal discomfort.

Anatomy and Physiology

The upper lid contains a band of dense collagenous tissue (tarsal plate) that spans the majority of the horizontal width of the lid and rises to occupy approximately 60% of the lid height from the lid margin upward. If pressure is applied to the lid just above the superior border of this plate, a fulcrum point is created whereby the lower section of the lid can be rotated upward, thus folding the lid back on itself so that its undersurface (the palpebral conjunctiva) comes into view.

Indications

Eversion of the eyelid is useful when the examiner wishes to view the palpebral conjunctiva of the upper lid. The lid is everted to search for foreign bodies, to facilitate complete lavage following chemical exposure, and to visualize changes diagnostic of various types of conjunctivitis.

Procedure

The key to success when performing upper lid eversion is to have the child keep the eyes in downward gaze (Fig. 45.6A). Repetitively reminding the child to keep looking down throughout the procedure is very helpful. The procedure is extremely difficult in the noncompliant child who is crying or refusing to open the eyes. Examination with sedation or ophthalmology consultation may be required. In the compliant patient, the lid can be everted with the patient supine, cradled in the arms of the parent, or sitting.

A cotton-tipped applicator (vide supra) is placed on the midbody of the upper lid with just enough pressure to engage the skin (Fig. 45.6B). The applicator is rotated toward the lid margin with just enough pressure against the eyelid skin to draw the skin up under the applicator, causing the lid margin and lashes to rotate away from the eyeball (Fig. 45.6C). The lashes or the full thickness lid margin are grasped between the thumb and forefinger and then simultaneously pulled upward (toward the forehead) while applicator tip is pushed into the body of the lid in a downward direction: the lid margin and the swab are moving in directly opposite but parallel directions (Fig. 45.6D,E). The lower half of the lid should abruptly “flip” over the swab. The examiner can then use the thumb of the hand holding the lashes to pin the lashes against the superior orbital rim or eyebrow while the examination is conducted (Fig. 45.6F). At this point, the swab is removed by

pulling it straight out laterally away from the face. Removal of the swab may require a firm tug.

pulling it straight out laterally away from the face. Removal of the swab may require a firm tug.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree