Gender Identity and Sexual Behavior

Kenneth J. Zucker

GENDER IDENTITY

Gender identity has both a cognitive component and an affective component. There is now considerable evidence that by the age of 2 to 4 years, children have a rudimentary cognitive understanding of their gender identity. They are, for example, able to self-label as a boy or as a girl. Although it is normative for children in this age range to self-label correctly, a more sophisticated cognitive understanding of gender is lacking. A girl, for example, who can correctly self-label as a girl might readily declare that she will be a daddy (or even a giraffe) when she grows up. With cognitive maturity, however, children eventually master the notion that gender is an invariant part of the self. Coinciding with a cognitive-developmental understanding of gender, there is a corresponding affective pride in gender identity self-labeling in that children appear to value themselves as being a boy or being a girl, and there is a tendency to overvalue other members of one’s sex and devalue members of the other sex—a type of “in-group vs out-group bias.”1,2

Early in development, it is common for children to hold rather stereotyped views about behaviors that are “appropriate” for boys and for girls. Some theorists argue that this is related to the tight connection that children make between subjective gender identity and surface-related gender role behaviors. Thus, young children will adhere to the notion that “only girls” can wear dresses (dubbed the “pink frilly dresses” phase3) or that “only boys” can become doctors. Over time, greater cognitive flexibility in gender role attributions emerge, although affective behavior preferences might remain strong for culturally defined gender role behaviors.1

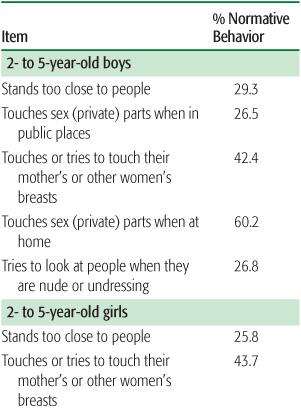

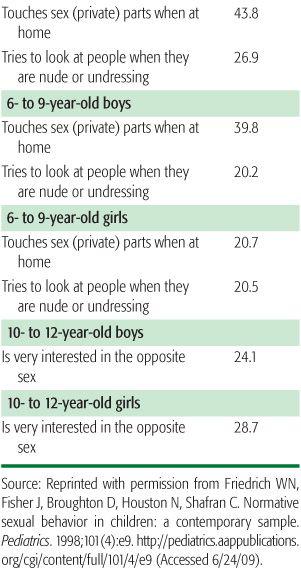

The pediatrician is often the first professional that parents might consult regarding the child whose behavior departs from conventional patterns of sex-typed behavior. Developmentally related sexual behaviors emerge at various ages in young boys and girls (Table 90-1). Issues surrounding gender often cause intense anxiety for parents. Are the behaviors in question “only a phase” that the child will outgrow? Or, are the behaviors in question prognostic of longer-term developmental issues? Regarding gender development, parents often want to know if the behaviors of their young child are prognostic of a later homosexual sexual orientation or of transsexualism, the desire to receive contrasex hormonal treatment and physical sex change (eg, in males, penectomy/castration and the surgical creation of a neovagina; in females, mastectomy and the surgical creation of a neophallus). Parents also often worry about the stigma that their child’s pervasive cross-gender behavior might elicit within the peer group and in society at large.

Table 90-1. Developmentally Related Sexual Behaviors

These kinds of questions require a familiarity about the basic mechanisms that underline gender development, which allows the pediatrician to make decisions about differential diagnosis and to consider therapeutic options. A guiding principle is that typical and atypical development are two sides of the same coin: Understanding one side informs an understanding of the other.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) contains the diagnosis gender identity disorder (GID), with distinct criteria sets for children vs. adolescents/adults (Table 90-2).4 The use of the DSM diagnosis for GID can be helpful in differentiating a gender identity problem from more transient cross-gender behavior patterns, what some clinicians term “gender variance” or “gender nonconforming” behaviors.

The DSM criteria emphasize a pattern of pervasive cross-gender behavior and associated distress with being a boy or being a girl. In a clinical practice with young children, it is probably best to first review with parents (in the child’s absence) the indicators of the GID diagnosis. If warranted, the primary care clinician can refer the parents and child for a more comprehensive psychologic/psychiatric evaluation.5 To assist pediatricians in this process, the brief Gender Identity Interview (GII) for Children (Table 90-3) is useful, especially if good rapport can be established with the child.6 The information revealed in this interview may be followed by a consultation with a specialist.

In terms of a differential diagnostic workup, parents commonly ask if there are physical or laboratory tests that can detect an underlying biologic or somatic abnormality. For children who meet the diagnostic criteria for GID, it is rarely the case that there is a co-occurring disorder of sex development (a physical intersex condition): Disorder of sex development is almost always identified during the neonatal or infancy period.7 Thus, it would be highly uncommon to detect abnormal sex chromosomes, and hormonal testing is likely to be noncontributory because circulating sex hormones are so low during early childhood prior to the onset of puberty.

Psychoeducation is an important part of the assessment process. Follow-up studies of children with gender identity disorder (GID) show that a minority will persist into adolescence or adulthood, but for the majority, GID will remit over time.8-10 The most common long-term outcome for boys with GID is the development of a homosexual or gay sexual orientation without co-occurring gender dysphoria (the subjective sense of unhappiness in being a male or a female). For girls with GID, follow-up studies suggest a more variable picture with regard to sexual orientation, but again without co-occurring gender dysphoria.

Table 90-2. DSM-IV-TR Diagnostic Criteria for Gender Identity Disorder

A. A strong and persistent cross-gender identification (not merely a desire for any perceived cultural advantages of being the other sex). |

|

1. Repeatedly stated desire to be, or insistence that he or she is, the other sex |

2. In boys, preference for cross-dressing or simulating female attire; in girls, insistence on wearing only stereotypical masculine clothing |

3. Strong and persistent preferences for cross-sex roles in make-believe play or persistent fantasies of being the other sex |

4. Intense desire to participate in the stereotypical games and pastimes of the other sex |

5. Strong preference for playmates of the other sex |

In adolescents, the disturbance is manifested by symptoms such as a stated desire to be the other sex, frequent passing as the other sex, desire to live or be treated as the other sex, or the conviction that he or she has the typical feelings and reactions of the other sex. |

B. Persistent discomfort with his or her sex or sense of inappropriateness in the gender role of that sex. |

In children, the disturbance is manifested by any of the following: in boys, assertion that his penis or testes are disgusting or will disappear or assertion that it would be better not to have a penis, or aversion toward rough-and-tumble play and rejection of male stereotypical toys, games, and activities; in girls, rejection of urinating in a sitting position, assertion that she has or will grow a penis, or assertion that she does not want to grow breasts or menstruate, or marked aversion toward normative feminine clothing. |

In adolescents, the disturbance is manifested by symptoms such as preoccupation with getting rid of primary and secondary sex characteristics (eg, request for hormones, surgery, or other procedures to physically alter sexual characteristics to simulate the other sex) or belief that he or she was born the wrong sex. |

C. The disturbance is not concurrent with a physical intersex condition. |

D. The disturbance causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. |

Specify if (for sexually mature individuals): |

Sexually attracted to males |

Sexually attracted to females |

Sexually attracted to both |

Sexually attracted to neither |