Gastrointestinal Bleeding

EPIDEMIOLOGY

In the population of healthy neonates, the incidence of upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is uncommon but not rare. A case cohort series of 5180 infants indicated that approximately 1.2% of healthy infants experienced upper GI bleeding that was brought to medical attention.1 Incidence is likely increased in populations of more acutely sick neonates, such as those in the intensive care unit; however, the exact incidence is unknown, as some may have a high prevalence of asymptomatic gastritis.2 In the pediatric intensive care population, studies have shown that patients who receive acid-blocking prophylaxis have a lower incidence of upper GI bleeding,3 but a similar study was not found in the neonatal intensive care population.

The incidence of lower GI bleeding in the healthy neonatal population is unknown. One study in the tertiary emergency room setting had an incidence of 0.3% of all pediatric visits (n = 104), where the chief complaint was rectal bleeding. Of these, half of the patients were younger than 1 year old, and the most common diagnoses were allergic colitis and anorectal fissure.4 In the neonatal intensive care unit population, serious pathology such as neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) and milk protein allergy has a higher prevalence than in the general population.4

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The differential diagnosis, assessment, and treatment of GI bleeding in neonates, as in older children and adults, depend on identifying the location of the bleed. In neonates, it may be difficult to differentiate between upper tract and lower tract bleeding, as upper GI bleeding may be brisk and manifest as hematochezia due to the rapid intestinal transit time in infants.

The following are definitions used in this chapter:

• Upper GI bleeding: bleeding arising proximal to the ligament of Treitz

• Lower GI bleeding: bleeding distal to the ligament of Treitz

• Hematemesis: Vomiting of blood, which may be obviously red or the color of coffee grounds (Table 38-1)

• Hematochezia: Passage of fresh red blood per anus, usually in or with stools (Table 38-2)

• Melena: Passage of dark, tarry stools

Table 38-1 Neonatal Differential Diagnosis for Hematemesisa

Swallowed maternal blood

Stress ulcer

Gastritis

Duplication cyst

Vascular malformation

Vitamin K deficiency

Hemophilia

Maternal idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura

Maternal nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Trauma (nasogastric tube, nasal suction)

aAdapted from Friedlander and Mamula.5

Table 38-2 Neonatal Differential Diagnosis for Hematocheziaa

Swallowed maternal blood

Dietary protein intolerance

Infectious colitis

Necrotizing enterocolitis

Hirschsprung disease and enterocolitis

Duplication cyst

Vascular malformation

Hemophilia

Maternal idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura

Maternal nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Anal fissure

Intussusception

aAdapted from Friedlander and Mamula.5

Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding

In healthy neonates, the most common causes of upper GI bleeding are swallowed maternal blood or a Mallory-Weiss tear secondary to persistent vomiting. In tertiary care settings where infants may be more ill, other common causes of upper GI bleeding include gastric or duodenal ulcers, esophagogastroduodenitis, bleeding disorders, and nasogastric tube (NGT) trauma.

Maternal Blood

Swallowed maternal blood associated with childbirth usually manifests within the first few days of birth. There is a greater incidence in neonates delivered by cesarean section. Other sources of swallowed maternal blood may be from a maternal nipple fissure in a breast-fed baby. Typically, the baby is well appearing without any other signs of distress.

Ulcers and Gastritis

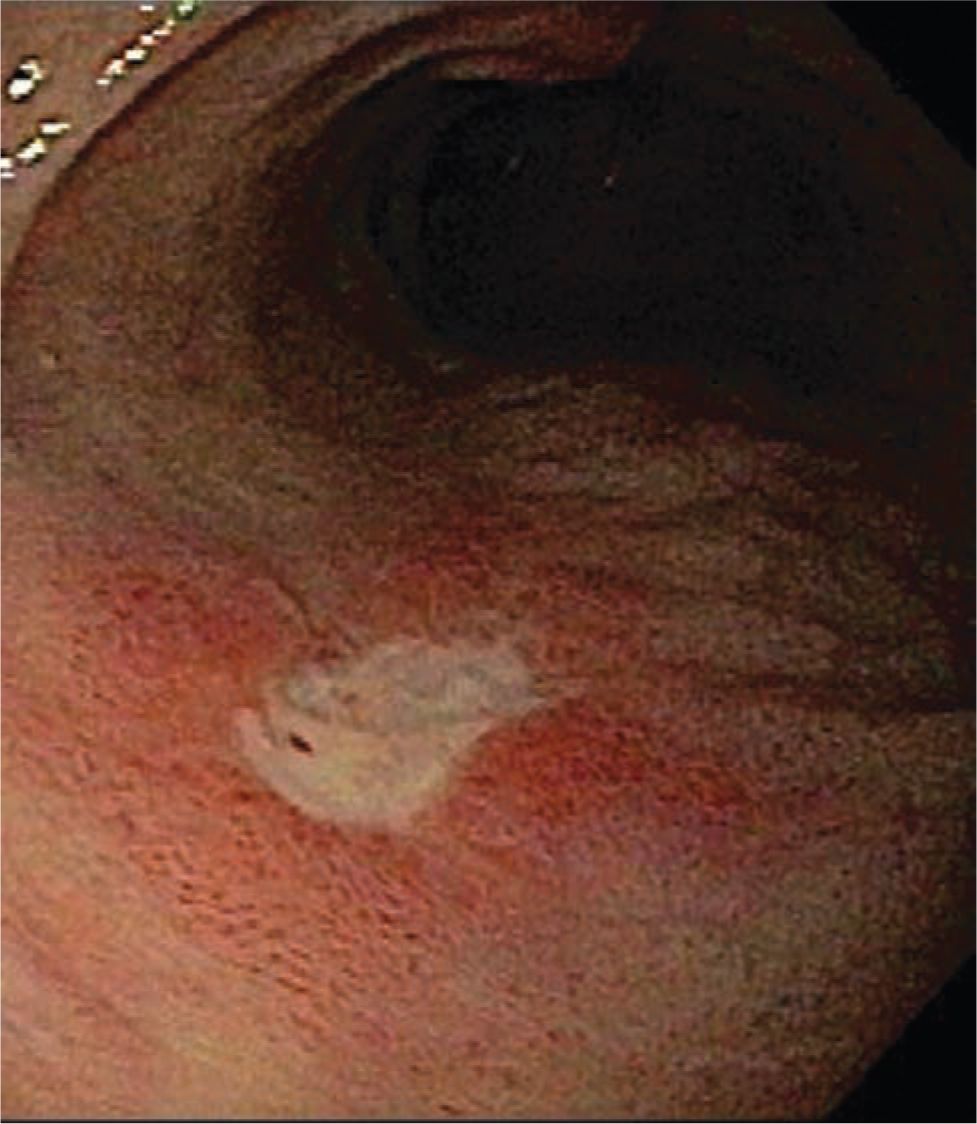

Gastric acid secretion begins shortly after birth, and this can cause ulcers or gastritis. Risk factors include stressed preterm babies in the critical care setting, mechanical ventilation, no or short duration of enteral nutrition, and medication administration6 (Figure 38-1). Medications such as indomethacin, sulindac, tolazoline, and α-adrenergic agonists have been implicated, as well as maternal aspirin ingestion.6–10 NGT trauma from forceful insertion or improper tube size or continuous suction resulting in a suction blister can also cause gastric irritation and bleeding.

FIGURE 38-1 Duodenal ulcer.

Infection with Helicobacter pylori causes gastric inflammation and is associated with causing duodenal and gastric ulcers. The prevalence of H. pylori infection is much lower in developed countries than in developing countries. Although H. pylori infection is exceedingly rare in neonates in the United States, cross-sectional studies of disease prevalence in preschool children in the United States and Europe indicated prevalence ranging from 7% to 13%, with 60% at 60 years of age.11 Ulcer disease from H. pylori is rare in children but has been reported to cause hematemesis.12

Bleeding Disorders

Hemorrhagic disease of the newborn from a deficiency in vitamin K may result in coagulopathy, especially in a patient who did not receive vitamin K at birth. Other causes of coagulopathy, such as maternal idiopathic thrombocytopenia purpura, neonatal thrombocytopenia, or congenital hemophilia, may also predispose the baby to increased bleeding risk. Significant renal failure may also cause platelet dysfunction from an acquired qualitative platelet defect, which may be treated best by dialysis but can also be remedied by desamino-D-arginine vasopressin (DDAVP)13 (see chapter 33 for information on neonatal bleeding disorders).

Varices and Portal Hypertension

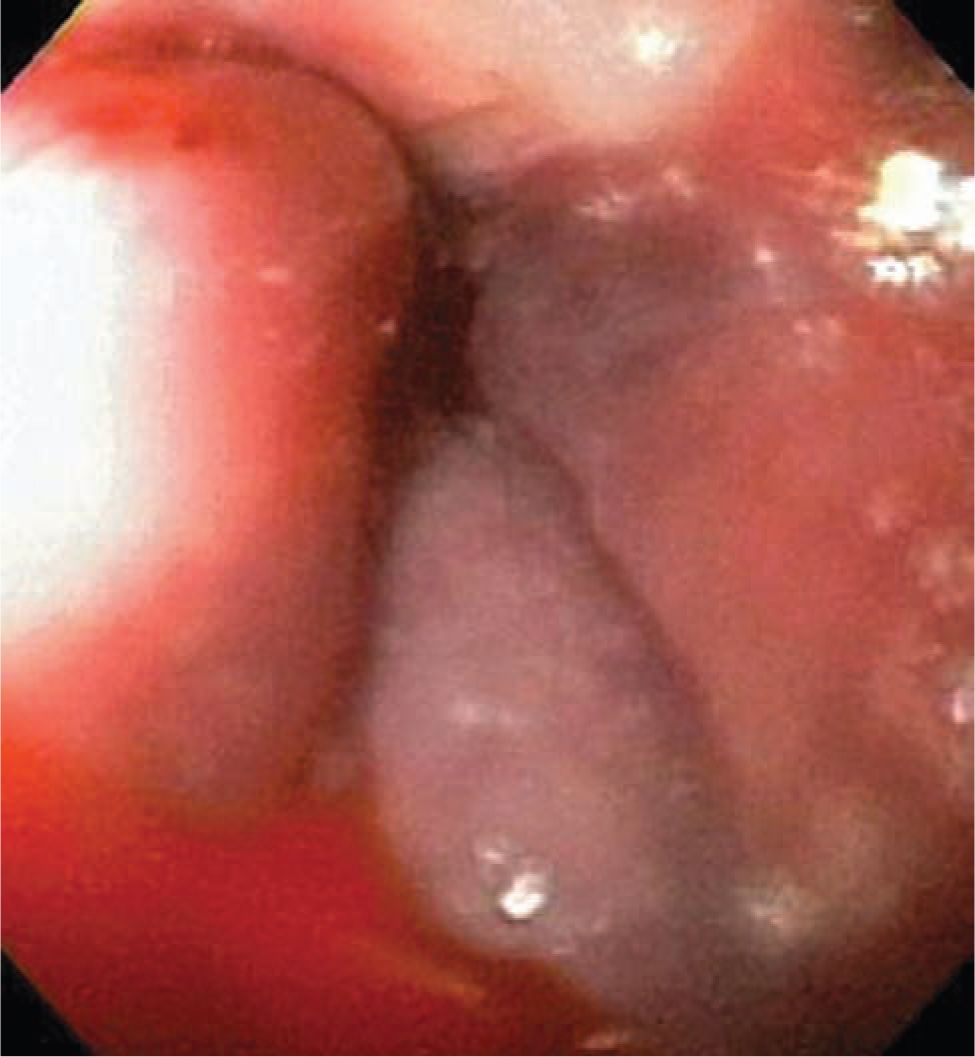

Portal hypertension from extrahepatic vascular disease or intrinsic liver disease is defined as elevated blood pressure above 5 mm Hg in the portal vein and its tributaries. Varices develop as the blood flow from the splanchnic system finds alternative pathways of portosystemic shunts back to the systemic system. Given the high blood flow and pressure in this system and the increased wall tension in the varices and abnormal blood vessel wall integrity, the rate of hemorrhage from variceal bleeding can be extremely brisk and life threatening. Varices may occur in the esophagus (Figure 38-2), stomach, or duodenum, though most sites of variceal bleeding originate from esophageal varices.

FIGURE 38-2 Esophageal varix.

Extrahepatic vascular causes of portal hypertension include portal vein thrombosis and neonatal umbilical disorders. The most frequently reported risk factors for developing portal vein thrombosis in infancy and early childhood include intra-abdominal infections due to umbilical vein catheterization, neonatal omphalitis, and congenital malformations.14,15 Intrinsic liver diseases in infancy, such as cirrhosis from biliary atresia, hemochromatosis, and parenteral nutrition-induced liver disease, cause liver fibrosis and portal hypertension (see chapter 40 on congenital liver failure and neonatal hepatitis).

Obstructing Lesions and Mallory-Weiss Tears

Obstructing lesions such as pyloric stenosis, duodenal webs, and antral webs may cause vomiting significant enough to cause esophagitis and hematemesis. Mallory-Weiss tears, defined as a tear in the gastroesophageal mucosa, may be secondary to persistent emesis in infants.16 Obstructing lesions should be considered when the patient has persistent and forceful emesis.17 Intrinsic intestinal lesions (webs, stenosis, atresia, or duplication) and extrinsic lesions (annular pancreas or malrotation with congenital bands) mostly present in the first 24 hours of life with vomiting (66% bilious), weight loss, abdominal distension, and dehydration.18 Pyloric stenosis typically presents at 3–4 weeks of age with poor weight gain, projectile vomiting, and electrolyte imbalances.

Other Causes

Allergic enteropathy can also present as hematemesis, but this is often also associated with mucoid bloody stools and allergic colitis.19,20 Similarly, NEC (see chapter 37) often presents with blood in stool but may also manifest as an ileus with associated hematemesis.

Vascular malformations: Although rare, isolated cavernous hemangiomas of the stomach have been reported to cause extensive upper GI bleeding in infants and young children.21–23 Arteriovascular malformations (AVMs) associated with blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome,24 and Osler-Rendu-Weber syndrome25–27 also may cause upper GI bleeding.

Gastric teratoma: Although gastric teratomas are extremely rare in infants and children, with only 51 cases reported in the literature, they can manifest as upper GI bleeding. On plain film radiographs, they appear as a calcified intra-abdominal mass, most often arising from the greater curvature of the stomach. This benign condition is treatable with surgical resection.28,29

Dieulafoy lesion: A Dieulafoy lesion is a large submucosal artery under the muscularis mucosa and protrudes into the gastric lumen. It appears with inflammation around the mucosal lesion. The majority of these lesions are located in the upper third of the stomach but can also be found in the small intestine. Given that the lesions are of arterial origin, they can manifest as large-volume bleeding. Reports of Dieulafoy lesions are rare in infants, but case reports cited Dieulafoy lesions in neonates as young as 1 month old.30–33

Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Anal Fissures

Anal fissures are the most common cause of rectal bleeding in the first 2 years of life. An anal fissure is a tear in the epithelium and squamous lining of the anal canal. Fissures can be classified as either acute or chronic. Acutely, the fissure may start as a simple crack in the anoderm; however, this may develop into a chronic fissure with infection and poor healing. A chronic fissure is where symptoms persist longer than 6 weeks after treatment and fibrosis is present at base of fissure. Skin tags may develop with chronic fissures. Most anal fissures are caused by constipation after the traumatic passage of a large, hard stool. Recent acute diarrhea may also irritate the epithelium sufficiently to cause a fissure. Irritation from a rectal thermometer may also cause minor bleeding. Typically, the bleeding associated with anal fissures appears as streaks of blood in the stool (not mucoid).34 A large fissure with surrounding bruising should raise concern for child abuse.

Cow’s Milk Protein Allergy/Allergic Colitis

The incidence of cow’s milk protein allergy is estimated at approximately 1%–3% of the general population.35,36 Cow’s milk protein allergy is the most common form of enterocolitis caused by food allergies and is a leading cause of rectal bleeding in healthy children second to anal fissures. In a study of infants presenting with rectal bleeding, 46% had biopsy-proven allergic colitis.37 Although it can rarely present in the first few days of life,38 it usually presents in the first few months of life. Infants with allergic colitis typically have loose stools with varying amounts of mucus and gross or occult blood and may present with failure to thrive. Carbohydrate malabsorption may also cause abdominal distension, perianal erythema, and significant diaper dermatitis. Malabsorption may also cause micronutrient deficiency in iron and zinc. Further laboratory examinations may show peripheral eosinophilia, hypoalbuminemia, and anemia. Constipation as the primary symptom has also been reported.39 Patients may also have concurrent atopic illnesses such as eczema and asthma.

Cow’s milk contains the β-lactoglobulin protein, which is absent in human milk and may contribute to the development of cow’s milk protein intolerance. Immunoglobulin (Ig) E–positive allergy responses are linked to the casein protein, and those with IgE-mediated allergy are less likely to outgrow their allergy.40,41 Endoscopic examination of the colon often shows focal erythema, erosions, and nodular lymphoid hyperplasia. Histological examination reveals infiltration of the mucosa and lamina propria with eosinophils (>6–10/high-powered field) with eosinophilic degranulation or infiltrate of the crypt and surface epithelium and nodular lymphoid hyperplasia.42

The clinical course is usually self-limited, with most children tolerating antigen reintroduction by 2–3 years of life.43,44

Necrotizing Enterocolitis

It is important to exclude NEC (see chapter 37) in any neonate presenting with hematochezia, as patients with NEC may progress to significant morbidity. NEC is inflammatory bowel necrosis of portions of the small or large intestine. It typically affects premature infants, but neonates with a history of birth asphyxia, polycythemia, transfusions, intrauterine growth restriction, maternal cocaine use, cyanotic heart disease, or sepsis may also increase the risk for bowel ischemia.9,45,46

Symptoms may initially start with feeding intolerance and small amounts of blood in the stool or residuals from nasogastric feedings. This may progress with emerging signs of systemic instability, such as apnea, bradycardia, desaturations, temperature instability, and increased gastric residuals. Physical examination may reveal signs of abdominal distension, tenderness, erythema around the abdominal wall, and decreased bowel sounds. The classic radiological finding of NEC is pneumatosis intestinalis (gas in the bowel wall). Abdominal films may also show dilated loops of bowel, bowel wall thickening, and even free air in cases of frank perforation.

Infectious Colitis

Enteroinvasive infections cause lower GI bleeding via disrupting the mucosal integrity of the bowel. Bacterial pathogens include Salmonella, Shigella,47 Campylobacter, Yersinia enterocolitica, Clostridium difficile, and Escherichia coli (in particular the O157:H7 variant). It is important to note that Clostridium difficile toxin can be found in 10%–36% of healthy neonates48 due to microbial colonization, and 71% of neonates were stool culture–positive in a study in a special care nursery setting.49 Therefore, a true C. difficile infection often requires a concomitant clinical picture of bloody diarrhea with mucus and, in the more severe forms, fever, leukocytosis, and hypoalbuminemia. Parasitic infections with Entamoeba histolytica can also cause infectious colitis. Viral infections with Cytomegalovirus (CMV) and herpes simplex virus can also cause significant lower GI hemorrhage, especially in immunodeficient patients.50

Meckel Diverticulum

Meckel diverticulum51 (MD) is the most common congenital abnormality of the small intestine, with an incidence of approximately 2% of the population. It consists of a vestigial remnant of the vitelline duct that contains heterotopic gastric mucosa (80%) or pancreatic tissue (5%). The diverticulum is usually located within 100 cm of the terminal ileum. The acid-secreting mucosa causes ulceration of the adjacent mucosa and results in painless rectal bleeding and classically currant jelly stool but also may manifest as melena, hematochezia, or even frank perforation.52

Other Causes

Hirschsprung disease with enterocolitis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree