Gastric Lavage

Mary A. Hegenbarth

Gary S. Wasserman

Introduction

Gastric lavage has been performed for almost two centuries, and it yet remains a controversial procedure. In 1812, Physick used a hollow tube to lavage twin infants with laudanum (tincture of opium) overdose (1). Determining the best approach for decontamination of the poisoned patient is a difficult task because there are many confounding variables (e.g., characteristics of the substance ingested, amount of ingestant, time since ingestion, unreliability of history, time for patient to seek medical care, and differences in techniques) (2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12). Despite the extensive use of gastric lavage, few reports have demonstrated improvement in patient outcomes (13,14,15). In recent years, the advisability of any gastric emptying procedure for most patients has been questioned, with many experts recommending activated charcoal as the primary treatment (4,5,10,12,16,17). Official position statements for gut decontamination of the poisoned patient were first published in 1997; gastric lavage guidelines were re-evaluated in 2004 and are essentially unchanged (18,19).

Since acute ingestions rarely cause fatality, especially in nonintentional childhood ingestions, practitioners must rapidly decide if gastric lavage has an acceptable risk-benefit ratio for a particular patient. Other methods of gut decontamination include activated charcoal and/or whole bowel irrigation (syrup of ipecac is no longer recommended). Consultation with a clinical toxicologist or poison center is highly recommended if the clinician is unsure about the best method of gastrointestinal decontamination for a particular patient; treatment should be individualized.

There has been a 85% decline in the utilization of gastric lavage from 1993 to 2005 (3.45% of all exposures to 0.51%) (20,21). Most pediatric patients requiring treatment for toxic ingestions are either young children less than 6 years of age with accidental poisoning or adolescents with intentional ingestions due to suicide attempts or illicit drug use. The procedure is similar to gastric intubation (Chapter 84) and is done in the hospital setting (primarily the emergency department) by physicians and/or nurses. Gastric lavage is moderately difficult to perform and requires attention to detail for optimal effectiveness and avoidance of complications. Gastric lavage should not be performed routinely in the management of the poisoned patient (19).

Anatomy and Physiology

Small children obviously have smaller nasal and oral passageways, a shorter esophagus, and a smaller stomach than adults. Other factors that may make lavage relatively difficult in young children include a large tongue, loose primary teeth, and an uncooperative attitude regarding the procedure. Lavage tubes are easily inserted too far into children, which may cause serious malposition despite clinical signs of adequate placement (22).

Proper insertion length has been found to correlate with patient height (22,23).

Proper insertion length has been found to correlate with patient height (22,23).

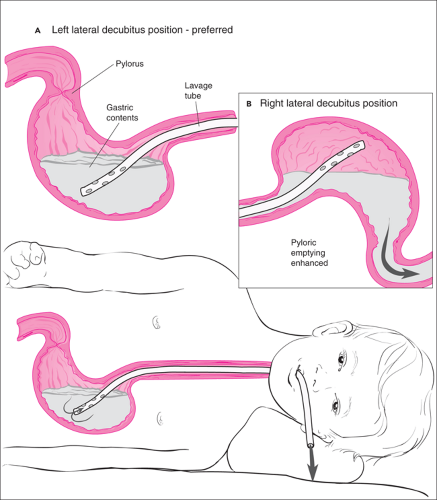

Gastric lavage aims to remove toxin from the stomach before absorption occurs; its effectiveness diminishes with increasing time since ingestion. Effectiveness also depends on the physical characteristics of the substance(s) ingested. Liquids are rapidly absorbed and are unlikely to be significantly recovered given the typical delay preceding lavage. Solid preparations are absorbed more slowly; absorption is further delayed with enteric-coated forms, substances that retard gastrointestinal motility (e.g., anticholinergic agents), and substances that tend to form concretions. Dogma suggests that gastric lavage may have the undesired effect of accelerating absorption by enhancing pyloric emptying into the duodenum (24). However, more recent studies contradict these earlier results and have discovered no evidence showing any increase in the amount of marker present in the small bowel after lavage compared with no intervention (25,26). Enhanced gastric emptying into the pylorus is more likely if the patient is lying on the right side or if large aliquots of cold fluids are used (27,28,29). Therefore, the left lateral decubitus position is preferred to maximize access of the tube to stomach contents and minimize pyloric emptying (Fig. 125.1). Young children are more susceptible to electrolyte changes than adults; normal saline or 0.45 normal saline is recommended rather than water. Using warmed or at least room temperature fluid will prevent iatrogenic hypothermia and may aid in slowing pyloric transit time (27). Gastric emptying from lavage is incomplete, as continued drug absorption occurs and drug concretions may form (14,30,31).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree