Introduction

During pregnancy, almost every organ of the mother’s body has to work harder in order to meet the demands of the developing fetus [1]. Women with chronic disease struggle to fulfill these physiologic demands. As a consequence, pregnancy outcome can be compromised and long-term maternal health may be threatened.

Gestational syndromes generally develop in the second half of pregnancy when the physiologic burden is at its greatest. For example, the progressive insulin resistance of pregnancy acts as a stress test that transiently unmasks carbohydrate intolerance which we term “gestational diabetes mellitus” in women who are predisposed to type 2 diabetes. Childbirth leads to remission, but the disease returns in later life when the effects of aging and weight gain expose a persistent vulnerability to diabetes.

In this chapter, the consequences of an adverse pregnancy outcome on a woman’s long-term health are discussed and recommendations are given that might prevent disease in later life.

During healthy pregnancy the mother is propelled into an increasingly proatherogenic metabolic state [2,3]. Shortly after conception she develops a high cardiac output [4], hypercoagulability [5] and increased inflammatory activity [6]. After 20 weeks she develops insulin resistance [3,7] and hyperlipidemia [8]. Each of these gestational changes is more pronounced in women who later develop pre-eclampsia [3–8]. This must be at least partly due to the presence of subclinical classic cardiac risk factors in “healthy” women who go on to develop pre-eclampsia [9,10]. These women are more likely to be overweight, have higher lipid levels, higher blood pressure and insulin resistance and to have a thrombophilia, compared with women who go on to have a normotensive pregnancy [9–11].

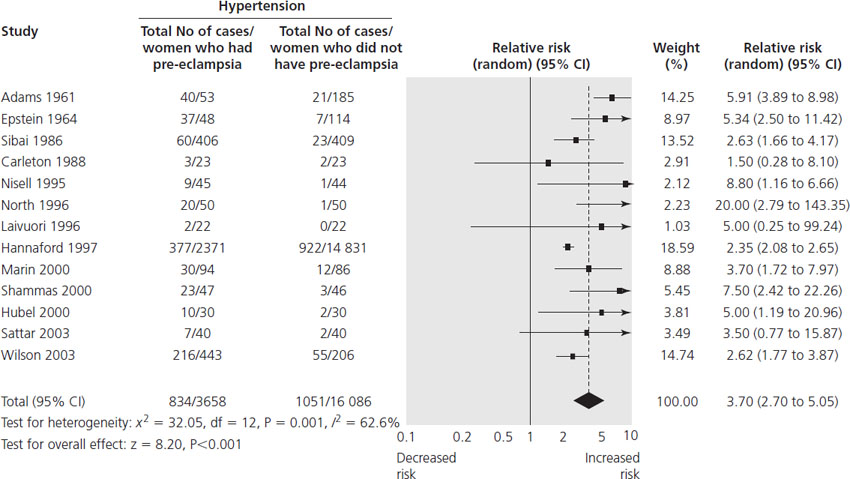

Post partum, women who have had pre-eclampsia usually recover within 3 months of delivery, but are at an increased risk of developing cardiovascular disease in later life [12]. A systematic review and meta-analysis that included over 3.5 million women showed that women who had pre-eclampsia were more than twice as likely to develop future ischemic heart disease years after the index pregnancy compared with women who had a normotensive pregnancy (Table 26.1). A similar risk exists for future cerebrovascular accident [12]. These risks appear to be mediated through an even stronger future risk of chronic hypertension after pre-eclampsia (relative risk (RR) 3.70, 95% confidence interval (CI) 2.70–5.05) [12] (Figure 26.1).

Table 26.1 The relative risk of a woman developing future disease after pre-eclampsia

| Pregnancy syndrome | Future disease | Relative risk (95% CI) |

| Pre-eclampsia | Chronic hypertension | 3.70 (2.70–5.05) |

| Pre-eclampsia | Ischemic heart disease | 2.16 (1.86–2.52) |

| Preterm pre-eclampsia | Ischemic heart disease | 7.71 (4.40–13.52) |

| Pre-eclampsia | Cerebrovascular accident | 1.81 (1.45–2.27) |

| Pre-eclampsia | Venous thromboembolism | 1.79 (1.37–2.33) |

| Pre-eclampsia in 1st pregnancy only | Endstage renal disease | 3.2 (2.2–4.9) |

| Pre-eclampsia in 1st and 2nd pregnancies | Endstage renal disease | 6.4 (3.0–13.5) |

| Pre-eclampsia in 1st, 2nd and 3rd pregnancies | Endstage renal disease | 15.5 (7.8–30.8) |

| Preterm labor | Fatal cardiovascular disease | 1.8 (1.3–2.5) |

| Pre-eclampsia, fetal growth restriction and preterm labor | Fatal cardiovascular disease | 7.0 (3.3–14.5) |

Figure 26.1 Pre-eclampsia and risk of hypertension in later life. Reproduced with permission from Bellamy et al. [12].

Women who have preterm pre-eclampsia (before 37 weeks) have a particularly high RR of death from future cardiovascular disease (RR 8.12, 95% CI 4.31–15.33) and stroke (RR 5.08, 95% CI 2.09–12.35) [13], compared with women who had a normotensive pregnancy. Recurrent pre-eclampsia, which strongly suggests chronic renovascular disease in the mother, is associated with a particularly high risk of future hypertension and kidney disease in later life [14,15].

Fortunately, cardiovascular disease is rare in young women, but its prevalence increases with age. In the UK, 8.3% of women aged 50–59 years will have a cardiovascular event over the next 10 years [16]. If a woman in this age group had a pregnancy affected by pre-eclampsia, her calculated risk of having a cardiovascular event in the next 10 years could double to 17.8%. This pushes her towards a category of risk where therapeutic prophylaxis against cardiovascular disease is recommended with low-dose aspirin and HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (“statins”).

Conversely, women who have had a normotensive, term pregnancy appear to be in a privileged position with a lower than average risk of future cardiovascular disease compared with a general population [13,15].

Preterm birth and fetal growth restriction

Women who have had a pregnancy affected by preterm birth without pre-eclampsia are also at increased risk of death from future cardiovascular disease (RR 2.95, 95% CI 2.12–4.11) [17]. Similarly, a pregnancy complicated by fetal growth restriction identifies a woman as being at increased risk for future cardiovascular disease [17]. In one population, women who had a baby weighing less than 2500 g had an 11 times greater risk of dying from future ischemic heart disease (IHD) compared with those who had a baby weighing more than 3500 g [17]. These observations suggest that a different etiology may explain preterm pre-eclampsia, which is associated with low birthweight babies, compared with late pre-eclampsia, which is often associated with high birthweight babies [18]. Women who have a pregnancy complicated by all three of pre-eclampsia, preterm labor and fetal growth restriction (FGR) have the highest risk of cardiovascular disease in later life [13,17].

It is entirely possible that a woman who has had pregnancies complicated by FGR, preterm birth and/or pre-eclampsia has some combination of inherited and acquired risk factors for future cardiovascular disease that also caused her adverse pregnancy outcomes. It is therefore possible that such a woman would face the same long-term risk of cardiovascular disease even if she had never become pregnant and that the pregnancy complication only heralds but does not cause the later cardiovascular disease.

One epidemiologic study attempted to address this issue by comparing future cardiovascular risk according to classic risk factors for heart disease with or without a pregnancy affected by FGR or pre-eclampsia [19]. Women who had a pathologic pregnancy had a greater risk of ischemic heart disease compared with those who only had a classic risk factor for heart disease. It remains unclear whether this observation reflects an additional risk because of the pregnancy or that the pregnancy unmasks an as yet unknown additional risk factor for cardiovascular disease.

Furthermore, there is an association between an increasing number of healthy pregnancies and an increased risk of ischemic heart disease [20]. Parous women without pregnancy complications have a 1.95-fold (95% CI 1.03–3.7) higher cardiovascular disease prevalence than nulliparous women. Women who have had more than five pregnancies have the greatest risk of future cardiovascular disease [20]. Whether this reflects cumulative harm done due to the repeated physiologic strain of hemodynamic and metabolic changes of pregnancy or whether it follows weight retention after each pregnancy remains unclear.

Eclampsia in a first pregnancy does not appear to be associated with the same increased risk of future hypertension as seen following pre-eclampsia [21–23]. The increased risk of future cardiovascular disease is, however, evident in multiparous women who develop eclampsia, or in primiparous women of black African origin. It is possible therefore that the pathology leading to isolated eclampsia is different from that which heralds the multiorgan syndrome of pre-eclampsia. Support for this suggestion follows the observation that women who have had eclampsia appear to be at greater risk of future epilepsy [24], in particular temporal lobe epilepsy, associated with hippocampal sclerosis. The hippocampus is supplied by the posterior circulation, which is most often compromised during eclampsia. Whether eclampsia unmasks a pre-existing vulnerability to hippocampal ischemia or causes it, is unclear.

When eclampsia occurs with pre-eclampsia, future maternal health is predicted by the gestation of onset of pre-eclampsia [25]. Women who had eclampsia before 30 weeks gestation were more than threefold more likely to develop chronic hypertension compared with those who had eclampsia after 37 weeks [25]. If the subsequent pregnancy was also complicated by pre-eclampsia then the incidence of chronic hypertension more than 7 years later has been estimated at 25%, compared with only 2% for women who had a normotensive pregnancy following their eclamptic pregnancy [25].

The consistent findings that pre-eclampsia, preterm birth and intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) are predictive of long-term maternal risk of cardiovascular disease provides an ideal opportunity for clinicians to initiate risk factor reduction in women whose pregnancies have been complicated by these conditions. Possibly helpful recommendations for these women (and for the other pregnancy complications listed below) are listed in Table 26.2. The potential importance of each of these interventions should be emphasized by the obstetrician to both the patient and the patient’s medical primary care provider.

Table 26.2 Possibly helpful interventions to decrease subsequent risk in mothers with pregnancy complications

| Pregnancy complication that points to a future health risk | Future health risk | Possibly helpful advice, counselling or screening to reduce subsequent risk |

| Patients with pre-eclampsia prior to 37 weeks, recurrent pre-eclampsia or who have delivered pre-term or growth restricted infants | Cardiovascular disease (ischemic heart disease and stroke) |

|

| Renal disease |

| |

| Thromboembolic disease | Recurrent thromboembolism |

|

| Gestational diabetes | Type 2 diabetes |

|

| Post-partum thyroiditis | Hypothyroidism |

|

| Peripartum cardiomyopathy |