ny given time. It is less known whether the resolution of UI is a direct result of effective medical and surgical intervention or due to the waxing and waning of UI in any single woman. Why would UI resolve in the absence of treatment? It may be that some modifying factor has improve]”>

Epidemiology of Urinary Incontinence

Urinary incontinence (UI) is a common problem in women that affects quality of life and results in over $16 billion in direct medical costs annually in the United States (1995 figures). UI can be surveyed by using standardized questionnaires, which have been used to estimate the prevalence of UI in the general population and in affected women seeking treatment. Unfortunately, severity of UI is not always correlated with level of bother: one woman may leak several times a day and not be bothered at all, while another would report an occasional leak as having severe impact on her quality of life. Thus, some measure of bother is considered when reporting UI.

Definitions

Rates vary in populations because of differences in definition, but good standardization with regular updates has been provided by the International Continence Society (ICS) for more than 20 years. The ICS has the following definitions for UI:

Urinary incontinence: the complaint of any involuntary urine leakage. The main types in women are stress, urge, and mixed.

Stress urinary incontinence (SUI): the complaint of involuntary leakage associated with effort or exertion or on coughing or sneezing. If the incontinence is diagnosed on urodynamic testing, this is termed urodynamic stress incontinence (USI).

Urge urinary incontinence (UUI): the complaint of involuntary loss of urine accompanied by or immediately proceeded by urgency. If the incontinence is diagnosed on urodynamic testing with increased detrusor pressures reproducing symptoms during filling, the diagnosis is detrusor overactivity with incontinence (DOI.) Because some women are bothered by frequency, nocturia, and urgency but do not actually leak urine with urge, a broader term, overactive bladder, may incorporate all of these symptoms.

Mixed incontinence: the presence of both stress and urge incontinence in the same patient.

Prevalence

The prevalence of any UI in community-dwelling women ranges from 10% to 40%; while this seems surprisingly high, women with UI often underreport or delay seeking treatment for UI for several years after the condition has become bothersome. Approximately one in four women with UI is considered to have “severe” UI: in studies that

differentiate “any” UI from “severe” UI, the prevalence is 29% (11% to 72%) versus 7% (3% to 17%), respectively. In institutional-dwelling adults, the prevalence of UI is 50% or higher. Overall, half of women with UI complain of pure SUI, 30% to 40% complain of mixed urinary incontinence (MUI), and 10% to 20% complain of pure UUI. However, these proportions vary with age: middle-age women complain of SUI, while MUI predominates in older women.

differentiate “any” UI from “severe” UI, the prevalence is 29% (11% to 72%) versus 7% (3% to 17%), respectively. In institutional-dwelling adults, the prevalence of UI is 50% or higher. Overall, half of women with UI complain of pure SUI, 30% to 40% complain of mixed urinary incontinence (MUI), and 10% to 20% complain of pure UUI. However, these proportions vary with age: middle-age women complain of SUI, while MUI predominates in older women.

Incidence and Regression

It was thought previously that UI was a progressive condition, but some recent reports have highlighted the fact that a certain number of women develop UI and a certain number resolve UI at aiv class=”TLV2″ id=”B01337156.0-2178″ id_xpath=”/CHAPTER[1]/TBD[1]/TLV1[1]/TLV2[5]”>

<DMPTYING.

Prevention

Some of the mentioned risk factors are potentially modifiable. Weight loss has been shown to reduce the severity of UI in women with BMI >30. With increasing request for cesarean delivery, more information is needed as to whether cesarean performed solely to prevent pelvic floor damage is really effective in defined patient populations. Few studies of primary prevention of UI have been undertaken, but women with a family historyctors have involved cross-sectional studies, with the best-studied factors being parity, age, and obesity. Specific risk factors for UI type are more developed for SUI (all of those mentioned), but risks for urge incontinence may include childbirth and obesity.

Pregnancy and childbirth are the most significant risk factors: half of all women experience UI increases during pregnancy, and leakage both before and during pregnancy seems to be associated with parity, age, and body mass index (BMI). Multiple studies demonstrate that episiotomy is not protective. Current epidemiologic studies suggest that cesarean delivery is somewhat but not completely protective. Although some UI resolves during the postpartum period, women who still experience UI at 3 months postpartum are likely to be incontinent 5 years later. Increasing parity and birth weight may be additive, but there is conflicting data in the literature.

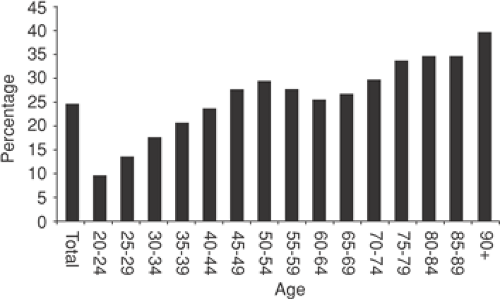

Most epidemiologic studies demonstrate that increasing age is associated with increasing UI, but surprisingly, the highest prevalence of UI peaks first at age 50 years (Fig. 51.1). SUI predominates in middle-age women, but urge incontinence increases with age. This is not to say that UI is a normal part of aging; rather, factors that contribute to UI are increased with age as well. Obesity defined as >20% over ideal weight or BMI >30 is a risk factor for both urge and stress incontinence, the mechanism in stress being increases in intra-abdominal pressure. UUI is also increased in women with obesity.

Several recent studies in differing populations indicate that family history of UI in first-degree relatives increases the risk of UI four to six times for individual women. Sexual abuse has been identified recently as an important contributor to overactive bladder symptoms.

It is less clear whether UI is affected by the menopause and hysterectomy, and there is conflicting evidence as to the role of estrogen replacement. Other risk factors include functional and cognitive impairment, constipation, smoking, and pelvic organ prolapse.

TABLE 51.1 Questionnaires for the Evaluation of Urinary Incontinence | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|