Fecal Incontinence and Defecation Disorders

Dee E. Fenner

Catherine Ann Matthews

Bowel control problems cover a broad range of symptoms and pathophysiology that encompass disorders of bowel evacuation and storage, bowel motility, anorectal pain syndromes, and anatomic abnormalities such as hemorrhoids, anal fissures, and tumors. Patients may present to the obstetrician–gynecologist with symptoms that range from excessive straining, having to support the perineum or posterior vaginal wall to defecate, or suffering from frank fecal incontinence.

Bowel and anorectal disorders are divided into two major categories: those arising from a defined structural or neuropathic defect versus a functional disorder in which no such pathology can be detected. For example, obstructed defecation may be caused by an anatomic defect of the posterior vaginal wall (rectocele or perineocele) or may result from the functional inability to voluntarily relax the muscles of the pelvic floor (pelvic floor dyssynergia). The Rome III criteria are a set of consensus agreed-on criteria that standardized definitions about functional disorders of the bowel, rectum, and anus. The broad category of functional bowel disorders includes irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), functional abdominal bloating, functional constipation, and functional diarrhea. Included in the category of functional anorectal disorders is functional fecal incontinence and functional anorectal pain syndromes including levator ani syndrome, proctalgia fugax, and pelvic floor dyssynergia. The specific diagnostic criteria for each of these functional disorders are listed in Table 54.1.

The prevalence of bowel disorders is higher in women than in men. Highly variable rates of defecatory dysfunction and fecal incontinence have been reported, which most likely reflects the heterogeneity of the populations studied, the use of nonstandardized questionnaires, a variety of definitions in terms of frequency of defecation or fecal loss, and patient reluctance to disclose these potentially embarrassing problems. Constipation, defined as less than three stools per week, affects 2% to 28% of those surveyed. Obstructed defecation occurs in approximately 7% of the adult population affected by constipation, and while many of these women demonstrate posterior vaginal wall defects radiologically, it is unclear whether this is a cause or a consequence of chronic straining.

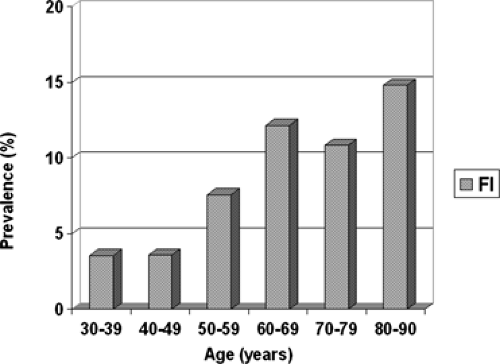

Fecal incontinence is defined as the inability to defer the elimination of liquid or solid stool until there is a socially acceptable time and place to do so. Anal incontinence includes the inability to defer the elimination of gas, which may be equally socially embarrassing. The community-based prevalence of fecal incontinence has been reported as 1.4% to 2.2%. Aging has been consistently identified as a major risk factor for the development of fecal incontinence, and the prevalence has been reported to approach 50% in nursing home residents. A recent study of more than 3,000 community-dwelling women found a population-adjusted prevalence of 7.7% when fecal incontinence was defined as loss of liquid or solid stool at least monthly. The prevalence of fecal incontinence increased linearly with age (Fig. 54.1). Significant independent risk factors included age, depression, vaginal parity, and a history of operative vaginal delivery. A recent study of the prevalence of anal incontinence in women seeking general gynecologic care suggested that the prevalence of symptoms when asked in this population is higher. In a group of 457 women seeking general gynecologic care, the overall rate of bothersome anal incontinence was 28.4%. The mean age of this cohort was 39.9 years and after logistic regression analysis, IBS (odds ratio [OR] 3.2; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.75 to 5.93), constipation (OR 2.11; CI 1.22 to 3.63), age (OR 1.05; CI 1.03 to 1.07), and higher body mass index

(OR 1.04; CI 1.01 to 1.08) remained significant risk factors. It is unclear if it was the type of questionnaire or comfort of the patients in disclosing this information to their gynecologist that resulted in such a dramatically higher affirmative response. This study certainly raises the question of anal incontinence being a silent affliction for many women.

(OR 1.04; CI 1.01 to 1.08) remained significant risk factors. It is unclear if it was the type of questionnaire or comfort of the patients in disclosing this information to their gynecologist that resulted in such a dramatically higher affirmative response. This study certainly raises the question of anal incontinence being a silent affliction for many women.

TABLE 54.1 ROME III Criteria for Functional Disorders | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||

Fecal incontinence is also significantly more common in women with other pelvic floor disorders; 7% to 30% of women with urinary incontinence and/or pelvic organ prolapse also have fecal incontinence. The presence of both urinary and fecal incontinence is known as dual or double incontinence. In a recent case-controlled study of women with and without pelvic floor disorders, those with pelvic organ prolapse and/or urinary incontinence were five times more likely to report bothersome anal incontinence than a group of healthy control women. The presence of this “double” incontinence has been associated with a significantly higher adverse effect on quality of life. It is clear that while screening for bowel problems in the general gynecologic population is important, it is imperative that any woman with pelvic floor dysfunction is comprehensively evaluated for concomitant fecal incontinence.

Many patients are reluctant to seek medical attention for bowel disorders because of embarrassment and social stigma. Primary care providers, including obstetricians and gynecologists, are therefore integral to the successful disclosure of such problems by routinely inquiring about bowel function during periodic health care visits. Ideally, a few written questions such as “Do you have difficulty emptying your bowels” and “Do you leak gas, liquid, or solid stool” should be part of the standard office intake questionnaire. Several reports have shown that twice the number of patients complain of fecal or flatal incontinence when given written questionnaires than when answering verbal

questions. If an affirmative response if obtained, then further quantification of the problem is obviously required. The Wexner fecal incontinence scale is a quick and simple questionnaire that has been validated to track changes in symptoms and is a useful tool to assess and track patient progress (Table 54.2).

questions. If an affirmative response if obtained, then further quantification of the problem is obviously required. The Wexner fecal incontinence scale is a quick and simple questionnaire that has been validated to track changes in symptoms and is a useful tool to assess and track patient progress (Table 54.2).

Because approximately 10% of women will experience some alteration in bowel habits after one vaginal delivery, it is especially critical to incorporate open-ended questions concerning flatal or fecal incontinence and fecal urgency at the 6-week postpartum visit. Other high-risk groups that should be targeted for additional questions regarding bowel storage and evacuation are women with other pelvic floor disorders and those over age 65.

A critical component of screening for anorectal disorders includes colon cancer screening. The recommended screening guidelines from the American Cancer Society are presented in Table 54.3. In general, screening guidelines are for “asymptomatic” patients and those not at an increased risk for colon cancer. First-degree relatives of patients with colon cancer or patients with acute changes in bowel habits, including gross or occult blood, should be referred to a gastroenterologist or surgeon for colonoscopy and other evaluation.

TABLE 54.2 Wexner Scale for Anal Incontinence, a Validated Instrument to Quantify the Type and Severity of Incontinence | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Anatomy

The anorectum comprises the distal-most portion of the gastrointestinal tract. The rectum is a hollow muscular tube, 12 to 15 cm long, composed of a continuous layer of longitudinal smooth muscle that interlaces with the underlying circular smooth muscle. It is separated from the anus by the dentate, or pectineal line that demarcates a transition in the type of epithelium and innervation. The rectum is lined by columnar epithelium and is under autonomic control. In contrast, stratified squamous epithelium, innervated by the somatic nervous system, is found in the anal canal.

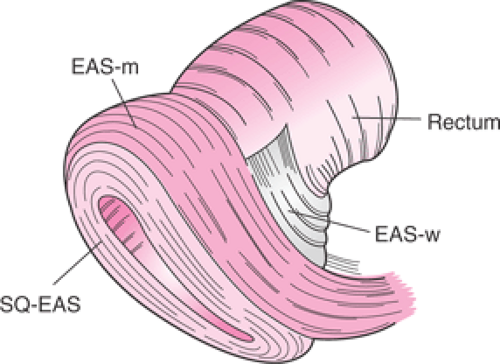

The anal sphincter complex is made up of the internal anal sphincter (IAS) and external anal sphincter (EAS), which provide both resting and increased voluntary tone to the anal canal. The IAS is a thickened expansion of the circular smooth muscle of the bowel wall, a predominantly slow-twitch, fatigue-resistant muscle that contributes approximately 70% to 75% of the resting sphincter pressure but only 40% after sudden rectal distension and 65% during constant rectal distension. The anus is therefore normally closed by the tonic activity of the IAS that is primarily responsible for maintaining anal continence at rest. This barrier is reinforced during voluntary squeeze by the EAS. The anal mucosal folds, together with the expansive anal vascular cushions, provide a tight seal. These barriers are further augmented by the puborectalis muscle, which when tonically contracted forms a flaplike valve that creates a forward pull and reinforces the anorectal angle. Figure 54.2 demonstrates a simplified drawing of the sphincter complex.

Through voluntary contraction, the EAS can contribute an additional 25% of anal squeeze pressure. Because the

EAS is made up of fast-twitch, fatigable fibers, this increased tone cannot be maintained over a prolonged period. The EAS is integral to maintaining voluntary control over the evacuation of gas and liquid stool. The pudendal nerve, which arises from the second, third, and fourth sacral nerves, innervates the EAS. A pudendal nerve block creates a loss of sensation in the perianal and genital skin and weakness of the anal sphincter muscle but does not affect rectal sensation that is most likely transmitted along the S2, S3, and S4 parasympathetic nerves. These nerve fibers traverse along the pelvic splanchnic nerves and are independent of the pudendal nerves.

EAS is made up of fast-twitch, fatigable fibers, this increased tone cannot be maintained over a prolonged period. The EAS is integral to maintaining voluntary control over the evacuation of gas and liquid stool. The pudendal nerve, which arises from the second, third, and fourth sacral nerves, innervates the EAS. A pudendal nerve block creates a loss of sensation in the perianal and genital skin and weakness of the anal sphincter muscle but does not affect rectal sensation that is most likely transmitted along the S2, S3, and S4 parasympathetic nerves. These nerve fibers traverse along the pelvic splanchnic nerves and are independent of the pudendal nerves.

TABLE 54.3 Colon and Rectal Cancer Screening Recommendations | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Anorectal Physiology

The successful storage and evacuation of fecal material relies on normal stool consistency and bowel motility, rectal compliance, an intact anal sphincter complex, and the ability to voluntarily relax the puborectalis muscle and sphincters to facilitate defecation. The physiology of voluntary bowel evacuation relies on the rectoanal inhibitory reflex (RAIR). When a bolus of fecal material is delivered to the rectum, increased rectal pressure and distension causes transient relaxation of the IAS, allowing a small sample of the rectal contents to come in contact with the sensory afferent somatic nerves innervating the anoderm. The amplitude and duration of this relaxation increases with the volume of rectal distension and is mediated by the myenteric plexus. The RAIR facilitates the discrimination of gas, liquid, or solid fecal material that is present in the rectum and permits voluntary evacuation in a socially acceptable manner. Once the conscious decision has been made to permit evacuation, the puborectalis muscle relaxes, increasing the anorectal angle and allowing passage of solid fecal material. Patients who experience paradoxical contraction of the puborectalis muscle and sphincter complex with straining suffer from severe obstructed defecation and require biofeedback and physical therapy to reverse this pathology.

Fecal Incontinence

Etiology and Pathophysiology

The etiologies of fecal incontinence are many and are listed in Table 54.4. It is helpful to divide the etiologies between those that start outside or above the pelvis versus those within the pelvis. In many cases, patients will have several abnormalities that lead to fecal incontinence, such as diarrhea-predominant IBS and a chronic third-degree laceration. The etiologies outside the pelvis include all

the pathologies that cause diarrhea or increased intestinal motility. Neurologic conditions such as multiple sclerosis, diabetic neuropathy, trauma, or neoplasms in the spinal cord or cauda equina initially begin as pathologies outside the pelvis, and the pelvic floor is presumed normal. As these neuropathies progress, the pelvic floor muscular function or rectal sensation may become impaired, resulting in fecal incontinence.

the pathologies that cause diarrhea or increased intestinal motility. Neurologic conditions such as multiple sclerosis, diabetic neuropathy, trauma, or neoplasms in the spinal cord or cauda equina initially begin as pathologies outside the pelvis, and the pelvic floor is presumed normal. As these neuropathies progress, the pelvic floor muscular function or rectal sensation may become impaired, resulting in fecal incontinence.

TABLE 54.4 Etiologies of Fecal Incontinence | |

|---|---|

|

Fecal incontinence that arises from pathology within the pelvis is largely attributed to two broad categories: direct anatomical disruption of the sphincter complex, with or without neuropathy, usually occurring with the first delivery that results in an earlier presentation of fecal incontinence and neurogenic dysfunction of the pelvic floor and sphincter complex that appears to be cumulative and leads to a presentation of fecal incontinence in later life.

Historically, incontinence secondary to pelvic floor/anal sphincter denervation has been designated as “idiopathic” and represents as many as 80% of patients with fecal incontinence. Denervation may be secondary to pregnancy, vaginal delivery, chronic straining with constipation, rectal prolapse, or descending perineal syndrome. Histologic studies of the EAS and puborectalis in women with idiopathic fecal incontinence show fibrosis, scarring, and fiber-type grouping consistent with nerve damage and reinnervation. Electromyographic studies (EMGs) have demonstrated reinnervation of the pelvic floor with increased fiber density and prolongation of nerve conduction.

Obstetric Anal Sphincter Injury

In younger women, a common cause of fecal incontinence is anatomic damage to the anal sphincter that is sustained at the time of vaginal delivery, with or without neuronal injury. Damage to the anal sphincter can occur by mechanical disruption or separation of the IAS or EAS or by damage to the muscle innervation by stretching or crushing the pudendal and pelvic nerve. In a landmark study from England in 1993, 13% of primiparous women and 23% of multiparous women developed fecal incontinence or fecal urgency at 6 weeks postpartum. All but one of the symptomatic women had evidence of anatomic anal sphincter disruption on endoanal ultrasound. While pudendal nerve studies initially showed prolongation, the vast majority demonstrated full neuronal recovery by 6 months postpartum. This study suggested that the contribution of an anatomic sphincter injury was a greater determinant of developing symptoms than denervation injury, highlighting the need to identify obstetric risk factors that are associated with anal sphincter tears.

The prevalence of clinically recognized anal sphincter lacerations varies widely and has been reported to occur in 0.6% to 20.0% of vaginal deliveries, with higher rates documented after operative vaginal delivery. Results obtained from endoanal ultrasound studies of the anal sphincter complex after one vaginal delivery demonstrate an incidence of “occult” anal sphincter disruption in 11% to 35%. Occult sphincter lacerations are not recognized at delivery, and in fact, the perineal skin may be intact with an underlying muscle tear not visible. Risk factors for both occult and clinically recognized anal sphincter disruption include midline episiotomy, operative vaginal delivery (both forceps and vacuum), persistent occiput posterior head position, prolonged second stage of labor (>2 hours), and delivery of macrosomic infants.

Persistent symptoms of anorectal dysfunction are reported by 20% to 50% of women who sustain an anal sphincter injury and have a primary repair. Overall, the prevalence of anal incontinence and fecal incontinence following visible sphincter lacerations has been reported at approximately 40% and 13%, respectively. Current evidence suggests that if a primiparous woman presents with symptoms of fecal incontinence, there is a 76.8% chance of an anal sphincter defect being identifiable on endoanal ultrasonography. Several studies that investigated women up to 5 years postpartum following a third-degree tear and a

primary repair have shown that as many as 85% will have persistent structural defects with approximately 58% subsequently running the risk of developing fecal incontinence.

primary repair have shown that as many as 85% will have persistent structural defects with approximately 58% subsequently running the risk of developing fecal incontinence.

Anal Incontinence and Symptoms Distant from Delivery

Differences in rates of incontinence reported by women with and without lacerations may fade with advancing age, depending on the time since delivery. Several retrospective studies have looked at the impact of sphincter laceration on anal incontinence symptoms and report different long-term risks. A retrospective cohort study on 125 matched pairs of women with and without a history of sphincter laceration, with a median follow-up of 14 years after index delivery, found a threefold higher risk of anal incontinence in the tear group. In contrast, a 30-year retrospective cohort study reported equal rates of anal incontinence among women who delivered vaginally with an overt sphincter rupture, in those with episiotomy without sphincter rupture, and in those who only delivered by cesarean section. Another study of 4,569 women 18 years after delivery found that only 6% of the reports of fecal incontinence were attributable to a prior sphincter tear. One prospective cohort study of 242 women 5 years after vaginal delivery identified age (OR 1.1; 95% CI 1.0 to 1.2) and prior overt sphincter laceration (OR 2.3; 95% CI 1.1 to 5.0) as well as subsequent vaginal delivery (OR 2.4; 95% CI 1.1 to 5.6) as predictive of anal incontinence symptoms.

Effect of Subsequent Vaginal Delivery

Severity of anal incontinence symptoms may be affected by subsequent vaginal delivery. A study following 117 women with a history of third- or fourth-degree lacerations 1 to 10 years after primary repair found that the 43 women who underwent another vaginal delivery had an increased risk (relative risk [RR] 1.6; 95% CI 1.1 to 2.5) of anal incontinence when compared with the risk found in the 74 women without more deliveries. The chance of developing permanent anal incontinence after a subsequent delivery may also be affected by the severity of the tear in the index pregnancy. In a series of 177 women, severe anal incontinence was reported more commonly after a second delivery in those who had sustained a fourth-degree laceration in their first delivery when compared with women who had only third-degree lacerations (P = 0.043).

The presence of transient incontinence after sphincter laceration and repair is also predictive of the likelihood of developing permanent incontinence with a subsequent delivery. In a study of 56 women with complete EAS tears, 23 (41%) had transient incontinence and 4 (7%) had permanent incontinence following their first delivery. Among the 23 with transient incontinence, 9 (39%) had recurrent symptoms with a subsequent delivery, and in 4 (17%), these symptoms became permanent. Not all studies, however, conclude that subsequent delivery negatively affects anal continence. A comparison of 125 women with third- and fourth-degree lacerations to 125 controls 14 years after their first delivery identified sphincter laceration as an independent risk factor for fecal incontinence (RR 2.54; 95% CI 1.45 to 4.45), but there was no observed increased risk with subsequent vaginal deliveries. In another retrospective analysis, 234 women who had sustained a complete third-degree laceration were contacted for phone interviews regarding continence. In this cohort, no differences were found between women with zero, one, or two subsequent deliveries, nor were there any differences between women who sustained additional third-degree laceration and those without any subsequent deliveries. These studies question whether increases in anal incontinence are due to subsequent vaginal delivery or to other influences, including age.

Anal Incontinence and Cesarean Delivery

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree