External Ear Procedures

Nestor J. Martinez

Marla J. Friedman

Introduction

The external ear is vulnerable to injury because of its exposed position. Injuries to the external ear occur in all age groups and are common among those engaged in sports activities (e.g., wrestling, cycling, martial arts) (1). Lacerations of the external ear are the most frequent form of accidental ear trauma (2). Auricular hematomas usually result from shearing injury and are often seen in boxers and wrestlers (3). Other types of external ear injury include abrasions, burns, and avulsions. Additionally, earring studs or backs may become embedded as a result of infection or excessive pressure. This usually involves the earlobe but can occur in other parts of the ear where a piercing has been done (4). The goal of treatment of these conditions is to restore the normal appearance of the ear while preventing complications such as infection or abnormal cartilage formation.

Anatomy and Physiology

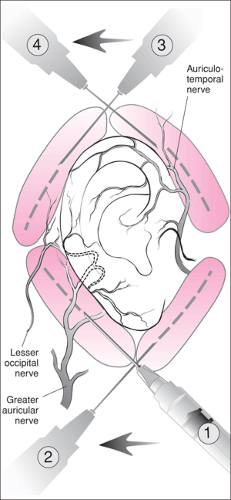

The external ear consists of the auricle and the external auditory canal. The auricle is composed of cartilage covered by tightly attached perichondrium and skin on the external surface. The lobule is without cartilage and is composed of soft tissue and skin only. Anteriorly, the skin of the helix and antihelix region is firmly adherent to the cartilage. The perichondrium and skin behind the auricle are separated from the cartilage by a thin layer of subcutaneous tissue and are more loosely attached. The vascular supply to the skin and perichondrium is provided by the superficial temporal artery and the posterior and deep auricular branches of the external carotid artery. Four nerve branches provide sensory innervation to the outer ear. The outer portion of the auricle receives its innervation from the greater and lesser auricular nerves, while the more medial portion receives innervation from the auriculotemporal nerve (Fig. 55.1). The auricular branch of the vagus nerve innervates the external auditory meatus and much of the concha (5,6).

The cartilaginous tissue of the auricle lacks its own blood supply. Instead, the cartilage of the ear is nourished by the surrounding perichondrium. Blunt trauma can disrupt the normal relationship between these two structures. If the cartilage becomes denuded or separated from the perichondrium by an auricular hematoma, ischemia may occur without proper treatment, potentially resulting in infection or necrosis of the cartilage. As the cartilage dies, it is replaced by fibrocartilaginous scar tissue, resulting in the cosmetic deformity known as “cauliflower ear” (7). Hematoma or seroma can occur after closure of a laceration to the external ear, but this is less likely when a proper dressing is applied.

Indications

More than half of all ear lacerations occur in the pinna, and the extent of injury is usually immediately obvious (2). However, in some cases blood from ear or other facial lacerations may conceal exposed perichondrium, cartilage, or additional lacerations, especially behind the ear. Small, simple lacerations of the ear should undergo primary skin closure. It is important not to leave any exposed cartilage after closure, as this increases the risk of infection and chondritis. If the cartilage is minimally injured, closing the skin over the cartilage should result in an adequate repair. However, if the cartilage requires suturing to maintain its stability, or if there is exposed cartilage that may require skin grafting, a surgical consultation should be obtained. Consultation is also advisable in cases of complex cartilage injury that may require débridement. When the laceration involves the external ear canal, surgical consultation is recommended, because stenosis of the canal is possible without the appropriate management and follow-up (3,8).

Auricular hematomas require prompt, meticulous drainage in order to prevent ensuing complications. Drainage must be complete, and the appropriate dressing should be applied. Timely follow-up within 24 hours is of paramount importance in the management of these injuries, since blood frequently accumulates again after the initial drainage (3,9).

A mastoid dressing or a customized pressure dressing should be applied to the ear following the repair of most complicated ear lacerations and following drainage of auricular hematomas. This dressing serves to prevent further bleeding and hematoma or seroma formation (8). It also helps to maintain the normal contour of the external ear.

Embedded earring backs must be removed to prevent foreign body impaction, scarring, disfigurement, and infection. Removal of an earring back is a simple procedure once adequate anesthesia is performed. Proper wound care following extraction should be provided.

Equipment

Auricular Block

Antiseptic solution

Syringe, 10 mL

Needle, 25 to 27 gauge, 1½ inch

Lidocaine 1% without epinephrine, 10 to 15 mL

External Ear Laceration Repair

Antiseptic solution

Syringe, 20 mL, with protective shield for irrigation

Sterile water or saline for irrigation

Syringe, 10 mL

Needle, 25 to 27 gauge, 1½ inch

Lidocaine 1% without epinephrine

Skin sutures, 6.0 nonabsorbable monofilament

Cartilage sutures, 6.0 absorbable Vicryl

Auricular Hematoma Aspiration

Antiseptic solution

Lidocaine 1% without epinephrine, if needed

Syringe, 10 mL

Needle, 18 gauge

Scalpel with No. 15 blade

Curved hemostat

Mastoid or Pressure Dressing

Cotton balls soaked in saline or mineral oil or petroleum gauze

Gauze pads (4) 4″ × 4″ with partial cut in center

Gauze pads (4) 4″ × 4″ without center cut

Gauze wrap-around bandage, 4 inch

Removal of Embedded Earring Backs

Antiseptic solution

Syringe, 1 mL

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree