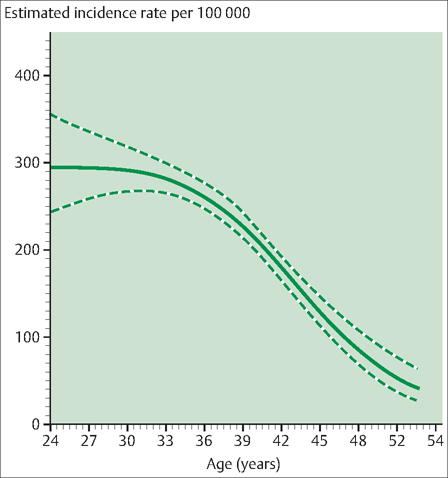

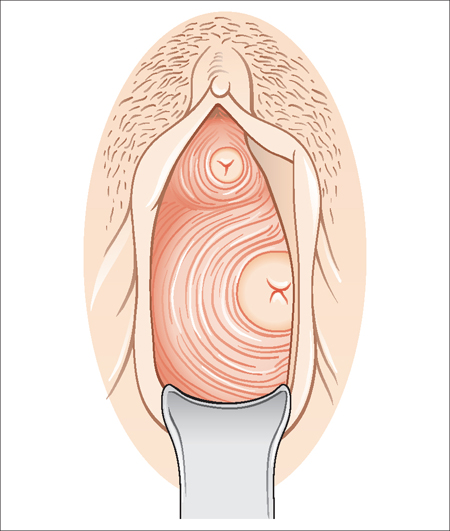

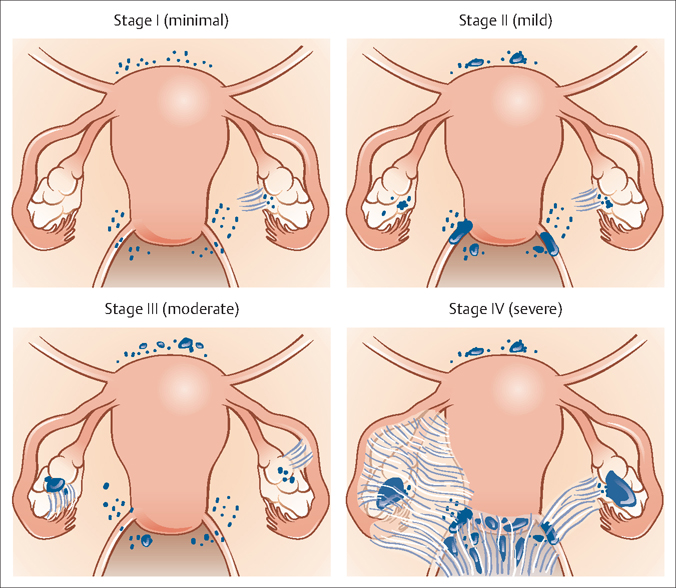

33 Endometriosis and Adenomyosis Robert L. Barbieri Endometriosis is the presence of endometrial glands and/ or stroma outside of the uterus. Women with endometriosis typically present for medical care with one or more of the following three problems: Approximately 5% of women between the ages of 15 and 45 years have endometriosis. The peak incidence appears to occur between 20 and 30 years of age (Fig. 33.1). In sharp contrast, the peak incidence of uterine leiomyomas (fibroids) occurs between 35 and 45 years of age. Many reproductive exposures influence the risk of developing endometriosis. Reproductive factors that increase the risk of developing endometriosis include early menarche, short menstrual cycles of less than 26 days, prolonged menstrual flow lasting more than 7 days, nulliparity, and low circulating androgen levels. Reproductive factors that decrease the risk of developing endometriosis include multiple births, long intervals of lactation, oligo- or amenorrhea, and late menarche. Many mechanisms may contribute to the development of endometriosis including: Fig. 33.1 Age-specific incidence of laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis among premenopausal women with no past infertility history in the Nurses’ Health Study II (1989–1999) Dashed and dotted lines, 95% confidence intervals. Historically, retrograde menstruation has been the most commonly cited theory for the development of endometriosis. In humans and nonhuman primates, cervical stenosis—an anatomical abnormality that results in an increase in the volume of retrograde menstruated endometrium—uniformly results in the development of endometriosis if estrogen is present. Hormonal factors play a key role in the development of endometriosis. Estrogen stimulates the growth of endometriosis. Physiological levels of progesterone also support the growth of endometriosis. Androgens decrease the growth of endometrial glands and stroma. Women with high levels of estrogen and low levels of androgen are at increased risk for developing endometriosis. Women with low levels of estrogen (amenorrhea, menopause) and high levels of androgens (polcystic ovary syndrome) are at low risk of developing endometriosis. Pharmacologic doses of androgenic progestins (norgestrel) decrease the growth of endometriosis tissue. Endometriosis requires estrogen for its continued growth. Bilateral oophorectomy is uniformly effective in the treatment of endometriosis. The most common symptoms reported by women with endometriosis are dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and pain with bowel movements (dyschezia). Based on the history, it is often difficult to distinguish the dysmenorrhea associated with endometriosis from that caused by primary dysmenorrhea (dysmenorrhea caused by prostaglandin stimulation of the uterine muscle). However, women with endometriosis and dysmenorrhea often report that the pelvic pain is not well relieved by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents. Most women with endometriosis are nulliparous. Unlike women with primary dysmenorrhea, many women with dysmenorrhea and endometriosis present with severe pain to emergency rooms or have frequent doctor visits for pelvic pain. Women with pelvic pain that is impacting their daily life function and is not relieved by ibuprofen or cyclic oral contraceptives should be counseled regarding the option of laparoscopic surgery to diagnose endometriosis. About 40% of women with endometriosis and pelvic pain have a significant physical finding on pelvic examination. The most common physical findings associated with endometriosis are: Women with advanced endometriosis often have ovarian cysts and these may be palpable on bimanual examination. Extensive training in pelvic examination techniques, such as a residency in gynecology, is necessary to reliably recognize uterosacral ligament thickening or nodularity. However, lateral cervical displacement and cervical stenosis can be diagnosed with less extensive training. Lateral cervical displacement is present when the outer border of the cervix is lateral to the axial mid-line. For the majority of women, the cervix is reliably within the axial midline. For about 25% of women with endometriosis, the outer border of the cervix is lateral to the axial midline. Cervical stenosis is likely present if the diameter of the cervical os is less than 4 mm. The common cotton-tipped applicator used in medicine has a maximal diameter of approximately 4.5 mm. If the cotton-tipped applicator cannot ft into the cervical os, the clinician should be alert that cervical stenosis may be present. About 5% of women with endometriosis have cervical stenosis. Fig. 33.2 In normal women, the body of the cervix is inside the axial midline In some women with endometriosis, shortening of one uterosacral ligament because of scarring has pulled the cervix to the ipsilateral side of the vagina, resulting in lateral displacement of the cervix In lateral displacement of the cervix, the body of the cervix is lateral to the axial midline. The “gold standard” for the diagnosis of endometriosis is surgical visual diagnosis, typically performed by laparoscopy. Laparoscopy is an ambulatory surgery procedure that is typically performed under general anesthesia. An advantage of surgical diagnosis of endometriosis is that therapeutic excision or ablation of the endometriosis implants can occur at the same time as the diagnostic surgery. At the time of laparoscopy, a systematic and comprehensive assessment of the pelvis and lower abdomen permits the detection of even very small implants (1 mm in diameter) of endometriosis. The most common locations of endometriosis are: Endometriosis may also occur outside the pelvis on the pleural lining causing catamenial hemothorax. Alternative approaches to the diagnosis of endometriosis have been proposed, but are not uniformly accepted. For example, some authorities have recommended that in a woman with a classic history and physical exam findings of endometriosis—such as progressive, severe dysmenorrhea and physical exam findings of uterosacral ligament nodularity—a presumptive clinical diagnosis of endometriosis can be made and treated with hormones. No nonsurgical imaging methodology is effective in diagnosing endometriosis. Investigators have tried to identify serum markers for the presence of endometriosis. The best available serum marker of advanced endometriosis is CA-125. Approximately 70% of women with moderate and severe endometriosis have elevated serum levels of CA-125. However, the majority of women with minimal and mild endometriosis have normal levels of CA-125. Also, gynecologic diseases such as fibroids and pelvic inflammatory disease can sometimes cause elevations of CA-125, reducing the specificity of this test for the diagnosis of endometriosis. The differential diagnosis of endometriosis includes adenomyosis, pelvic inflammatory disease, chronic appendicitis, uterine leiomyomas, diverticulitis, and ovarian neoplasms. At the time of laparoscopy, the extent of the endometriosis lesions should be assessed to surgically stage the disease. The American Society of Reproductive Medicine recognizes four stages to the disease process. Minimal disease (stage I) involves a few small peritoneal lesions of endometriosis. Mild disease (stage II) involves the presence of many small peritoneal lesions of endometriosis. Moderate disease (stage III) typically involves the presence of peritoneal lesions of endometriosis, plus ovarian cysts containing endometriosis tissue (endometriomas) and minor pelvic adhesions. Severe disease (stage IV) typically involves ovarian cysts of endometriosis and major pelvic adhesions and scarring (Fig. 33.3). For the purposes of planning treatment, stages I and II can be combined as “early-stage endometriosis” and stages III and IV can be combined as “advanced endometriosis.” In a review of 100 consecutive cases of endometriosis, the distribution of stages was: stage I 41%, stage II 32%, stage III 15%, and stage IV 12%. Most women with endometriosis typically present with one or more of the following three complaints: Treatment is focused on the specific complaint of the patient. Endometriomas are ovarian cysts containing endometriosis tissue. Evidence suggests that endometriomas are monoclonal tumors that arise from a somatic mutation in a precursor cell. In general, endometriomas do not regress spontaneously. Hormone treatment may cause the endometrioma to shrink in size, but they return to their pretreatment size after hormone treatment is discontinued. Endometriomas are complex ovarian cysts because ultrasound typically demonstrates the presence of complex echoes within the cyst. Generally, persistent, complex ovarian cysts need to be surgically removed to achieve a definitive diagnosis. Some complex ovarian cysts are caused by ovarian cancer. Surgical removal and pathological analysis are required to determine the cause of a complex ovarian cyst. Some clinicians will expectantly manage small, nongrowing complex cysts (<4 cm in diameter) that are thought to be en-dometriomas. This approach may spare the patient a surgical procedure where some normal ovarian tissue will be removed and scar tissue might arise postoperatively. Fig. 33.3 Visual examples of the four stages of endometriosis Seventy-five percent of cases of infertility are caused by: About 25% of cases of infertility are not associated with these three problems. Among these 25% of cases, approximately 40% of the female partners (8% of all infertility couples) have endometriosis. Many authorities recommend that female partners of infertile couples should have a laparoscopy to look for endometriosis if the initial infertility evaluation (detection of ovulation, semen analysis, hysterosalpingogram) is normal. At the time of initial diagnostic laparoscopy, the endometriosis lesions can be excised. For infertile couples with infertility due to endometriosis, a stepwise approach to treatment is warranted (Table 33.1). One large, well-designed randomized study has reported that surgical treatment of endometriosis is effective in improving fertility in couples where the woman has minimal or mild endometriosis (see Evidence Box 33.1). Treatment of women with pelvic pain caused by endometriosis typically involves a stepwise approach that begins with inexpensive treatments with few side effects and progresses to expensive treatments with many side effects. Hormonal treatment of endometriosis is based on the following facts: Surgical treatment of endometriosis is based on two concepts:

Endometriosis

Definition

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Etiology

History

Physical Examination

Diagnosis

Staging

Treatment

Endometriomas

Infertility

Pelvic Pain That Impacts function

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree