PREVALENCE

The estimated prevalence of endometriosis among population groups varies depending on the presenting symptoms. Endometriosis affects 6% to 10% of reproductive-age women. Among women with pelvic pain, the prevalence of endometriosis ranges from approximately 30% to 80%. The disease has been diagnosed in 40% to 52% of women with severe dysmenorrhea and 70% of patients with chronic pelvic pain. Cramer and colleagues, in a multicenter study, diagnosed endometriosis in 17% of women with primary infertility, and in other series, the prevalence varied from approximately 9% to 50%. Verkauf prospectively identified endometriosis in 38.5% of infertile women and 5.2% of fertile women. Other studies have confirmed the odds that infertile women are seven to 10 times more likely to have endometriosis than are their fertile counterparts. However, any postmenarchal woman is at risk, because endometriotic implants have been identified in postmenopausal women, in women with primary amenorrhea secondary to müllerian anomalies, and in 69.6% of teenagers who underwent diagnostic laparoscopy for chronic pelvic pain. Twin and family studies suggest a genetic component. Simpson and colleagues reported a 6.9% occurrence rate in first-degree female relatives, which compared with 1% for the non-blood-related control group. Genes involved in implantation of tissue, fibrinolysis, or ovarian steroidogenesis may be aberrantly expressed at a higher frequency in family members with endometriosis. Other risk factors include alcohol use, smoking, and low body mass index.

HISTOGENESIS

The mechanism by which endometriosis develops is unknown, although there has been much discussion as to its origin (

Table 22.1). Variations in the location and presentation of implants have compromised a complete understanding of the histogenesis of the aberrant endometrial cells. Four major theories have been proposed:

The reflux and direct implantation theory suggests that viable endometrial cells reflux through the fallopian tubes during menstruation and implant on surrounding pelvic structures.

The coelomic metaplasia theory suggests that the multipotential cells of the coelomic epithelium may be stimulated to transform into endometrial-like cells.

The vascular dissemination theory suggests that endometrial cells enter the uterine vasculature or lymphatic system at menstruation and are transported to distant sites.

The autoimmune disease theory suggests that endometriosis is a disorder of immune surveillance that allows ectopic endometrial implants to grow.

Reflux and Direct Implantation Theory

John Sampson first postulated that endometriosis arose from retrograde flow of fragments of endometrial tissue through the oviducts and into the peritoneal cavity. Much evidence validates this theory. The anatomic distribution of endometriosis as noted at laparoscopy is consistent with a reflux pattern of development; the most common sites of disease in the infertile woman are the ovary and uterosacral ligament, followed by the posterior uterus, posterior cul-de-sac, and posterior broad ligament. Endometriosis developed in monkeys when the uterus was surgically inverted to cause menstruation to occur intraperitoneally. Exposure of abraded peritoneum to endometrial cells has resulted in the growth of endometriotic implants in rabbits and rats. Endometriosis has developed in laparotomy, episiotomy, and cesarean section scars after surgical entrance into the endometrial cavity, and anomalies of the müllerian tract are associated with an increased occurrence of endometriosis. Endometriosis is a common finding in women with stenosis of the external cervical os. Epidemiologic data suggest that women who menstruate more frequently, more heavily, or for a longer duration have an increased likelihood of disease development. Prolonged lactation and multiparity are protective.

Peritoneal implants of endometriosis and the presence of endometriomas are more common on the left side of the pelvis than the right. The position of the sigmoid colon creates a sequestered microenvironment around the left adnexa, which facilitates implantation of endometrial cells regurgitated through the left tube. The large intestine does not provide the right hemipelvis with this anatomical shelter, because the cecum lies more cranial in position. In addition, the retrograde menstruation theory is supported by the finding of a higher prevalence of endometriosis in the subphrenic region, since the falciform ligament may trap refluxed endometrium in the right hypochondrium.

Focal endometriosis has been identified in 16% to 63% of proximal tubal segments after cautery or Pomeroy tubal sterilization, perhaps as a consequence of recurrent bathing of the healing terminal area with menstrual products. Nevertheless, bloody peritoneal fluid has been observed in 90% of women with patent fallopian tubes undergoing laparoscopy during the perimenstrual time period, a figure much greater than the estimated 2% to 5% prevalence of symptomatic endometriosis in women of reproductive age. Additionally, peritoneal implants have been identified in women who had a prior tubal ligation procedure and were undergoing laparoscopy for the evaluation of pelvic pain. Hence, other factors evidently are present to promote the ectopic implantation.

Coelomic Metaplasia Theory

The germinal epithelia of the ovary, endometrium, and peritoneum all originate from the same totipotential coelomic epithelium. The metaplasia theory postulates that these totipotential cells are transformed by repeated exposure to hormonal or infectious stimuli. This may explain the development of endometriotic lesions in unusual locations and in the odd cases of male patients in whom endometriosis develops after prostatectomy, orchiectomy, or prolonged treatment with estrogen. Reports of endometriosis in women with primary amenorrhea and an absence of functioning uterine endometrium and of endometriosis identified in mature teratomas also lend support to the metaplasia theory.

Vascular Dissemination Theory

Endometrial cells can be transported to extrauterine sites by blood vessels or the lymphatic system or by contamination of the pelvis or abdominal wall incision if the uterine cavity is surgically entered. Retroperitoneal endometriosis is hypothesized to arise from lymph vascular spread; 29% of patients with pelvic endometriosis documented on autopsy had pelvic lymph nodes that contained endometriosis. Theories of vascular dissemination help explain how endometriosis can develop in the lung or pericardium.

Autoimmune Disease Theory

Alterations in cellular immunity can facilitate the successful implantation of translocated endometrial cells. Compared with control subjects, monkeys with spontaneous endometriosis had both a lowered cell-mediated response to autologous endometrial tissue, as determined by skin testing, and a decreased in vitro blastogenesis response. Similar studies performed in women demonstrated that lymphocytes obtained from control patients were significantly more efficient in cytolysis of isolated endometrial stromal cells than were lymphocytes obtained from patients with endometriosis. This decreased cytotoxic response to endometrial cells may be due to a defect in natural killer cell activity, such as a decreased lytic effect toward stroma that allows ectopic development of endometrial fragments. In addition, there may be an increased resistance of endometrium in women with endometriosis to natural killer cytotoxicity.

Promoting Factors

Clinical and laboratory studies support the concept that endometriosis is an estrogen-dependent condition. Estradiol concentrations greater than approximately 60 pg/mL have been identified as necessary for proliferation of endometriotic lesions. Nevertheless, estrogen and progesterone receptors are found in much lower concentrations in endometriotic tissue than in normal endometrium tissue; such endometriotic tissue also frequently fails to show cyclic variations of development in response to hormonal changes. Early data from primate studies suggested that endometriosis required no steroidal supplementation to become initially established, but later studies demonstrated that chronic exposure to ovarian steroids is necessary for the survival of these experimentally induced endometrial plaques.

Growth factors can originate from the peritoneal environment to stimulate endometrial development. Platelet-derived growth factor, a macrophage secretory product, enhance endometrial stromal cell proliferation in a dose-dependent manner. Similarly, macrophage-conditioned media promote mouse endometrial stromal cell proliferation in vitro, and this activation is enhanced with the addition of estrogen. Increased concentrations of macrophage-derived growth factors, including vascular endothelial growth factor, have been identified in the peritoneal fluid of women with endometriosis. This suggests that changes in the vascular permeability and angiogenesis play an important role in the pathophysiology of this disease.

Molecular alterations in steroidogenic enzyme function have been implicated in the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Endometrial tissue from patients with endometriosis expresses aromatase P-450, whereas endometrium from control women without identifiable endometriosis does not. The presence of aromatase within endometriosis results in higher local production of estrogen necessary to support the growth and metabolic activity of the lesion.

Menstrual effluent contains factors that induce alterations in the peritoneal mesothelium, facilitating adhesion of endometrial cells. Attachment of endometrial cells is enhanced by induction of adhesion molecules and their receptors and the overexpression of matrix metalloproteinases and plasminogen activators. These factors ensure local destruction of the extracellular matrix. Suppression of matrix metalloproteinase production by progesterone decreased ectopic implantation of endometrium in the nude mouse, implicating these proteinases in the pathogenesis of endometriosis.

In summary, no single theory explains all cases of endometriosis, although the direct implantation mechanism seems the likely cause for most disease locations. Immunologic factors, inducing substances, or other mediators may explain the development of endometriosis in more distant sites.

NATURAL HISTORY

The natural history of endometriosis is not clearly understood. The disease appears to progress in most untreated patients, although spontaneous regression can occur in as many as 58% of milder cases. Falcone and Lebovic analyzed the findings of follow-up laparoscopies performed 6 to 39 months following the initial diagnostic procedure among 162 patients in several previous endometriosis surgical trials that were randomized to the placebo control group rather than surgical excision/ablation. There was nearly equal distribution of those with progressive disease (31%), unchanged (31%), and improvement in extent of lesions (38%).

Surgical and medical therapies may promote a temporal regression but may not effectively eliminate microscopic, retroperitoneal, and hormonally resistant disease. Dmowski and Cohen described persistent disease in 15% of patients treated with danazol, and Henzl and associates noted a progression of disease during the course of treatment in 4% to 8% of patients receiving danazol or an analogue of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH). When conservative surgery was combined with danazol or GnRH agonist therapy, the overall recurrence rate at 36 months was between 13.5% and 33%.

The effect of pregnancy on the clinical course of endometriosis is uncertain. Although Sampson proposed that pregnancy induces involution of implants, other authors recently described a variable response of endometriosis to pregnancy. McArthur and Ulfelder analyzed the clinical effect of pregnancy on endometriosis in 24 patients. They found that the behavior of endometriosis during the gravid state was extremely variable and that the regression of disease appeared to be due to decreased tissue responsiveness to hormonal stimulation rather than to actual necrosis of the lesions. More patients in their series experienced disease persistence than permanent regression. Monkey studies have confirmed these findings; the response of endometrial implants to pregnancy varied from total regression to significant progression.

Approximately 2% to 4% of early postmenopausal women suffer from endometriosis. These cases are usually associated with exogenous intake of estrogens or tamoxifen. Nevertheless, there are reports of symptomatic endometriosis in women older than 60 years of age who have not received steroid replacement therapy. Such cases presumably are secondary to the responsiveness of the residual lesions to low levels of estrogens that arise from peripheral conversion of ovarian and adrenal androgens.

CLASSIFICATIONS

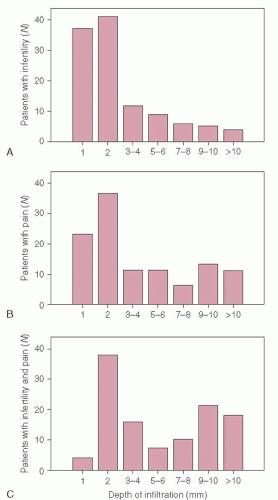

Many endometriosis classification systems have been introduced to allow direct comparison of patient responses to medical and surgical treatments and to identify factors predictive of disease outcome. No system has yet been devised that is entirely satisfactory. The AFS (renamed the American Society for Reproductive Medicine) organized a panel of experts in 1979 to develop a classification system that might serve as a basis for evaluating various therapies. The committee devised an innovative scheme based on the natural progression of the disease. Three anatomic areas—the peritoneum, ovary, and fallopian tube—were examined for the presence of endometriosis or adhesions, with allowances made for unilateral involvement. However, the system was not weighted for depth of infiltration of peritoneal implants. A point system instead assigned values to each area of disease involvement based on the presumption that implant area and adhesion characteristics were most often associated with disease prognosis. The stage of disease was determined by the cumulative score of the assigned points. This classification system was criticized for its arbitrary division of endometriosis into categories that did not necessarily reflect the true relative risk of disease sequelae, pain, and infertility.

The AFS classification was revised in 1985 to provide a more standard assessment of endometriosis for correlation of surgical treatment with distribution and severity of implants (

Table 22.7). The point range of mild disease was expanded, and greater weight was given to deep endometriosis, dense adhesions, and cul-de-sac obliteration by adhesive disease. Although the revised staging system appropriately acknowledges the importance of adhesive disease and endometriomas, most women with extensive peritoneal disease in the absence of ovarian involvement, particularly deeply invasive implants, receive a very low score on laparoscopic inspection of the lesions.

This revised AFS classification has been widely used by investigators to categorize disease states. Nevertheless, direct comparison of treatment outcome is compromised by inconsistencies in the application of the staging criteria and by the great variations in medical and surgical therapeutic options being applied in the management of endometriosis. Evaluation of the extent of disease by laparoscopy may be limited by a lack of recognition of atypical implants, particularly if the patient is hypoestrogenic as a result of recent discontinuation of medical therapy for endometriosis. Furthermore, the divisions between stages of endometriosis remained arbitrary, the

point score for ovarian involvement was weighted too heavily, and the classification scheme did not address disease involving the fallopian tubes, intestines, or urinary tract. Also, there were no parameters to indicate the present activity and state of evolution of the disease.