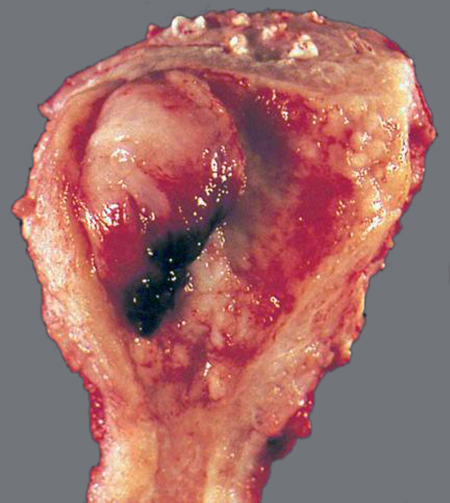

50 Endometrial Cancer Robert L. Barbieri Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic malignancy (Fig. 50.1). After breast, lung, and colon cancer, it is the fourth most common cancer in women living in developed countries. Of all cancers in women, about 6% are due to endometrial cancer. Endometrial cancer is a pathological diagnosis, which is made when histological study indicates disruption of the normal endometrial epithelial cell and glandular growth and architecture with invasion of neoplastic epithelium into the underlying stroma. The abnormal pattern of growth and architecture is most often caused by somatic mutations that reduce the normal mechanisms which constrain uncontrolled cell growth. A precursor to endometrial cancer is endometrial hyperplasia. Simple endometrial hyperplasia has a low rate of progression to endometrial cancer. Complex endometrial hyperplasia, including cellular atypia, has a higher rate of progression to endometrial cancer. Endometrial cancer is often characterized as type I (primarily induced by hormone imbalance: too much estrogen and too little progesterone) and type II (not primarily related to hormone imbalance). Type I endometrial cancer typically presents histologically as a low-grade tumor with endometrioid features. Type I endometrial cancer is primarily induced by extended endometrial stimulation by estrogen without exposure to progesterone. Common clinical conditions where there is chronic exposure to estrogen without exposure to progesterone include: 1) anovulatory states such as the polycystic ovary syndrome; 2) exogenous estrogen therapy without progestin treatment; 3) obesity; and 4) estrogen-secreting granulosa cell tumors. Obesity and insulin resistance can cause anovulation resulting in the common triad of endometrial cancer, diabetes, and hypertension. Type II endometrial cancer is unrelated to estrogen stimulation and commonly presents histologically as a high-grade tumor with papillary serous or clear cell features. Women with type II endometrial cancer tend to be older with a history of more pregnancies than those with type I disease. Of all cases of endometrial cancer about 75% are type I and 25% are type II. Fig. 50.1 Endometrial cancer in a hysterectomy specimen The uterus has been cut open to assess the extent of the cancer From: Silverberg, SG, Kurman, RJ Tumors of the Uterine Corpus and Gestational Trophoblastic Disease AFIP Atlas of Tumor Pathology, version 2 0, American Registry of Pathology, Washington DC 1995. Type I endometrioid endometrial cancers have characteristic mutations in the PTEN, k-ras and beta-catenin genes and demonstrate DNA microsatellite instability. The PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homologue) gene is a suppressor of estrogen-stimulated endometrial cell growth. Mutations in the PTEN gene that result in loss of function cause greater endometrial cell growth in response to a given concentration (dose) of estradiol. Type II serous endometrial cancers often have mutations in p53, which is a tumor suppressor gene that blocks the progression of cells through the late G1 phase. Loss of function mutations in p53 releases somatic cells from the G1 cell cycle checkpoint and permits the cells to replicate more rapidly. In addition, normally expressed wild-type p53 prevents cells with DNA damage from proliferating. Loss of function mutations in p53 is associated with chromosome instability increasing the likelihood that additional detrimental mutations will accrue. In the Lynch syndrome (also called the hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer syndrome), autosomal dominant germ-line mutations in the DNA mismatch repair genes, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, or PMS2, cause a multi organ cancer syndrome associated with colon, ovary, and endometrial cancer. Among women less than 50 years of age with endometrial cancer, about 10% have the germline mutations characteristic of the Lynch syndrome. The median age of diagnosis is 61 years with most women diagnosed between 50 and 70 years of age. A number of exposures reduce the risk of developing endometrial cancer, including multiparity, estrogen—progestin contraceptive use, chronic progestin therapy, and cigarette smoking. Exposures that increase the risk of developing endometrial cancer include advancing age, obesity, chronic estrogen treatment without concomitant progestin treatment, tamoxifen therapy, and nulliparity. Exposure to estrogen, unopposed by progestin, is a major risk factor for endometrial cancer. In obese women, fat cells containing aromatase produce excess extra-ovarian estrogen. In addition, obesity is often associated with anovulation, reducing progesterone secretion. Any intervention that reduces the prevalence of obesity will likely reduce the risk of endometrial cancer. Increasing exercise and reducing glycemic load are two interventions that likely reduce the risk of endometrial cancer. Unlike tamoxifen, which acts as an estrogen agonist in the endometrium and increases the risk of endometrial cancer, a related compound, raloxifene, is an anti-estrogen in the endometrium. Raloxifene use reduces the risk of endometrial cancer by about 50% in postmenopausal women. Abnormal patterns of uterine bleeding, especially in postmenopausal women, may be caused by endometrial lesions such as endometrial hyperplasia, endometrial cancer, polyps, or submucus fibroids. Women with a uterus who take estrogen, but no progestin, are at high risk of developing endometrial hyperplasia and cancer. Tamoxifen, a mixed estrogen agonist—antagonist, which acts as an estrogen agonist in the endometrium, is associated with an increased risk of endometrial cancer. A history of diabetes, hypertension, and/or obesity should increase the clinical suspicion that endometrial cancer may be present. Obesity and hypertension are common physical findings in women with endometrial cancer. Acanthosis nigricans, a dermatological finding observed in women with insulin resistance, may be present in some women with endometrial hyperplasia or cancer. Most cases of endometrial cancer are stage I. Other than bleeding from the uterus, there may be no additional abnormal findings on physical examination. All postmenopausal women with abnormal bleeding should have an endometrial biopsy, which has more than 95% sensitivity for detecting endometrial cancer. To fully evaluate the uterine cavity and endometrium, a hysteroscopy is often combined with an endometrial biopsy, especially if a recent endometrial biopsy did not reveal the cause of the bleeding. In postmenopausal women with uterine bleeding who completed a thorough evaluation, the causes of the bleeding are listed in Table 50.1

Definition

Etiology

Epidemiology

Prevention

History

Physical Examination

Diagnosis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree