Emergency Management of Selected Congenital Anomalies

Gail S. Rudnitsky

Sonia O. Imaizumi

Introduction

Congenital anomalies requiring surgical intervention in the immediate postnatal period are not uncommon. Approximately 2% of all newborns will have a serious surgical or cosmetic anomaly (1). With improvements in monitoring capabilities and increased use of high-resolution ultrasonography, most babies with congenital anomalies are diagnosed in utero and delivered in a tertiary care center with the appropriate specialists standing by to care for these high-risk infants. However, unforeseen circumstances, such as lack of prenatal care or unexpected premature deliveries, may result in an infant being born in an emergency center or delivery room of a hospital not equipped to care for an infant with such an anomaly. Therefore, it is necessary for the treating physician to be able to stabilize an infant before transport to a hospital that is capable of caring for an infant born with a congenital malformation. Stabilization should include standard neonatal resuscitative measures (Chapter 36), including stabilizing the airway and cardiovascular system when necessary, keeping the infant warm, and preventing any exposed organs from injury or drying out. The accepting hospital should be a tertiary care center with the appropriate surgeons and subspecialists available to provide definitive care for these children. Discussion in this chapter will be limited to several of the more common and severe malformations that require immediate attention.

Abdominal Wall Defects

Anatomy and Physiology

The more common abdominal wall defects include gastroschisis, omphalocele, bladder exstrophy, and cloacal exstrophy. All these defects require immediate intervention to prevent loss of heat and fluids and to minimize the chance of fatal infections.

Gastroschisis

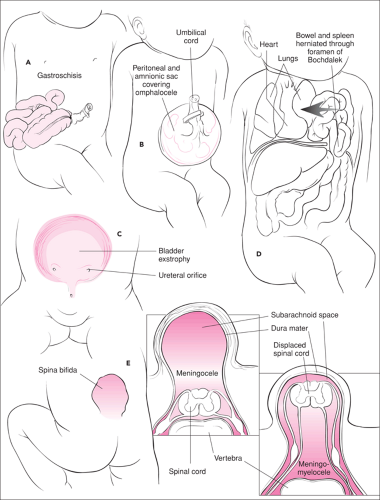

Gastroschisis is a full-thickness defect of the abdominal wall, varying from a few centimeters in length to a large defect that extends from the xiphoid process to the pubic symphysis and with herniation of uncovered intestinal contents through the defect (2) (Fig. 39.). The origin of this disorder is still unknown, but gastroschisis may arise from incomplete closure of the lateral folds during the fourth week of gestation or from rupture of the lateral umbilical ring (3). This anomaly can be differentiated from an omphalocele by the generally smaller size of the defect, which is located lateral to the umbilicus. In gastroschisis, the umbilical cord is normally attached to the abdominal wall to the left of the defect (1). Because no amniotic or peritoneal sac covers the bowel, it is exposed to the chemical irritation of amniotic fluid in utero and is often edematous, matted together, and covered with a gelatinous exudate (4). All infants have nonrotation and abnormal fixation of the intestines. Of infants with gastroschisis, 16% will have gastrointestinal malformations consisting of atresias and stenoses. Other associated congenital anomalies are rare (5). The incidence of gastroschisis is approximately 1 per 10,000 live births (6).

Omphalocele

Omphalocele, by contrast, is a 2- to 15-cm defect of the umbilical ring resulting from failure of fusion of the four somatic folds that define the abdominal wall early in gestation (1), with herniation of varying amounts of abdominal viscera into a sac composed of amnion and peritoneum (Fig. 39.1B). This sac may be ruptured before or at the time of delivery,

exposing the viscera to amniotic fluid or the ambient environment. The size of the defect and covering sac determines the amount of viscera that is herniated. Omphalocele may be associated with other abnormalities (cardiac, neurologic, genitourinary, skeletal, and chromosomal) as well as the following syndromes: Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome; prune belly syndrome; trisomies 13, 18, and 21; and pentalogy of Cantrell (2).

exposing the viscera to amniotic fluid or the ambient environment. The size of the defect and covering sac determines the amount of viscera that is herniated. Omphalocele may be associated with other abnormalities (cardiac, neurologic, genitourinary, skeletal, and chromosomal) as well as the following syndromes: Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome; prune belly syndrome; trisomies 13, 18, and 21; and pentalogy of Cantrell (2).

Figure 39.1 Selected congenital anomalies. A. Gastroschisis. B. Omphalocele. C. Exstrophy of the bladder. D. Diaphragmatic hernia. E. Spina bifida. |

Indications

These defects in the abdominal wall should be readily apparent on observation. Management of gastroschisis and omphalocele from delivery to transport is nearly identical and should be initiated once either diagnosis is suspected.

Equipment

Sterile gloves

Radiant warmer

Routine neonatal resuscitation equipment (Chapter 36)

Sterile gauze

Sterile saline

Sterile intestinal bag

Plastic film wrap (e.g., Saran or Glad)

Nasogastric tube (8 to 10 French)

Procedure

In addition to the routine neonatal resuscitative measures outlined in Chapter 36, the goals of stabilizing these infants are to minimize heat and fluid loss and to prevent desiccation, injury, or infection of the exposed viscera. Care must be taken in placing the umbilical cord clamp so as to avoid injury to the herniated intestine.

The infant is placed under a radiant warmer, and the exposed viscera are protected with a warm, sterile, saline-soaked dressing. The exposed viscera should be inspected to ensure that it is not twisted or kinked, which can result in vascular or caval obstruction. A change in color of the exposed bowel from pink to gray may indicate the presence of such an obstruction. Tension on the mesentery may be reduced by supporting the bowel on packs of warm, sterile, wet gauze (2). As soon as possible, the infant should be placed in a sterile intestinal bag with the drawstring tied around the chest (Fig. 39.2A). If the infant is small, the arms also can be enclosed (1). This clear plastic bag has the following advantages: heat and fluid loss are minimized, and it allows the physician to observe the color of the bowel, looking for signs of ischemia. An 8 to 10 French nasogastric tube should be placed to free drainage and should be aspirated every 10 to 15 minutes to prevent vomiting and to keep the bowel decompressed. Fluid resuscitation should be initiated with 10 to 20 mL/kg of colloid, Ringer lactate, or normal saline solution. Maintenance fluids of D10 ¼ normal saline should be started at twice the calculated normal maintenance volume and continued until the urine output is 2 to 3 mL/kg/hour (4). Broad-spectrum antibiotics (ampicillin and gentamicin) should be started after a baseline blood culture is obtained. Transport should be promptly arranged to a tertiary care center with an available neonatologist and pediatric surgeon.

Gastroschisis is considered a surgical emergency and should be corrected as soon as possible. In the surgical management of these defects, the infant is stabilized either by fascial or skin closure or with construction of a prosthetic sac (called a “silo”) enclosing the herniated viscera (5). Small omphaloceles (5 cm or less) usually can be closed primarily. Larger defects are repaired either by closing skin but leaving a vertical hernia that can be repaired later or by constructing a silo that is compressed on a daily basis. When the contents of the site are completely reduced into the abdomen (usually in 7 to 10 days), fascial closure is possible (5).

Complications

Despite the measures already described, the infant may arrive at the accepting hospital with problems related to hypothermia, volume depletion, acidosis, or all three (2). Insensible fluid loss is minimized by the overlying plastic wrap but must be watched closely to avoid drying of the viscera or hypovolemia in the patient. Excessive handling of the bowel may predispose to infection or injury.

Bladder Exstrophy

Exstrophy of the bladder occurs in 1 per 10,000 to 1 per 50,000 live births and results from incomplete fusion of the caudal fold, abnormal development of the cloacal membrane, and failure of anterior closure of the pelvis at the symphysis pubis (4) (Fig. 39.1C). Classic exstrophy of the bladder, with the bladder open on the lower abdominal wall, is usually associated with some degree of epispadias of the male or female genitalia. The ureteral orifices are usually plainly visible, with a continuous dribble of urine covering the exposed bladder (7). At birth, the bladder mucosa is thin and smooth, but with exposure it becomes hyperemic, thickened, and friable (2). The kidneys and ureters are usually normal at birth but may become secondarily dilated by reflux and infection or by fibrosis of the ureteral openings.

Procedure

The bladder should be covered by plastic film wrap such as Saran or Glad or by Vaseline gauze (4). Antibiotics are not necessary. The infant should be transferred to a neonatal unit for further evaluation. Repair is done electively in stages, beginning in the neonatal period with the ultimate goal of closing the bladder, reconstructing the abdominal wall, genital reconstruction, and eventual urinary continence.

Cloacal Exstrophy

Cloacal exstrophy or vesicointestinal fissure is a complex abnormality consisting of a large omphalocele beneath which lies the open bladder. The bladder is divided in half by a zone of intestine, with an upper orifice leading to the terminal ileum and a lower orifice leading to a short colon (5 cm) that ends blindly (2,7). Almost all infants with this defect have either a meningomyelocele or a tethered cord (2,7). Other

associated anomalies include undescended or absent testes, bicornate uterus, and absent or duplicated vagina and epispadias. In addition, 50% of infants have abnormalities of the kidneys or ureters (2). Cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, diaphragmatic, and other small intestinal abnormalities may occur (2).

associated anomalies include undescended or absent testes, bicornate uterus, and absent or duplicated vagina and epispadias. In addition, 50% of infants have abnormalities of the kidneys or ureters (2). Cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, diaphragmatic, and other small intestinal abnormalities may occur (2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree