Emergency Evaluation and Treatment of the Sexual Assault Victim

James L. Jones

Sexual assault or rape is a common violent crime in the United States. According to the National Crime Victimization Survey, there were 260,940 rapes and sexual assaults in the United States in 2006 (1).

Accurate statistics are difficult to obtain because sexual assault is a common crime and not often reported to authorities. The Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network statistics for 2001 show that 38.6% of rape was not reported to the police (2). Most rape victims who know their assailant are less likely to report the crime when the perpetrator is an acquaintance. These factors make sexual assault the most underreported crime in the United States.

Since the 1970s, rape crisis centers have been developed in urban areas of the United States to deal with the particular problems of the sexual assault victims. Rape crisis centers often provide training for physicians and nurses in performing sexual assault examinations. These centers also provide continuity of care and counseling that is difficult to obtain in many other settings. The multidisciplinary approach used by many centers underscores the importance of the psychological aspects of sexual assault. In addition to meeting the acute medical needs of the patient, the medical staff is responsible for advocating for the immediate and long-term emotional needs of the victim as well.

Many physicians are uncomfortable performing sexual assault examinations. Sexual assault examinations are performed by nurse examiners in many states (3,4). The most important considerations in determining who should perform a sexual assault examination are experience and interest, as well as local statutes related to medical care. The forensic aspects of the examination require strict attention to detail and experience in performing sexual assault examinations. The psychological aspects of sexual assault demand that the examiner be compassionate, patient, and understanding. A list of the responsibilities of the examiner in caring for a victim, as described by Kobernick et al. (5), follows:

1. Prompt treatment of physical injuries

2. Collection of legal evidence

3. Careful physical examination

4. Documentation of pertinent history

5. Prevention of pregnancy

6. Prevention of sexually transmitted disease

7. Psychological support and arrangement for follow-up counseling

The physician or examiner should be familiar with all these aspects of care of sexual assault victims.

Five to ten percent of adult sexual assault victims are men. It is important to realize that male victims deserve the same respect and treatment considerations as female victims.

TRIAGE

Upon arrival at the emergency department, the victim should not wait in a public area but should be quickly and discreetly escorted to a private examination area. An assessment of the extent of the victim’s injuries should be made on admission. Critically injured victims should be treated without delay in an urgent care area. The forensic examination should be performed only after the victim is stabilized. If the victim has to be taken to the operating room, specimens can often be safely collected during an operative procedure. Fortunately, sexual assault victims are not usually severely injured. An unpublished review of 100 consecutive assaults reported to the Sexual Assault Recovery Center at Shands Hospital, Jacksonville, Florida, found that only two patients required hospitalization for injuries sustained during an assault. One patient was bleeding heavily from a labial laceration and required an examination under anesthesia; the other was a victim of a severe beating. A study by Hicks of rape victims presenting to a Miami emergency room also found that <1% of all victims require hospitalization (6).

The victim should be instructed not to wash, use the toilet, eat, or drink until the examination is completed. If friends or family members are present, they may remain with the victim if she wishes. If the victim is alone, a nurse or rape crisis counselor should stay with her. The victim should not be left alone.

Loss of control is an important psychological factor in rape; it is important to help the victim reestablish control over her surroundings. It is important that the victim be reassured as to her safety. The examiner should carefully explain the procedures that will be performed. At the Sexual Assault Recovery Center at Shands Hospital, the victim is given a folder containing information about each step of the examination. A list of tests that have been ordered is included along with the expected completion date. The victim should be informed that she may refuse any part of the examination. Consents for the examination and the release of the information to the police should be reviewed carefully and signed. Whether the victim intends to report the crime should be immaterial; she is still entitled to medical care.

FORENSIC MEDICINE

Many physicians find the medicolegal aspects of sexual assault intimidating. The examining physician must be familiar with the specific guidelines issued by the prosecuting attorney for sexual assault examination (7). Prepackaged rape kits are also available that should fulfill a particular state’s guidelines for collecting evidence. Common medical practices, such as using the newer rapid DNA probe technologies for detection of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis, may not be admissible in some courts and cannot replace a traditional culture in making a diagnosis. As newer technologies are introduced, state guidelines change, and the hospital’s protocol should be updated.

The most important aspect of a forensic examination is adequate and careful documentation. Notes must be legible. Physicians may be called to testify years after the assault, and they must be able to rely solely on notes taken during the examination. It is equally important that physicians not make remarks that may be misinterpreted at a later date or in court. This can be avoided if physicians realize that their role is not to determine whether the victim has been raped but to determine whether the examination is consistent with sexual assault. Physicians should avoid conclusive statements that are not supported by facts or their experience. Remarks concerning the victim’s behavior should not be entered into the record unless they are purely descriptive. Coping mechanisms produce a wide spectrum of responses to rape, thus physicians may encounter behavior that seems

incongruent with a history of assault. Therefore, statements such as the victim’s behavior is inconsistent with sexual assault are inappropriate. The patient’s affect can be described instead.

incongruent with a history of assault. Therefore, statements such as the victim’s behavior is inconsistent with sexual assault are inappropriate. The patient’s affect can be described instead.

Physicians should also understand the concept of “chain of custody.” Courts will not consider evidence admissible if a direct line of custody cannot be established between the examiner and the court. As the evidence is gathered, it is placed into separate envelopes, sealed, and initialed. All specimens must be clearly labeled with the victim’s name, the date, the examiner’s name, and the source of the specimen. Clothing is placed in paper bags. Glass slides should be placed in carriers with rigid sides. The bags, envelopes, and carriers should be sealed with plastic tape and the examiner’s initials written across the tape or the seal. This should be done in such a fashion that if the container were opened, the tampering would be obvious. The evidence should then be placed in a large paper bag or envelope and sealed. The evidence is then either handed directly to a police officer or placed in a locked cabinet. A receipt should be obtained for the evidence when it is transferred to the police. Breaking the chain of custody, by faulty handling or record keeping, may make the entire examination inadmissible in court.

OBTAINING A MEDICAL HISTORY

The purpose of obtaining a history in a sexual assault case is to record as soon as possible the events that have occurred and to guide the physician during the examination. If the patient is an adult and a good historian, the physician may eliminate some parts of the exam and tests, such as obtaining rectal or oral cultures when only vaginal penetration has occurred. In the absence of an adequate history, the physician should perform an encompassing physical examination. If the physician records remarks made directly by the victim, these should be placed in quotations; otherwise, the remarks are assumed to be paraphrased.

The history should include the following:

1. Medical and surgical history: This should include allergies and medications.

2. Gynecologic history: The examiner should emphasize last coitus, menstrual history, current method of contraception, history of sexually transmitted disease, history of pelvic inflammatory disease, tampon use, and douching practices.

3. Obstetric history: Methods of delivery, gravidity, and parity.

4. Location, date, and time of assault.

5. Description of assault: The victim should be asked to describe the assault in her own words. The examiner should ask the victim to include the number of assailants, whether force was used, the presence of weapons, and what type of assault occurred. If the patient does not volunteer enough information, it is appropriate to ask, for example, “Did he put his penis in your vagina?”

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION OF THE ADULT

It is particularly important to inform the patient again of exactly what the examination involves and to reassure her that the examination will not be painful. The examiner should collect as much of the victim’s clothing as feasible, particularly the panties. The victim should remove the clothing herself, preferably over a clean paper or cloth sheet to catch any debris. If it is necessary to cut the victim’s clothing to remove it, torn or stained areas should be left intact.

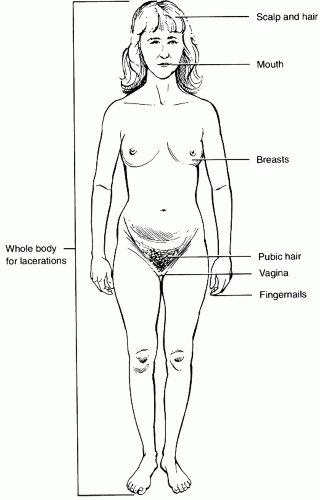

The victim should then be carefully examined, paying close attention to lacerations, bruises, and foreign material (Fig. 26.1). Any foreign material should be carefully removed, placed in an envelope, and identified as to the location of origin. Bruises, bite marks, and lacerations should be carefully described and diagrammed. Lacerations should be inspected carefully, particularly if a sharp object was used in the assault, to rule out a deep, penetrating injury. Photographs may be helpful if they effectively demonstrate an injury but should be taken by a

police or a medical photographer. Photographs can actually harm a case if they do not add significant graphic detail. The photograph should be labeled with an indelible marker or by other permanent means of identification.

police or a medical photographer. Photographs can actually harm a case if they do not add significant graphic detail. The photograph should be labeled with an indelible marker or by other permanent means of identification.

A tongue blade or a moist, cotton-tipped applicator should be used to collect any suspicious stains or deposits on the skin. Since semen fluoresces a bright yellow-green, deposits can often be identified with a Woods light. The head hair should be combed with a new comb over a paper towel, carefully collecting foreign material. Loose pubic hair should be collected in a similar fashion.

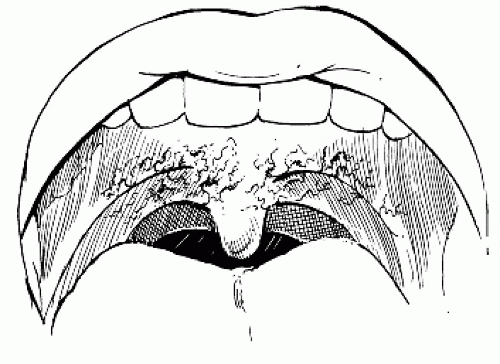

The oral cavity should be carefully examined with a tongue blade. Victims will often bite themselves during a sexual assault, producing small abrasions in the buccal mucosa. Fellatio may also cause small submucosal hemorrhages, which are usually seen at the junction of the hard and the soft palates (Fig. 26.2) (8). If there is a history of fellatio, the oral cavity, especially the areas between the gum and the lips, should be swabbed with a cotton-tipped applicator and glass slides should be prepared. When obtaining specimens for determination of the presence of sperm, two slides should be made. One goes directly to the forensic laboratory; the other is used immediately as a wet mount. The specimens should be made with several swabs. After the slides are prepared, the swabs are allowed to air-dry before placing them in an envelope. The presence of sperm as noted by the examiner should be recorded in the chart, and a separate notation should be made as to whether the sperm are motile. Pharyngeal cultures should be taken for N. gonorrhoeae. A saliva specimen is obtained from the victim for blood antigen determination. A small square of filter paper is placed in the victim’s mouth, and the victim is encouraged to saturate it with saliva. It is important that no one handles the filter paper except the victim. If there is a history of fellatio, the victim should rinse her mouth out with water and wait 5 minutes before preparing the specimen.

The fingernails should be inspected for foreign material under the nails. If any foreign material is present, including dirt, it should be collected over a paper towel with a blunt wooden probe. Scrapings from each hand should be submitted separately.

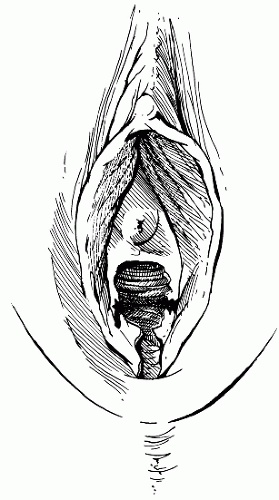

The victim is then asked to lie on the examination table in the dorsal lithotomy position, so that a pelvic examination can be performed. The labia, posterior fourchette, and vestibule are carefully inspected under adequate lighting. Bruises, lacerations, and tender areas are carefully explored, diagrammed, and photographed, if necessary. Wood’s light should again be employed to highlight semen deposits. In younger victims, the posterior fourchette is very susceptible to injury, which appears as fine lacerations. In cases of chronic sexual abuse, the examiner should look for scarring in the posterior fourchette and the posterior vestibule.

Physical findings suggestive of vaginal penetration are present in approximately 50% of sexual assault victims, but only 2% show clinical evidence of significant genital trauma (9). Injuries are typically minor and appear as small abrasions and lacerations. The examiner should describe any visible lesions and diagram their locations. The most commonly injured sites are the posterior aspect of the introitus, the hymen, labia minora, and the posterior fourchette (Fig. 26.3) (8). In a study of 311 rape victims by Slaughter et al. (10), 76% of the victims had an average of 3.1 sites of injury. Victims with nongenital injury are more likely to have genital trauma. In the absence of gross laceration, two techniques can be employed to highlight microlacerations: colposcopy and toluidine blue staining. The colposcope is a medium-powered binocular microscope with an internal light source that is commonly used to visualize the cervix (9). In a study of 18 volunteers examined within 6 hours after coitus, Norvell et al. (11) showed that microlacerations of the introitus and the vagina could be identified in 61%. Toluidine blue staining can also be used in the absence of gross lesions to highlight microlacerations (12). The stain should be applied directly to the perineum and then carefully wiped off using lubrication jelly on a gauze. Toluidine blue is a nuclear stain, so normal keratinized skin will not stain. Microlacerations show up as finely stained blue lines.

The buttocks are then gently separated and the anus is inspected for evidence of small fissures, lacerations, and scarring. Hemoccult should be obtained for evidence of occult rectal bleeding. If there is a history of anal penetration, the

physician should look for evidence of rectal bleeding. Unexplained rectal bleeding should alert the physician to the possibility of bowel perforation. Proctoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy is then indicated.

physician should look for evidence of rectal bleeding. Unexplained rectal bleeding should alert the physician to the possibility of bowel perforation. Proctoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy is then indicated.

Anal swabs should be taken and glass slides prepared. Sperm may be recovered from the rectum, but the yield is usually significantly lower than that from the vagina or the cervix (13).

A speculum moistened with warm water (do not use lubricant) can then be gently inserted in the vagina. The cervix is visualized for any evidence of trauma. Microlacerations on the cervix resulting from sexual trauma can be visualized with the aid of the colposcope (9). A specimen should be taken from the external os, and two glass slides should be prepared. Samples are also taken from the vaginal pool. Whether the sperm are motile should be noted. Sperm may remain motile in the vaginal pool for 12 hours. Sperm survival in the cervical os is considerably longer; motile sperm can be recovered from the cervix for up to 7 days (14). Cultures for gonorrhea and Chlamydia should be taken. As noted earlier, most courts will not accept direct antigen tests for determination of gonorrhea. At Shands Hospital in Jacksonville, Florida, the sensitivity and the specificity of the BD Probe Tec (15) assay are 100% and 100% for both N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis.

Two vaginal swabs are obtained for antigen determination. Blood group antigens are secreted into body fluids by approximately 80% of the population (16). Although it cannot identify a specific assailant, this technique is useful to exclude or include someone from a list of suspects.

Vaginal swabs are also obtained for analysis of the prostatic antigen, p30, and acid phosphatase. Finding these seminal factors can establish penile penetration in the absence of sperm.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree